March 15, 1945. Paris, France:

A performance of Igor Stravinsky’s work Four Norwegian Moods is held at the Theatre de Champs Elysees, where his infamous debut of the Rite of Spring had taken place nearly 30 years earlier. The event is the third of a seven-concert series celebrating the work of this now-legendary composer.

Once again, the performance is disrupted by boos and jeers from the audience.

This time, it’s not the public reacting to his shocking new musical. It’s a protest led by young musicians who find this titan of modernism to be old and boring.

Stravinsky will get a similar reaction when he performs at the Champs Elysees in 1952.

The old guy can’t catch a break.

Yep, the times they are a-changing!

The Serial Killer

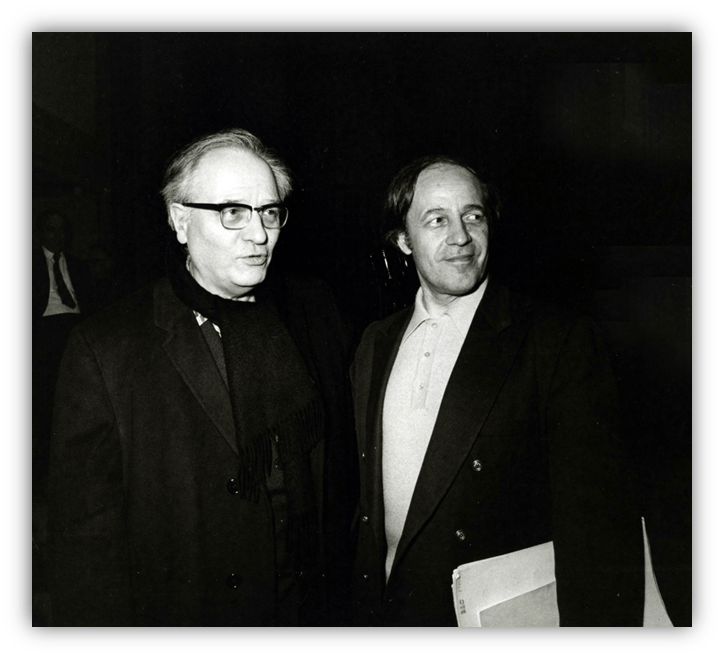

The ringleader of both protests was the French composer Pierre Boulez, the new enfant terrible of the European avant garde.

Boulez may have thought that his bratty demeanor and radical rhetoric were new and exciting, but as my last series showed, that combative style was far more predictable than any Stravinsky piece.

Still, the music that Boulez pushed did show how much the winds had changed in compositional circles, with old revolutionaries like Stravinsky struggling to keep up.

In many ways, Boulez’s music built upon innovations made by Stravinsky’s principle rival: Arnold Schoenberg from Vienna.

Schoenberg had wanted to open up traditional notions of melody and harmony in music, which traditionally greatly favored certain notes and patterns because people found them pleasant to hear.

In the first decades of the 20th century, he and his colleagues composed music that gave equal weight to all of the notes of the 12-tone “chromatic” scale.

Schoenberg further formalized the approach by creating a new rule: no repeating any note until all other notes in the scale have been included.

This was the start of 12-tone serialism.

Schoenberg’s approach yielded countless scores of melodies that most casual listeners will think of as music from someone who was rather drunk while composing.

Yet notes were only the beginning. In Olivier Messiaen’s Quartet for the End of Time – which he wrote and debuted as a prisoner of war – the tempo, duration, and dynamics of the piece were all treated as Schoenberg had treated pitch: as variables to be weighed and distributed for maximal variety of sound.

The young Boulez had studied with Messiaen, and he soon came up with his own grand unified system of “Total Serialism.” Every aspect of composition was methodically varied using the serialist method.

Sometimes the results were as violent as his overblown rhetoric, but in truth Boulez’s music more often than not sounds…random. If there was any real violence to his music, the attack was on his own sense of self in his work.

And that’s the unifying theme of this era: modern artists committing themselves to elaborate theories and laborious formal processes that served to strip their creations from that pesky mundane concern for personal expression.

In the Enlightenment era, art was made to glorify God, to celebrate the dominion of humanity over nature, or to signify the wealth and power of noble patrons.

In the late industrial and modern eras, art was often made to capture feelings and subjective emotional states. But in the middle of the 20th century, even self-expression seemed like a restriction. The new wave of innovators wanted to free their works of conscious intention, to liberate art from the shackles of the artist.

Chance of Lifetime

John Cage had studied with Schoenberg for a time, but even then he was searching for a radically different way of composing.

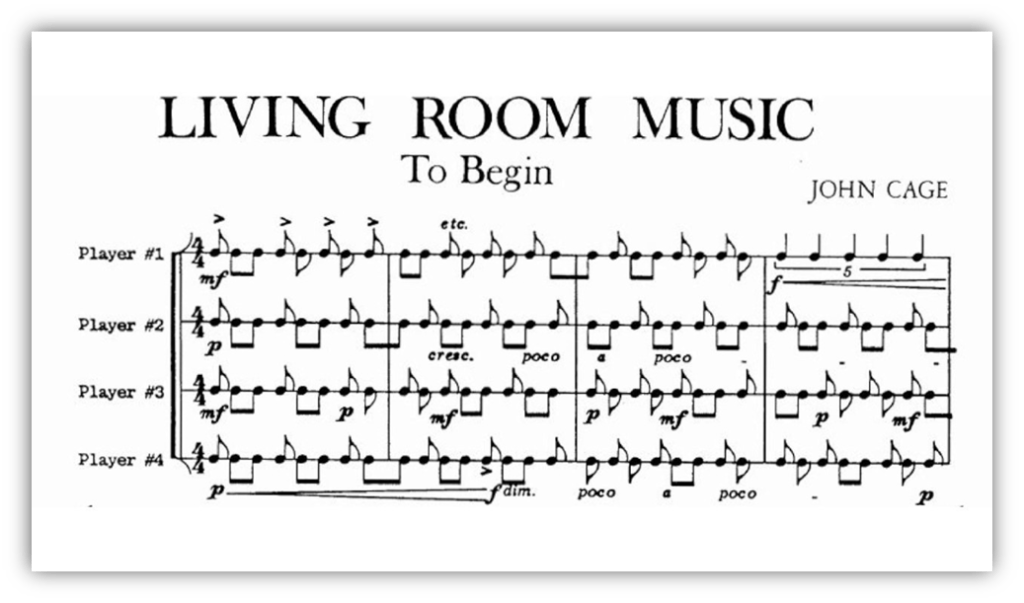

Instead of rigid rules to help him plan out a piece, John Cage wanted to leave his music up to chance. In 1951, he composed the first randomly-generated solo piano work.

Cage created a chart system that corresponded to the I Ching, the Chinese book of divination.

For every aspect of every bar, Cage rolled dice to indicate a given position of the chart that would specify the musical details to be used.

Whatever he landed upon, he would transcribe into musical notation for the score. The result was Music of Changes, a unique collection of piano sounds for which Cage was but a mere vessel. It was a pioneering effort of what he called “chance operations.”

Soon enough, Cage felt even that his use of fixed scores was a stifling habit.

He thus started to grant musicians some measure of freedom as to when and how the measures of his randomly-composed scores were played in a performance.

This new approach to chance music was named “indeterminacy.” It was music free from his personal likes and dislikes, and thus he liked it very much.

Despite their very different methods of composition, the works of Boulez and Cage can sometimes sound eerily similar.

The two had been friends once, and Boulez tried his hand at chance composition. But the volatile Boulez came to dismiss Cage as a fascist, as he did with everyone.

The Romanian composer Gyorgi Ligeti complained that both Cage and Boulez wrote works plagued by “compulsion neurosis,” which stripped them of expressive qualities. (Ligeti’s own work at this time was thoroughly modern, and yet bubbling with emotion.)

Oddly enough, it was Boulez who eventually deigned to get more expressive in his music.

For Cage, his off-kilter approach was never about throwing a tantrum; it was a Zen-inspired embrace of the world as it was. He would continue to experiment with chance composition and performance until his death in 1992.

Back to the Lab

Yes, “experiment” with composition. John Cage didn’t bother with the military term “avant garde.” Instead, he called his work “experimental music.”

His brand of bohemian radicalism had a decidedly academic flavor to it. And other modernist composers soon followed suit. Or should I say, “followed sensible suit jacket, tie optional.”

Cage put scrupulous effort into his chance compositions, yet other composers of the time outdid even him in terms of methodical rigor. They seemingly sought to bring musical creation as close as possible to the realm of scientific investigation.

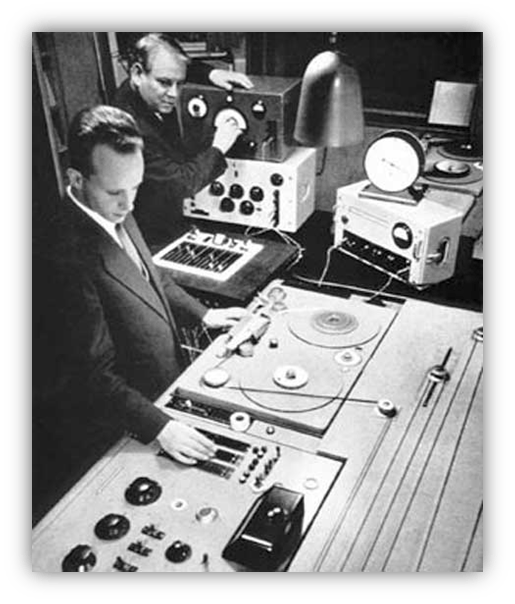

Composer Herbert Eimert collaborated with physicists Werner Meyer-Eppler and Robert Beyer to found a studio for electronic music in postwar Cologne Germany.

There they created the very first synthesized electronic music, which was composed according to scientific principles of sound and auditory perception.

Like the Dadaists of the early 20th century, “musique concrete” was a fresh and irreverent appropriation of found sounds. Unlike the Dadaists, the masters of musique concrete really put the “lab” in laborious for their intensely rigorous efforts in magnetic tape splicing and reconstruction.

Karlheinz Stockhausen took both of these approaches, as well as Boulez’s total serialism, and fashioned some of the most commanding modernist works of the era.

As such he became an icon of postwar Germany, his studious iconoclasm representing a possible path forward for the beleaguered nation.

Naturally, he perfected the image of the composer as an experimental investigator. While the famed psychologist B.F. Skinner was devising contraptions to understand animal and human behavior, Stockhausen and the rest tired away in their labs to unleash all possible musical ideas to be heard.

If you’re not inclined to think of any of these experiments as actually worth listening to, perhaps a better analogy to consider is architecture. Most people would not say that the Eiffel Tower is beautiful, or that visiting it is life-changing in any way.

Still, it’s striking. It’s unique. It’s impressive. And it’s an important slice of modern national and global culture.

So too with these major works of modernism. The experience of sitting with them is memorable, even if the tunes themselves are not.

This above analogy undoubtedly works best for Greek composer Iannis Xenakis, who actually worked as an architect and engineer as well as a musician.

In his compositions, Xenakis crafted striking blocks of sound with an overall structural design, and he often employed fancy statistical models to do so. Still not expressive per se, but thoroughly impressive.

At very least, he had listening audiences in mind, which is not always a guarantee with modernists.

Freedom or Else!

Arnold Schoenberg passed away in 1951, and afterward Stravinsky began to pay more attention to the music of his old rival.

He realized that the work of the Serialists had proven more impactful upon the contemporary music scene than his own work had.

Soon enough, he would publish his own compositions inspired by Serialist principles. Join or die, as they say. In this case, the pressure to join came from the radical individualists.

At their best, these postwar experimental works showcase a wide-eyed wonder for new and unconventional ways of hearing and appreciating sound. They also invite interpretation and discussion with respect to what they mean and what feelings they elicit.

Like the action paintings of Jackson Pollock, this was a valuable addition to the public’s engagement with art.

But at their worst, the musical modernists showed real disinterest in their audience, sometimes real contempt. Their number one concern was their own freedom to do as they wished. To hell with listeners, and even colleagues, who disagreed with them.

In fairness to Schoenberg, he criticized the more fanatical serialists he had helped to create: “I do not compose principles, but music.”

Kudos to all the modern composers who sought to open up the world of possible sounds, while still endeavoring to create something that holds power and beauty.

Something that they would deem to be music.

However those terms may be defined…

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Another notch in John Cage’s belt was his popularization of Satie’s Vexations piece after finding the score in Satie’s notes. He was the first to publish the score, and the first to arrange a public performance.

Satie’s notes say “In order to play the motif 840 times in succession, it would be advisable to prepare oneself beforehand, and in the deepest silence, by serious immobilities.” This was probably just a wry joke on Satie’s part, but Cage took the instructions seriously, and made sure it was played exactly 840 times. The performance lasted more than 18 hours, and required multiple musicians to play in shifts.

This performance here is only 12 hours long. Apologies, as you won’t be properly vexed:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U5R8xe2cCbA

I find this all very fascinating. I think you capture it all well…these experiments are valuable. Pushing the envelope to find where various boundaries are in music is a worthwhile thing to do. But while these academic endeavors are valuable, I think they rarely sound musically appealing. Weirdos.

Yeah, I’ve never had the urge to hum John Cage while in the shower. Although maybe I shouldn’t knock it before I try it?

I think some of the electronic and tape experiments sound sonically appealing, even if you don’t want to call it music. It opened the gates not just for cool production down the road, but also the ambient textures and electronic beat music that came a good deal later.

Yeah… this music all falls into the “admire (way) more than enjoy” category – fascinating stuff – thank you!

Hey, you never know. I used to hate Ligeti’s early work, but now I love it. Like, listen to it all the time love it.

Here’s a piece that you might even instantly like:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oXsRlMneOS0