A heathen is born.

A heathen is made.

Both statements can be true.

It’s 1970.

Sides were fluid, dissociating from old sides, not so long ago; sides, a long way off before sides got back into formation. Unmovable sides. Static sides; sides as opposed to side-by-side.

It’s 1970.

A thirty-two-year-old woman from Elizabeth, New Jersey wrote a book about sides.

Born to a Christian mother and a Jewish father, Margaret Simon (Abby Ryder Fortson) is being raised in a godless household.

It wasn’t a difficult choice for the parental unit, not after both of their families reacted with antipathy towards the very idea of an interfaith marriage.

By default, Grandma Simon (Kathy Bates) comes around to accepting the former Barbara Hutchins (Rachel McAdams) as her daughter-in-law, one suspects due to common geography, then does so unconditionally after Margaret is born.

On the other hand, Paul and Mary Hutchins (Gary Houston and Mia Dillon), headstrong and devout, never gave Herb (Benny Safdie) a chance to prove himself, choosing instead to put an indefinite pause on familial ties with Barbara, a stranger of their own making, this transplanted New Yorker with her exotic husband and half-breed daughter.

It’s 2023. Both statements can be true.

- A heathen can be good.

- A heathen is going straight to Hell.

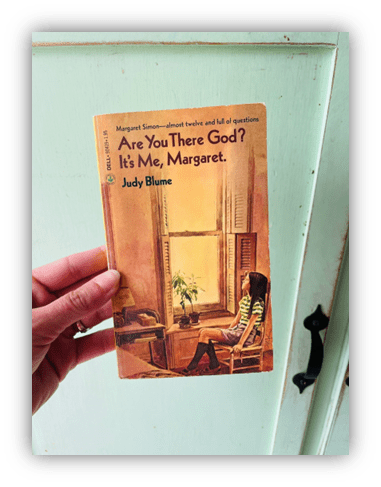

It’s a hot button issue, religion. Understanding the potentiality for national boycotts and spur of the moment walkouts, Kelly Fremont Craig (The Edge Of Seventeen) took on the daunting task of adapting the Judy Blume young adult novel Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret. As a screenwriter, Craig adds a NYC sequence that doesn’t exist in the original text, which starts with the family already having made the move to the suburbs of New Jersey.

Blume writes, “my grandma is too much of an influence on me,” or in other words, Barbara is afraid that Sylvia will undermine the couple’s plan of staggered obsolescence in regard to formalized religion and convert Margaret.

Since Barbara’s parents come across as antagonists, the filmmaker employs an equal and opposite strategy, in which the estrangement of their daughter gets counterbalanced by a pointed visual, the Simons’ cluttered and crowded NYC apartment, a metaphor for Sylvia, who wants a temple companion, a surrogate for her worldly son. The claustrophobic apartment, the closeness of their bodies, both suggest that Margaret isn’t being given enough breathing room to decide on her faith in an organic manner.

A heathen is curious.

A heathen goes on the church circuit.

A heathen talks to god, but which god? Which god knows all about her new friends, the boy she has a crush on, her growing bra, and speculative menstruation?

Are You There God, It’s Me, Margaret? is a period piece; a period piece in italics facilitated by colorblind casting, a relatively recent filmic norm employed, perhaps, most notably in the last trilogy of Star Wars movies.

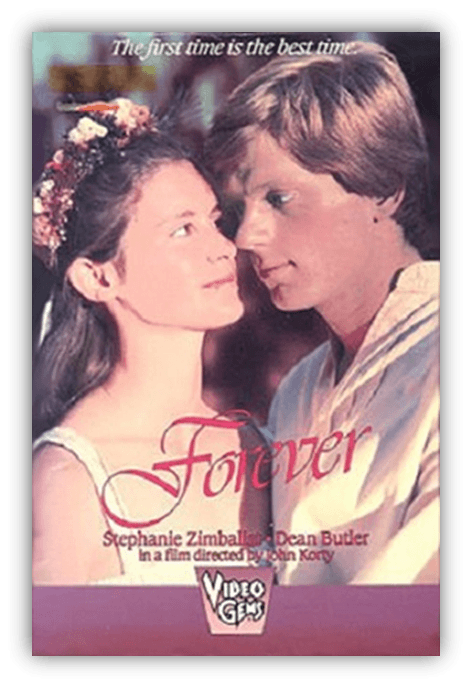

Compared to another Judy Blume adaptation, John Korty’s Forever, a 1978 made-for-television movie starring Stephanie Zimbalist, the racial heterogeneity can’t help but look like an anachronism.

A Garden State that exists in synchronous time, an intertwining past and present, a temporal distance magnified by historical rhyming, which puts the onus on the viewer to arbitrate our changing social and political mores.

A second binary: black/white, attenuates the original literary binary: Christian/Jewish, so the assignation of perceived hubris doesn’t fall solely on the shoulders of one theological subset.

“You’re born into it,” insists Paul.

Religious instruction should be determined by mom and dad.

The hippies beg to differ.

Are You There God, It’s Me, Margaret? deviates from the author’s vision of religious autonomy, when the girl, Judy Blume aficionados will note, sides intertextually with Barbara’s father by making it known to her progressive parents that she’d be happier had they decided for her: the church to attend, the god to worship. Blume never takes into account that agnosticism leaves Margaret feeling adrift. She’s an only child with no pet, after all. “God” is her imaginary friend; she wants a corporeal god, a higher power so that her latent faith can be born and seek purchase in the pews.

Margaret gets her period. Margaret is a “woman” now.

Margaret’s prayer is answered.

Barbara takes her leave from the bathroom, allowing Margaret to savor this moment on the throne alone. Seconds pass; a thought is formed and finalized, as indicated by her focused eyes on the heavens. What religion Margaret chooses depends on who you are; the god on the other side of your conversation.

But maybe the penultimate scene, a party to celebrate the end of grammar school rectifies the ambiguity.

The parallel timelines conjoin, arguably, because the adaptation climaxes with a different clash. In the book, Margaret has a falling out with Moose.

The girls’ friendship has a chance of survival in junior high, since race and religion mattered less than it does so now. In the film, we can see that her friendship with Nancy Wheeler (Elle Graham) won’t last the summer. Margaret chooses Laura Denker (Isol Young). The graduating sixth grader displays a maturity beyond her years. She asks the lonely girl, ostracized for being tall and prematurely developed, to dance. Sides are being drawn. Nancy and Gretchen Potter (Katherine Kupferer) remain on the sidelines. But Jamie Loomis (Amari Alexis Price) joins Margaret and Laura. The Preteen Sensations are no more.

Junior high in 1970.

Junior high in 2023.

It doesn’t have to be a war.

It doesn’t.

Great piece, Cappie. I’ve never read the book, though I heard a lot about it growing up, so this is likely to encourage my seeing the movie (and maybe pick up the book).

Thoughtful commentary, Cappie. There is a lot to unpack here and with the film itself. I did not read the book, but I read a few other Blume books as a child and they were basically canon in my young life. I told my 13 year old daughter we were seeing the movie, plain and simple and surprisingly, she didn’t object. I loved it and she said she liked it, even though she was a little past the age of the protagonist. I appreciate your angle on the religious aspect as an umbrella theme of what is happening in this girl’s life all at once. You gave me a lot to think about.

Got to admit that I’ve never read any Judy Blume. My sister is three years older than me and read them all at around a similar age to what my daughter is now. Three years behind her, my mind only worked in linear fashion. If my sister was reading a book that meant it was for girls so there was no need for me to investigate further.

I’ve seen a lot of positive reaction to the film and your piece just adds to my interest in rectifying the mistakes of my younger self. One to suggest to my daughter on weekend movie nights. Thanks Cappie.

Judy Blume is an author for young girls

Yes. Absolutely….except when she isn’t. The girl I had a crush on in fifth grade got the book Forever, and she read it to us during recess, and shared it when she wasn’t reading it herself. It was…good, at least when Pam read (she could’ve probably spotted the hearts in my eyes).

My daughter and wife read this book recently, since she’s 10 and some of her friends are going thru changes. I never had anyone to talk to about these changes, so the book/movie/my wife are great in assisting with understanding what’s happening.

They loved the book, AND the movie – so much so they saw it twice. A great write-up, even for someone who hasn’t indulged in Blume in 44 years…

I definitely plan to see the movie — most anything with Rachel McAdams where she gets some agency (e.g. Game Night, Spotlight, Eurovision) is a worthwhile view. Plus the reviews have been great. It’s on my list.

Of course this has always been true. It’s not about being good, it’s about having faith.

Interesting to have this follow up rollerboogie’s piece last week. One line you said really stood out to me –

“Religious instruction should be determined by mom and dad.

The hippies beg to differ.”

My goodness, that summed up my childhood to a T. Mom’s mom was Lutheran; mom’s dad was Catholic. Dad’s folks were Methodist. I was baptized Lutheran. But they rarely went to church when I was a kid, and we didn’t belong to any. Instead, I had this book series of Bible Stories geared towards young kids, and my dad would read from that to me as a kind of homeschooling Sunday School.

Never considered it until years later how radically different that approach was from other people (my parents were total hippies, 100%), but yeah, it certainly made for a much more holistic (no pun intended) outlook towards all religions. And seeing how detrimental forcing kids on one path and one path only (MrDutch’s family we’ve come to realize were in a legit cult, and it really messed up a lot of the kids in that church, not just him) can be, I do appreciate that I never traveled that path.