The American Revolution of 1776 ignited a cultural firestorm in Western Europe that burned throughout the decades that followed.

By the end of the century, those older societies were somewhat more democratized, much more secularized, strongly nationalized, and of course heavily industrialized.

But what about that first national experiment, the United States of America?

How did its culture fare following its separation from the Kingdom of England?

How did its national identity grow and evolve? And what role, if any, did the trailblazing artists of the time play in this process?

Needless to say, there was nothing quite like the avant garde of Europe in 19th century America.

Life was quite different here.

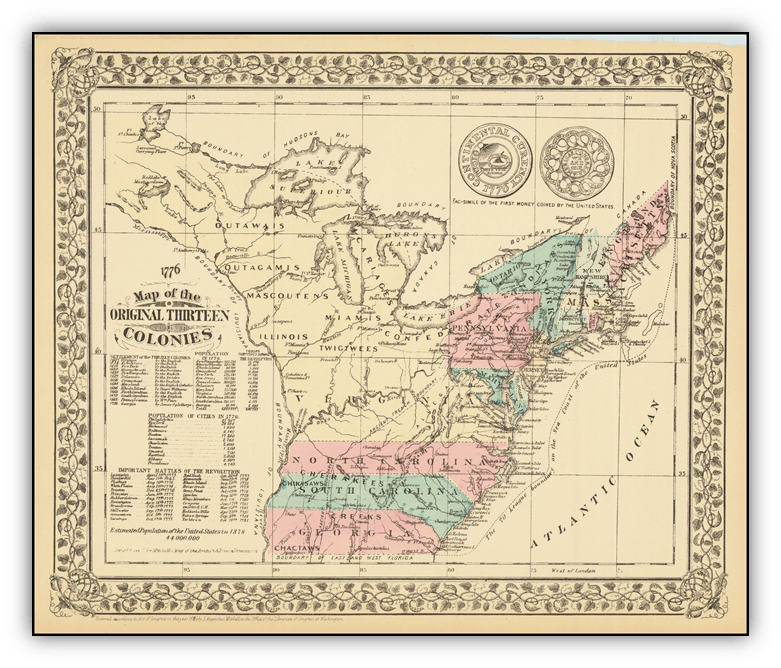

The nation was but a few colonies, recently unified and bent on expansion. Its cities were new and still growing, and rural agrarian life was much more widespread, even amidst the nation’s rapid industrialization.

For a multitude of reasons, art, music, and literature remained rather practical in America, as opposed to shocking or bizarre.

Still, that’s not to say that there weren’t some quasi-bohemian dreamers venturing into new creative spaces.

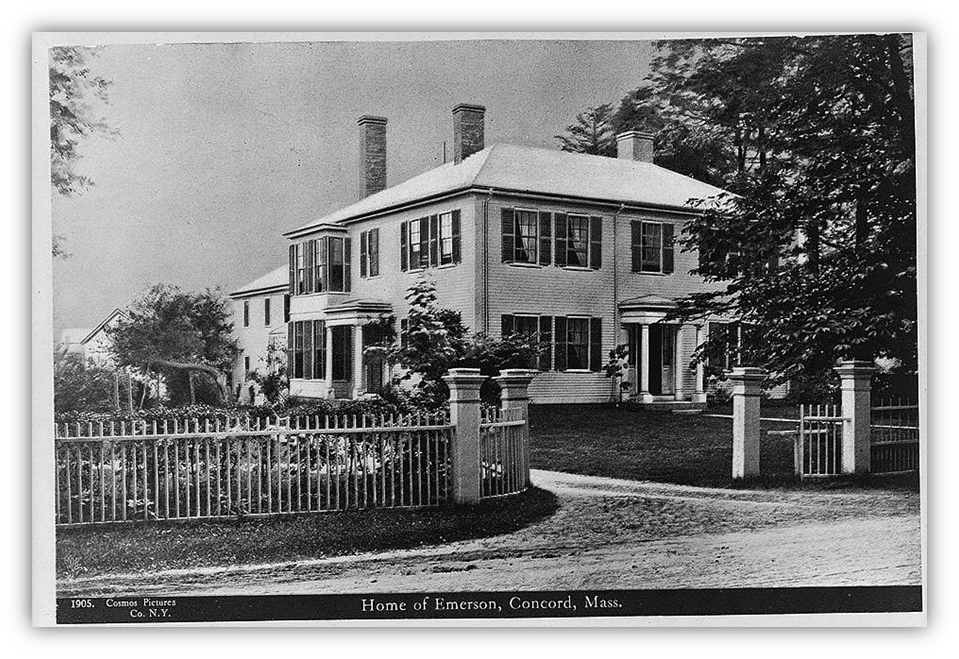

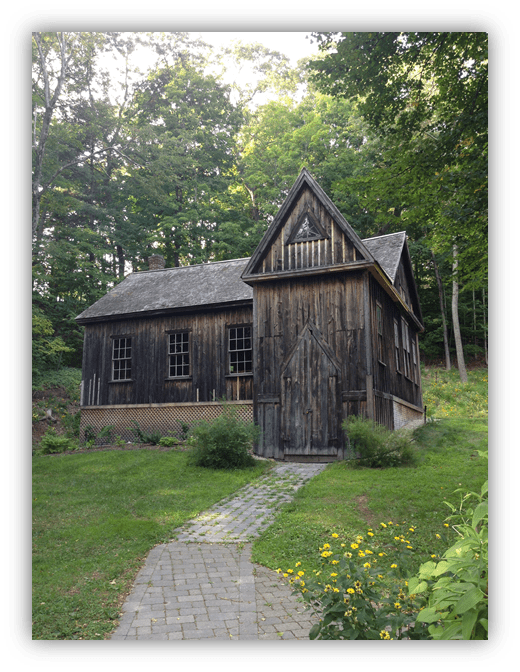

Take, for instance, the transcendentalists of Concord, Massachusetts.

This was perhaps the first major artistic and intellectual movement to emerge in the US.

Like the Romantics of Europe before them, these were writers inspired to exalt intuition, awe, and deep feeling over reason.

They too looked to nature for spiritual healing, as respite from life in the loud and crowded city streets.

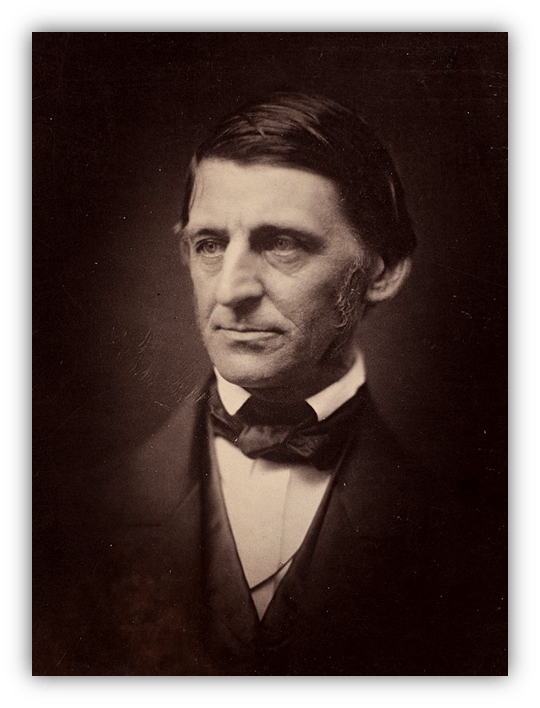

Ralph Waldo Emerson laid down the foundations of transcendentalism in a 1836 essay.

His spirituality as described was thoroughly naturalistic, reflecting what I would call a pantheistic reverence for the world and the living things that inhabit it.

Freedom and nonconformity also play important roles in this outlook.

Indeed, the Transcendentalists like Emerson and Henry David Thorough are most known for their rugged individualism and their solitary retreats into the wilderness. Still, they were not anarchists or proto-libertarians. They saw individualism as one crucial aspect of human nature, but one that must live in concert with the need for collective efforts among others.

“We are amphibious creatures, weaponed for two elements, having two sets of faculties, the particular and the catholic,” Emerson wrote.

Far from serving as a symbol of anti-social separatism, Henry David Thoreau’s account of his year living alone by Walden pond is the perfect metaphor for an amphibious life between civilization and nature, between the self and larger society.

What a difference this was from European Romanticism!

The Transcendentalists weren’t counter-Enlightenment reactionaries; they didn’t seek to escape society altogether, or end society’s modernization.

Instead, they recognized humankind’s sometimes conflicting natures and responsibilities, and sought to find flourishing through balance.

They also didn’t bother with notions of devils and mythic beings in their works; their spiritualism was comparatively grounded, infused by their daily experience of the physical world around them.

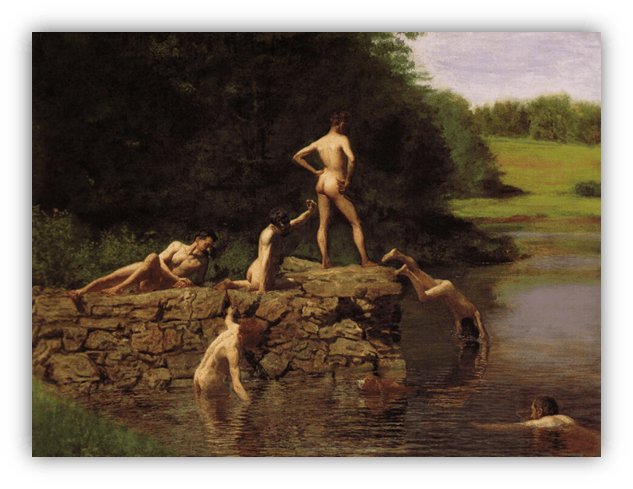

As such, the movement anticipated the French Realist approach of Courbet and his followers. Not surprisingly, Realist painting was taken up by a number of American artists in the late 19th century. Thomas Eakins was perhaps the most important of all, taking Degas’ interest in the human form to new levels of reverent, loving detail, with more than a hint of eroticism.

Eakins, 1885

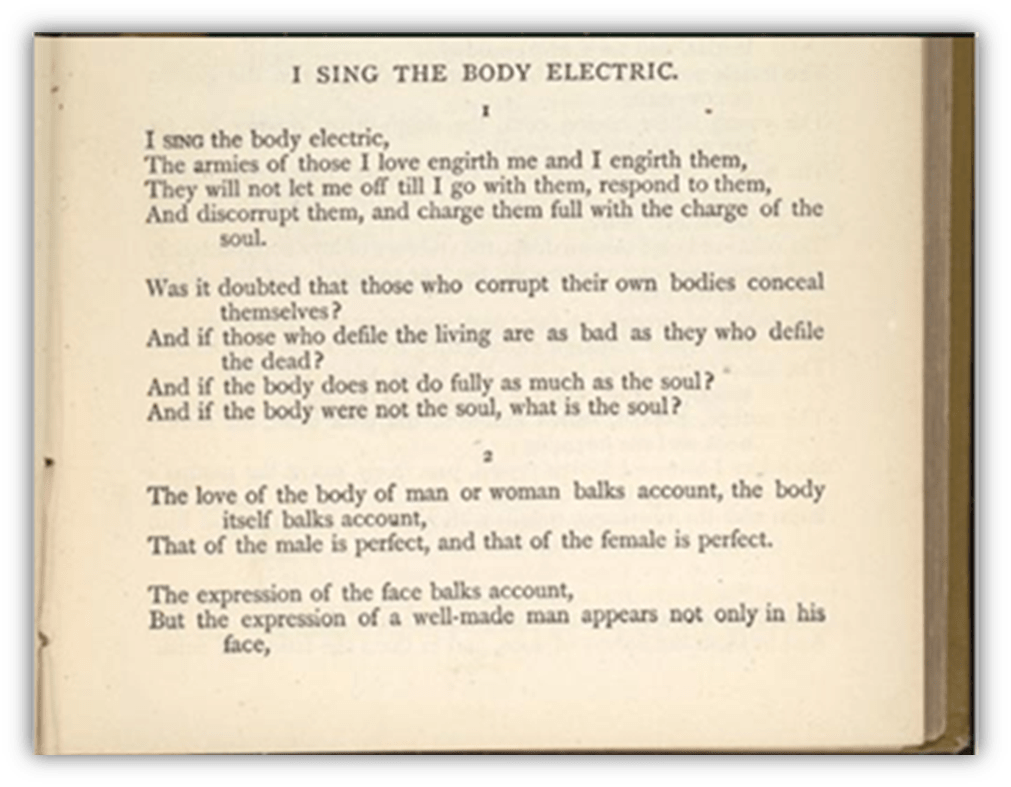

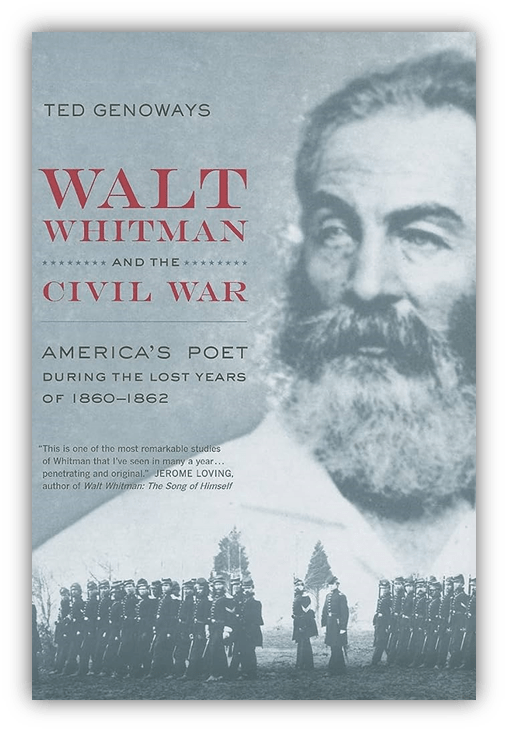

The poet Walt Whitman also had a reverent fixation on bodies, as evidenced in his first works published in 1855.

In Leaves of Grass, Whitman showcased the perfect fusion of Transcendental reverie with Realist impressions of the everyday world around him, including his loves and lusts. For all Charles Baudelaire’s debauchery, he didn’t actually write poems that were erotic. For that, one had to turn to Whitman.

Many of his poems were suffused with the electric charge of physical lust, including homoerotic lust, but also with a love of life, with unbridled optimism, and a deep spiritual connection to everything around him.

The eminent Emerson was one of the first people to praise Whitman’s work, though privately he advised the young poet to tone down the parts with open eroticism to increase chances of public acceptance.

Whitman did publish a collection of selected poems from Leaves, which left out the contentious material. A Whitman sampler if you will, for wider public consumption. But he soon abandoned this approach “The dirtiest book of all is the expurgated book,” he later said. Baudelaire would have agreed there.

One of the offending poems was called “I Sing the Body Electric,” a hymn of praise to the human body. Aside from its attention to seemingly every inch of the body inside and out, the poem presented a bold declaration for its time: that all human bodies were sacred and beautiful, no matter a person’s shape, sex, behavior, race, or social class.

Midway through the verses, he describes a slave auction—based on a brief stay in New Orleans—and highlights the dignity of the humans who were being sold there, a dignity that much of the country did not wish to see.

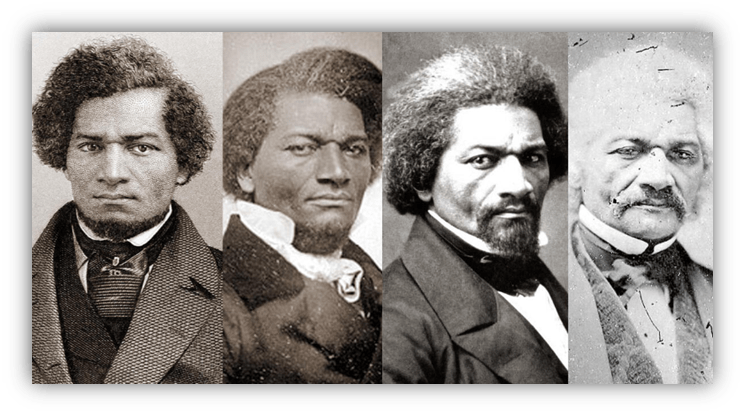

I think of Frederick Douglass, the former slave turned abolitionist, who was photographed over 160 times, more than even Abraham Lincoln.

Douglass saw in photography a true democratizing power, allowing every single person to present their dignity in pictoral form, including slaves. Whitman worked with words rather than photographs, but the detailed physicality in his poem conjures a similar sense of dignity through portraiture.

The imagery he used told a larger story about our common humanity, despite whatever social strictures may keep us apart.

Given all the pessimism that we’ve seen among the avant garde so far, should we dismiss optimistic mystics like Thoreau and Whitman as nothing but empty idealists?

As peddlers of panglossian hope-porn?

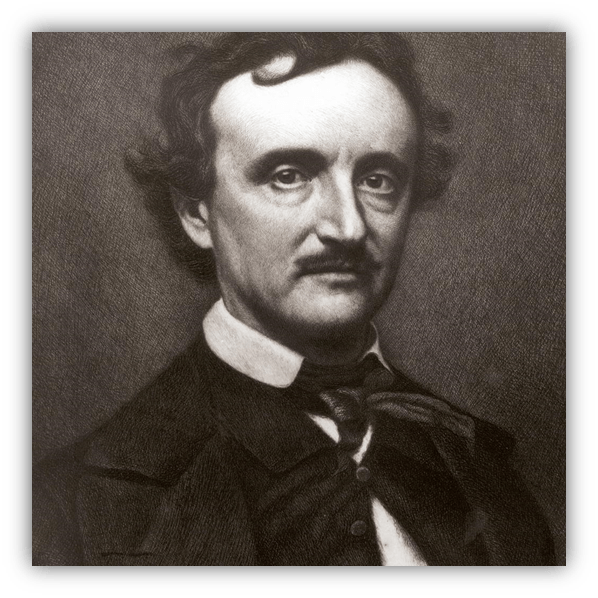

The author Edgar Allen Poe indeed dismissed the Transcendentalists on similar grounds.

Poe was more of a proper Romantic, and held a much dimmer view of human nature.

As such, the mystical revelations of Emerson was just mediocre Utopian fakery, nothing close to the truth of the world or the people in it.

While I do believe it’s important to capture the darker sides of human nature, both for documentation or real injustice and potentially for catharsis, I find that Poe’s glass-half-empty outlook doesn’t get at the full picture any more than Emerson’s does.

More importantly, the transcendentalists and their followers weren’t simply pushing feel-good optimism. They were advancing an inspiring vision of the future for citizens to work toward, and to eventually realize. They were trying to make their nation a better place to live, and sought to change hearts and minds accordingly.

Most importantly, their words were backed by their actions. While Poe was conveniently silent on the topic of slavery—the defining political issue of his day—the Transcendentalists worked for the cause of abolition, using their stature and their rhetorical gifts to rally the public against slavery.

Walt Whitman publicly advocated for the Union and against the Confederacy. He also attended to thousands of wounded soldiers during and after the Civil War.

In the early years of Reconstruction, as the public tried their best to forget the recent horrors and carry on, Whitman felt compelled to relate the realities of war in several poems.

This wasn’t blind or empty optimism. This is someone who breathed compassion and craved justice, who stayed true to himself for the good of the public.

We do need critical spirits to tell hard truths.

Cynicism is sometimes well warranted, and often understandable.

But if all we have to offer is pessimism, nothing will ever get better.

If someone can only be inspiring if they are perfect, then there’s nothing to do but hide away in dejection, and be effective nevermore.

Contributing author phylum of alexandria

These days, Whitman’s patriotism is sometimes dismissed as both mawkish and hawkish. The man certainly had his weaknesses and blind spots. He was a man, not a god. But his ability to see God in the smallest leaf, in every person he encountered, in his nation’s foundational dreams of freedom, this was real power that could be used for real good, to make the world a little better than it had been.

Even here, Walt knew what was up:

“The word “democracy” is a great word, whose history remains unwritten, because that history has yet to be enacted.”

Amen.

Speaking of unwritten histories, I look forward to writing some chapters about African American contributions to this grand cultural evolution.

In the decades following their emancipation from slavery, black communities would work to promote their own sense of autonomy and presence within the national culture and beyond.

And boy:

Did those early pioneers know how to sing the body electric.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Thanks, Phylum, for this look at some of our nation’s most essential contributors to moral and intellectual development. I’m right with you on the relative worth of cynicism. (Clever aside on “Whitman sampler,” BTW, although now I’m hankering for a little chocolate…) I look forward to your next installment.

Thanks for this Phylum, adding some much needed background for me on Emerson and Whitman. Familiar with the names they don’t get much coverage over here.

I didn’t know about I Sing The Body Electric as a poem but the title had recognition factor from the distant past. Quick search tells me that the Kids From Fame performed a song with the same title, apparently inspired by Whitman’s poem. Unlikely crossover but you never know where inspiration will take you.

I Sing the Body Electric was also used as the title of a Twilight Zone episode written by Ray Bradbury. He later turned it into a short story. One of the few instances of the TV show preceding the literary output until the practice of writing novels based on sci-fi series and movies became established.

I’m glad we have photos of these people, especially Frederick Douglas.

Thanks for this, Phylum. It’s been a while since I’ve thought about Thoreau, Emerson, etc. The last time was probably in college. I think I learned more today than I did then.

I’m currently at a conference, but thanks all!

Whitman is one of my favorite poets, and it is hard to do justice to him and his work. You pulled it off. Wonderful piece.

Hey, I learned from a very early age, Walt Whitman had to be a pretty influential dude to get one of the 3 Philly -Jersey bridges over the Delaware River named after him. 🙃

Fascinating topic of conversation Phylum, like VDog said, I learned way more from your entries than I did entire semesters in college! Very curious to see where you go next… 🙂

You gotta check out his late career sequel to “Leaves of Grass.” No one gives “Steaks of Cheese” enough love.