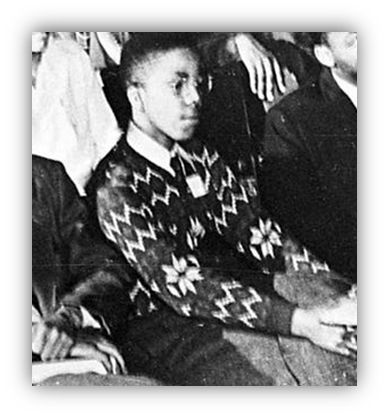

April 13, 1944. Atlanta, Georgia:

A 13-year-old boy and his teacher boarded a bus headed southeast, to Dublin. The boy was nervous but excited.

He was chosen to represent his school at a statewide competition in oration. As he sat by his teacher, the boy quietly mulled over his prepared lines, determined to get everything perfect.

At some point, he was ripped from the words of his speech to find that the bus driver was shouting at him. Two white passengers had boarded the bus, and the driver was telling him and his teacher to give up their seats. His teacher stood up immediately.

But the boy stayed put. He refused to move. He had just been reciting lines about how “Black America still wears chains. The finest Negro is at the mercy of the meanest white man. Even winners of our highest honors face the class color bar.” This line was to lead into how his esteemed teacher had previously been demeaned because of her color. Now this same woman was ordered to give up her seat and ride standing for several hours simply because of her darker skin?

The bus driver grew livid, calling the boy a “black son of a bitch.” For her part, Mrs. Anderson pleaded with her student to stand up and allow the other passengers to sit. She reminded him that he would be breaking the law if he remained seated.

Finally, the boy relented. He spent the rest of that long ride standing, seething with rage. He would soon win the statewide oratorical contest with the speech that he had written. But he realized to his deep dismay just how true his words had proven.

America’s rhetoric of freedom proved a crucial fuel for the continued expansion of that ideal. But how galling it must be to hear such rhetoric when it is so completely far from your own reality.

After the Civil War and its immediate aftermath, movement on black civil rights largely slowed to a halt until well into the 20th century.

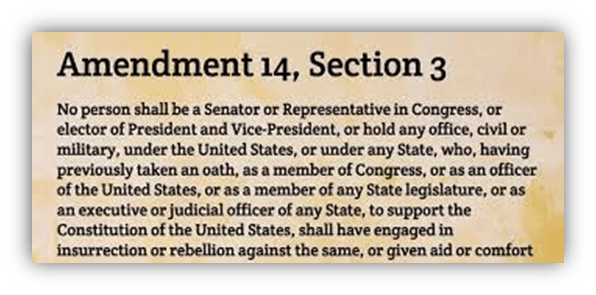

The 14th Amendment supposedly enshrined equal protection under the law. But actually enforcing that protection was another matter.

There was some progress in Northern states.

When Franklin Roosevelt enacted his New Deal policies, black workers often benefited from the increased focus on labor rights.

And the GI Bill of 1944 encouraged more black students to attend university, at least among those who had served in the military.

But those policies were broad in scope, and did not speak to the specific plight of black Americans.

More significant was in 1948, when Harry Truman ordered US military forces to be racially integrated. By the end of the Korean War, nearly every unit had been desegregated. That was tremendous progress.

Nevertheless, the national initiatives toward a liberal democratic order in the aftermath of WW2 couldn’t help but ring hollow on many fronts.

So long as Southern whites could continue their subjugation of black communities via state-enforced Jim Crow laws, all this talk of liberty was little more than pretty words.

The conundrum was as clear as day. White politicians in the south pushed laws that helped white communities and hindered black ones. Black men and women strove to vote for new representatives who could push new laws, but they were denied their right to vote. And anyone who protested this state of affairs was intimidated into silence, either by aggressive police or by vigilante terrorism. Sometimes those two were one and the same. Clearly, something had to give.

The first major push forward came from above. In late 1953, Dwight Eisenhower appointed Earl Warren as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, and in March 1954, he was confirmed by Congress. Just two months later, the Warren court would deliver an unprecedented blow to state-level discrimination: their decision on the case of Brown vs the Board of Education of Topeka, KS.

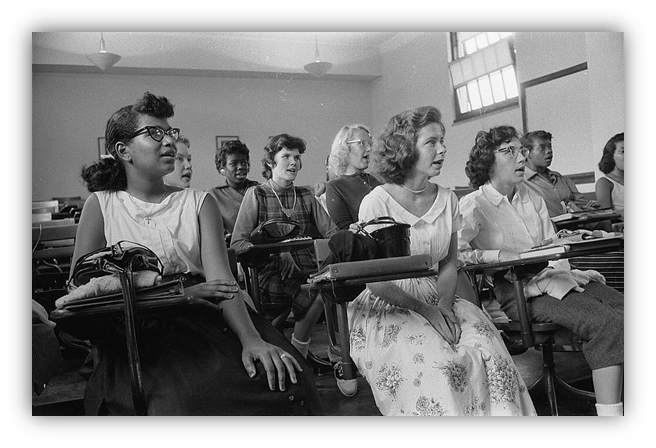

The court ruled unanimously that racially segregated school facilities were “inherently unequal.” This inequality was declared unconstitutional.

The Brown case was a huge victory for civil rights. Unfortunately, the ruling didn’t make it clear when or how such desegregation must take place. Southern governors privately declared the ruling illegitimate, and simply did nothing. Because of this, the decision did not lead to any immediate improvements on the ground.

But black communities were paying attention, especially the activists. If the push for social change could come from the bottom up, perhaps when a case reached the courts they would find some sympathetic ears.

But in the Jim Crow south, the threat of violence hung in the air. That threat was there for any black person who even so much as spoke out of turn. In this environment, collective action would come only after collective outrage.

It started with a murder in Money, Mississippi.

A black teen visiting from Chicago was dared by the local kids to sweet talk a white woman working the shop.

So the young Emmett Till entered the shop, paid for some candy, and then said “Bye, baby” as he turned and left.

Later that night, he was taken at gunpoint from his uncle’s house. A few days later, his uncle found a corpse floating naked in the river. Emmett’s face had been mutilated beyond recognition, but was wearing a necklace that identified him. The husband of the shop worker hadn’t liked how casually and confidently this black male had spoken to his wife. And for that, the 14-year-old youth was kidnapped, beaten, and brutally murdered.

This wasn’t the first lynching in America, nor was it the last. But the shock of Emmett Till’s death rang out among black communities all across the south. It also piqued the interest of news outlets from northern states.

Till’s mother insisted on an open casket funeral, so that everyone could see her son’s mutilated face. Some newspapers even printed the horrific image.

The trial was also widely televised. When the jury failed to convict Emmett Till’s murderers despite the two men admitting to his kidnapping, black communities around the nation were outraged. And this was the straw that broke the camel’s back. The spark that ignited everything else to come.

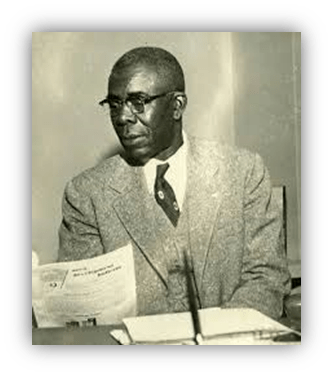

E.D. Nixon, president of the local NAACP chapter of Montgomery Alabama, sought to harness the anger and media attention surrounding the Till murder case in order to force the state toward their equal treatment under the law.

Nixon proposed that someone in their group remain seated in a public bus and refuse to move when asked. The arrest of this person would lead to a trial and controversy that activists could use to push the issue of bus segregation to the public spotlight.

The plan required someone who could dispel whatever vilifying spin the segregationists might use against them. Someone who could reach people on a human level. Nixon called upon a kind, soft-spoken woman, wife, and upright citizen who perfectly fit the bill.

This was Rosa Parks, who soon became a national icon for her courageous act of civil disobedience.

In response to Parks’ arrest and trial, E.D Nixon proposed a citywide boycott of the bus system by all black residents in Montgomery. This act would hit the city where it hurt, as black residents made up more than a third of its commuter base.

Notices were typed, copied, and distributed all around black neighborhoods to spread the word.

A vast volunteer network of car pickups was coordinated, but many more people walked great distances every day rather than use a bus.

The community remained steadfast, and they deprived Montgomery buses of their patronage for more than a year.

The boycott was E.D. Nixon’s idea, but he wasn’t the principal mover and shaker. Because his schedule prevented him from leading the effort beyond its first few days, Nixon had to find someone who could take his place.

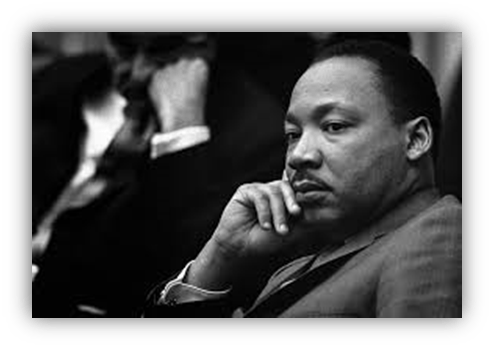

He decided upon a young minister who had recently moved to Montgomery. This man had just received his doctorate in theology from Boston University, but had been born and raised in Atlanta, GA.

As a 13-year-old boy, he had been forced to give up his seat on the bus ride to his proudest moment: winning a statewide oration contest.

That boy had grown into a gifted speaker, a scholar, and a respected minister.

And by leading Montgomery’s black community to protest their segregation on city buses, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. would begin to prove himself as one of the most consequential figures in civil rights history.

King and his followers made sure that the whole nation was aware of this new push for equal treatment.

He enlisted the talents of black celebrities such as Harry Belafonte and Sammy Davis Jr. to help raise awareness. And King himself grabbed the national spotlight. He not only demonstrated a gift for speeches but also a canny command of the media, with which he was able to steer public opinion in favor of their cause.

After more than a year of sustained collective effort, all while enduring verbal abuse, threats, arrests, and attempts to murder King and other leaders, the boycotters prevailed.

Alabama’s state court ruled that the segregation of buses was unconstitutional, and the Supreme Court upheld this decision.

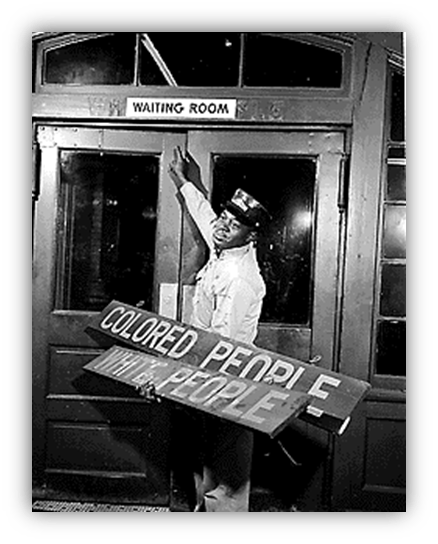

Montgomery and every other part of Alabama was forced to let black residents ride buses like everyone else. And indeed, the jubilant activists rode on the fronts of the buses in the days following the ruling, just to bask in the fact that they could.

This was a thrilling victory. But it was only the beginning.

There was still so much to do.

There were the local buses of every other Southern state to be desegregated.

Interstate buses and stations.

Department store lunch counters.

Elementary schools.

High schools. Colleges. Taxis.

And most important of all: the right for black citizens to vote, and to have their vote counted in the Jim Crow South.

And for all the effort and risks they had taken, the Montgomery boycotters had actually benefited from the element of surprise. In response to this first victory, the segregationists would be better prepared for all subsequent protests, and far more brutal in their reaction.

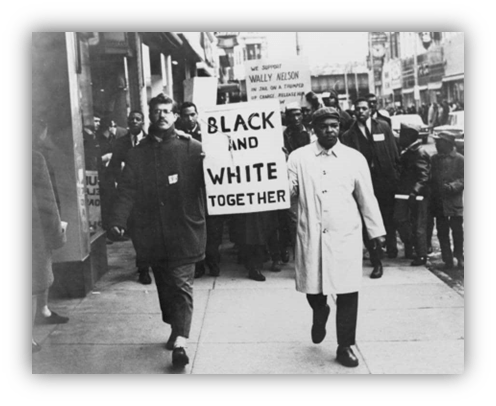

And still, the black communities assembled and mobilized. Soon enough joined by sympathetic whites, mostly from the North, but some younger Southerners too.

Together, these brave citizens charged ahead into fearsome uncertainty, using nonviolent protest tactics to push the country forward.

The rationale for nonviolent protest is ingenious and terribly cruel.

It works on the assumption that your opponents will humiliate and hurt you, possibly even try to kill you. Your job as the protestor is to accept that harm to your person willingly, even invite it. The challenge is to endure indignities and violence, to watch as others around you are beaten, or killed. And to do nothing in retaliation.

All this, in order to control the public narrative in your favor. To leave no question, no ambiguity, no room for argument with respect to who was the aggressor in a given confrontation, and who was the innocent victim.

And for their part, white men and women of the South embraced their roles as the aggressors with no qualms. The news footage from this time makes it perfectly clear how barbaric the white segregationists had been. Protestors in subsequent demonstrations faced prison. Brutal assaults. Riots. Lynchings. Attack dogs.

Fire hoses. Fire bombings. And shootings. Including King himself, who was assassinated in 1968.

But throughout it all, those communities stood together. Despite the threats and the brutality, despite the anger and the grief, they pushed ahead. Nowadays the notion of segregated buses or lunch counters seems so alien to us, even in Southern towns. That’s only because of the determination and tremendous sacrifice of those individuals fighting for equality. Together, they brought our nation, kicking and screaming, closer to its lofty ideal.

By the mid 1960s, federal laws were written to ensure equal protection under the law. All states were desegregated. Jim Crow was abolished. Nearly a hundred years after the end of slavery, black citizens finally became full participants in American democracy. Things were far from perfect even then. But the people had come together and brought our society up a little higher.

Of course, it’s hard to write about the civil rights movement without the story turning bleak, given the tragedy of King’s death, and many others.

But King himself would not suffer such despair, despite a sometimes grim reality with tremendous costs.

Here is the man himself, speaking right after the first attempt on his life, in 1956. Was he afraid? He responded:

“No, I am not.“

“My attitude is that this is a great cause, it is a great issue that we are confronted with. And that the consequences for my personal life are not particularly important. It is the triumph of a cause that I am concerned about.“

“And I have always felt that, ultimately, along the way of life, an individual must stand up and be counted, and be willing to face the consequences, whatever they are. And if he is filled with fear, he cannot do it.“

“My great prayer is always for God to save me from the paralysis of crippling fear.

Because I think when a person lives with the fears of the consequences for his personal life, he can never do anything in terms of lifting the whole of humanity, and solving many of the social problems which we confront in every age and every generation.”

King knew there was a long, hard road ahead. And he went along anyway. For his fellow brothers and sisters. For the greater good.

None of us know for sure what is in store for us in the roads ahead, along the way of life. We can only act in the moment, and hope that our actions will make some difference.

Should a similar moment of decision come, will you stand up and be counted?

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Great telling of an inspiring piece of history. I am strongly tempted to post the photo of Emmett Till, but I won’t. It punches you in the gut, and we all need that reminder from time to time that evil is real and we have to fight it with all our strength.

While I have my own opinions, I’m curious if we have consensus among us of what is / are the big fights we need to be fighting now. What’s our current moral crisis (or crises)?

Climate change, authoritarianism, income inequality, and anchovies on pizza.

I am pro anchovies all the way. A bit salty but so worth it.

Yep and maybe add in genocide to boot…

The more I read about Stephen Miller, the more I wonder. Project 2025 is hiding in plain sight. That’s where it was supposed to stay. But some elements of it crept into the Time interview. I am keeping a close eye on how the SC rules on immunity. After all, where I live, I’m surrounded by water. I’m not the Man from Atlantis. I can’t hop in a car and drive to Canada.

For me, climate change is the issue which will break society. Authoritarianism, the deterioration of democracy, the strangely flexible nature of truth, and on-court coaching in tennis are all topics which get me in a dander.

I’m neutral on the anchovy issue, but it ain’t pizza if it ain’t got pepperoni.

Thanks for the thought-provoking piece, Phylum. As we can see from the continuing efforts to curtail voting opportunities, this particular civil rights journey is still proceeding.

At the same time, as Pauly queries, others are abounding, and consensus about what to do is far from clear. I remain appalled that our Supreme Court has said it’s fine for someone to refuse to do business with me as long as their refusal is religiously grounded. What?

Anyhow, yes, we must stand up and be counted, regardless of whether we’re directly affected. Because, in the end, we’re always at least indirectly affected.

I wasn’t aware of 13-year-old MLK’s story but I should have been. It seems a pivotal moment in his development. He was on a path to greatness anyway, but that bus ride sums it up. Great storytelling, Phylum!

Didn’t expect something so inspirational this morning but you never know what you’ll get on TNOCS. One day it’s an uplifting call to arms like this. The next day, it’s a bracket challenge for the best yogurt flavor.

Hmmm. Maybe I’m on to something.

Phylum, I mentioned in your Waiting for Godot article that I was reading a book by Anne Lamott that appeared to be dovetailing a similar theme. It turned out a few chapters later that she actually referenced Waiting for Godot, which I thought was very interesting. Somebody somewhere is trying to tell me something?

I am a product of the Jim Crow South. I grew up in small-town Georgia, a child during the ’60s. I can remember the “whites only” signs and how the local movie theater was segregated, with whites on the floor and blacks on the balcony. I went to segregated schools through 5th grade.

I’d like to believe that I was enlightened and aware as a child, but let’s face it, I was just a dumb suburban kid living in a safe enclave. I know my parents were racists; my dad overtly, my mom of a gentler sort, but I have to give them credit for not forcing those beliefs (or any, for that matter) on me.

I can remember two particular incidents which impacted my beliefs, one of which had nothing to do with the civil rights struggle of African-Americans.

First, our school system was desegregated between my 5th and 6th grade years, something like 14 years after Brown. I moved from one school to another which were physically identical, both having been built during the separate but equal era on the same construction contract. Even my young eyes could see, however, that, while the buildings were built the same, no money had been spent on the upkeep of my new school, and that all of the school books were hand-me-downs. My previous school had always had books which were in good condition, and the building itself was renewed on a regular basis. As generally unaware as I was, even I could sense the inequity.

The other incident happened while we were on a great American family road trip out west. We were somewhere in Arizona or New Mexico (maybe along route 66) and had stopped for gasoline and snacks. While we were on our break I overheard a couple of men talking about what lousy so-and-sos injuns (Native Americans) are: filthy, stinking, lazy, etc. I remember thinking, wait a minute, indians are groovy, they star in movies and TV shows. Tonto is a hero. (My cultural understanding was not very nuanced.) This cannot be right, I thought, which led me to perhaps some glimmer of understanding about the civil rights movement and the inequalities in our society.

But have we made progress? Parts of the voting rights act are under assault, and certain segments of our society (I call them, ummmm, Republicans.) seem to believe that diversity and inclusion are bad things, and want to gerrymander democracy out of existence (or just over throw it, if needs be).

I may be getting simple minded as I enter my Medicare years, but somehow I don’t understand the country I call home. WTH happened.

There are many issues out there that deserve our attention and participation. Maybe not many that we would risk our lives for…but those “opportunities” may well come again if we’re not careful.

We all need a reminder like this. Thanks, Phylum.

We all probably need a little Mahalia as well.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=niNH9JZHiUc

Douglas Sirk might’ve been a pretty great guy. Mahalia Jackson is in Imitation of Life.

Whoah. I just played Mavis Staples’ Livin’ On a High Note just a couple of days ago. The M. Ward-produced album ends with “MLK Song”. (My favorite is the Laura Veirs’ contribution “History, Now”.) It’s hard to comprehend. Everything Dr. King accomplished is slowly being dismantled.

It’s been a crappy nine years for me. But it’s egotistical to make this about me. I’m upset on other people’s behalf. But am I doing anything, except complain? It’s a helpless feeling.

I know the feeling, we all feel it at least sometimes.

If you’re looking for something to do to help keep the Stephen Millers of the nation out of power, there are a few options here:

https://votesaveamerica.com/

You can donate time to canvassing or phone banking, or give money to key campaign efforts.

I am also going to work as an election officer. That’s less of a safe option depending on the area, but I’m guessing Honolulu would be fine. If you’re up for it, it’s a great way to engage with your local community. I did it during the pandemic, and it was really rewarding.

If we’re proactive, we can prevent the need for anything more drastic in the future!