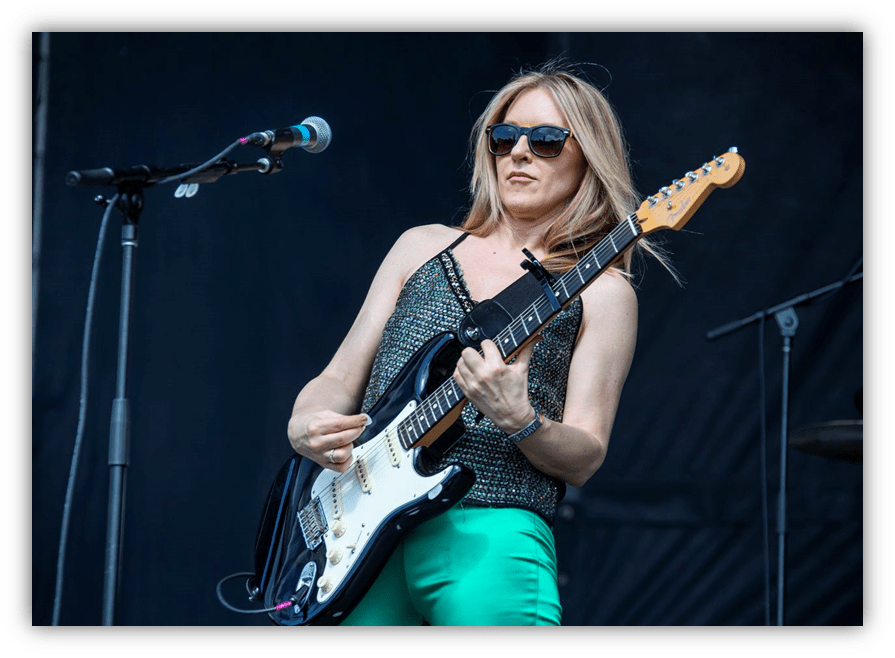

Liz Phair looked like the girl next door, the kind of gal who wanted “letters and sodas.” Your kid sister who aced her SATs and got into Barnard. Or perhaps the fifth Go-Go. But when she opened her mouth, the Chicago native sang about sex with a clinical specificity that rivaled The Purple One.

More Prince-ess than Belinda Carlisle.

Phair is not how you pictured Nikki, of Darling Nikki notoriety, a “sex fiend”, because she looked so normal, more flesh than fantasy: A Living Human Girl. In 1993, it was revolutionary. Liz Phair didn’t look like a rock star. But she was, and depending on the company you kept; she was “indie-famous” before the term was coined.

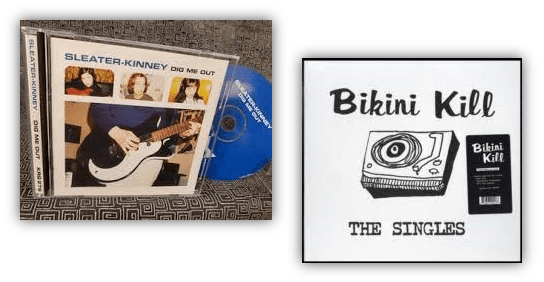

And then, there was Olympia, Washington. You may have read about a label called Kill Rock Stars, the official headquarters of “riot grrl”, where all the punk rockers were women. It’s not hard to imagine the self-stylized “b*****queen” being in the know about an early version of Rebel Girl, and then buying the Bikini Kill 7-inch single, New Radio/Rebel Girl, in which frontwoman Kathleen Hanna caterwauls like a banshee.

Phair and Hanna were kindred spirits. They were both singer-songwriters who inspired a lot of women, and you can count Greta Gerwig as one of them, during her formative years in Joan Didion country.

You can tell. As recounted ad infinitum whenever Phair’s classic debut album gets written up, the legend goes that it was a response to Exile On Main Street. In similar fashion, Ladybird has something to say about Pretty In Pink, Gerwig’s unofficial remake of the 1986 John Hughes-produced film, directed by Howard Deutch.

Gerwig feminizes the patriarchal text, a reimagining that, for some Gen X’ers, may muddle their uncomplicated nostalgia. The song is her method; an entry point to a reconstruction disseminated through the juxtaposition of Alanis Morrissette and The Psychedelic Furs, in which Hand in My Pocket and Pretty in Pink define Christine McPherson (Saoirse Ronan) and Andie Walsh (Molly Ringwald), respectively, as an insight to how the filmmaker really feels about his/her protagonist.

Some motion pictures escape from their time capsule and transcend from the decade in which they were made. A film out of time, while other movies remain stuck in an echo chamber of dated social norms: no better, no worse ilk. John Hughes’ oeuvre, his auteur years (1984-1987), albeit entertaining, has not aged particularly well. Rather than write an op-ed in the style of film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum, who fed Ingmar Bergman films into a wood chipper, Gerwig put on her hard hat and renovated Pretty in Pink, going so far as adding a new room of her own design. The hammer and nails that the late John Hughes used in building a filmic edifice for adolescent girls to live vicariously in, Gerwig razes to the ground.

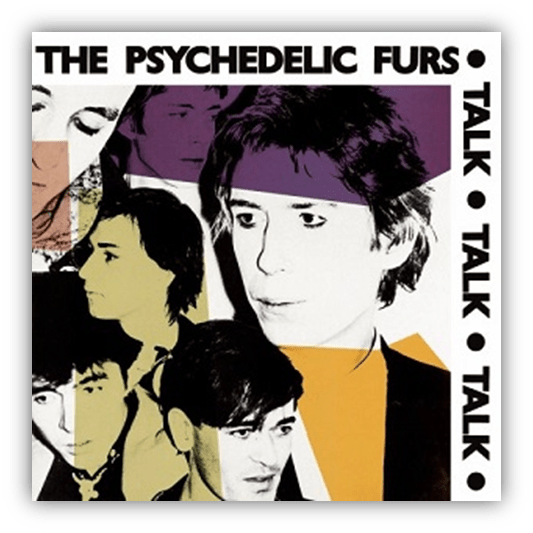

With Ladybird, the millennial filmmaker lays out a blueprint that solves a long-standing conundrum: “Why do the lyrics describe an Andie that is unrecognizable to the girl we on the screen?” The Psychedelic Furs title song, a near-hit for the scruffy London new wavers from their third album Talk Talk Talk, references a girl from an altogether different filmic world. The chorus in isolation, dislocated from the song as a whole, jibes: “Isn’t she pretty in pink?” A rhetorical question we associate with her prom dress, we’re offered a brief reprieve from the dissonance of verses like this:

All of her lovers all talk of her notes

And the flowers that they never sent

And wasn’t she easy?

Isn’t she pretty in pink?

Pretty In Pink creates a good girl/bad girl binary, in which no binary should exist. Richard Butler sounds like he’s referring to Aileen Wuornos as a teen. Hughes ascribes the titular song to reflect the POV, seemingly, of the antagonist, Steff (James Spader), a trust fund baby whose propositioning of Andie in the school parking lot, functions as endorsed slander in 4/4 time.

This incongruity between song and subject conveys an undercurrent of misogyny and class consciousness, as if the film is harboring a secret, something you can’t quite put a finger on. The “auteur of adolescent angst”, a music aficionado, buries his connotative intentions clandestinely, written in invisible ink through the medium of vinyl imports, unbeknownst to the hoi polloi. It takes “black light”, emitting from a latent totem, a customized Wood’s lamp, a tool of the music obsessive whose shining unearths the discographic obscurantism that breaches the mis-en-scene without detection, minutiae known only to subculturalists familiar with the fringes of popular art.

Pretty in Pink opens side one of Talk Talk Talk, but it’s UK counterpart drops the track down a notch, sandwiched between Dumb Waiters and I Wanna Sleep with You. The latter song’s immediate proximity to Pretty in Pink, the audio embodiment of Andie Walsh, leaves behind the fingerprints of a filmmaker made visible by ultraviolet fluorescents, revealing to the audiophilic detective confirmation of an intended autosuggestion playing synchronously below the filmic surface. I Wanna Sleep with You segues into Pretty in Pink, an affirmation of the conspiratorial pact between screenwriter and antagonist.

It takes a woman’s touch. Gerwig undoes the performative murder Hughes commits on his female characters, an emotional violence that snuffs out what made the girl uniquely her. For example, in The Breakfast Club, the lipstick tube functions as a knife, when Claire (Molly Ringwald) acts as a proxy for the filmmaker’s underlying slasher sensibilities. Allison (Ally Sheedy) undergoes a gratuitous makeover, in which Claire assails the goth with Revlon, leaving behind lips red like blood. She needed to Reject All-American. But Kathleen Hanna had to happen; her imminent happening informs Ladybird, an update of the twentieth century teen movie for Generation Z.

Whereas Hughes made good use of British music royalty to make Andie Walsh seem cool, Gerwig hightails it the opposite way, making judicious use of popular music without resorting to mixtape pyrotechnics as a shortcut to shoring up Christine’s persona. As a corrective measure for John Hughes’ misinterpretation of Pretty in Pink, Alanis Morrissette’s Hand in My Pocket, the second single from her album Jagged Little Pill plays over the radio as Larry McPherson (Tracy Letts), Christine’s father, drives his daughter to her fancy private school.

Finally, at long last, filmmaker and subject are in simpatico, linked together by music apropos of what the audience sees, in frame, and hears, in abstract. Morrissette sings: “I’m broke but I’m happy/I’m poor but I’m kind/I’m short but I’m healthy, yeah.” Hand in My Pocket, a feminist-lite Statement of Vindication, doubles as a thematic bridge to the high school musical audition scene, in which Christine tells Father Leviatch (Stephen McKinley), the director (read: John Hughes): “It is given to me by me. I gave it to myself,” when asked about her anthropomorphic nickname.

On a performative level, Gerwig gives us the illusion that Christine chooses her own theme song, suggestive of Andie Walsh, if granted the same “there is no author” simulacrum of autonomy, may have picked Suzanne Vega’s Left of Center, the only solo female artist on the Pretty In Pink soundtrack.

“Left of center” characterizes Greta Gerwig’s matriculating years, receiving her BA from Barnard, majoring in English, and raised as a Unitarian Universalist.

But Gerwig doesn’t telegraph her feminist credentials by overwhelming Ladybird with Bratmobile and Huggy Bear bangers. The heady filmmaker instead sublimates her ideology throughout the narrative with misdirecting music cues, going so far as utilizing The Dave Matthews Band’s Crash into Me as a tool of benevolent fascism to obfuscate the rebel girl’s yell. She’s a smuggler, as Martin Scorsese would put it. Smuggling was how a director working under the Hays Code avoided his film from being bowdlerized by Hollywood-sanctioned philistines.

Gerwig’s snuggling is less of a censorship issue than Easter egg hunt. The eggs are coded, and in order to be a code breaker, you need to know your indie rock; you need an arch-hipster’s cognizance to peek beneath the floorboards and see “the water flowing underground” whereas the riffraff see just plain ol’ dirt.

“Hey, I’m like Keith Richards. I’m just happy to be anywhere,” Larry, a clinically-depressed computer programmer, says, staring down unemployment due to his outdated skill-set and advanced age. For a moment, the audience glimpses his former self; the halcyon years when he and Marion (Laurie Metcalf), his wife, thought their current residence was a starter house.

For the deft Anglophile, “happy” is more than a state of mind, a throwaway adjective, a purported emotion brimming with irony. Happy, a minor hit (#22) for The Rolling Stones opens side three of Exile On Main Street, featuring Richards on lead vocal. Main Street could also be the road that the workforce exile drives his daughter on. With the advent of Ladybird, the audience can see from the other side of the prism how Pretty in Pink vilifies Andie’s mom for leaving her husband and daughter. Ms. Walsh is alluded to on Christine’s pink cast that protects her arm. “FU MOM” vociferates a festering anger that spans across generations, measured in mimetic time.

The shrieking Christine, whose mother wants her to attend college in-state and the pining Andie Walsh, who depends on Iona (Annie Potts), her boss at the record store, for pocket money and maternal love, have in common, perfect pitch for cacophony. Whereas Ms. Walsh was staring down a lifetime of getting by and split, Marion stuck it out, pulling down double shifts as an obstetrician nurse. Her industry pays the bills.

Ladybird is the portrait of a young antihero.

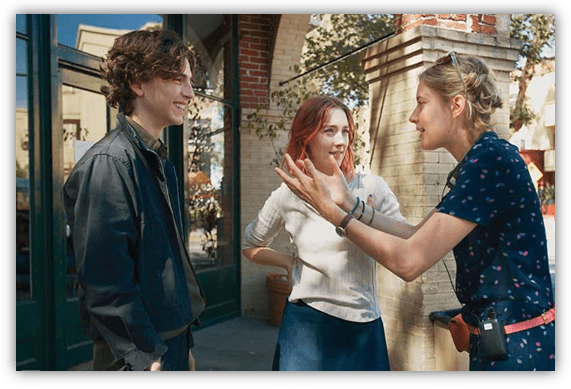

Jenna Walton (Odesa Rush), Immaculate Heart’s queen bee, casts a spell over Christine and Julie (Beanie Feldman), her BFF, as they spy on Jenna and her hive gathered around their leader’s SUV. Given the opportunity, unbeknownst to Julie, bonding over their shared jealousy of the popular girls, Christine would end their association in a heartbeat if Jenna showed the slightest interest in proffering an open invitation to her circle. The premeditated betrayal starts in earnest. Christine recognizes her opportunity for upward mobility, her golden ticket, sitting outside the café she waitresses at, nursing his coffee, engaged in a book, presumably thinking. It’s the boy Christine saw play bass at an all-ages show she identifies as an acolyte of Jenny’s. The name of Kyle’s band is L’enfance nue. It’s all that reading Kyle (Timothy Chamolet) does.

Show tunes, not indie rock, is what Gerwig employs to peg Christine as a misfit. She quits the school production of “Merrily We Roll Along”, passing along the torch to Julie without ceremony, making her sole keeper of the flame for Stephen Sondheim. “In Acquaintance to Natural Law”, all teenage girls want to be popular.

On prom night, Crash into Me plays over the radio, reminding the audience that Christine has bad taste in music.

Kyle hates Dave Matthews, which is just as well, since Christine hates Kyle for not coming to the house and going through “all that stupid old shit,” like meeting the folks and posing for pictures. Her thoughts return to Julie: ‘They’re putting down our song.’ Jenna decides she’s too cool for prom.

But Ladybird is not cool. Suddenly and belatedly, feeling like a poseur, she asks Kyle to let her out of the car. She takes Julie to the formal dance. Crash into Me is reprised, but this time it plays over the soundtrack, instead of transmitting from an in-frame source, the radio.

The song accompanies the prom montage, re-appropriated as an ode to friendship, taking its cues from Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha. It’s modern love, the notion that a best friend, not the person you’re dating or married to, can be the love of your life.

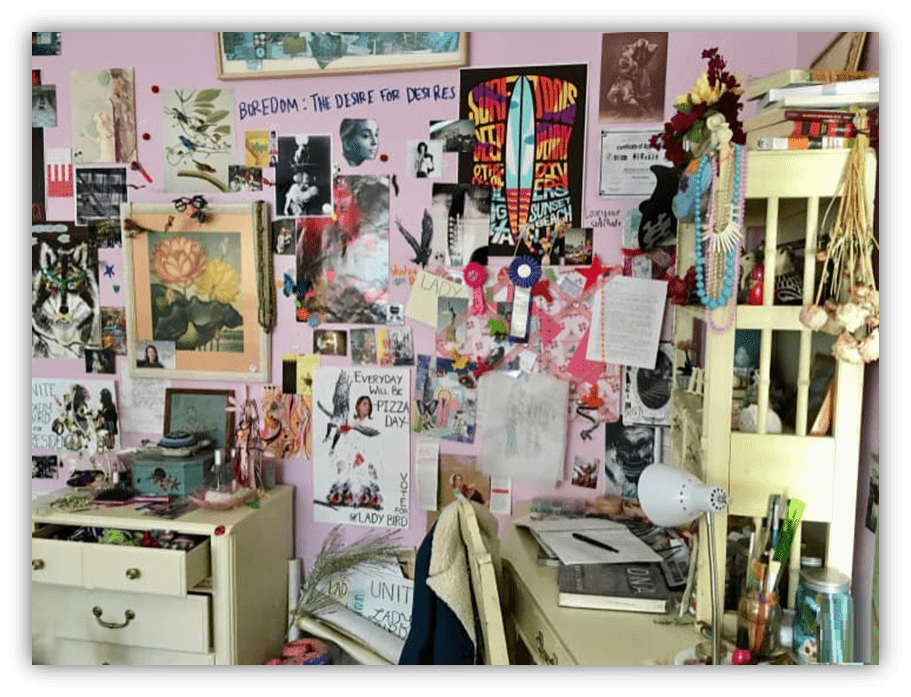

In Sixteen Candles, Samantha Baker (Molly Ringwald) sleeps under a Stray Cats poster. Sammy Hagar also graces the Baker household’s walls. If Gerwig possessed the extra-diegetic powers of intertextuality, an ability to astral project herself from film to film, she’d redecorate Samantha’s room, like a white and female version of Buggin’ Out in Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing, with X’s Exene Cervenka substituting for Malcolm X.

But Gerwig does. As the director, wielding her absolute power, she breaks down the fourth wall, late in Ladybird. If you search Christine’s bedroom, eventually your eyes land on reproductions of the cover art for Bikini Kill: The Singles and Sleater-Kinney’s Dig Me Out. That’s not her jams; she likes Dave Matthews, unironically. Crash Into Me makes her cry. The posters look like anachronisms.

They’re not. It’s the filmmaker as a girl’s bedroom.

These are Greta Gerwig’s posters.

What does Ladybird mean? Since Christine never offers an explanation, it’s translation is open for interpretation. In my opinion, it all comes back to John Hughes’ misuse of ‘pretty in pink.’ More than a nonsensical compound word, the alias operates as a cryptogram that restores and reaffirms Andy’s good name, three decades later. She’s a lady. “Bird” is New York slang for “promiscuous woman”, used by a particular type of New Yorker, a Brit. Richard Butler – what do you know – has been an Empire State resident for the past fifteen years.

Greta Gerwig owns the key to free all the exiles in Guyville.

Liz Phair sang a lot about sex at the outset of her career, which is now entering her third decade, and still does, although without the same precision that people associate from her early years. The sex that Phair expressed in her music was empowering, but more importantly, normal, and performed in 4/4 time like all inspired old school indie rock. F*** and Run was the exception; the album’s standout track could be Sexy +17 told from the woman’s point-of-view, in the context of the John Hughes industrial complex that Greta Gerwig challenges with raised fists. The crackerjack neo-rockabilly blast from the future past describes Andie Walsh as rendered in Brian Setzer’s rock and roll poetry.

Let’s break down each word:

- “stray” can mean promiscuous;

- “cat” has a long history of being associated with the woman.

- Stray cat means “promiscuous woman.”

Ladybird is a grrl bird. A canary.

I learn my name,

Canary, by Liz Phair

I write with a number two pencil

I work up to my potential

I earn my name.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “heart” upvote!

This is a home run. Thanks for covering so many topics I love, and making me need to see Ladybird!!!

Thank you, thegue. You can’t imagine what a frightening experience this is for me.

No need to worry, Great stuff. Like thegue I need to see Ladybird, its been on my watch list for a while but never quite get round to it. I’ve never seen Pretty In Pink either though I think I’ll keep that status.

Thank you, JJ Live at Leeds.

Great write-up, Cappie!

I myself have never heard any Liz Phair, nor have I seen anything by Greta Gerwig, but clearly John Hughes’ classic works are ripe for a cultural re-appraisal. Even Molly Ringwald agrees.

But Belinda Carlisle also needs a re-appraisal! She started out as the first drummer for the Germs, and even when recording sugary pop tunes with the Go-Gos, was living a life of scuzzy depravity to rival Pat Smear.

#DarbyCrashIntoMe

#JusticeForDMB

Thank you, Phylum of Alexandria.

This is going to get repetitive. I’m just grateful to anybody who took the time to read this. I’m used to writing in the anonymity of the IMDb.

Amazing post.

You have given me a lot to think about when it comes to this film. I enjoyed it when I first watched it and am looking forward to watching it again now.

I love how you connected Liz Phair to “Happy”.

Also, I never caught that “Crash” is played on the soundtrack in that scene. Mostly because I know nothing about film. 🙂 But it’s something like that which really had me wanting to watch this again.

As for John Hughes, I recently watched Uncle Buck on a lazy Sunday afternoon. Agreed. Has not aged well. There were a few scenes that made me wince.

A few years ago, a hip local hotel was doing a “dinner and movie” night where you could get some good food & drink and watch a movie poolside. The movie that weekend was “Uncle Buck”, which I didn’t remember seeing when I was younger. The wife & I said “How bad could it be?” Our kids were 11 and 9, and… oh, boy… We ended up turning it into a game where the kids could clap every time something inappropriate was shown / said, and many hands were red by the end of that experience.

First of all, thank you reading minor major 7th. Anything I write ends up in recent quippery, so maybe I should add something. I forgot to mention that “F & R” is the answer song to “Happy”. And I don’t think this was in my original draft. But Gerwig dramatizes the song when Christine has her first experience with Kyle(Timothy Chamolet). She’s the victim that Phair describes in the song. Christine decides she’s never going to be taken advantage again. In college, she’s the aggressor, inviting a random guy at a house party to her room, which is more in line with the other songs on “Exile in Guyville”. Thank you.

Great article!

I’ve been having a whole journey working through what to share from my kid / teen years as my kids move past a diet of animated movies, Harry Potter books, and top 40 music.

So much of it was (probably) well meaning at the time, but comes off as cringy or offensive now that I am forced to re-evaluate what might be artistically relevant to share, but will probably make the artist, and me for showing it, come off as out-of-touch dinosaurs. I have delivered many duds (for my kids) so far, but I’m not giving up exposing them to art that gets it 90-something percent right, and letting them know that things were not always created with inclusivity or sensitivity in mind.

I love what Gerwig did with “Ladybird” and I think that playing my boys “Exile From Guysville” might be more productive than showing them “16 Candles”

It’s a journey, and your writing echoes a lot of the inner conflict art and context has exposed to me as a parent. I’m working on breaking free of the need to shelter and trying to remember the rush of discovering art that’s “dangerous” without it engraving persistent negative attitudes into your world view.

Sorry – mega rambling, but this article definately got me thinking.

Oh, rambling is my writing style. In the original version, I was writing about a whole different movie, an unofficial remake of another John Hughes film. It’s good to have an editor. Thank you for reading, blu_cheez.

Bravo cappie, stellar debut!! Now, you do realize you’ve set the bar quite high for yourself from here on out?! 😉

Cappie, you took a bunch of things and people I love (Liz Phair, Greta Gerwig, Pretty in Pink, Bikini Kill, Lady Bird) and tied them together in a way I found perplexing. I still am trying to wrap my head around this and missing the boat.