So many new and important things were happening in the early years of the Cold War.

What were conservatives doing at the time? How fared the traditionalists in this emerging culture of freedom?

I’ve written previously about the rise of Christian fundamentalism against the churn of the modern world. By the 1930s, the fundamentalists had retreated out of the national spotlight. The term itself became less popular over time, with more communities opting for the more generic label “evangelical.”

Fundamentalism was still going strong in these years, just doing so on the margins.

In the privacy of their own churches, schools, radio shows, and revival tours, they were thriving, and they were expanding. But they were fragmented, and far from the levers of power.

They needed more than just a different name. They needed a total rebranding. What’s more, they needed a unifying movement to rally the nation for the glory of God.

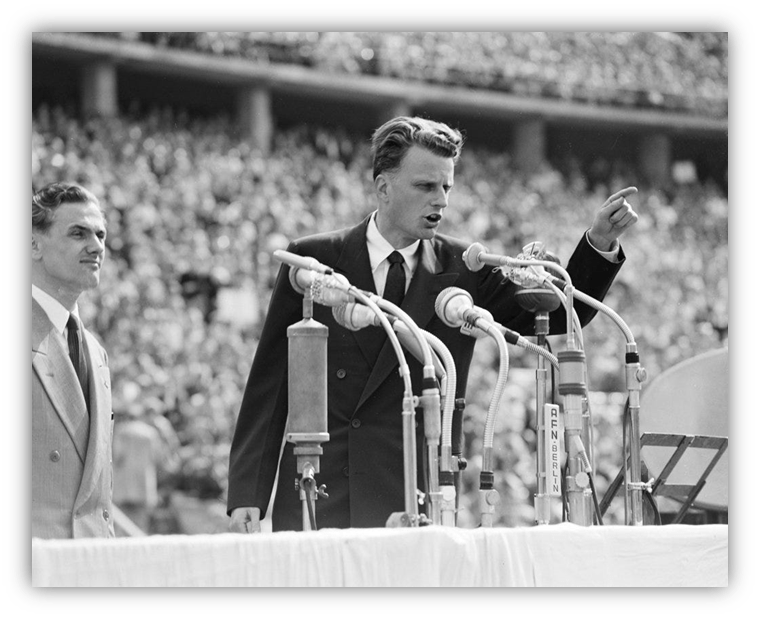

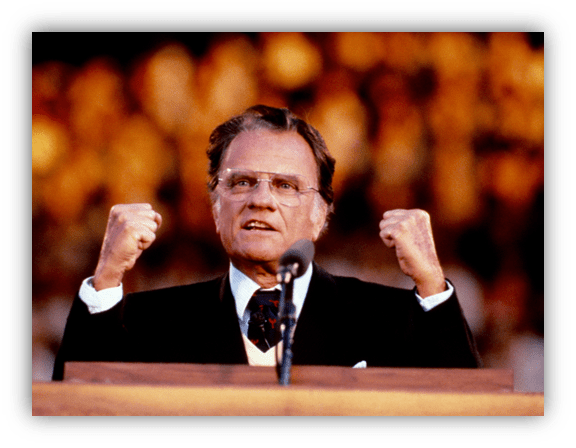

And then, in the late 1940s, something special happened. A charismatic young preacher began to grab headlines. This man held large revival events where he called on everyone willing to get up from their chairs to meet with him and get saved, just like Dwight Moody did in the 19th century.

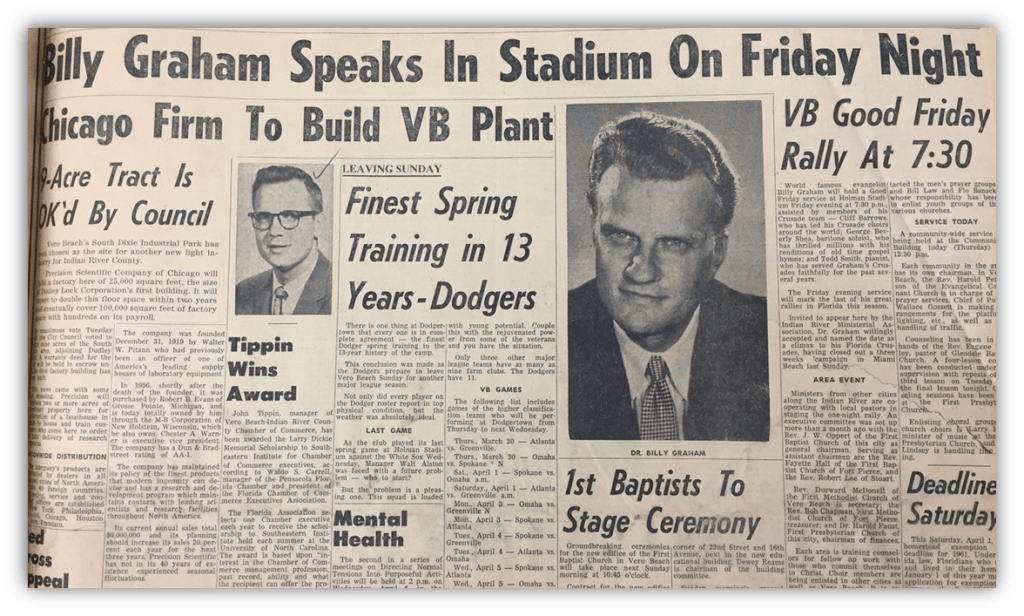

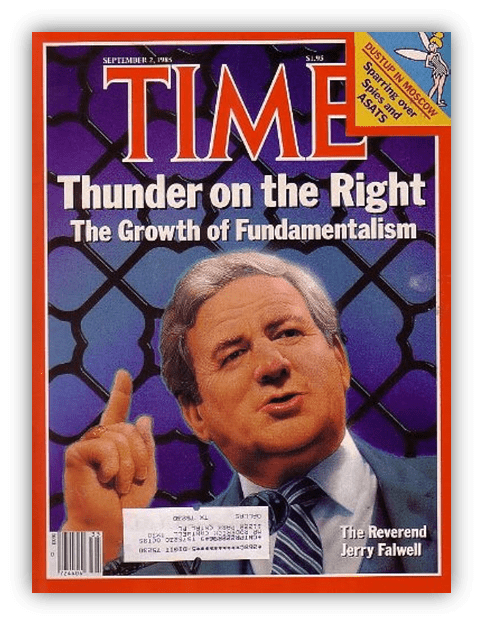

These events were the “crusades” of the Reverend Billy Graham.

Graham’s rise was in part due to some major promotional support from newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst.

Following the 1949 crusade in Los Angeles, Hearst sent a telegram to his editors: “Puff Graham.”

And from then on, the young preacher received glowing coverage in Hearst’s many papers, framing him as the next Billy Sunday.

By the early 1950s, he was a bona fide national celebrity.

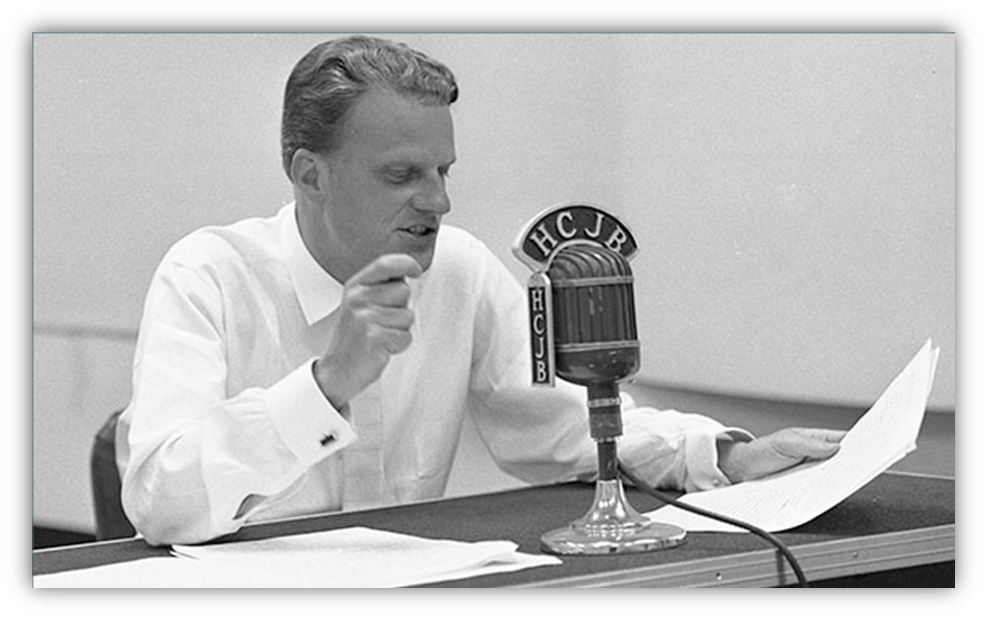

He hosted a weekly radio show, had his own newspaper and several magazines, formed his own film production team, and transmitted his crusades into homes across the country through the sensational new technology of television.

Graham’s message was for the most part a fundamentalist Christian one. Yet he was always at odds with the most conservative circles. His parents sent him to the ultra-traditional Bob Jones University, but he was nearly expelled for his carefree attitude. He finished his degree at the more moderately conservative Florida Bible Institute.

When Graham rose to national stardom, several fundamentalist institutions bestowed honorary degrees upon him, including Bob Jones University.

They looked upon this new icon to spread God’s word in their name. And as a minister, Graham preached the infallibility of the Christian bible, and of the rampant sins of the modern world.

His sermons had plenty of fire and brimstone, yet they were imbued with a patriotic spirit.

Graham sought to claim America for Christ, to make it a bulwark against Communism and other atheistic forces.

Accordingly, he preached the virtues of capitalism, and saw tyranny in socialist state management. His vision of Jesus was not meek or mild; it reflected the masculine stereotypes of the times:

“I’m not believing in some effeminate character. I’m believing in a real he-man, a real man who had a strong jaw and strong shoulders… Every inch a man! I believe in that Christ! I can follow that Christ!”

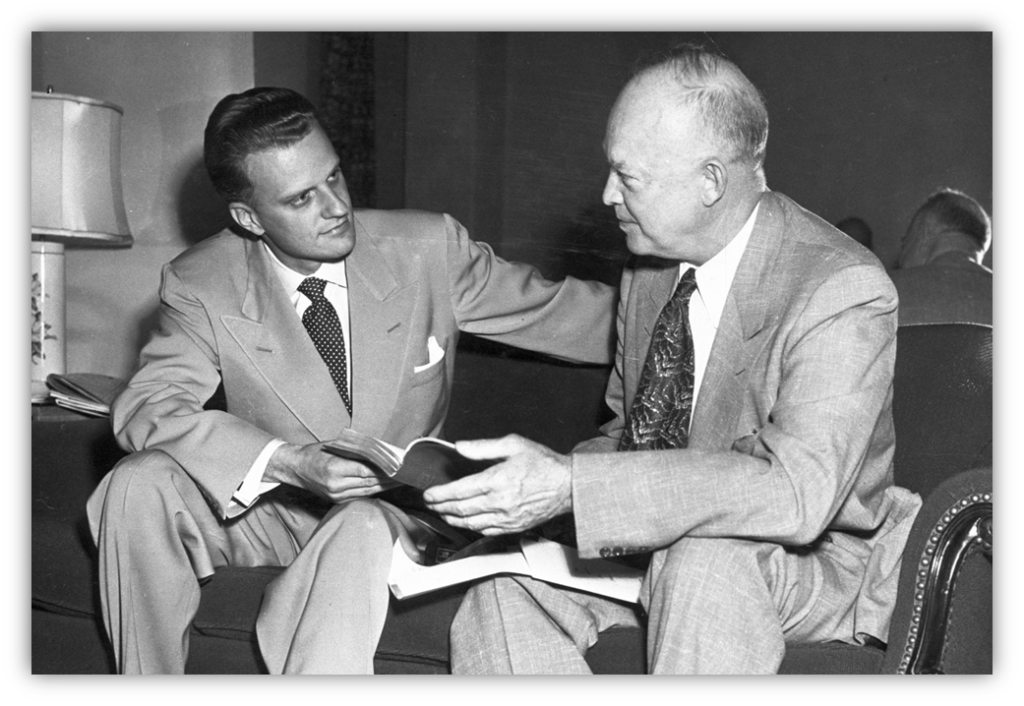

He was also the first person to serve as a spiritual counsel for the president of the United States.

Billy Graham met regularly with Dwight Eisenhower, and met with every subsequent president until his death.

Not to mention, Graham pushed Eisenhower to adopt “In God We Trust” as America’s national motto, and to add “under God” to the pledge of allegiance. Truly, this man was a force to be reckoned with.

American fundamentalists around this time were still divided as to the extent that they should meddle in political affairs.

For instance, in 1955, the theologian Francis Schaeffer founded his “l’Abri” community in rural Switzerland as a sacred retreat from the secular world. Graham’s hands-on approach to national affairs went a long way toward normalizing political activism among religious conservatives, at least over time.

Even so, Billy Graham’s moral vision was markedly more modern than most Christian fundamentalists.

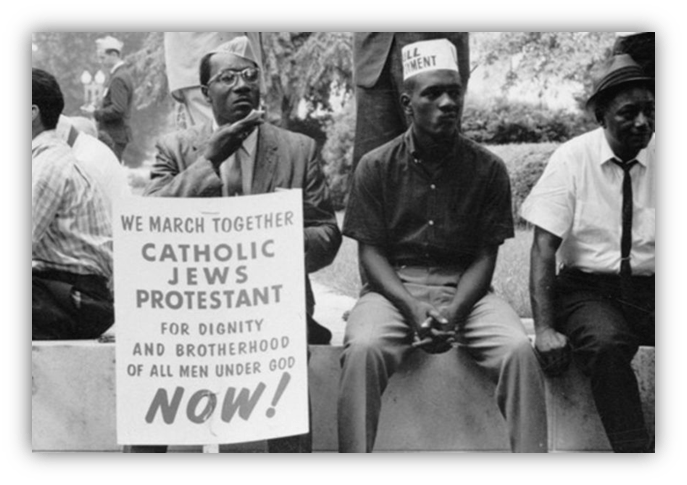

For instance, he was a white Southerner who spoke out against racial segregation. In 1953, at a Crusade rally in Chattanooga Tennessee, Graham knocked down the barriers separating black attendees from the rest of the audience.

To his shocked white congregants, he implored: “We have been proud, and thought we were better than any other race, any other people. Ladies and gentlemen, we are going to stumble into Hell because of our pride.”

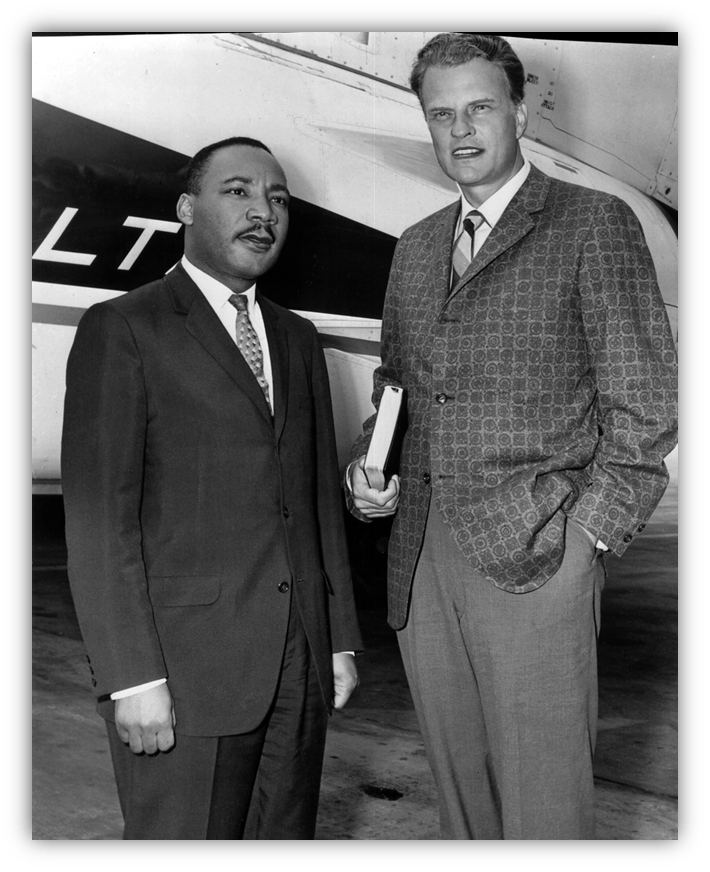

And in 1957, he invited liberal Christian leaders to his Crusade, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Conservatives were angered by this tolerant “ecumenical” stance, and they publicly rebuked the young reverend. For his part, Graham doubled down on a more inclusive approach to faith, eventually embracing Catholics and Jews as well. He wasn’t going to lose the battle for the soul of the nation by sweating the small stuff.

Graham has since been criticized for his reluctance to engage in civil rights advocacy beyond the desegregation of his Crusade events.

Though he and Dr. King became friends, they had several points of strong disagreement. When King implored that Graham not meet with segregationist politicians, Graham refused. And while Graham wanted to reform the system, he didn’t like the disruptive provocations of the civil rights protests.

He was still a conservative at heart, and so he sought reform that could respect the status quo. Unfortunately, as I touched on last time, that status quo could be extremely brutal to those on the outside.

Obviously, Dr. King’s cause feels righteous to us in hindsight, and Graham’s hesitation looks embarrassing by comparison. But we should approach such judgments with humility, as we may have our own moments of decision that are considered obviously wrong by folks looking back. Just ask Pete Seeger.

Billy Graham had his flaws and some major blind spots, perhaps most with respect to his rigid notion of masculinity. But he showed many times throughout his life that he could learn, grow, and adapt as the world around him changed.

Even when the changes of the world troubled him privately, he made sure his public demeanor nevertheless exemplified magnanimity and grace.

Lord knows that wasn’t true for other conservative leaders of the day. To the extent that they adapted, it was in horror to the changing world around them. And their public demeanor was by no means gracious. It was hostile and pugnacious.

The dawn of the Cold War ignited fears of communism that went far beyond the levels of someone like Billy Graham.

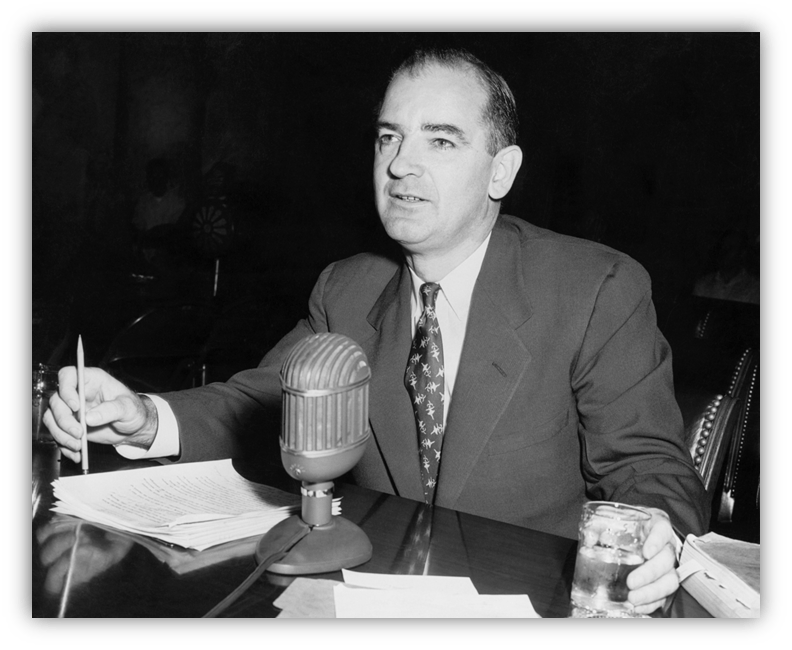

And when Joseph McCarthy rose to power via his televised interrogations of suspected communists, he fed into the most paranoid impulses of the American right.

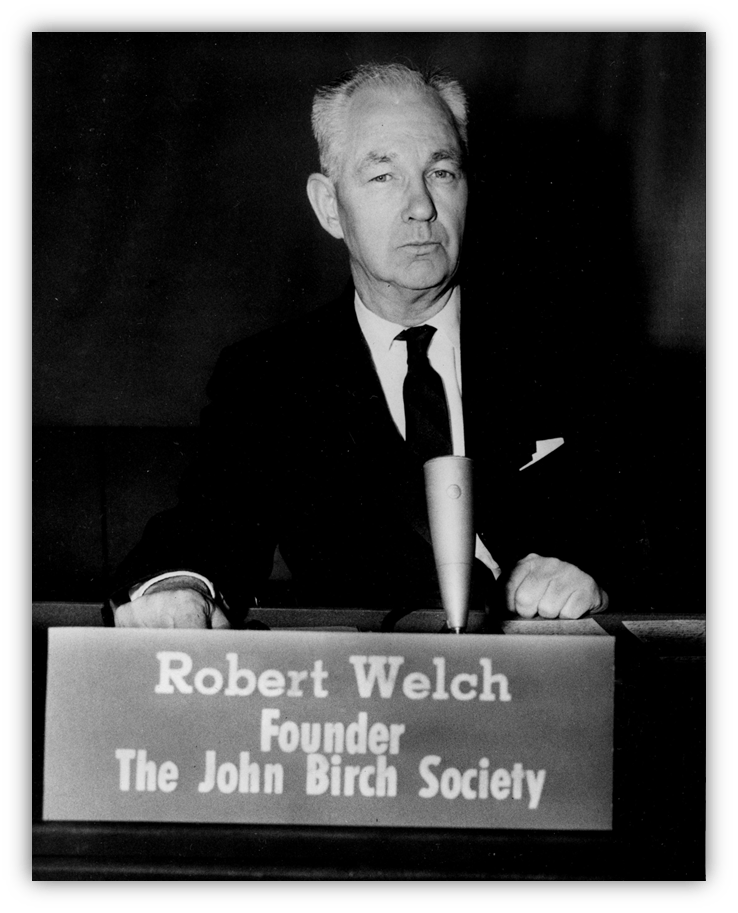

Beyond McCarthy himself, the worst of Red Scare paranoia came from Robert Welch, Jr.

Originally the creator of the Sugar Daddy and Junior Mint candy, Welch joined with other like minded businessmen to found the John Birch Society in 1958. This was a political advocacy group that pumped extreme far right views and wild conspiracy theories into public awareness via grassroots networking and publications.

Welch and his group alleged that President Eisenhower was a secret puppet of Russia, and that fluoride in America’s drinking water was a communist plot to infiltrate American minds. Gen. Jack D. Ripper from Dr. Strangelove would have felt right at home as a Bircher.

Of course, the supposed insider threat wasn’t always coordinated by Russia. The fundamentalist theologian R.J. Rushdoony was cultivating his stance on Christian Dominionism around this time.

This was the belief that Christians needed to seize the reins of governmental and cultural power, and force the nation back to pre-modern notions of God, knowledge, and humanity.

The boom of American home schooling among fundamentalists began with Rushdoony’s calls for communities of faith to escape contamination from secular influence.

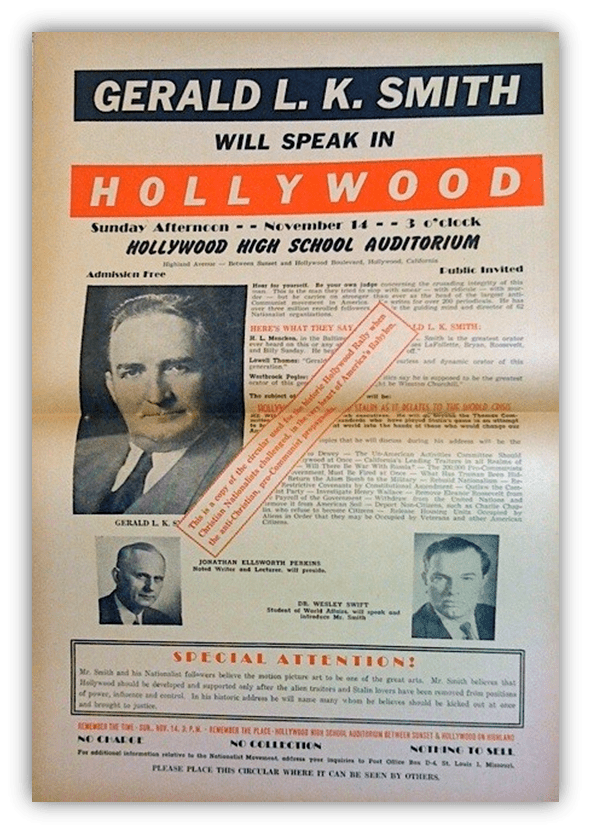

But that was small potatoes compared to Gerald L. K. Smith, founder of the America First Party, and then the Christian Nationalist Party.

An admirer of Hitler, Smith advocated for the deportation of black and Jewish Americans from the US. He advanced the conspiracy theory that six million jews did not die in the Holocaust; instead, they infiltrated the United States as immigrants.

Sadly, Smith’s ideas did not remain on the fringe, and Christian Nationalism lives on. Most Christian leaders did not go as far as Smith did, but the outbreak of civil rights activism beginning in the mid 50s served to galvanize white evangelicals into political engagement like no other issue had before.

In 1956, Reverend Jerry Falwell started a nationally broadcasted radio and television program, “The Old Time Gospel Hour.” The young preacher rose to prominence riding a wave of anger at the outbreak of disruptive protest and civil disobedience.

But Falwell’s early sermons focused less on social disruption and more on the supposed dangers of racial integration. He later founded the Lynchburg Christian Academy as a sanctuary of sorts for white students to avoid desegregated public schools.

Over the years, though, he shifted his rhetoric away from explicit racial content to one of individual freedom versus government meddling. Hence the name of his most famous institution, Liberty University.

Falwell’s canny shift into the language of liberty fell in line with a larger transformation among American conservatives that had started in the 1940s, and exploded in the late 60s. In reaction to federal executives and judiciaries insisting on expanding the rights of others, the social authoritarians found common cause with people who chafed at any type of government restrictions on their businesses: the libertarians.

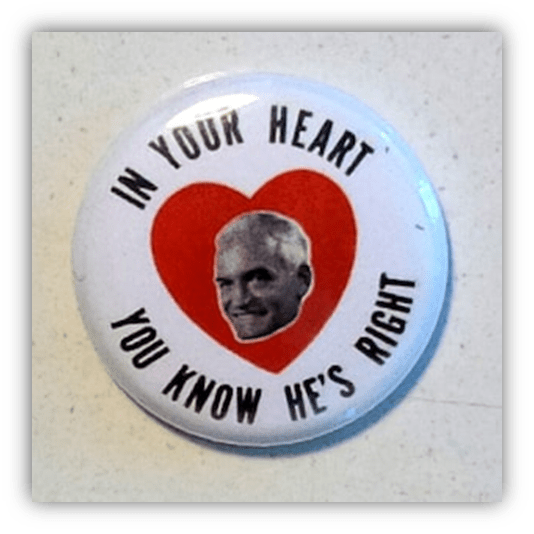

Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign was one of the major catalysts for this nationwide political transformation.

Goldwater attacked New Deal economic policies as well as recent civil rights legislation, on the grounds that the federal government should not limit the power of state and local government.

While Goldwater lost the ’64 election, his campaign would prove highly influential in elections to come.

His 1960 book, The Conscience of a Conservative, laid out the blueprint for this modern type of conservatism: staunchly anti-communist, opposed to business regulations and unions, honoring religious traditions, and demanding decentralized government for greater local power.

Notably, Goldwater’s book was ghostwritten by L. Brent Bozell Jr. of The National Review. Bozell and his brother-in-law William F. Buckley Jr. could in many respects be seen as the grand architects of this modern conservatism, stitching together multiple strands of thought in order to create a new conservative coalition.

But, in truth, the vision for America that the National Review advanced was very close to what Billy Graham had been preaching since the late 1940s. They had very different styles to them: Buckley could be rather pugnacious and combative towards his liberal opponents, while Graham tended to be gracious0.

Of course, that was likely more to do with Graham’s concept of himself as a non-partisan public figure than any deep political disagreement with Buckley.

Certainly Graham had made some ugly statements in contexts he assumed were private. Whether this case reflected his lying to donors he hated or pandering to a paranoid president, it’s clear that the national spotlight introduced some dangerous temptations to threaten his values, and he could not always resist.

Yet I don’t want to sell Graham’s public persona short, as if he was just faking it while the rest of the conservative leaders were keeping it real. They were all faking it to some extent. They all adopted a certain face to show the world.

But it was Billy Graham who fashioned a public self that was generous and magnanimous. Me

Meanwhile, William Buckley, Jerry Falwell, and countless other conservatives chose to make public personas centered on resentment, animus, and theatrical opposition to at least half of the nation.

To me, that is the crucial difference that sets Graham apart from the rest.

Graham not only modernized Christian fundamentalism, he laid the groundwork for a viable conservative movement in post-war America.

Crucially though, while Graham remained popular and deeply respected among conservatives all across the nation, the movement largely turned to different leaders for guidance on how to see Americans with whom they disagreed. Without thinking too much about it, they forsook the path of grace, and set down the path of revenge.

If you go back far enough into the history books, even progressive radicals of the past will look retrograde to us, so the conservatives really have no hope in that respect. Still, we shouldn’t minimize the importance of people being concerned with community, stability, connection to tradition, and having an air of caution about drastic reforms.

Think of the near-magical resolve of the civil rights protestors.

That collective resolve largely came from community connections. Community support. Community expectations. And community religion.

Liberalism and modernity aren’t always a threat to community, but they easily can be. Conservatism shouldn’t be a dirty word.

As our world changes ever more rapidly and dramatically, there will be those who bristle and wrestle with those developments more than others. I for one would rather have a conservative movement shaped by leaders who embrace a positive vision of the nation than those who look back to some mythic past.

I’d rather have people preaching prudence rather than pushing for radical action. I’d rather have criticisms delivered in good faith, and with an air of respect.

Hey, I can dream, right?

Billy Graham was neither a saint nor a miracle worker. But he was an exemplary man, and a significant positive influence on the nation.

If only the conservatives today would listen to their better angels and follow his example.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

We called them WFAs–white flight academies. They sprung up like mushrooms around Georgia (and probably other Southern states) in the very early ’70s as school desegregation took hold. I know most of the counties in my part of Georgia had (have) one.

It’s funny, but in my mind I’ve somehow always conflated Billy Graham (How tall was that guy?) with Paul Harvey, as though they were the same person. They would, no doubt, have objected.

And now you know the rest of the story.

I recently watched the Netflix series on Jeffrey Dahmer, and noticed that someone used the term “segs” to refer to those schools. I like that one because it sounds more self-evidently derogatory.

I can see the resemblance between Graham and Harvey. I’m pretty sure my wife would confuse them, as she’s not so specialized in the nuances of Caucasian faces.

I confused Graham and Harvey, too! I guess they looked alike.

Our governor here in Tennessee is pushing a school voucher program so parents can use taxpayer dollars to send their children to private schools. His public reasoning is that good parents want their kids to good schools. When it’s suggested that those dollars could be used to improve the public schools, well, he just sort of dodges the question.

I was glad that bill was stymied this session, but I’m sure that it will raise its ugly head again soon.

We now have this in Ohio. It’s amazing how high your household income has to be for the state NOT to pay for your kids’ private schooling. It’s just weird.

Always a fascinating topic for me when religion and its importance and influence in the US comes up. I remember Billy Graham coming over here on his crusades. He visited many times from the 50s to the end of the 80s with millions attending. With that many people seeing him he must have had some influence and there is an evangelical movement but overall church attendance continues to decline from an already small base and outside of a committed minority the country drifts ever more to secularism.

It means that religion isn’t used in the same way as a political tool. Though I see similarities in the methods you describe, its the same issues but framed outside of religion. The exception being in using Islamophobia as a signifier of ‘otherness’ and to promote fear and difference.

It’s a small but vocal and often wealthily backed miscreants that shout loudest to create headlines and try to convince the rest of their cause. The Archbishop of Canterbury is head of the (Anglican) church and generally comes from a left wing area of tolerance and understanding but that doesn’t generate headlines. And on the occasions he does gets pushback from right wing shouters that he shouldn’t involve himself in politics.

With or without religion in the mix the takeaway message remains relevant. Listen and understand instead of dictating and harking back to a mythic rose tinted era.

Genuinely surprised to learn that In God We Trust only dates from Eisnehower. I had assumed it went all the way back to the founding fathers.

I didn’t mention in the post, but I attended a Billy Graham crusade as a kid, in 1992. It was at Philly’s baseball stadium, and I went down on the field to accept Jesus Christ as my Lord and Savior.

It couldn’t withstand the pull of adolescence, but I look back fondly on the experience.

The most influential of the founding fathers were deists, but were profoundly suspicious of religion as most people practiced it. Jefferson and Franklin likely would have been appalled at such explicit mingling of church and state–and so am I, to some extent.

But I understand where Eisenhower was coming from. It was largely a numbers game to get people on board with the new national programs. It was probably a net win, though there are always drawbacks.

I have trouble in thinking of conservatism as not a dirty word. I feel it’s been ineradicably stained by regressive policies, fundamentalist Christian dogma, a blinkered belief in American exceptionalism, and a basic opposition to change. It’s damaging, schismatic, and close-minded, whether coming from the mouth of an otherwise pious and philanthropic person of the cloth, or a fire-breathing politician. Morally and humanistically, I cannot abide.

I share those sentiments sometimes. We could probably say the same thing about “patriotism” in America. But I’d much rather have thoughtful people claim the notion for themselves and breathe new life into it, rather than let the jerks define it.

There is such a thing as principled conservatism. Even if a lot of people who self-identify as conservative have drifted far away from it, there are others who are out there, and they need to step up and claim that mantle.

“ There is such a thing as principled conservatism.”

While I have absolutely no doubt, I am hard pressed to think of an example of a current self-described conservative demonstrating such actions or behavior.

They’re out there, I swear. The perspectives of David Frum, David French, Charlie Sykes, The Bulwark, and (sometimes) Ross Douthat are worth seeking out.

But I was thinking more about regular folks out there who tend not to engage much in public discussions.

Second paragraph: I agree with this. The average American, I think, does not follow the news cycle at all. “Guardrails” and “check and balances” aren’t a part of their everyday vocabulary; it’s an unnamed sensibility that whatever problems there are will self-correct itself.

Jerry Falwell. I know stuff about him. Too intense. I’ll just throw the name Jimmy Carter out there.

If you feel the need to add a modifier to your political affiliation like ‘principled’ or ‘compassionate,’ you’re admitting that there’s a majority of your affiliation who are not ‘principled’ or ‘compassionate.’ I’m of the opinion that the bedrock beliefs of the conservative movement can’t help but birth things like opposition to desegragation or a slide toward authoritarianism.

I don’t think authoritarianism is inevitable, but I agree that it is the central risk of conservatism.

I also won’t argue against the notion that one side is currently in a much, much worse state than the other. That’s a tragically unavoidable fact. But I also don’t like to think of my own side as inevitably good, or free from our own pitfalls. We’ve got different risks and different blind spots to account for.

If someone happens to be principled, and willing to treat me like a fellow human being, I will commend them and try to work with them.

Or as the Jesus of Mark (and not Matthew) said: “He who is not against me is with me.” Live and let live, as long as they do the same.

I do want to thank Phylum for his thought-provoking column. I hope my stridency concerning all this hasn’t put anyone off. Our discussions here are always informative, entertaining, and respectful.

Thanks! Always a pleasure!

stobgopper, we would never want to be without you.

From personal experience and exposure, I always had a general understanding that the evangelical movement into politics really rose to prominence in the 80s, but your thorough dive into its roots tells me that the seeds were sown long before that. Really interesting stuff, some of which I was aware, much I was not.

I never attended a Billy Graham crusade, but I did win his book How to Be Born Again in a raffle at a Christian Book Store when I was in high school, and gave it to my father. Nothing subtle in that gesture at all.

About the only good thing I can say about Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority is that without it, we would likely not have Mr Roboto, which Dennis DeYoung wrote in response to that group’s political and moral crusade.

Yeah, the late 70s into the 80s was the culmination of things that had been stirring for some time. The “Moral Majority” era was when they went into overdrive. Maybe I’ll get there some day.

I had no idea that Mr. Roboto was satirizing Falwell.

どうもありがとう、ミスターローラーブギー!

The “plot” of the song is that Kilroy, a rock and roll singer (played by Dennis DeYoung) is sent to a prison for rock and roll misfits by the the Majority for Musical Morality and its founder Dr. Everett Righteous (played by James Young)

Good point, rb! Conservatives are good for spawning excellent rebuttals.

The 80s are a goldmine in that respect.

Ooh. If the Moral Majority is in any way responsible for “Mr. Roboto,” that is by far its biggest sin.

😪

There was a time when I voted for the occasional conservative Republican (Richard Lugar, for one, in my Hoosier days). I suspect Lugar today would not be considered conservative.

I’ve always thought of myself as moderate but am sure that my orientation would automatically render me liberal or further left to a significant chunk of today’s GOP.

Graham’s quote on Christ makes me think he’s got Superman and Jesus mixed up in his imagination. But then I guess it’s that vision that led a generation to Mel Gibson’s take …

Great piece today, Phylum.

Billy was tapping into an earlier tradition with the manly Jesus thing, but it only dates back to late 19th century US and England.

Nowadays, even that athletic Jesus was too lithe. We need to get with the times!

I really liked this article, Phylum. My experience being raised religious was not very radical and involved zero television evangelists. While I realize that some were better than others, and that some were a great inspiration to many, I always felt a phony vibe from them. But even in my perception, Billy Graham seemed more respectable, though I knew little about them.

As a lifelong Christian and conservative, I find myself being drawn more and more to the middle and even to the liberal side on many topics, a place that I never suspected I would be. It’s a little bit of a struggle as I don’t want to be pulled away from by Christian beliefs. (Wait…the conservative Christians were wrong about segregation only decades ago…were they also wrong about Christ?) Well, that may be an understandable query, but I’m not going to throw out the baby with the bathwater.

I suppose I have worried about whether I was conservative enough for Christ, but as I age I am much more drawn to those for whom their love for Christ and his teachings motivate them to do good in the world, be empathetic, and be meek. I am also inspired by non-Christians that do the same. There are plenty of good, Christian liberals out there. They might not be radical liberals, but they sure wouldn’t fit in with the Rush Limbaugh crowd.

I have written a lot of words and erased them over and over again. I care about this topic, but my writing is insufficient for expressing my feelings. But just the fact that you’re stirring up feelings means that you have succeeded Phylum and other commenters. Thanks everyone.

Thanks Link. We need more good faith conservative perspectives to keep us libs sharp.

While I’d love to say that I have a grand theory that each chapter of this series is building toward, the truth is that each entry I write helps me stew on the larger issues a little more, helping me work through the impossible task of understanding and learning from the past, just a tiny bit.

So, I’m working through stirred feelings just as you are. We shouldn’t pretend that this stuff is easy, because it’s not.

For all of us, though maybe especially for people of faith, the philosophy of Soren Kierkegaard seems especially relevant these days. There are no easy answers, and faith is hard. Free will is our greatest gift, and our gravest responsibility. And given that our actions will define us, we should never forget the importance of learning, of redemption, and of grace.

But, we also need some levity. So bring on the music posts!