“Every expansion of a civilized power is a conquest for peace. It means not only the extension of American influence and power, it means the extension of liberty and order, and the bringing nearer by gigantic strides of the day when peace shall come to the whole earth.”

–Theodore Roosevelt, 1899

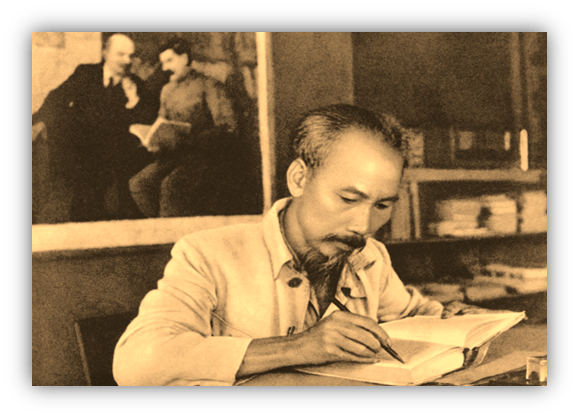

On May 19, 1890, in the village of Kim Lien in central Vietnam, a son was born in the household of a Confucian scholar. The boy was named Nguyen Sinh Cung.

At this time, the territories of Indochina had been under French subjugation for several decades, based on the export of rice and the manufacturing of rubber. The French’s treatment of the land and its native people could be brutal.

Cung was raised in relative wealth, and did not lack for education or opportunity. Following Confucian tradition, he received a new name at age ten. He was then Nguyen Tat Than, the given name meaning: “the accomplished.”

His first taste of rebellion came in 1908. He witnessed a crowd of villagers protesting against the French for corruption and high taxation. Than was a young man then, and while later stories suggest he took part in the protest, the risk would have been too great for his future prospects. Instead, he enrolled in an esteemed college and began his studies there. The protest had set off a spark within him, but that spark would take time to grow and spread.

Soon after graduating college, Than traveled the world, working as a kitchen hand on steam boats. After traveling to France, he visited Harlem and Boston in the US. He also worked for a few years as a pastry chef in Westminster, London.

Then in 1919, he set out for Paris, hoping to become more politically engaged.

There he joined The Group of Vietnamese Patriots, working tirelessly for the independence of Vietnam from French rule. To protect his reputation, he adopted a pseudonym: Nguyen Ai Quoc.

Quoc and his group wrote letters to national leaders to plead for their cause at a coming conference at Versailles following the close of World War I. Alas, President Woodrow Wilson and others did not reply, and the issue of Indochina remained unaddressed at the conference.

This was only a few years after the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, and communist sentiment was bubbling throughout Paris. Quoc soon adopted communism as his guiding ideology to understand the political world. He visited Moscow, and stayed for a time in China, Taiwan, Thailand, and India.

During this period, he worked for the Soviet organization Communist International. Yet Nyugen Ai Quoc considered himself a Vietnamese nationalist first, and a communist second.

He strove to forge an international network of Vietnamese ex-patriots, and he founded the Indochinese Communist Party. Though initially raised by a scholar, these recent years of study had trained Quoc to become a man of action.

“War is a racket. It always has been. It is possibly the oldest, easily the most profitable, surely the most vicious. It is the only one international in scope. It is the only one in which the profits are reckoned in dollars and the losses in lives.”

–Retired Major General Smedley D. Butler, 1935

When France came under occupation in 1940, the Nazis offered their Indochina colony to Japan. Soon Japanese imperial troops flooded the lands of Vietnam, seizing rice and rubber stocks to replenish their armies abroad. They were even more brutal than the French had been, and their rice exports instigated mass starvation and death among the Vietnamese

Even so, Nguyen Ai Quoc saw this transitional period as the perfect opportunity to start his revolution.

He returned to his homeland in 1943, and quickly began to coordinate guerilla combat actions against the Japanese. Many Vietnamese people, fed up with foreign occupation, flocked to his cause.

Unlike their enemies, Quoc and his rebel fighters knew the terrain well. They could do major damage without being seen. They eventually received weapons and combat training from the United States Office of Strategic Services, in the interest of speeding up Japan’s defeat and surrender.

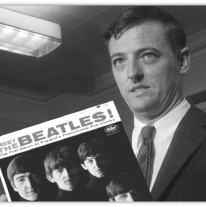

It was during this first resistance that Quoc had christened himself with a new name, one we all know and recognize.

He was now Ho Chi Minh. Bringer of Light, or He Who Enlightens. And his new band of rebels was dubbed the Viet Minh.

In 1945, Japan surrendered to the Allied Nations. The man they had installed as emperor to Vietnam had abdicated. Soon the US and the United Nations would vow to end colonial rule across the world.

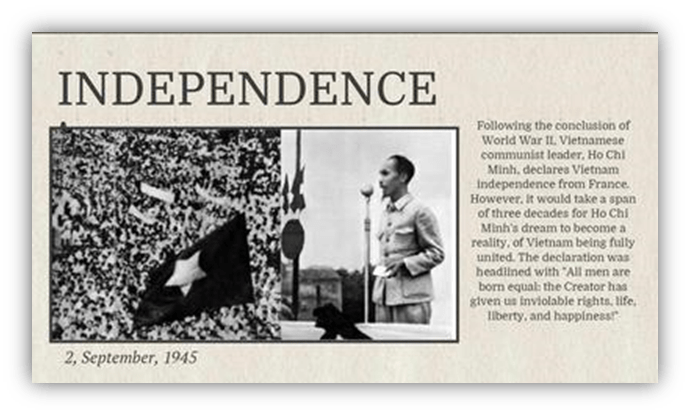

In Ba Dinh Square in the city of Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh proclaimed the independence of Vietnam from foreign occupation.

He read aloud a newly drafted Declaration of Independence for the sovereign nation, one that liberally quoted the words Thomas Jefferson had penned for American independence. And the crowd exulted.

…After which the French promptly reclaimed their territory. With help from England. And with silence from the US.

The new alliance against Russia being too important to jeopardize, one of their first acts was to sanction the very imperialism they had vowed to eradicate.

Surely that decision wouldn’t have any real consequences going forward, would it?

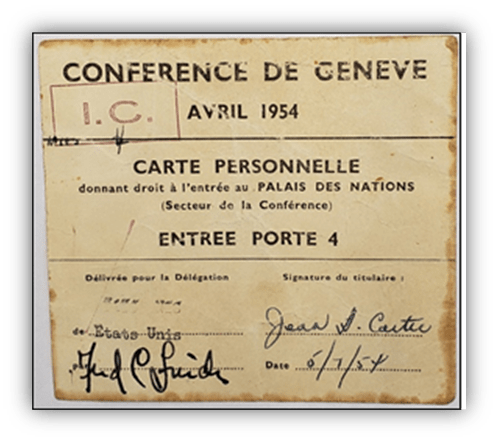

Cut to June 1954. After eight years of fighting against the Viet Minh army, and a devastating battle at Dien Ben Phu, the French forces retreated and evacuated northern Vietnam.

At the Geneva Convention that year, it was agreed that a border separating the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the north and the State of Vietnam in the south be recognized.

The stated intention was that the border be temporary, until elections were held to determine who would lead a unified nation of Vietnam.

But those elections were never held. This was because the US and its allies did not want Ho Chi Minh to win the election and have Vietnam become a communist nation. And so they stalled. And stalled.

Eventually, communist forces in southern Vietnam began to attack the French-sympathetic leadership in Saigon. And the Viet Minh began to attack as well, gathering more forces from nearby Laos.

This new collective resistance was called the National Liberation Front of Southern Vietnam. Soon to be dubbed the “Viet Cong.”

Thus the end of the first Indochina war led right into what we call The Vietnam War.

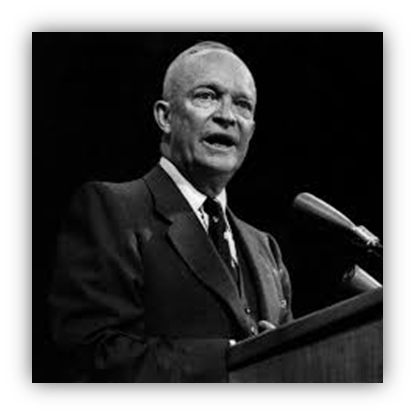

“It is my personal conviction that almost any one of the newborn states of the world would far rather embrace Communism or any other form of dictatorship than acknowledge the political domination of another government, even though that brought to each citizen a far higher standard of living.”

–Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1956

China had fallen to communist rule in the late 1940s under Mao Zedong. Then Czechoslovakia, and Hungary fell to the Soviets.

Korea had erupted into war and ended in a stalemate between communist north and anti-communist south. And it looked like Vietnam was on the same track.

The US had already poured billions of dollars into its support for France’s fight against the Viet Minh. But the conflict between North and South Vietnam took on new significance to President Eisenhower. He saw it as a potential pivot point in the global cold war against the communists.

He was the first president to send US troops into Vietnam to fight the Viet Cong. He was not the last.

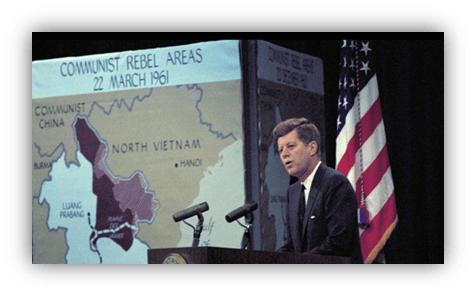

Kennedy increased our military presence in Vietnam.

Kennedy had special sympathy for Ngo Dinh Diem, president of the southern Republic of Vietnam, and a fellow Catholic and staunch anti-communist.

Unfortunately, awfulness knew no sides in Vietnam.

Diem imposed policies that highly favored the nation’s Catholic minority, and discriminated against the Buddhists and Taoists there. When a ban on religious flags led to a protest by Buddhists, Diem sent forces to silence them, leading to several protestors killed by grenades. Diem blamed the murders on the Viet Cong, which further angered the people, which led to his troops gassing and burning more protesters.

His actions led to the now-iconic image of a Buddhist monk setting himself on fire in protest.

For the first time ever in history, the minute details of a war were televised and watched by audiences around the world.

The self-immolation of Thic Quang Durc was not a winning message for Diem’s Western allies. And so, Diem was assassinated in a coup d’etat that was backed by the CIA.

Just a few weeks later, Kennedy himself was assassinated.

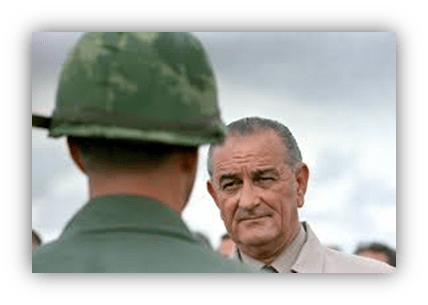

His vice president, Lyndon Johnson assumed the presidency. And it was during this term that the United States really ramped up its war in Vietnam.

After several US destroyer boats had been attacked on the Gulf of Tonkin by Viet Cong, Lyndon announced a dramatic escalation in military troops sent there to fight.

Johnson knew the stakes and the risks of such an endeavor, but he was determined to nip this problem in the bud.

But no matter the number of soldiers or the weapons used, the terms of this war were not in their favor. The Americans did not know the land, and they didn’t know the people. They weren’t sure which villagers to trust, and who might attack them. In contrast, the Viet Cong were skilled at guerilla warfare, and could make steady inroads one attack at a time.

After all, “shock and awe” tactics were what ruling powers used. Ho Chi Minh and his rag tag army of rebels favored a painstakingly slow war. One that could chip away at the occupying force bit by bit.

Year after year, the world watched footage of this overseas conflict from their TV screens. In previous wars, the atrocities were unseen, or proof of an enemy nation’s villainy.

During the Vietnam War, crimes against humanity were seen and reported among both sides, including the US troops.

President after president declared that this was a necessary war, one for the good of the nation and the world.

If you were a staunch opponent of communism, you could easily understand their arguments. This was indeed a proxy war, with China and Russia offering support to the Viet Cong.

But as the conflict escalated and then dragged on, more people began to question or criticize the US for its intervention in Vietnam. People who opposed colonial subjugation, or meddling in foreign political affairs, witnessed plenty to feed their outrage. Leftists who were not already sympathetic to communist talking points became a lot more so during this time.

This seemingly endless and pointless war sapped the US of human lives, morale, trust, and global standing. And it was ultimately all for nothing.

After nearly 25 years of war against foreign occupation, Ho Chi Minh died in 1969.

Just three years later, American troops pulled out of Vietnam.

We had never actually declared war, and had never officially surrendered, but the occupiers had finally given up. And Vietnam was finally unified under communism. Ho Chi Minh remains revered there as a national hero, Vietnam’s own George Washington.

The nature of Ho’s governance is a matter of dispute, given the self-interested nature of national propaganda on both sides. There are stories that suggest that he was brutal and repressive, just like Diem had been. Defenders say that the brutal rule came from other leaders, not Ho himself. It’s fitting that his name can mean “Light Bringer,” as he is depicted as both ascending savior and fallen angel.

Even if he did turn villainous, the Americans who knew him in the 1940s portrayed him as a decent man fighting for a noble cause.

What could have turned Vietnam’s George Washington into the next potential Stalin?

It was the foolishness of the Western nations that did so.

It’s true that virtually all of the nations who erupted into communist revolution turned into brutally repressive regimes, silencing and killing their own people. It makes sense to prevent such an ideology from gaining power elsewhere.

And yet, communist sentiment around the world was sparked by the rampant abuses of colonial powers. There really were horrific abuses that the US and Europe inflicted on weaker nations for the sake of making products like bananas and rubber available to consumers like us. Awfulness abounds.

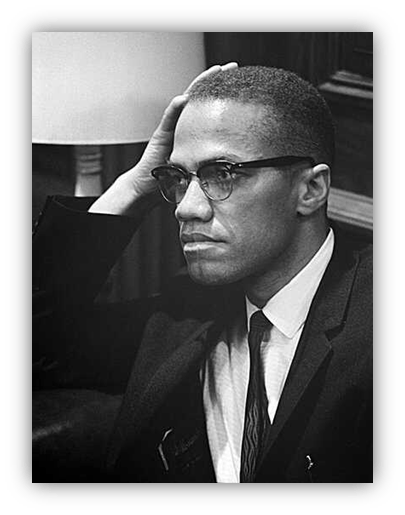

“Well, I said the same thing that everybody said. That his assassination was the result of the climate of hate. Only I said that “the chickens came home to roost,” which means the same thing. A climate of hate means that this is the result of something. And when I said chickens coming home to roost, I said the same thing.”

— Malcolm X on Kennedy’s assassination, 1964

We’ve previously covered how the flashy rhetoric of America and European democracies opened the door to real improvements with respect to rights and liberties. A lot of that rhetoric was just empty BS, but it provided us with ideals to work toward, and sometimes people actually brought us closer to those ideals. This was a truly wondrous thing.

Our victory in World War II had enabled this great shift toward collective forward progress. But it couldn’t last forever.

The quagmire of Vietnam perfectly encapsulates a time when the ideals died. The rhetoric curdled into fear, anger, and mistrust.

In some respects, I think we’re still stuck there.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

I fear it’s worse than that. Some of us are becoming who we once fought against. Yet, I think that tide is starting to turn. People are beginning to think, “This doesn’t feel right.” Let’s hope that trend continues.

“People are beginning to think, “This doesn’t feel right.””

I know what you mean. I pray for critical thinking coupled with objective reflection.

This is perhaps tangential to your point, but:

The over-exasperated antics of Jon Stewart make me laugh. But his final summation after the recent Presidential debate had me pondering rather than chuckling. The final 30 seconds:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3SJr44m-w1Y&t=875s

When I was in college, I took a class in wartime Germany. I guess it depends on who is teaching the class. Other people in other schools may not be exposed to the same set of information. Lucky for us, we had a Marxist, so we got the most depressing possible version of this period in history. And it’s easily verifiable. But, really, I wish I didn’t know this. It would have been preferable to learn about the past at the same time as most Americans who are a little leery about the direction of our country.

But here is a tactful recap of what I learned.

There is one American that the Fuhrer admired. He is mentioned in most versions of his memoir. The Fuhrer was inspired by a German translation of an obscure international text that the American republished at his newspaper. The one potential inflammatory detail I need to point out is that some scholars label this text as being “the original fake news”.

Arguably, it was this American who inspired by the German.

It’s been an open secret for years. It was supposed to remain an open secret. But one mainstream journalist started a podcast. She told the story of a movement in the 1930s that echoes today’s movement. But she left out the most important name. She saved that for her book, which was published earlier this year.

Unfortunately, her podcast and book, by all appearances, had zero effect on the political landscape.

Thank you for listening, V-dog.

Hate and aggression always win in the short term and lose in the long term. A few people make fortunes from this hate and aggression, stealing from the collective (both metaphorically and literally). We humans are collectively too stupid to realize this; it’s the mistake that animates our entire history.

The Third Reich was meant to last 1000 years, but lasted only 12. Israel burned every gram of October 7th goodwill by waging genocide against Palestinians in Gaza. The US has a lot of karmic debt to pay from Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan and numerous other aggressive follies.

I fear the moment we are living through is indeed the chickens coming home to roost, and we are just at the beginning. We either need to honestly come to terms with how inhuman we have been for centuries (starting with the genocide of Native Americans and enslavement of people stolen from Africa) and seek to truly do our level best to ameliorate these sins, or we will burn in the conflagration of our paradoxes. So far, to my great dismay and shame, all signs are pointing to the latter.

I don’t think that we bear the guilt of our parents’ sins, but we do often bear the consequences. US leaders had sown the wind at various points of history, and it’s the later generations that have to reap the whirlwind. We would do well to be introspective, informed, honest…and prepared.

I would argue we have to be all those things and more. We have to actively try to correct the past injustices or they will continue to haunt us. No I didn’t personally own slaves, but my ancestors may have, and I benefited from the system that allowed that travesty. It’s very comfortable to acknowledge the past transgression and passively reap the benefits. It’s something else entirely to try to truly correct those past sins and try to stop the active injustice still around us.

Yes, I think there are avenues to try to right those wrongs. Certainly in terms of correcting for systemic inequalities.

But I do also think that progressives take the rhetoric too far, from sober introspection (which is good) to a sort of performative purism, which sometimes sounds good, but usually isn’t practical. And often devolves into competitions of who is more pure and self-flagellating rather than actually righting wrongs.

Performative anything sucks… Just be yourself and be decent and honest. I agree the virtue signaling and gatekeeping has gone WAAAY too far.

And while some guilt is probably a good thing, don’t take it to the level of self-loathing. We all need self-love, and many of us deserve it too.

Brings to mind the quote; Those that fail to learn from history are doomed to repeat it’. The Internet disagrees on who said it first and the precise wording but it remains as relevant as ever.

There are plenty today seeking to cement their own power with short term thinking that prioritises their ego’s and lust for power without consideration for what that will mean when they’re gone. In doing so they want to deny any fallibility in our colonial actions and instead promote it as simply that’s the way the world was back then and we should celebrate those achievements.

Doesn’t matter that those days are long gone when you could rampage across the globe subjugating and destroying. Making (insert own country here, Donald doesn’t have a monopoly on this) great again distracts from the emptiness of what they offer now by giving a rose tinted view of the past and positioning it as something that’s under attack. The subtext is that you’ve got no future and now they’re trying to take our past away. It might work short term but if all you’re offering is the past it doesn’t provide a future.

On the topic of remembering the past, if you had asked me about the Vietnam War before 2010 or so, I would have said it was about the US trying to stop the communist Viet Cong from taking over the south. That’s all I knew about it.

My dad even fought in Vietnam, and I’m not sure if he knows about the role of France in the whole matter. It’s a murky, ugly story to tell, so we tend not to tell it. To our detriment.

Corollary to your quote: Those who prevent the teaching of history intend to repeat it.