You’ve probably played a recorder.

These are foot-long whistles with holes down their length.

Their pitch changes as you cover or uncover the holes with your fingertips.

Some people get good at covering the holes perfectly, but most of us beginners miss slightly and get a weird squawk rather than a clean, pure note.

They’re popular in elementary school music classes because they’re cheap and easy to play.

But the plastic ones we grew up with aren’t the ideal instrument for professionals, or anyone who wants to make minimally pretty music.

A well-made recorder is a serious classical instrument.

Lots of music has been written for it, especially in medieval times. You may hear a professional playing one with an orchestra, or at a Renaissance Faire.

The idea for this sort of instrument goes back thousands of years. As I mentioned in my article about Guido d’Arezzo, the oldest instrument set we have is a bone flute.

Found in 1995 in a Slovenian cave, it’s at least 35,000 years old and is the hollowed out femur of a juvenile cave bear with holes bored into the side.

It’s played exactly like a recorder. Blow in one end and cover up the holes with your fingers to get different notes. The basic design hasn’t changed.

That flute was bone. Most similar instruments of the dark ages and Renaissance were wood. That’s where the name woodwind comes from. It’s wind going through wood.

Brass instruments are, in fact, made of brass and other metals, too. But the main difference between brass and woodwinds is how the sound is produced.

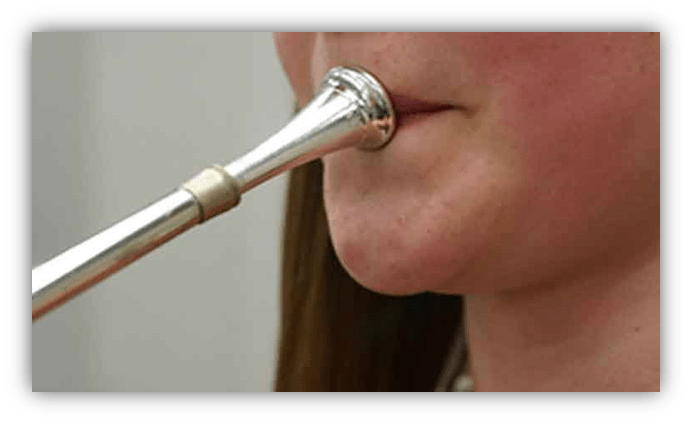

In brass instruments, the players vibrate their lips against a cup-shaped mouthpiece.

The Bronx cheer sound travels through the instrument’s tubing and the pitch is altered by changing the tension of the lips, as well as by using valves to redirect the air through longer tubes.

(Or in the case of the trombone, sliding the tube to make it longer).

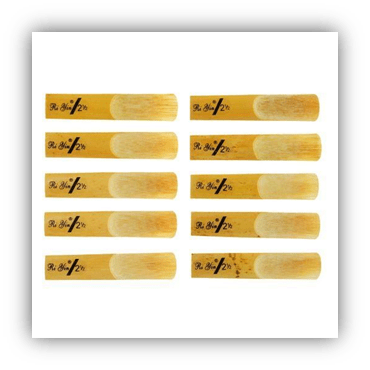

In woodwinds, the sound is produced either by blowing across a hole on a flute and piccolo (like blowing across a bottle’s opening), or by blowing through reeds. Single-reed instruments, like the clarinet or saxophone, use a reed that vibrates against its mouthpiece, while double-reed instruments, like the oboe and bassoon, use two reeds vibrating against each other.

While synthetic reeds are available now, most are made of the Arundo donax variety of cane found near the Mediterranean.

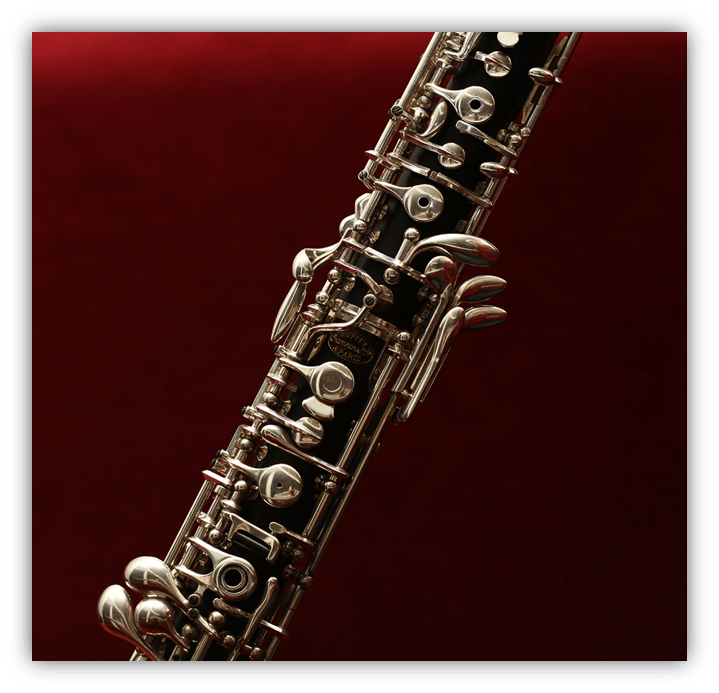

As woodwinds advanced past basic instruments like the recorder, a system of keys and pads to cover the holes was developed. The keys are the buttons you press with your fingers, and they’re connected by rods and hinges to circular pads that cover the holes. The pads have a cork or felt cover to completely seal the holes.

Not only does this system plug the holes more accurately than you’re likely to do with your fingertips, it puts the keys near each other, even if the hole is several inches away. That makes the instrument easier to play.

It’s pretty ingenious. But who came up with it?

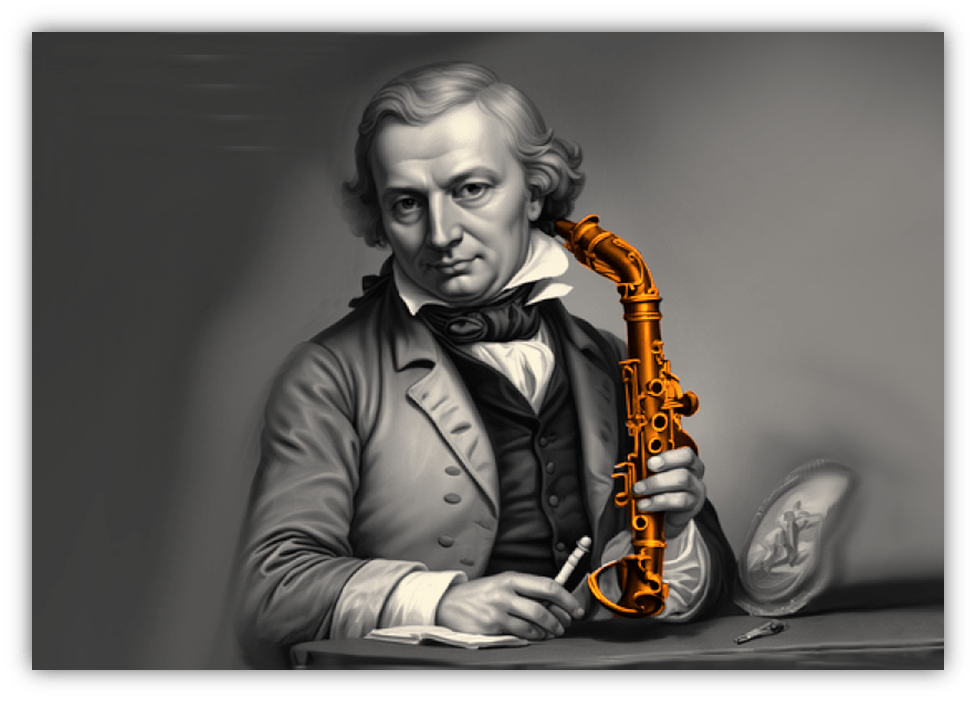

It’s a long history of craftsmen through the 17th and 18th centuries, each pushing the state of the art forward. We won’t get to them all here, but let’s start with Johann Christoph Denner.

Denner was born on August 13, 1655, in Leipzig, Germany, into a family of instrument makers. His father, Heinrich, specialized in horns and other brass instruments.

Growing up in this environment, Johann Christoph probably began training in the family workshop as a child and learned the fundamentals of wood and metalworking, tuning, and acoustics.

When Johann was still young, the Denner family moved to Nuremberg, a city that was becoming an important center for music. Nuremberg had a strong tradition of craftsmanship, particularly in clockmaking and musical instrument building. The city’s music scene, its atmosphere of innovation, and its growing demand for high-quality instruments, was fertile ground for Denner’s developing talent.

While his father focused on brass instruments, Johann worked on woodwinds.

He began by making and improving existing instruments, making numerous refinements to their tuning, playability and sound.

He was particularly skilled at balancing an instrument’s intonation, meaning its notes would be in tune with each other throughout its range. During his lifetime, he was known for his high-quality recorders, which were widely regarded as some of the best available.

One of Denner’s most significant contributions was his work on the chalumeau, a single-reed woodwind instrument that had been around since at least the 1200s. Its cylindrical bore and single reed produced a low, warm, mellow sound, but its limited range and somewhat crude design restricted its versatility.

Denner began making chalumeaux and worked to improve the instrument’s range and tonal flexibility. His most important innovation came around 1690 when he added a register key that opened and closed a small hole near the mouthpiece.

This essentially doubled the chalumeau’s range,allowing it to play both lower and higher notes, transforming it into a more versatile instrument.

Adding the register key to the chalumeau was so significant that it essentially led to the creation of a new instrument.

The Italian word “clarino” refers to a high trumpet, so the instrument was called a clarinet for its bright, trumpet-like sound in the upper register. Even today, woodwinds’ lower range is called “chalumeau,” and its upper range is called “clarino.”

While the chalumeau was usually played in ensembles, the clarinet’s wider range and dynamics made it perfect for both orchestral and solo performances. The new instrument quickly gained popularity in Germany and later spread throughout Europe.

Over the next several decades, instrument makers added more keys to expand the clarinet’s chromatic scale and improve its playability. However, none of that would have happened without Denner’s fundamental addition of the register key.

Denner died in 1707 but his legacy lived on through his instruments and his family. His sons, Jacob and Johann David, continued the family tradition of instrument making. Jacob, in particular, gained a reputation as an outstanding instrument maker in his own right, further refining woodwinds.

Louis Alexandre Frichot was born fifty-three years later in Versailles, France, the son of a cook in the court of the Duke of Burgundy.

Details about his early life are sparse, but we know he fled the French Revolution and by 1793 he was in England playing the serpent in an orchestra.

The serpent is a hybrid instrument with a cup mouthpiece like a brass instrument and a curved body made of wood and finger holes like a woodwind. It was hard to play, and not very loud.

In 1799, Frichot created the English bass horn (not to be confused with a bass English horn) as a replacement for the serpent. Unlike the serpent, it was metal and used keys and pads like the clarinet.

It was V-shaped. Composer Felix Mendelssohn said it looked like a watering can, but it produced a clear bass tone that was more powerful than the serpent. An 1825 article in the Quarterly Musical Magazine and Review described Frichot’s “very extraordinary performance” on an early bass horn.

A decade later, Frichot invented the basse-trompette as an improvement of the English bass horn.

Instead of the V-shaped body, its tube was bent upon itself, with a large loop and a smaller one. According to the patent, the lower curve of the smaller loop could be swapped with tubes of different length to produce different pitches.

It also had six finger-holes in two groups of three, as well as four or five keys. That strange configuration may have kept it from being popular, and I haven’t found any videos of it. I assume its closest current relative is the bass trumpet, heard here:

Frichot patented the basse-trompette in 1810. He meant for it to take the place of his English bass horn. It didn’t, but both instruments ended up being influential on other builders.

While most brass instruments of the time were made from brass or bronze alloys, Frichot experimented with different materials and construction techniques to improve the tone and projection of brass instruments. He also worked on improving valves, which were used more as they got better.

Like many instrument makers of his time, Frichot did not receive widespread recognition during his life.

His contributions were part of a movement of technical and acoustical improvements made by many individual craftsmen. He eventually returned to France and taught music in Lisieux.

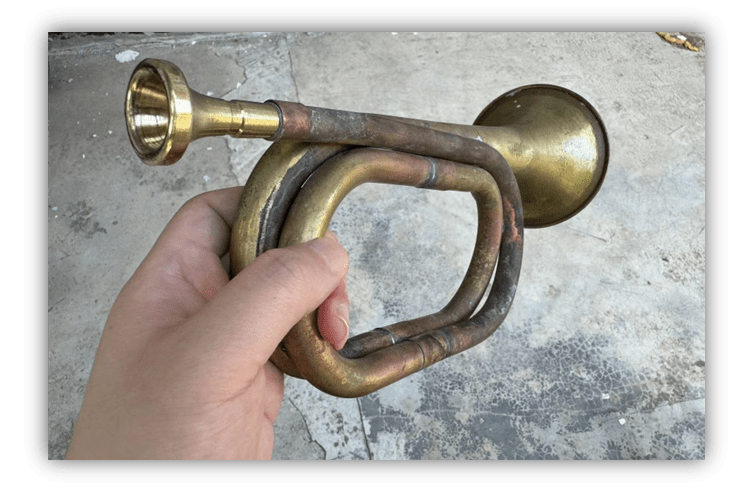

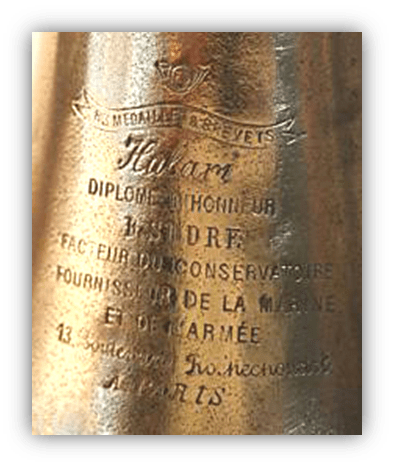

Jean Hilaire Asté was born in 1775 in Agen, France.

He was also known as Halary, but we have no information about his education or how he became interested in musical instrument making. His skill suggests that he had been an apprentice with an established instrument maker.

That was common for craftsmen of the time and would explain how Asté learned the art of metalworking, woodworking, and the acoustics necessary to make high quality instruments.

It’s hard for us to imagine how essential music was in military and ceremonial life in Asté’s day. With current electronic communication, music isn’t used in combat, but imagine war a couple centuries ago. Generals ordering their troops to advance or retreat wouldn’t be heard over the noise of battle. However, the troops would hear a band playing the music for each particular order.

Asté knew this and tried to make his woodwinds louder.

In 1817, he introduced his most famous invention, the ophicleide. Until then, bass notes in a marching band were played by the serpent and Frichot’s English bass horn.

The ophicleide improved on the bass horn. Asté’s innovation was to use keys from woodwind instruments for all the notes — meaning no finger holes — to improve intonation and accuracy. The ophicleide had a conical bore and used a brass-style mouthpiece, giving it a rich, robust sound. The keys gave the ophicleide a broader range of notes and was easy to play.

The ophicleide was an immediate success and was quickly adopted by military bands and orchestras across Europe. Its powerful tone blended well with other brass instruments while providing the bass foundation for ensembles.

Composers incorporated the ophicleide into their orchestral works, most famously in Hector Berlioz’s “Symphonie Fantastique” where it was used in the witches’ round dance sequence of the “Dies Irae” section. The instrument became a standard part of orchestras throughout the 19th century.

Following the success of the ophicleide, Asté worked on improving other brass instruments.

He refined the bugle, cornet, and other members of the brass family. He experimented with different materials, bore shapes, and key mechanisms to improve playability and tone.

His workshop produced a variety of instruments, and Asté became a respected figure in the French musical instrument-making community.

The ophicleide’s prominence began to wane in the second half of the 19th century as valved brass instruments…

…Particularly the tuba which was perfected by Wilhelm Wieprecht and Johann Gottfried Moritz- became more widely adopted.

Valves allowed for smoother transitions between notes and offered a more consistent tone across the instrument’s range, making valved instruments more versatile and easier to play than their keyed counterparts.

Despite the ophicleide’s decline, Asté’s invention had a lasting impact on the development of brass instruments.

The principles he applied — particularly the use of keys to improve intonation and playability — were important in the evolution of brass instrument design.

Asté’s work laid the groundwork for future innovations, and his contributions to music were recognized by his contemporaries, even if his most famous invention was eventually replaced by newer technologies.

- Denner added the register key to the chalumeau to make the clarinet

- Frichot created influential new instruments

- And Asté added keys to the English bass horn to make the ophicleide.

These may seem like small changes now but they were revolutionary at the time.

The clarinet quickly became a standard part of the orchestral woodwind section, alongside the flute, oboe, and bassoon.

Composers like Johann Stamitz and Carl Maria von Weber wrote significant works for the clarinet.

By the time of Mozart and Beethoven, it had become one of the most important instruments in Classical music.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, additional keys and mechanical improvements made it even more versatile.

It became central to new musical genres such as Jazz, and clarinetists like Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw brought the instrument to center stage.

Although the English bass horn, basse-trompette, and ophicleide are rarely seen in modern orchestras now, they still influence the design of contemporary brass instruments.

These innovations helped shape 19th-century music.

We’ll see their impact in our next article about one of our most popular instruments of the 20th and 21st centuries.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

.

Being half-Slovenian, I was quite pleased to see that a Slovenian cave made it into today’s article. It’s a small country that doesn’t tend to get a lot of mention.

You haven’t lived until you’ve been in a room with 30 4th graders with plastic recorders, trying to get them not to sound like a bunch of ducks that got stepped on. And failing.

Favorite rock song with a recorder? Ruby Tuesday. Take that, Stairway to Heaven and Fool on the Hill.

As a clarinet player, also glad to see that instrument highlighted. Somewhere, Mr. Acker Bilk is smiling.

I saw the Nashville Symphony play Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite last night and paid special attention to the woodwinds. The players were fantastic and good ol’ Igor knew what he was doing.

In Rite of Spring, reeding is fundamental.

Before the concert, the lovely Ms. Virgindog asked if Firebird was the one that caused a riot. I told her no, that was Rite of Spring. She said, “Good. I left my helmet at home.”

I was a clarinet player, too. I haven’t played much since college, but even as recently as 2021 I accompanied a singer during our church’s Christmas program.

Video, please.

I am convinced that just when I think I have seen every band instrument, there are probably double that amount out there somewhere.

I still have my recorder from 3rd grade, and I am proud to say that I can still play “Hot Cross Buns” and “Mary Had a Little Lamb” with aplomb!

The ophicleide, I’m still working on…

Thanks for another great lesson, Bill!

My career in music peaked at the age of 6 when I learned to play London’s Burning on a recorder. We had more robust recorders at school here than those coloured plastic ones. I don’t think it made for a richer tone or more pleasant listening experience.

I’m much happier reading about them than listening to them.

That serpent, two words: Cantina Band.

I’m looking at the Wikipedia page for bass trumpet. The first well-known bass trumpet player was Johnny Mandel. Wait, what? I checked to see if there was another Johnny Mandel. No, there is just the one. I mention this because I was listening to Yankees/Guardians on the car radio and the play-by-play guy mentioned how his name is similar to Johnny Manziel. This out of the blue observation was made when Cade Smith entered the game. He asked his partner: “Don’t you want to say Kate Smith?” Probably not, because his partner, a woman, sounded at least several decades younger.

The ophicleide looks like a descendant of the sousaphone or tuba.

And a quick shout-out to Slovenian filmmaker Damjan Kozole.

Other way around, but we’ll get there. There was, in fact, a tuba at the time but it was big, bulky, and hard to carry so wasn’t great for military bands.