It’s his first day in showbiz.

At orientation, he got a sneak peek at CBS’ latest sitcom. And now, the starry-eyed boy is being ushered across the hall by creator of HOGAN’S HEROES.

Sammy Fabelman (Gabriel LaBelle) makes the acquaintance of a weathered but not unfriendly secretary, the gatekeeper for “the greatest filmmaker who ever lived.”

As he settles down, cautioned about a potentially long wait, the camera pans circularly along the modest office, decorated with 1-sheet movie posters:

While “Ethan Returns” plays over the soundtrack.

The pan seemingly moves at the speed of a long-playing record. And then we hear the dissonant sound a needle makes when it’s lifted off from the groove with haste. The music stops. “Ethan” has returned from lunch.

THE FABLEMANS, directed by Steven Spielberg, depicts the three-time Academy Award-winner’s first day on the Universal lot, highlighted by a meeting with John Ford (David Lynch).

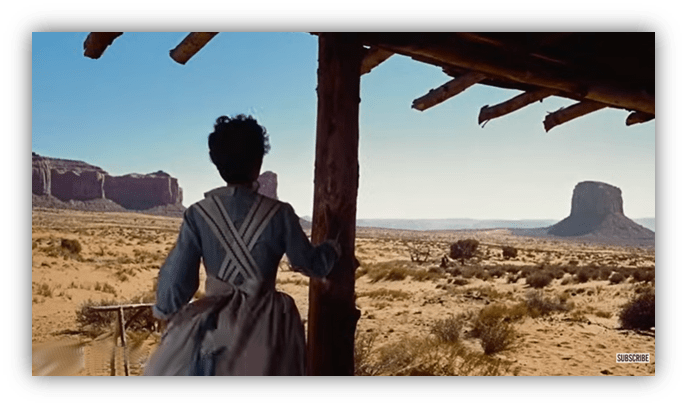

There is still time for Spielberg to broaden his horizons and make a western. But arguably, he already did:

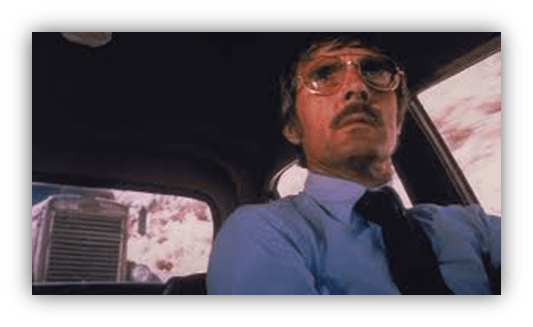

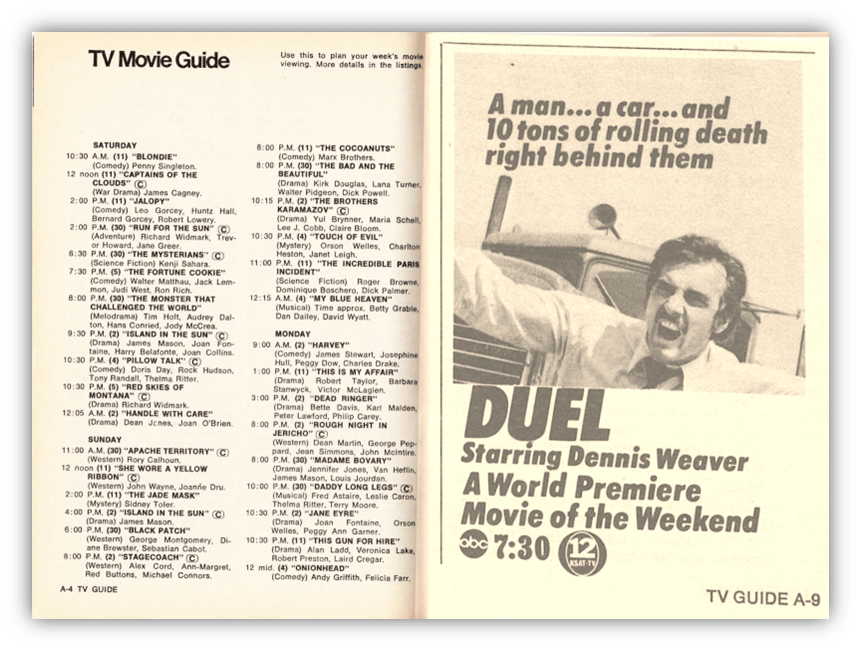

The made-for-television movie DUEL, starring Dennis Weaver as a man who could be John Wayne in search of a Gene Pitney song.

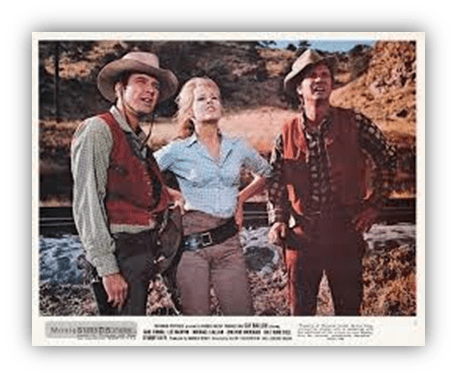

“Stand and deliver.” That’s Lee Marvin’s famous line from THE MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALANCE, the movie Sammy tries to watch in earnest, despite his friend’s horseplay at the bijou. Marvin plays the heavy who gives the 1962 film its namesake.

Spielberg got his start in an era when the western as a television staple was on a downward trajectory.

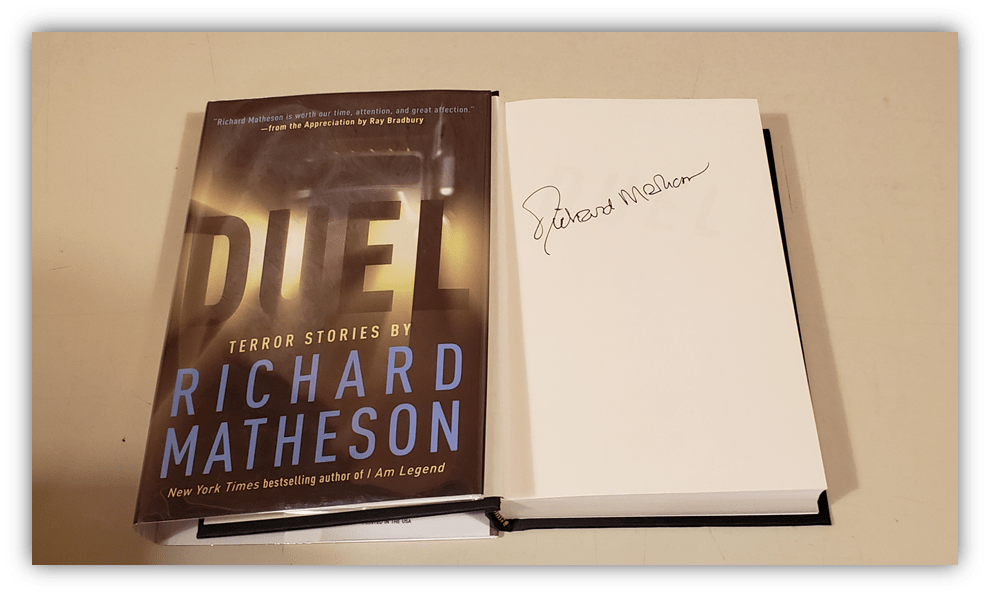

BONANZA still put up decent numbers. THE BIG VALLEY had its cultists, but the phone never rang for his services. The young filmmaker built his resume with stints on MARCUS WELBY M.D., COLUMBO, and NIGHT GALLERY. Spielberg’s moment of truth arrived when his secretary passed on a paperback copy of DUEL, a short story written by Richard Matheson.

Officially billed as an action-thriller, the adaptation beats the heart of a western, a homage to the Old West.

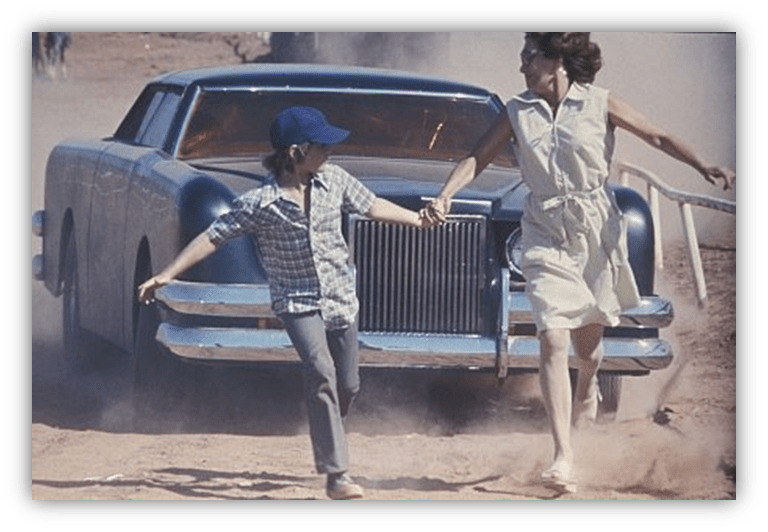

The car as horse, the diner as saloon, good car versus bad car going mano a mano, and a two-lane highway that runs through the Agua Dulce Canyon.

It’s all there encased in modern trappings, the lore. It’s tumbleweeds under car wheels; it’s frontier justice on asphalt. David Mann (Dennis Weaver) passes the wrong truck driver in the wrong truck, a vehicular maneuver in the light that sets the stage for a Hitchcockian take on DEATH RACE 2000.

The assignation of hero and villain is predicated on the size disparity between protagonist and antagonist.

It’s David versus Goliath. Ransom Stoddard in a duel with Liberty Valance.

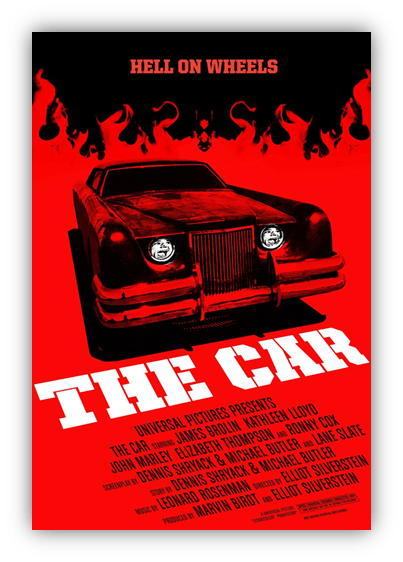

DUEL was no JAWS, the filmmaker’s game-changing third film which spawned countless imitators, but it did give us THE CAR, directed by Elliott Silverstein, a 1977 curio about a driverless car on the rampage in a one-horse desert town, starring James Brolin and the devil.

In spite of the Anton Lavey epigraph, THE CAR is less a horror movie than a western whose villain is, at the very least, a hit and run land shark.

Four years had passed since THE EXORCIST traumatized America, but with Linda Blair’s fully rotatable head still seared in the moviegoing public’s imagination, THE CAR got away with making hamfisted use of Satan as cover for an organic beast more conducive to the desert milieu.

The epigraph is a red herring. Silverstein, a journeyman of TV and film, would know his way around and how to play against genre conventions.

His filmography includes standard fare like HAVE GUN-WILL TRAVEL and BLACK SADDLE, button-down TV serials, both.

As well as CAT BALLOU, a western comedy.

The Lee Marvin vehicle was no spoof in the Zucker, Abrahams, Zucker vein, but Silverstein did poke softly at long-standing tropes, setting the stage for a more blatant distortion of the venerable genre. THE CAR is horror in drag, more THE SEARCHERS than THE EXORCIST with an allegory hiding in plain sight, which posits the car as steward of the land.

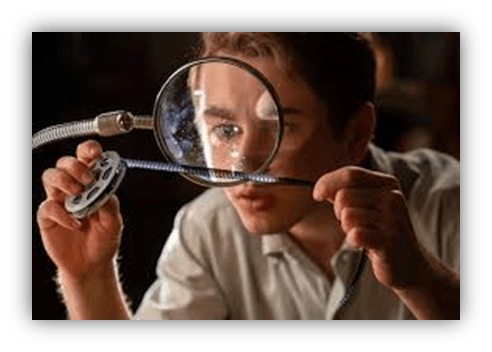

Angelo (Stephen Matthew Smith), the platoon sergeant in Sammy’s war movie, continues to walk long after the director yells “cut”, lost in Sammy’s filmic world of casualties, accountability, and shame.

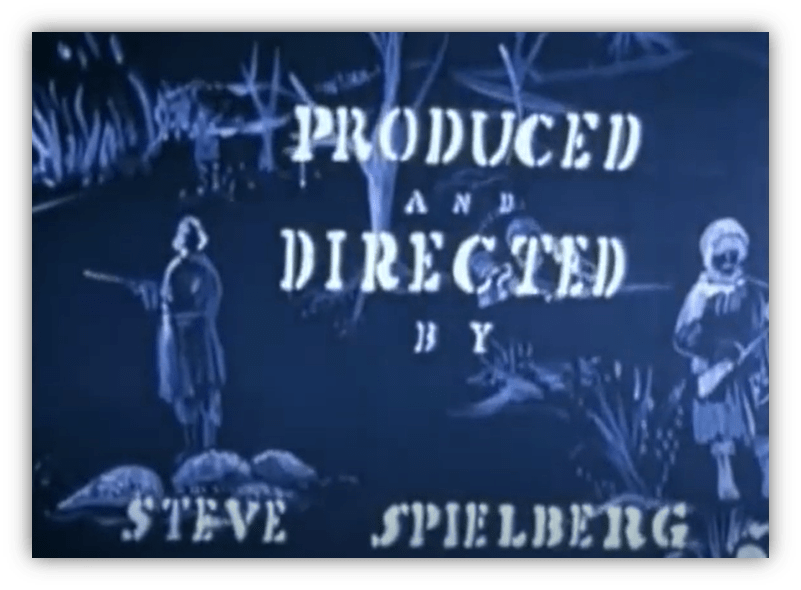

ESCAPE TO NOWHERE (1961) is a real WWII film Spielberg made with his friends.

Shot on 8mm, only two minutes exists from its original forty-minute running time, filmed under an Arizona sky intended to be East Africa.

At sixteen, the teenage David Lean mounted a production of the Abyssinian campaign. The coda functions as a backstory or prologue for THE SEARCHERS, in which Angelo, the John Wayne surrogate, keeps on walking until he ends up on the doorstep of his brother’s homestead. It doesn’t excuse his actions, though. Ethan Edwards fires two bullets into the open grave of a warrior, knowing that blind man can’t find his way to the spirit world. This Indian’s post-mortem blindness sentences him to “wander forever between the winds.” What if they made a film that showed where the damned go? What if the filmmaker didn’t tell anybody?

THE CAR opens with the horizon in the middle, a Lincoln Continnental Mark that materializes out from a flash of white light.

Against a mountainous backdrop, the car looks like an anachronism driving past sagebrush and cacti.

My prairie for a horse, the mis-en-scene calls out; my prairie for a bevy of heads amended by ten-gallon hats and headdresses; my prairie has ghosts.

The argument for THE SEARCHERS as having symptomatic meaning in THE CAR is the spontaneous gust that precedes each encounter between man and machine.

Furthermore, the sheriff’s office is integrated. As a horror movie, the filmic text reads as post-colonial; they’re simply lawmen, uniformed men and women working towards the shared goal of defeating Satan.

Observed through the prism of a western, however, the recalibration can’t help but foreground the Najavo as the “other”, because that’s how the historical film lens sees them. A municipal schism unveils itself through this alternative way of seeing. The police procedural as western honors tropes that reflexively assigns people into old formations.

It’s windy. Marching band gets cancelled on account of the car.

Lauren (Kathryn Lloyd), the sheriff’s fiancee, takes shelter in the cemetery, using it as a fortress to save her students from being the saddest roadkill.

Deputy Luke (Ronny Cox) describes the graveyard as hallowed ground. But Chas (Henry O’Brien), a Najavo, may have an altogether different interpretation of the term. In other words, whose god holds dominion over the skeletons that rest beneath the tombstones? Chas, the sheriff’s department’s translator, leaves out key details from an eyewitness’ testimony.

Dispatch tells Wade that the car had no driver. Some tribesmen believe in an anthropomorphic god. Is Chas one of them?

He drops Lauren off at home and inexplicably leaves, explaining that he has to check on a teepee. “Teepee” sounds dislocated, beamed in from a different movie, because there doesn’t seem to be a reservation in Shinbone. It could be bad writing, or slang for “house”, or more intriguingly, the western inside.

Chas, untethered from his textual role as friend, has a double, a foe who offers Lauren up for sacrifice. It’s performative synchronous time.

The actor, Henry O’Brien, has two choices. He can either play Chas as stupid, a lawman who leaves the woman with a killer on the loose, or he can play Chas as evil, an accomplice to premeditated manslaughter.

Nevertheless, Lauren’s pattern recognition is sorely lacking. The wild wind in the day is the same wild wind at night. The same wind Ethan describes as being purgatorial, the filmmaker reinvents, transforming the penitent wind into a wind of vengeance. Headlights like eyes appear in the window frame; it’s a raiding party in THE SEARCHERS.

Martha (Dorothy Jordan) tells her elder daughter to put out the lantern, but Scar (Henry Brandon) knows there are people in the sod house, just like how the car knows, or rather, Chief Cicatriz knows, there is no escape for Lauren, regardless of her poor decision to flick on the light switch. Scar is the car, an anthropomorphic god.

DUEL made its network television debut on November 13, 1971.

THE FRENCH CONNECTION just started its original theatrical run. In the car, there stood a good chance you’d hear “Gypsy, Tramps, and Thieves” on AM radio. While you waited in line for popcorn, you and your date could talk about Richard Nixon’s nationwide wage and price controls, or Mariner 9’s entry into Mars’ orbit, or Cher.

But twenty-million viewers stayed home that Saturday night to watch an avant-garde film.

DUEL travelled. A 93-minute version made the festival circuit. At twenty-five, the young filmmaker could not be easily intimidated, holding the press at bay, remaining defiant against the Spanish film critics’ insistence that DUEL explored class warfare, all but ignoring the horse’s mouth: “It’s a fight for survival between man and machine-made danger.” It really isn’t. The Spanish were right.

The young filmmaker, perhaps, wanted to keep John Ford close to his heart like a secret for a little while longer.

“Stand and deliver.” This time, it’s a friend who demands that the stagecoach passengers hand over their valuables.

Sammy’s sisters, Reggie (Julia Butters) and Natalie (Keeley Karsten), scream in unison, while Burt (Paul) gamely shakes the carriage.

In the background, there is a road, there is a moving car, there is enough visual information to envision the ghosts of a tractor trailer and car.

In DUEL, as David pulls into the gas station, he passes a disused stagecoach, a production design choice that audiences might’ve glossed over. The stagecoach works as a filmic bridge for Steven Spielberg to walk over and point out the ways DUEL honors John Ford.

David Mann owns a red Plymouth Valiant. Valiant/Valance, close enough. The driver stands-in for Ransom Stoddard (Jimmy Stewart).

That Valiant is no match for the tractor trailer, just like how Liberty Valance (Peterbilt 281) had a quicker draw than “Rance.”

In DUEL, David wonders aloud: “How does he go so fast?” Ransom had a partner, Tom Doniphon (John Wayne). The Valiant can be broken down into two components, car and driver. It’s two against one. Liberty never sees Tom’s gun pointing from his blind spot. David jumps out.

The car acts on its own. The car is more ornery than the driver. Both vehicles drive off the cliff.

The car dies.

But the driver was the bravest of them all.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Great write-up, cappie.

Admittedly, I have still never seen Duel, but I know the premise.

I was always a little confused about the title, given that it centered on a predator/prey chase rather than a mutually arranged contest. The idea that it’s at least toying with themes of classic Westerns makes some sense then. And the David vs. Goliath parallel makes even more sense given the outmatched threat of the truck.

A few years ago, another driver flew through a red light and smashed into my car. I was physically fine (God bless modern cars; and God damn DMV drivers), but I can still get anxiety triggers from accident scenes, the biggest so far coming from Punk Drunk Love and Better Call Saul.

All of this is to say that I hesitate to watch a whole film of a predatory Goliath truck menacing a hapless driver. I might have to take out the TV with a slingshot.

A few days after I turned in the essay, the state started posting this electronic message: Road rage is bad energy.

Some people get upset because there is a stretch of the freeway in which the speed limit is 35mph. The freeway. The road curves to the right. I’ve seen tailgaters over the years, because some motorists actually slow down to thirty-five.

I like my Honda Civic. I like modern cars. But what I like about period films, all the cars look distinctly different from each other. The Civic doesn’t look that different from a Toyota.

Thanks for reading.

Thanks for posting.

There are some people where I live zipping around in vehicles that look like something Batman would drive.

Whether Honda or Toyota, they sure look silly!

Good to have you back, cappie!

I saw the theatrical release of Duel, or I at least saw it in a theater. It’s such a tense movie, and the audience is left feeling the way David Mann does at the end: relieved that he beat his opponent but also wondering who the opponent was. He never even shows the truck driver’s face. There are many unanswered questions, which is exactly what Spielberg wanted

I’m pretty sure Duel is available on streaming services. It’s worth checking out if you’ve never seen it.

Thank you, V-dog.

You probably saw the ninety-two minute version. The original is seventy-three. Hard to believe it was made for television, right? I was addicted to Duel for a couple of days. No plot. Nearly silent. Very relaxing.

On the mothership, when they were asking musicians for their favorite Beatles song, one artist cited a Quarrymen song. I believe him now. Duel, definitely, would be more influential for an independent filmmaker than the rest of Steven Spielberg’s films. That musician probably was drawn to the rawness of the Quarrymen song.

Funny how some artists most creative work is their earliest.

I didn’t often watch random, unknown movies as a kid, but somehow I found myself watching Duel on some Saturday afternoon. Didn’t know it was Spielberg. Was not disappointed.

Yes. Duel is an outlier. Steven Spielberg isn’t an auteur, but his imprint is completely unrecognizable here. But, I haven’t seen his first major motion picture The Sugarland Express. Pretty cool. It stars Goldie Hawn. I guess she was the first major star to seek Spielberg out.

Nice to see you back at writer’s row, cappie. Your last topic was a movie that touched close to my heart because I watched it with my daughter. This one also hit close to home because Duel was a movie that I watched with my father a few years back when it happened to come on TV one night. My dad wanted to watch it because of Dennis Weaver, whom he recognized from Gunsmoke. I remember being riveted by it from start to finish. For me, it played like a horror movie. Never seeing the driver’s face made it even scarier to me, kind of like only seeing the fin of the shark for a good long while in Jaws. What is interesting is that in Duel, it was intentional. With Jaws, it was out of necessity, as the mechanical shark was terrible.

The premise of Duel is much simpler than what Spielberg would go on to do, but what is on display here is a clear indicator of the greatness we would all soon come to know.

Anyhow, great choice and I’m excited to see what’s up next for cappie.

Yes. I read the Judy Blume book twice. Kelly Fremon Craig deserved an Oscar nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay. Her tweaks really ironed out any perceived biases against organized religion. And Addy Ryder Fortson looked and acted how Blume describes Margaret.

Thank you, rollerboogie.

I was in a funk. But I had something to say about the Florence Henderson/Barry Williams duet. I had problems logging in. It’s true that nobody pays attention to the lyrics. In this case, however, every word is painstakingly enunciated. Oh, it is so weird. Gloriously weird.

Yeah, that was one time where you hoped they slurred their words and were unintelligible, but nope, loud and clear.

I am sorry to hear you were in a funk. I hope you are doing better these days. Whatever you were/are going through, know that you have friends here at tnocs and you are not alone.

It’s a long time since I watched Duel; the mid 80s. Probably a couple of years after I’d seen E.T. I was still a kid but I knew it was made by the same guy. Wasn’t quite as magical or child friendly as E.T. but I remember it being a tense and captivating watch.

Reading this makes me want to seek it out again. Great stuff cappie.

Thank you, JJ.

E.T. still casts a spell.

David Mann vs machine indeed! (How clever!)

Great job, cappie. Sorry this reply came so late — it’s been one of those weeks!