How did Israel transform from a polytheistic society into a monotheistic one?

We covered some of the broader details last time:

A band of refugees was adopted by the Canaanites as fellow tribesmen and priests. This was the tribe of Levi, and they worshipped a God they called Yahweh.

Yahweh resembled the Canaanite king-of-gods El, and so the two cultures united around the worship of El and Yahweh as the same deity.

But despite a shared love of one High God and some sacred origin myths to forge a common identity, the worship of other regional gods such as Ba’al and Asherah persisted for centuries, as archeological and biblical evidence both demonstrate.

So what were the factors that helped the Levites to complete the cultural transition from many gods in Israel to one?

Cutting the Bull

One important factor was the power of narrative. Through the sacred historical narratives, the Levites were able to actively shape cultural awareness and practice. We already saw such storytelling power with respect to the birth of the 12 tribes of Israel, the escape of all of the tribes from Egypt, and the Israelites’ fabled battle of Jericho to emerge “victorious” of the pagan Canaanites.

These were largely fictions created to unite disparate cultures into one common identity, though the stories hold nuggets of truth in them as well.

So with the rival deities. When mentioned in the Bible as we have it now, the depictions of Ba’al and Asherah tend to be as false idols worshipped by foolish Israelites who are tempted by neighboring pagan cultures such as the Edomites. The truth is that monotheism in Israel was very much the exception rather than the rule for many centuries.

But the Levites had power and influence over religious matters, especially once their sacred stories were written down to cement their authoritative power, and to prevent the distortion that comes from the oral transmission of stories. Through their stories, the importance of Yahweh was built up, while the power of the other gods was played down.

Red Flags

Another factor was the political turmoil that befell the people, often creating new tensions, new calls for unity, and new stories.

The great kingdom of David and Solomon soon split into northern and southern kingdoms, and these factions began to tell their own particular variations of the sacred origin stories of Israel. Yet once the northern kingdom was destroyed by Assyria, the survivors fled to the south for refuge.

This reunion soon presented the people with a troubling predicament:

The sacred origin stories now had rival versions with incompatible details!

As support for their claims, both northern and southern factions could point to their own written scriptures as the authority.

The solution to this predicament was the wholesale combination of both scriptures into one master document.

This version omitted none of the details, thus preventing protest along the lines of: “The true word of God surely would mention when Moses did X in the desert!”

The compromise was that some details that various factions found insulting were also included.

Thus there are scenes written by a northern Levite that depict the high priest Aaron (whose descendants hailed from the south, in Jerusalem) as being wayward and foolish. And yet this controversial content remained and sat next to passages that praise Aaron. It was one unhappily inclusive master narrative to unite the people.

But later on, more scriptures emerged to lay claim as the true sacred story of the people.

One of these was written during the time of King Hezekiah, a leader who sought to bring dramatic religious reforms to his kingdom, including the strict worship of Yahweh alone. The priest who wrote the scripture was an Aaronid priest, and he wrote passages that marred the reputation of Moses to “correct” the earlier scripture that had insulted Aaron. He also depicted God as an all-powerful cosmic entity as opposed to the humanistic depictions of Yahweh in the earlier scriptures. This was the only God to worship; everything else was empty idolatry.

Another set of scriptures came later, during the reign of King Josiah, who attempted to enact the reforms that Hezekiah could not.

The scribe Baruch ben Neriah, in consultation with the prophet Jeremiah, produced an authoritative sacred testimony of the people to support these reforms.

Later, once Josiah was cut down by Babylonian forces and his line extinguished, Baruch ben Neriah and Jeremiah revised their sacred works to explain why God would strike down his chosen people and lead them into exile. The main answer: because of the people’s worship of pagan idols.

Torah! Torah! Torah!

After the king of Persia freed the Israelites from exile in Babylon, he allowed them to return to the land of Judah and rebuild their temple.

Going forward, there would be no more king to unite the tribes, only the priestly temple authorities, and so the need to unite the people into a coherent movement would be greater than ever.

The priest and scribe Ezra was one figure chosen by the Persian king to lead the people back to Judah and re-establish their society.

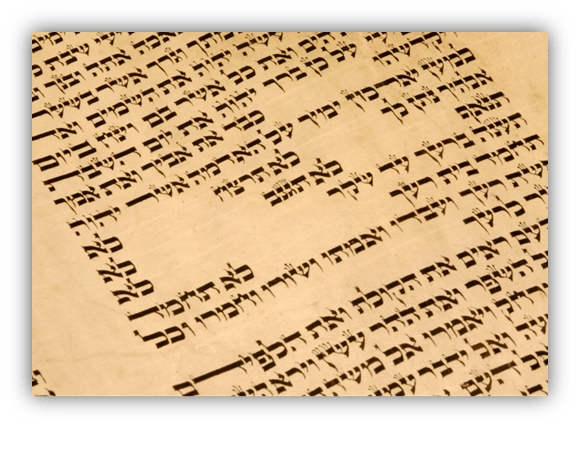

Once the great Jerusalem temple was rebuilt, Ezra stood among the people and produced for them a miraculous document: the true Torah of Moses, the complete and unequivocal word of God with respect to their origins, and how they must live their lives.

In fact, Ezra had combined all of the older scriptural sources into one omnibus master document:

the northern and southern ancient works, the priestly document from Hezekiah’s reign, and Baruch’s writing from the end of Josiah’s reign to the exile.

Yet this wasn’t the mere appending of the stories back-to-back-to-back: this was an elaborate interlaying and interweaving of the different texts into one flowing story.

There are in fact many redundancies, contradictions, tonal shifts, reciprocal insults, and other quirks that can be observed upon close inspection, which belie the Torah’s patchwork history and composite design.

But so intricate was Ezra’s cutting and weaving that no priests, laypersons, or scholars noticed such narrative quirks until more than two thousand years later! That is an astounding accomplishment.

Importantly, the final Torah also likely featured redactions of material that Ezra found to be unwelcome or unnecessary for the authoritative word of God. One tantalizing possibility is that the earliest scriptures (the northern and southern rival versions) had more explicit content detailing the actual death of the old Canaanite gods at the hands of Yahweh. There are stray verses in the scriptures we have today that seem to allude to the gods meeting Yahweh’s fierce judgment. It may be that Ezra removed most of the details of this judgment, and left only vague hints.

If this is the case, then it speaks to the power of silence in a narrative.

While written satires and polemics can be devastating for the reputations of their targets, the sharpest knife in this fight may have been the subtlest one: simple omission from the record.

Had his remains not been so unceremoniously discarded, perhaps Ankenaten would have smiled from his grave.

Whatever the specific details may have been, the forging of this final Torah—which was itself the product of much toil, discord, and compromise—this lovingly crafted patchwork tapestry of sacred history did much to erase those pesky pagan gods from Jewish culture, and unite the people together under one God.

During the Second Temple period, monotheism finally reigned supreme.

…to be continued…

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” upvote!

As lovethisconcept indicated last time, almost none of these conclusions are definitively settled among scholars. Jeremiah is widely accepted as a principal influence on the book of Deuteronomy, as that book shares so much in common with Jeremiah and Lamentations. Baruch ben Neriyah being the author of Deuteronomy is Richard Friedman Harris’ well reasoned conjecture.

There also is some debate as to when the “Priestly” scripture was written. Some scholars date it as the latest component, written during or after the Babylonian exile. Yet I haven’t encountered an argument for a later dating that directly addresses Harris’ connections of the content to the court of King Hezekiah.

But sometimes you have to ignore all the fancy sidesteps and just CHARGE! toward the gist of a narrative.

It’s fascinating to learn how much old school cut and pasting was going on to reach an ‘official’ Torah. First thing that came to mind was a history of the Civil War that might have been culled together from Atlanta scholars in 1870 and some Ivy League professors from that time, mixed in with a West Point historian’s perspective, considering how Robert E Lee was such a standout graduate from there.

(Side note – I’ve always felt Lee’s reputation has been screwed over horribly. If his family had lived on the eastern banks of the Potomac instead of a hillside plantation overlooking the Potomac and DC, the man would probably be as revered as George Washington in American lore. Instead, he’s made a pariah because he happened to be the best military General that was born in a Southern State and more or less got the role he did by default. I know nothing of the actual truth of course, but I have just always gotten that vibe.)

It’s like when I visited the Norfolk Navy Base in Virginia when I was 17 or so. I’m reading things in the museum about Civil War navy battles and the narrative was so weird. It took me a few minutes to realize that was because I’d been forced all my life to see the Civil War from the north’s perspective, and here was my first exposure to a Southern viewpoint of the war (I feel like I’ve mentioned this before…). Anyway, made me angry to realize how easily I’d been manipulated in learning that history.

Having an all-encompassing version of the Torah was a pretty smart way to go, IMO.

Thanks for today’s brain food, Phylum!

Yeah, certainly the rival narratives of the Northern and Southern kingdoms can get you thinking about a different North and South and their rival narratives.

Here in Alexandria, the tour guides tend to treat Robert E Lee with a fair amount of nuance. There is plenty of weaselly Confederate revisionism out there that sickens me, but at the same time I don’t think the Northern states were full of good people and the South full of evil people.

I think the structural incentives were completely different, and the Northern states likely would have resembled the South if their livelihoods were similarly dependent upon cotton and tobacco plantations. Even George Washington, who vowed to emancipate all of his slaves, was only able to do so toward the end of his life. And Jefferson, despite seeing slavery as an evil, was never able to do so.

It’s very easy to judge people from a distance and assume you would have gotten it right in the same circumstances. Easy, and almost always misguided.

That’s just the story they tell themselves, if you get my drift…🤓

On the other hand, it’s been my experience, until very recently, that the ‘Lost Cause’ version of events has been a major part of the story of the Civil War. Lee’s been held up as a paragon of gentlemanliness and knightly soldiering for many decades; the reality (as it’s being understood today) is more complicated and (as PofA notes) nuanced. It was treason, though.

People complain about media manipulation but this just shows that it was always so. Borrow a bit from over there, insert favourable interpretation here, omit the inconvenient truth and paste it together as the definitive truth. Same old story just the characters change.

Fascinating stuff as ever.

Yup, ultimately everything boils down to the stories we tell to make sense of our world, to make clear our moral priorities, and to advocate for certain actions or practices.

Ethical standards in journalism can help to get the stories a little closer to objectivity, but that was always a rather WEIRD mutation of the more general trend.

Makes me wonder why anyone believes any origin story.

Except Darth Vader. That one’s definitely true.

You sure about that?

https://comicbook.com/starwars/news/star-wars-darth-vader-anakin-skywalker-father-palpatine/

(OK, maybe that happened outside what we were shown, but is still “true”)

I don’t know much, but DJ Ezra may be the origin of scriptural hip hop…

First of all, thank you for sharing your knowledge, Phylum. This is all new to me.

It should have been obvious, but it never occurred to me that a major religion like Judaism was the result of a sort of colonization, an in country colonization(of the mind), similar to a country imposing their beliefs on another country.

I have a question.

I understand the primary reason for the divide between our two major religions. But does a secondary reason pertain to Moses? He couldn’t have written both the Bible and the Torah.

The Torah (which is the first 5 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Christian Old Testament: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) is traditionally thought to have been written by Moses, but modern scholars don’t think that’s actually the case. The end product we have today is a composite work, likely edited by Ezra. Based on their writing, some of the authors compiled in the Torah scriptures likely claimed descent from Moses’ line (who settled in the North, in Shiloh), while others claimed descent from Aaron’s line (who settled in the South, in Jerusalem).

By two major religions, do you mean Judaism and Christianity? The roots of that divide lie in this Second Temple Period, which is basically what Ezra kick-started with this new Torah in hand.

With no king from the line of David to impose unity in the land of Judea, there eventually emerged an increasing number of factions who broke away from the priests of the rebuilt temple, and formed their own beliefs and rituals. These Jewish sects, perhaps without being aware of it, showcased the influence of foreign occupiers such as Persia and Greek-Macedonian empire of Alexander the Great. These groups are now regarded as “apocalyptic” strains within Judaism, and they eventually included the community who gave us the Dead Sea Scrolls, and later on the earliest Christian communities.

I guess you have to explain this to me like I’m a five-year-old.

So there is overlap between the Torah and the Old Testament?

Now I’m reading very slowly, the transition from paragraph #1 to paragraph #2.

So during the Second Temple Period, did the two religions diverge because in the new edition of the Torah, Ezra made the editorial choice to favor the authors from the Aaron line over the Moses line?

Okay, now reading the last paragraph slowly.

So these Jewish sects…thinking….thinking…thinking…without realizing it, because of the outside influences, shared the same beliefs as the Christians, while still self-identifying as Jewish?

That would make sense. Because during this time, being Jewish wasn’t defined by race? So fluidity between both religions was still possible? I’m using question marks because I never really delved into the study of religion.

Learning is a good thing.

Thank you, Phylum.

This stuff can be quite confusing! And I realize that “Torah” has some flexibility in how it’s used, so it’s important to be clear about how I’m using it.

So there is overlap between the Torah and the Old Testament?

Yup. This week’s post was primarily about the first five books of the Old Testament. Christians call those five books the Pentateuch, and Jews refer to them as the Torah.

So if you get hold of a Hebrew bible, the first five books will be Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, just like the OT of a Christian bible. And this is the Torah, which starts from God’s creation of the world to the Israelites crossing the desert on their way to the promised land.

The content of those five books is what Ezra presented to the people at the new temple in Jerusalem, albeit after heavy integration and editing of older documents to create the version we see today.

So during the Second Temple Period, did the two religions diverge because in the new edition of the Torah, Ezra made the editorial choice to favor the authors from the Aaron line over the Moses line?

I don’t think the divisions were based on anything that was put in or cut from the Torah per se, or at least we don’t know if that happened. But some of the breakaway apocalyptic groups were interested in priestly bloodlines, and this may have reflected why they chose to break away in the first place.

I won’t get into the specifics because it’s all rather thorny, but later on, some groups fiercely disagreed with the practices of the temple priests—for instance, for not fighting against the Greeks forcing worship of Zeus. And to justify their attacks on such practices, they would declare that those priests were not legitimate anyway, since they don’t come from the Zadokites, or some other line that they deem to be the true priestly line. And the heavenly figures they worshipped, who promised to come down and judge the world at the end of days, often happened to sport that specific priestly heritage. Interesting stuff, but rather far from your question about Moses vs Aaron.

So these Jewish sects…thinking….thinking…thinking…without realizing it, because of the outside influences, shared the same beliefs as the Christians, while still self-identifying as Jewish?

I don’t know the exact point when the people started to self-identify as “Jewish,” but it almost certainly came from foreign occupiers such as the Romans referring to them as the people of Judea. That itself is a variation of Judah, the last surviving tribal territory of the ancient Israelites, and the location of the city of Jerusalem, where king David and Solomon once reigned. Judea was the land that the Persian king restored to them, and so from that point on there was the conflation of the land, named after only one tribe, with the entire people of Moses.

And yes, at some point, Moses definitely trumped Aaron in importance for the faith. But given that it was Aaron who was from the tribe of Judah, and whose people settled in Jerusalem, his influence lives on in the name “Judaism” and “Jewish.” Which ain’t a bad legacy!

Back to the Christians, the first Christian communities were exclusively Jewish, albeit of that apocalyptic sort. If you study the community that gave us the Dead Sea Scrolls, there is almost nothing that separates them early Christian beliefs and practices, particularly if you factor in Paul’s description of the early pillars of the movement in Galatians. Both of them were exclusively Jewish, were a separatist community, had similar beliefs about the coming of a son of man to judge the world at the end of days, had ritual washing like baptism, etc. The main difference was that the Christians worshipped a different messiah: a divine figure who was brutalized and sacrificed, while the Qumran/Dead Sea community worshipped an ancient high priest from the time of Abraham, reborn as a heavenly savior. And also that the Christians eventually started to embrace Gentiles as well as Jews, probably from the influence of Paul.

Ah darn it, I meant “from the tribal land of Judah.” Aaron, like Moses, was from the tribe of Levi.

You are a great person, Phylum. Thank you for taking the time to write this.

As always, I have questions…

Can you share any specifics? I love to poke the bear (i.e., my evangelical father-in-law), so I’d love to share these inconsistencies with him.

I’d love some examples here as well 🙂

I was taught (I think in a history class) that Judaism went from a polytheistic religion (one in which YHWH was worshipped as a superior G_D, but recognized the existence of other gods) to a monotheistic one during the Babylonian Captivity. Before then, gods were expected to watch over people in a certain region, but once the people were removed to Babylon and they believed YHWH still “chose” them, he became a more omnipresent one, with no room for Ba’al or any of the others. Is that where Baruch ben Neriah and Jeremiah come in?

Finally, I find it fascinating that the Torah contains no reference to hell/Satan before Cyrus the Great sends them home. Cyrus was Zoroastrian, the religion that believed in a balance between good and evil (and the Gods who ruled each), and a final battle between the two, which became known as Armageddon in the three monotheistic religions.

Examples of composite design.

Collectively, those aforementioned inconsistencies, redundancies, and other quirks form the evidence base for the Documentary Hypothesis of biblical authorship. For an easy-to-read and fascinating tour through that hypothesis, I invite you to check out Who Wrote the Bible? by the scholar I’ve been covering, Richard Elliot Friedman.

But as an example, one instance is found right at the beginning: two creation stories back to back, each with a distinct order of things being created. The first story is much more grand and sophisticated, with God as a cosmic being. The second is much simpler and God is more anthropomorphic in nature. The language used in these versions is also different, for instance with the more sophisticated one using “Elohim” to refer to God for this portion of the story, while the other simply says “Yahweh.”

There are a lot more details to dig into, and Friedman’s breakdown of them is a lot of fun to work through.

Not to mention, Friedman also published a version of the entire Torah with the different sources of each passage made clear. I’d say it would make for a nice gift, but probably not for your father in law!

Examples of judgment against the gods.

Friedman raises the possibility in his book Exodus. It’s primary based on an analysis of the Song of Moses (Deuteronomy 32:1-43). But this one is much more tenuous than the notion of the Torah being composite, so take it with a few grains of salt.

The transition to monotheism

The exact progression from polytheism to monotheism is not fully clear, not least because scholars argue about the dating of the Priestly source of the Torah, the one that starts with the cosmic, omnipresent creator deity. Friedman dates that source well before the exile, while others date it to during or after the exile. If Friedman is correct, then something like proper monotheism was at least being advocated more than 100 years before the exile.

But, regardless of those details, it wasn’t until after the exile that proper monotheism could unite the people, and Ezra’s authoritative take on the Torah was a part of that unification.

No reference to hell/Satan

Yes, the origin of the Dark Lord is a fascinating topic on its own. You are correct in that the preoccupation with a figure of ultimate evil emerged after the Judeans became tributaries to Persia, who spoke of Angra Mainyu, the Zoroastrian precursor to the Devil.

I found this documentary on the topic quite good:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g8XQbqZUkms