The 1940s saw some classics of US cinema hit the big screen.

You had Orson Welles’ masterpiece Citizen Kane.

You had Hitchcock greats like Shadow Of a Doubt, Spellbound, and Notorious.

You had the start of film noir with titles like The Maltese Falcon and Murder My Sweet.

You also had fun horror flicks like The Wolf Man and Cat People.

But those movies are not what we’re talking about here.

Make room for the cinematic outsiders!

Our two filmmakers of focus lived very different lives. They had very different ambitions. And they had very different levels of success in achieving their dreams. But they shared some important things in common. And taken together, they can help us understand this certain moment in time for outsider films.

1. Look to the Stars

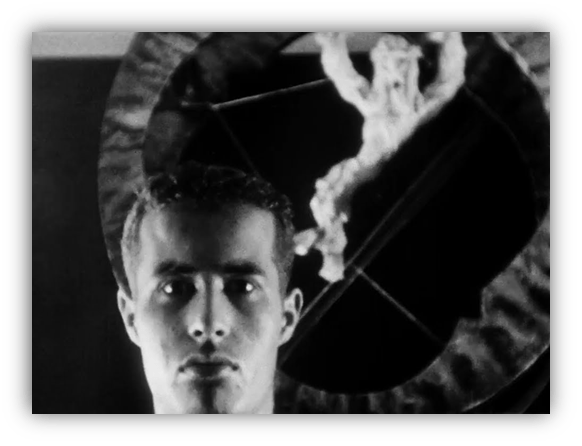

One evening in Hollywood, 1947, Dr. Alfred Kinsey stopped by the Coronet Theater to see the debut of a new independent film: “Fireworks.”

Once the screen lit up the darkened theater, a series of dreamlike images unfolded: haunting, seductive, and terrifying. The work was only 15 minutes in length, but, when caught up in the dance of its scenes, it seemed endless. Timeless. Immortal.

Kinsey was transfixed. And he was moved to purchase a print of this film for his own viewing at home.

Thus, the 20-year-old filmmaker Kenneth Anger made the first sale of his work.

He also made a new friend in Dr. Kinsey, who soon provided an opportunity to take part in some revolutionary research.

The good doctor had just recently founded the Kinsey Institute for Sex Research, where his team would run observational studies of sexual behavior.

Kenneth Anger’s participation helped to map out a pattern of variation in toe curling behavior in men during orgasm.

The 1940s were not known for their sexual liberalism, but there were exceptions. And Hollywood was a land of opportunity for such exceptions, at least discreetly.

Yet Kenneth Anger’s film was not discreet. Fireworks wasn’t pornographic by any means, but it was the most openly homoerotic film to date, by far.

Even so, its imagery went beyond simple fantasy, into dark dreams. Its scenes of violence are just as audacious as its sexual subtext.

Was it some sadomasochistic longing? Some innocent desire cut short by nightmarish fears? Or maybe something deeper?

Watching Fireworks, it’s clear that Anger was indebted to the early Surrealist films, such as Dali and Bunuel’s Un Chien Andalou.

But Fireworks in fact fused dreamlike imagery with occult symbolism, taking Anger’s work into new narrative territory. Like icon paintings in a Masonic temple, set to motion.

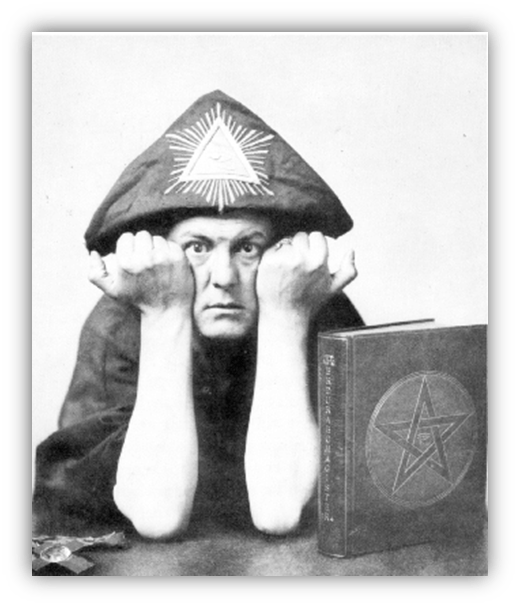

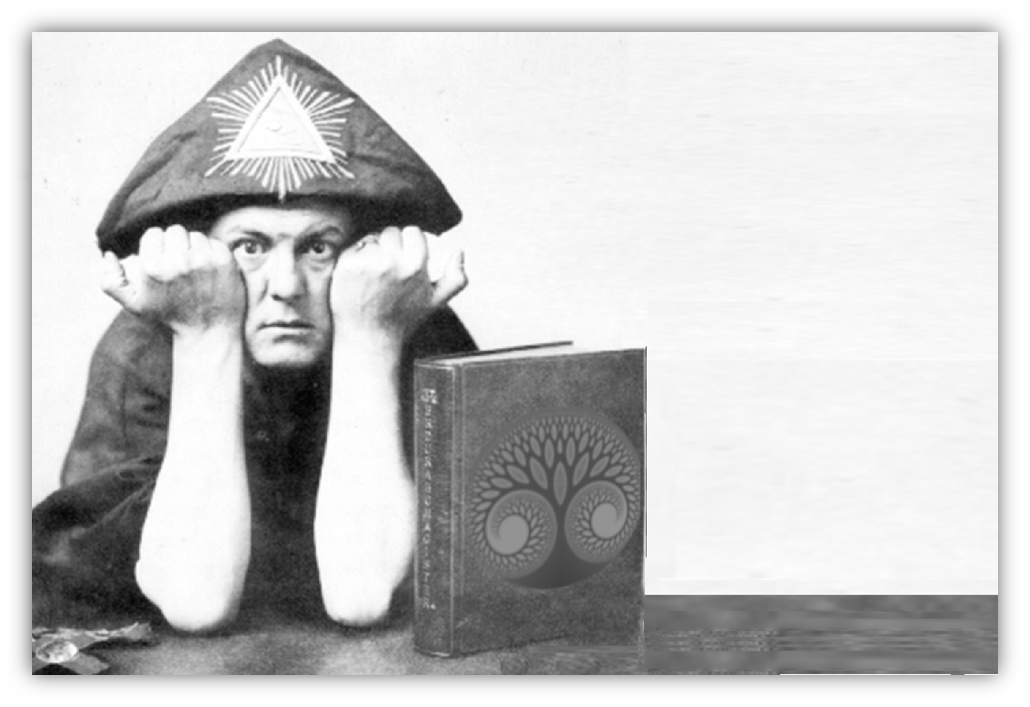

The occult magician Aleister Crowley died in the same year that Fireworks debuted. Anger was convinced this was no mere coincidence. Shortly after his family moved to Beverly Hills in 1944, the young Ken Anglemeyer was introduced to Crowley’s writings by a friend.

Fireworks and every work henceforth attempted to communicate magical ideas via his carefully considered processions of sights and sound.

Now, Crowley can be really hard to get into. Most of what he wrote was cryptic, provided as tools for guided practice and contemplation.

And he was sometimes off his gourd on drugs. While he did write some passages of simple candor, more often you have to deal with lines like “the Khabs is in the Khu, not the Khu in the Khabs!”

Thankfully, other writers have explained some of Crowley’s ideas in a way that I can understand and appreciate. The puzzling line I quoted above is actually about how every person’s soul has the light of a star within them, and as such they are the legitimate center of their own solar system. It’s an argument for the emancipation of the individual, for the exercise of free will, and for everyone to cultivate their truest selves.

Fireworks is partially based upon dreams that Anger had, but shaped into a tightly symbolic narrative of death and rebirth.

And the incandescent light of the titular fireworks represents the inmost light, to usher a new state of independence.

As painters used liquid pigments to communicate with audiences, Anger said that filmmakers conveyed their ideas with light. And light as a force for independent true will would show up in several of his subsequent works.

Most notably in his later film Lucifer Rising. Don’t forget: the name Lucifer translates to “bringer of light.”

In many ways, Anger was voicing the same aspiration as the Beats from around the same time, albeit coming at it from a different medium and narrative approach. A marginalized eccentric was demanding the right to be who they wanted to be, to live their life openly and without shame.

2. The Angora Within

In 1947, the same year that Kenneth Anger released Fireworks, Edward D. Wood Jr moved to Hollywood, CA.

Wood was originally from Poughkeepsie, NY, where he spent his early life before serving in the Marine Corps following Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor.

Shortly after his honorable discharge, Wood packed up and moved across the country to Tinseltown, where he hoped to find success as a screenwriter or director.

Alas, he did not find the success he was seeking. He never did. But Wood did find some minor jobs in writing and directing commercials. And on his own time, he wrote and directed some plays for theater.

For some writing projects, he would use pen names, one of them being female: “Ann Gora.” Why? The answer would only become apparent later.

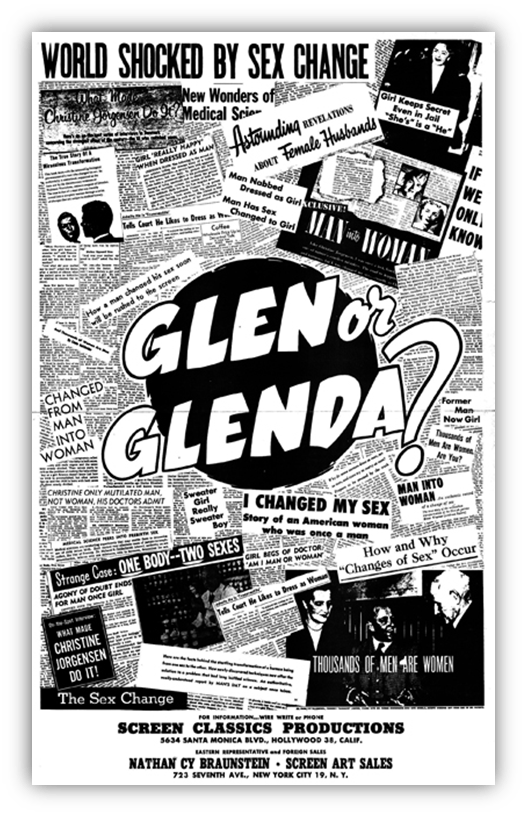

In 1953, an opportunity presented itself in the newspaper’s classified section. Wood saw an ad for a new film to be made based on Christine Jorgensen, an Army veteran who was all over the tabloids as the first person to get a sex reassignment surgery.

Wood met with producer George Weiss, who wanted a cheap trash flick to cash in on the press surrounding Jorgensen.

Weiss had tried to get Jorgensen herself to star in the film, but his offers were turned down. After all, the story of Jorgensen transition became public against her will, due to a leak to the press.

Weiss was determined to make the film no matter what; he would simply make it a knock-off story that was close enough to capitalize on the moment. He planned to call it: I Changed My Sex.

Wood insisted to Weiss that he would be particularly well suited to write and direct the film. Not because he had changed his sex. But because he too lived with a secret. He often dressed like a woman in the privacy of his own home, particularly favoring luxuriously soft angora sweaters. He would often wear bras and panties underneath the suits he wore. And in fact had worn them under his military uniform while fighting in Japan. This otherwise normal man was engaging in transvestism.

Weiss had major doubts about the prospect, but what the heck? He gave Wood four days to shoot a film that he could distribute to make a profit.

Unfortunately for Weiss, the film that was given to him was nothing close to what he had wanted. It wasn’t even called I Changed My Sex.

It was now Glen or Glenda.

And most of the film centered on the titular duality of Glen/Glenda, and focused on transvestism. There was a side story about the sex reassignment of Alan/Ann, but it constituted less than a third of the film.

Even worse, the movie made no sense at all. It framed itself as a docudrama, but veered into strange and incoherent directions. Random stock images appeared out of nowhere. Outlandish dream sequences pushed the story into gaudy surrealism.

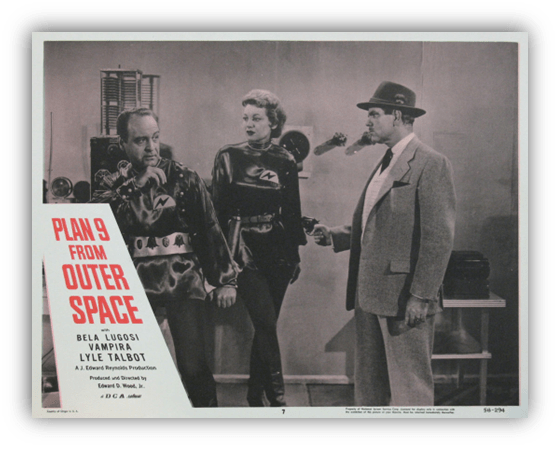

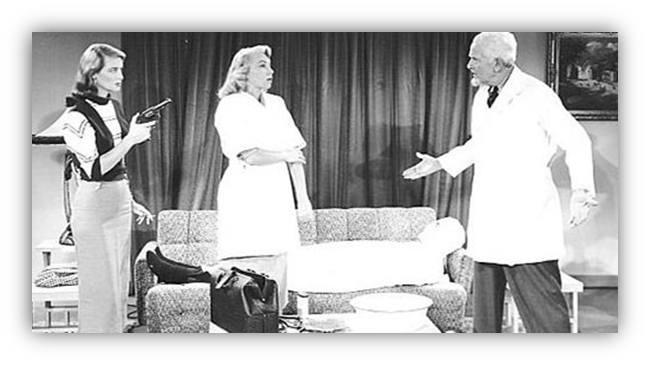

Glen or Glenda notably featured the once-legendary horror film actor Bela Lugosi, who Wood had recently befriended.

Yet Lugosi’s presence was most enigmatic of all: he sat in a mad scientist’s laboratory next to a human skeleton, and he rambled incoherently about big green dragons and puppy dog tails. Audiences would be too confused to understand anything about the film, let alone be titillated by it.

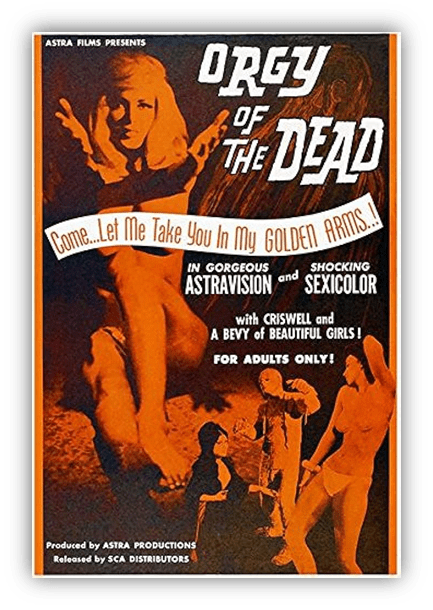

Wood went on to make more films that are now considered to be cult favorites for their astonishingly impressive terribleness:

Bride of the Monster,

Plan 9 From Outer Space,

and Orgy of the Dead.

Most of them were in the sci and horror vein, where the use of Lugosi made a lot more sense. The scripts made maybe a little more sense than Glen or Glenda, but incoherent editing, wooden acting, and laughably bad special effects ensured that any popularity Wood got would be due to infamy rather than fame.

But make no mistake: Glen or Glenda is a radically inventive film. Wood was apparently trying to emulate Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane with his use of stock footage, and he ended up channeling the spirit of the experimental Soviet filmmaker Dziga Vertov.

His madcap dream sequences felt straight out of the Swedish docudrama Haxan. Maybe he failed to make the movie that was in his head, but this was accidental avant garde!

It was also a great example of camp in film.

“Camp” as a concept goes way back, at least to the early 19th century. Its earliest connotations had to do with ostentatious display, exaggeration, theatricality, and homosexuality. Yet Susan Sontag later expounded on the style in a way that sets it a bit apart from the earlier understanding. For instance: “The ultimate camp statement: it’s good because it’s awful.” Welcome to the postmodern era.

Kenneth Anger and Ed Wood both presented films that engaged with this new postmodern variation on camp in film. With Anger, it was more accentuated in his films that followed Fireworks.

For instance, Puce Moment, The Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, and especially his pop art masterpiece Scorpio Rising.

With Ed Wood, pretty much everything he made had camp value, though it wasn’t intentional like it was with Anger. But both of them made works that seem campier in this new sense than, say, the ornate excesses of Jean Cocteau.

In this new world, bad taste was a thing of beauty. Culture was a set of symbols to be challenged, redefined, and transformed.

I don’t think that Wood and Anger ever met, although they were active in Hollywood around the same time.

Perhaps they crossed paths without realizing it. In any event, I feel like their early films crossed paths in aesthetic space, in the Promethean incandescence of the small theater screens, and the minds they fertilized. I for one can’t imagine the films of David Lynch without either of them.

I think it’s fitting and somewhat poetic that Wood, who mostly kept his transvestism secret, would have his art redeemed over time via an aesthetic lens that had mostly developed within queer artistic communities: the somewhat cynical, always playful aesthetic lens of camp.

Now he’s part of the broader family, at least queer-adjacent. And now nerds like me can wax ecstatic about the brilliance of his failed documentary. And revel in his dogged commitment to his outsider vision, to hell with what everyone else was thinking.

I might even go so far as to say that it’s a little bit of magic at work.

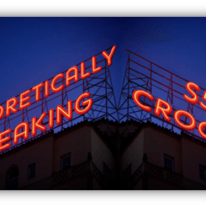

The subversive glamor of underground cinema. Abracadabra!

I guess Ken knew what he was doing.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

I’m afraid I’ve never heard of Fireworks and I’ve only seen pieces of Glen Or Glenda, and I think they were part of Mystery Science Theater 3000’s riff on it. I do like a bit of camp though, so I’ll have to seek them out. I don’t always buy the so-bad-it’s-good concept (though I’ll make an exception for Zardoz) but I’m willing to give it a try. Thanks, Phylum!

Love MST3K. We introduced our son-in-law to it a several years ago, and I don’t know if I’ve laughed as hard since. His utter bewilderment was wonderful.

My favorite installment remains Manos the Hands of Fate. I tried to watch the film without their banter, and simply could not endure.

“Manos: The Hands of Fate” is just so, so awful that I feel even the MST3K folks could not lift it up. That said, my favorite MST3K movie is “Mitchell”, so what do I know?

I mean, my idea of a good time is a “Food Fight” / “God’s Not Dead” double feature, so maybe I’m just a glutton for punishment!

For a start, you might want to try Plan 9 or Bride of the Monster. They’re perfect MST3K material.

After watching David Lynch’s Eraserhead a few times, I became convinced that he was a big Glen or Glenda fan…and it turns out that it was indeed a huge influence on him. All of that is to say, if you like Eraserhead, you might like Glen or Glenda quite a bit. But if you want more of a breezily bad movie experience, those other films fit the bill.

Now, Kenneth Anger is another breed entirely. Lynch takes from him as well, but some other points of reference are Andy Warhol/Paul Morrissey, and John Waters. If you like Trash, or Flesh, or Pink Flamingoes, you could probably get into Kenneth Anger. And definitely so if you like Matthew Barney’s Cremaster movies. Huge influence.

Pink Flamingos was showing somewhere near or on campus when I was in college, and a bunch of guys on my dorm floor went to see it.

Mileage varied.

“Mileage varied.”

That’s probably quite the understatement.

I was gonna say, if you’re going to talk about camp and trash, you have to lead to John Waters, the reigning demigod of all things trash cinema.

Filth are my politics. Filth is my life!

Mr. B Natural is my favorite. The MST guys expertly brought the subtext to the surface. Did the filmmakers know what they were invoking? Maybe. I watched one of Time/Warner’s random free movies a few weeks ago. The inspiration behind Mr. B Natural might’ve been Billy Wilder’s The Major and the Minor. The B stands for Billy.

Mr. B Natural is a winner.

What did you think of the movie, “Ed Wood”? I didn’t really know enough about the source material at the time to judge whether it was an accurate portrayal, or if it was closer to Ed’s interpretation of Christine Jorgensen’s story. As in, unrecognizable.

I love Ed Wood. It was what turned me onto his films in the first place, and to the whole notion of trash cinema.

It’s pretty faithful to the broad beats of his life, at least up to the debut of Plan 9. Notably, the follow-up text at the movie’s end mentions in passing that Ed Wood’s career never took off, he got divorced, and fell deep into alcoholism.

At least they were honest about that, but it’s also a testament to how much they shoehorned his life story into an inspiring “underdog hero” narrative. To say nothing of its clear stylistic debt to Orson Welles’ films. Also, judging from his appearances in his own films, Wood was much more of a wallflower than Depp portrayed him to be.

All of these changes add to its appeal as a film, but less so its value as biography.

I’m more familiar with Ed Wood thanks to the Tim Burton movie and seeing clips of his movies. Which tended to be delivered out of context for maximum effect in proving his ineptness. It’s been a long time since I saw Ed Wood the film, my memory is that it was a more sympathetic portrayal than his general reputation but like Rollerboogie I’d be interested to know your thoughts given your closer to the material.

I think you’re referring to lovethisconcept. I actually hadn’t weighed in on this yet, JJ, but I was going to, so maybe you read my mind? Yes, I would be interested to know Phylum’s thoughts on the movie Ed Wood as well. As for me, I absolutely loved it. I don’t know how accurate of a portrayal it was, but I want to say it was likely pretty darn close.

You’re quite right, my mistake. Too late to use the edit button and cover my tracks. Best cross off attention to detail off my CV.

His ineptness was perfectly portrayed. What’s exaggerated is the theatrical quirkiness of all of the characters outside of the films. And, even the “bad” over-acting they do in Ed Wood is far more engaging than the wooden delivery in the real films!

But as I said, Glen or Glenda is an accidental masterpiece of avant garde. For all its flaws and failures, it really is brilliant.

As my screen name would indicate, I am a fan of accidental camp. Intentional camp, not as much so, though I’m always game. Not too into experimental films, though I am aware of Kenneth Anger and Hollywood Babylon.

Was not expecting the name Aleister Crowley to come up. He was mentioned a lot in the born-again/evangelical circles I frequented, as those were the days of Satanic Panic. His name came up prominently in Bob Larson’s book warning Christian teens against the evils of rock and roll, being that a number of British hard rockers were into him particularly in the late 60s to the 70s. I recall that Jimmy Page bought his house, and Ozzy had a song about him off of Blizzard of Oz. This is straying far from point, but a few years ago, we were at a 4th of July Parade and as a float went by, featuring musicians from a church playing a praise song, some guy behind me yelled out at them, “Play Mr Crowley!” I laughed out loud.

I wanted to mention Hollywood Babylon, but I decided to keep the piece short and tight. There’s something about Anger’s “creative” takes on celebrity history that dovetails rather well with his take on cinema as magic and cultural symbology. Not to mention, it’s another type of fixation on the stars.

But really, I’ll be honest, the main reason I wanted to mention it is because it’s the name of a Misfits song. And then I’d have a twofer in Misfits references, along with Plan 9 (their old label). Alas…

Ah, Satanic Panic! Dated a BAC back in the (long past) day with whom I attended church as part of a ‘you support me, I support you’ understanding (she came to all my softball games). One of the services was part of the ‘SP’ groundswell aimed at the evils of rock and roll. I remember AC/DC and KISS being a large part of the proceedings. Funny that those bands are almost considered quaint today.

I love this post.

When I was in my church youth group, our youth pastor played a video about Satanic influence on heavy metal. Me and most of my friends attending that youth group were big fans of the bands, so we were rocking out to the cautionary video. Future installments of the heavy metal Satanic panic video series were NOT shown.

That’s fantastic. That’s the kind of propaganda we were exposed to as well. Even as a 12 year old I knew something was off. I was like “if all rock and roll is evil, how do you explain “Jesus Is Just Alright With Me”?

Or “Spirit in the Sky”…

Or would that be too folky to qualify as rock?

I was so sure Def Leppard was saying, “Jesus of Nazareth, go to hell” at the end of “Love Bites.” And I loved the song in spite of that. Small town Christian America has an indelible effect on your psyche. Don’t get me started how much I was fucked up in the name of the Lord… *smh*

I was not from a small town, but I know of what you speak. On a bulletin board at my high school, I anonymously posted an article that claimed Led Zeppelin had recorded the spoken words “Here’s to my sweet Satan” backwards on the song “Stairway to Heaven”. Every time it was torn down or defaced, I would post another copy, for several months. And this was long before I cut myself off from nearly all “secular” music for a time in college and post-college.

Spirit in the Sky was deemed dubious by the anti-rock folks as I recall because it combined references to Jesus with so-called Native American spirituality. I did know a guitar group at church years later that wanted to play it, but not sure if they got the chance to do it before the traditionally-minded pastor showed them the door for playing “Let it Be” at Confirmation in front of the bishop.

I had played “Let it Be” in church too prior to that, but I never got in trouble for it. I guess you had to kind of pick your spots.

My parents didn’t seem obsessed with Satanism in music, though I did learn a healthy fear of Dungeons and Dragons. Such a surprise when I attended a Strategy and Tactics meetup in high school. And a let down!

My mom kind of was, but most of the messaging I was getting was from my prayer group leaders and books they would recommend.

The D and D panic in the evangelical community was a very real thing.

I want to keep things upbeat. I’ll be subtle.

John Darnielle’s last novel, Devil House, indirectly references an episode of Satanic Panic. Darnielle is from the same state as the episode.

Okay. Lighter fare.

Do you remember a low-budget horror film called The Gate? It’s the only film I can think of that addresses the urban myth of secret messages in heavy metal records when played backwards.

I grew up a heathen. But the cover art for those early Ozzy Osbourne albums had a visceral effect on me. I couldn’t separate the person from the persona as depicted. I really thought that was how Ozzy Osbourne spent his days and nights.

I was in both fear and awe of rock stars like Ozzy for much of the same reason. It really was the album covers that set it off.

I’ve come to think of Aleister Crowley as the Ozzy Osbourne of the early 20th century. Terrifying to some, campy to others, thoroughly decadent to all.