I teach Senior Seminar, a class designed to assist students preparing for college. Since the application process happens early in the year, in our first week, we dived into writing essays to meet the prompt requirements.

As a class, we chose prompt #5 – a chance to discuss an event in their lives which shaped them, and how.

Most of my students chose an event in their life which was traumatic: the loss of a loved one, a catastrophic injury, or a friend taking a wayward path in life. Others used the birth of a younger sibling, a monumental event in its own right. I tried, unsuccessfully, to suggest admissions offices would look more favorably on the essays that were able to take a minor event in one’s life, and create a story from it.

Students didn’t think it could be done in under 650 words, so I thought I’d give it a shot to prove them wrong.

I have memories of conversations I had with my parents as a small child, snippets of which they have no recollection, yet stand out, while the more important things like cleaning my ears slipped by the wayside.

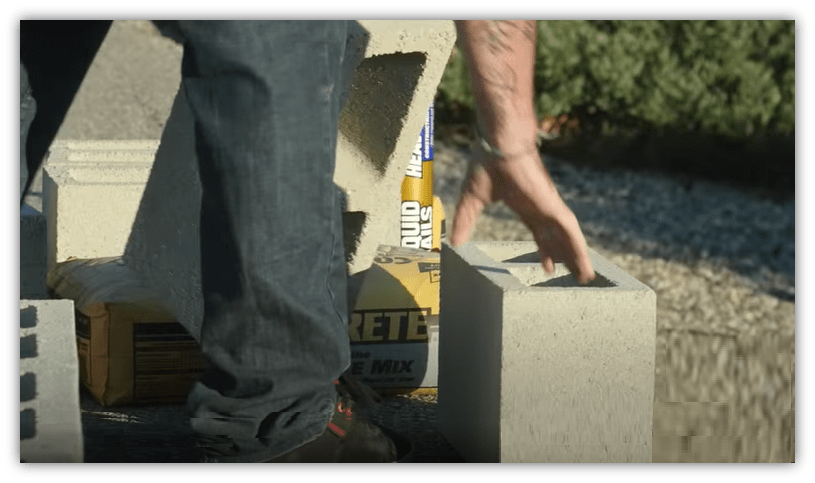

In particular, I remember a time my father and I were working in our backyard, digging up cinder blocks that lined our driveway and replacing it with tar-covered wood beams. My dad wore a wife-beater, showing off his sweaty biceps. He had a tattoo on his arm, and I asked him about it.

My father stuck his shovel into the ground, leaned on it and looked at me.

“Son”¸ he began, “I got this the summer I spent at the shore. I thought it was cool for about two days, tattooing my nickname on my arm. I’ve regretted it ever since. Look at it today: the color’s bled, my muscles sag, and I’m stuck with it for the rest of my life.”

Today, tattoos are extremely popular, but because of that insignificant conversation my father and I had when I was eight, I’ve never wanted one. My brother has at least ten; my wife wanted to get one when we married. I protested, suggesting (jokingly) that a pre-nuptial agreement might be in order.

She never had it done.

Years later after my father passed, I talked to my favorite aunt about my father’s life growing up. My father never spoke about his teenage years – I knew he had a history to hide, but I didn’t know what. The stories he did share came from his youth.

For instance, my grandmother was a harsh racist; and my father told a story about bringing a black friend home from school one day. When she saw an African-American in her house, she grabbed an extension cord and ran after him screaming the N-word, and threatened to whip him. The boy fled, embarrassed but unharmed. Instead, my father received the angry end of a racist rant, both physically and verbally.

My aunt suggested that my father hadn’t maintained such an innocent position either. She told of times my father engaged in his own racist actions as a young man. It turned out that he had regularly gotten into racial fights, and more than once found himself in jail due to his actions, the most serious of which took him before a judge… stories I never heard from his mouth.

My father passed away twenty years ago, but this novel view of him gave me an epiphany, as I saw the conversation we had in a new light. My father got his tattoo in the summer of ’66, well after his issues with race and the police. He married less than two years later; I followed shortly after. By the time we had that conversation, my father’s past was long gone.

My father coached our Little League team, assisted by the African-American father of my best friend. We attended our African-American neighbor’s son’s wedding.

There was never any hint of a previous life, one tainted with discrimination and anger.

My father vacationed at the Jersey shore that year he got his tattoo, spending his days in the sun. He was blond-haired and blue-eyed, a true Aryan, if one ever existed. The more time he spent in the sun, the lighter his hair got, and at some point during that summer, my father tattooed his nickname on his arm.

Maybe he was drunk. Maybe he didn’t realize the alternate meaning initially.

But under that hot sun, quizzed by an eight-year old, I’m sure he understood my sudden interest in his arm, and the importance of being a parent. In that moment, he changed my life, for reasons I didn’t understand until recently.

His nickname?

Whitey.

624 words. Best I could do.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “heart” upvote!

Deftly done, sir! Concise storytelling is a great skill to have. Hopefully your students were inspired to shoot for that goal.

Your great-grandmother sounds a bit like my grandmother on my mother’s side. A woman who turned away her own daughter and her family when they traveled several states to visit her, because we had a black infant foster child in tow. There are varying degrees of racism, and she was a deeply entrenched ideological racist, one who bragged that she had the same birthday as Adolf Hitler. Thankfully, I only saw her once in my life.

It sounds like your dad’s racial hangups were not as deeply entrenched as his, or my, grandmother. I don’t know where you come from, but even when I was a kid, many of Philadelphia’s neighborhoods were de facto racially segregated, so walking into some of the rougher areas was doubly unwise if you looked different from the other people in the neighborhood. Not to say that neighborhood turf wars can’t be rooted in historical racism, or that real damage can’t be done by young kids just trying to be tough, but at the very least it seems like his hangups could be overcome over time, given the right incentives. Being one of those major incentives, perhaps we should thank you as well. 🙂

I’m from outside Philly, and lived there for a while.

One of my favorite bars was Krupa’s, at 27th and Brown. It is a “neighborhood” bar (don’t say “dive bar” to the owner), and one night the bartender, a Fairmount lifer was tending when a black man walked in.

Whenever anyone new entered the bar, they received the Krupa Stare.

Joe asked him what he wanted, then served him, then they struck up a conversation. Turned out the man was from north of Gerard, just three blocks away, yet he had never set foot in Krupa’s.

The two men reminisced while I listened. The black man told Joe he wouldn’t been allowed in Krupa’s years earlier, or in this neighborhood: he would’ve had the crap kicked out of him walking south of Gerard.

Joe laughed. Ya know what? I would’ve had my ass kicked if I walked NORTH of Gerard!

The two of them laughed, and continued talking about the Good Ole Days, while I remained a fly on the wall.

Great memory.

I’m from Northeast Philly, so one of my favorite haunts was the Gray Lodge…which I just learned has since closed. 🙁

Beautiful story thegue.

Great stuff, thegue.

I’d say this was a success. You used the economy of this form to include so much: race; history; nostalgia, culture. Well done!

I can definitely say that this will stick with me–and prompt me to think about similar experiences in my family.

Best you could do? The best you can is good enough, more than good enough. Finely crafted, not a word wasted and did exactly what you set out to do. Takes a minor event and weaves in family history, drama and social commentary. Great example of less is more.

Your father was a good guy. He changed as the social mores of the time changed. Where I live, there was a hierarchy back, back, back in the day among Asians. My grandmother was disowned by her family when she married outside her race. Likewise, she wasn’t accepted by my grandfather’s family. There’s a whole bunch of relatives I never met as a result.

I remember standing in front of the picture window at their home, watching them putter around the yard, thinking: Wow. I’m looking at “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner”(in real time, I thought “rebels”) working the bougainvillea.

The only Whitey I know is the pitcher Whitey Ford. When Ford passed away, I came away with a good feeling about him after reading his obituary. I double-checked as to why that was. Elston Howard was the first black player to suit up for the Yankees. Whitey must have made Howard feel welcome. He gave Ford the nickname “The Chairman of the Board”.

Great story.

It’s a universal one.

Excellent example to follow, thegue, both with your writing and with your dad.

Setup, backstory, payoff, a modern day Aesop Fable of 650 words or less. Terrific writing.

And your dad certainly sounds as though he became an extremely wise man as he grew older – he recognized his actions as a youngster were not proper/legal/ethical etc., and actually chose to grow as a person by learning from his mistakes. Those are good people, and the world does not have enough of these wise folks unfortunately.

Excellent job, thegue. It’s really difficult to work with high school seniors, because they either want to go way big and exaggerate or way generic and kitchen-sink. Your writing is both intimate and specific, and that’s exactly what these students needed to see (and learn). Thanks for sharing it with us, too.

Nice one thegue!

I used to write short stories and poems fairly regularly. Writing for this website has brought back my itch for writing again after nearly a couple of decades off.

Thanks for the inspiration!

And thanks to mt for creating this awesome venue. I’ll get another piece ready soon brother, if you have room for it.

Always a place for you here, Pauly. We look forward to it.

Thanks to you and everyone for your incredible support and kindness.

Excellent job Marc. Your Dad was awesome. He steered me away from some sticky situations. It was his conversations that led me to make some major life changes. He’d be so proud of you.

Hello, Jules,

Welcome to tnocs.com!