“Get off me, Delilah.”

The piano recital is over. A bum note in the music room hangs in the balance. Burt Fabelman (Paul Dano) is puzzled.

Why did his wife, Mitzi (Michelle Williams), use a feminine moniker to address him?

{Hawaii-based film critic cappie the dog’s jaw dropped.}

{He dropped his pen.}

The author believes that screenwriter Melissa Mathison reveals E.T.’s true gender in the 1982 film’s waning moments.

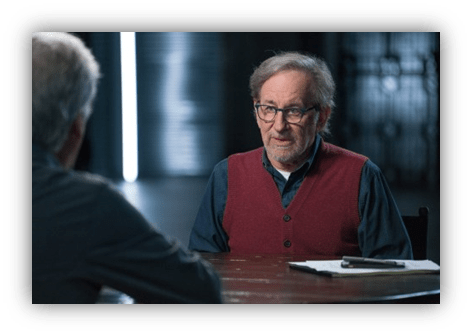

Delilah/feminine is left holding the nail clippers, while Samson/masculine (Seth Rogen) props up Mitzi on the piano bench, her reclining head just inches away from his lap. The father ends up on the feminine side of the gender binary, looking like E.T.’s stand-in when Sammy (Gabriel LaBelle) hugs him. The bedroom tableau replicates the final goodbye in the landing field. In a 2023 interview, Steven Spielberg said that E.T. became “the father I didn’t have anymore.”

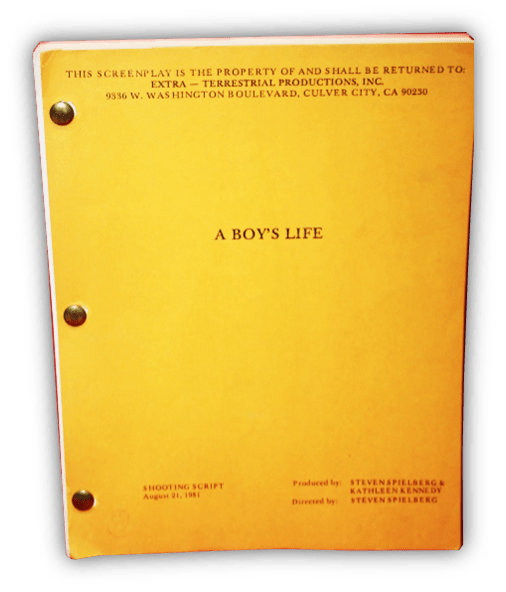

This little psychodrama can be interpreted as the catalyst for the Mathison script, originally titled THIS BOY’S LIFE.

Mitzi emasculates her husband, suggesting his lack of a penis, a performative castration that uses words as a scalpel. Elliott’s insistence of E.T.’s maleness, in retrospect, comes across as an unconditional defense of his father’s virility, severely tested by the mother’s cuckolding. Purposely incurious, unlike Gertie (Drew Barrymore), who asks if the alien was wearing any clothes, Elliott’s piqued reaction seems less visceral than extrinsic. The gender fluidity that Gertie instigates is an oscillating between diminishment and rehabilitation which vexes Elliott (Henry Thomas), his father’s staunch defender.

It brings to the surface a love and anger the son may feel towards dad for not being man enough to keep the family intact. The extra-terrestrial as the filmmaker’s childhood imaginary friend as being the inspiration behind E.T.: THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL was a known quantity.

But a father surrogate? That was new.

Celebrities are like us, after all.

Steven Spielberg, as did many Americans, believed that the COVID pandemic was an “extinction-level” event.

This boy’s life he saw flashing before his eyes, he got it down on paper, not knowing with absolute certainty that the trip down memory lane would go into production.

250,000 Americans died when the movie in his head unspooled like a celluloid strip: running through the final projector, rendering his memories with a soft and grainy quality. THE FABELMANS commenced shooting in March 2021, three months after the first vaccines were made available to the public.

Never a particularly introspective filmmaker, THE FABELMANS was born out of circumstance. We’ve seen this story before, the unofficial version, a story we intuited as being autobiographical, but unsure where the filmmaker’s life ended and the dream body began. “Dreams are scary.” Life was scary. Fear came to dominate Steven Spielberg’s life, as the novel coronavirus emerged to become the star of THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH.

His anxiety, quite fittingly, is advertised on the theater marquee, all lit up.

The incandescent heat felt both by an old man and his muse, the latter expressing reservations about the Cecil B. DeMille film he lined-up outside for with his parents, Burt (Paul Dano) and Mitzi (Michelle Williams) Fabelman:

The scientist and the artist.

To the clear-eyed, those gigantic people that alarm Sammy are “not real”, merely byproducts of rapid-fire light rays, a “persistence of vision”. To the hopeless romantic, they’re dreams. COVID felt less like life than a bad dream. To own this fear, the filmmaker picked up his camera, just like how Mitzi taught him, on SUPER 8, way back when. At seventy-five, predicting the inevitability of his body lying prostrate on the bathroom floor, Steven Spielberg phoned home.

“I’m glad he met you first,” the FBI agent tells Elliott, a hospital patient in his own house, as medics work on the boy’s wrinkly brown friend in the next bed.

Identifiable by a ring of keys, we can never positively I.D. the nameless bureaucrat (Peter Coyote), the “dogcatcher” of Gertie’s imagination, until late in the film.

Posited as the film’s antagonist, “Keys” shakes off that initial distinction of being E.T.’s arch-nemesis,

… Even though he and his colleagues were probably armed at the spaceship landing, not just during the extra-terrestrial’s pursuit on two wheels through the winding roads of suburbia.

On the nature/nurture question, Keys comes around to Elliott’s side, seeing firsthand how E.T. is akin to a bipedal dog, more exotic pet than national security risk. Still, a faint menace, an undercurrent runs beneath the kind words that praise Elliott for a job well-done. Younger audiences take the premise of the friendly alien storyline for granted. Pepperidge Farms remembers.

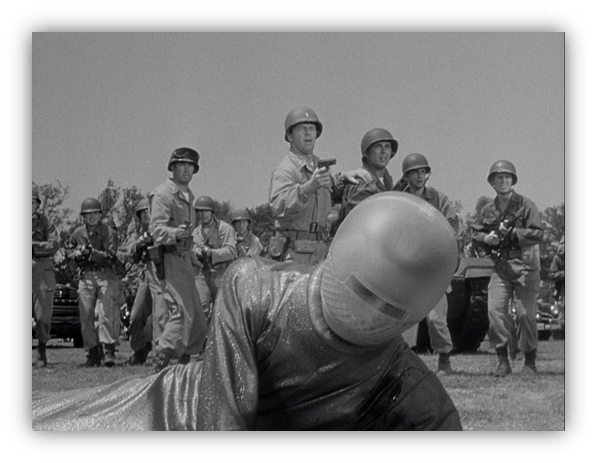

The filmic history of close encounters, starting with Robert Wise’s THE DAY THE EARTH STOOD STILL presumes the alien as a hostile.

Klaatu (Michael Rennie) comes in peace, but one false move by the humanoid is all it takes for a soldier to pull his trigger.

If E.T. was edible, as suggested in Bong Joon-ho’s OKJA, Lucy Mirando(Tilda Swinton), the CEO of a multi-national food corporation, without hesitation, would put the extra-terrestrial into production, despite being sentient and hyper-intelligent, like Okja. The super-pig, however, is earthbound. Pigs can’t fly. E.T. can fly. And perhaps, an underrated superpower.

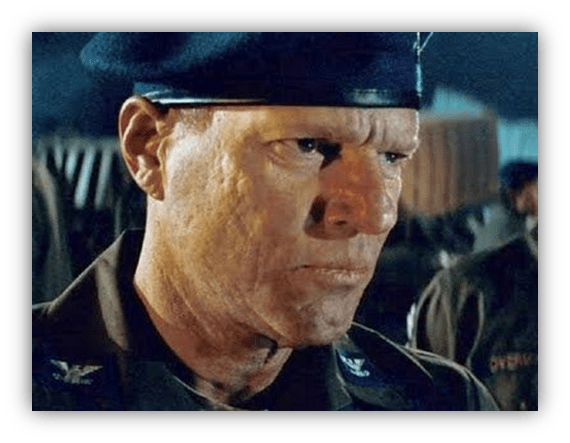

What if somebody like Colonel Nelec (Noah Emmerich) met the alien first? That glowing fingertip heals ouches. Can it hand out ouches, too?

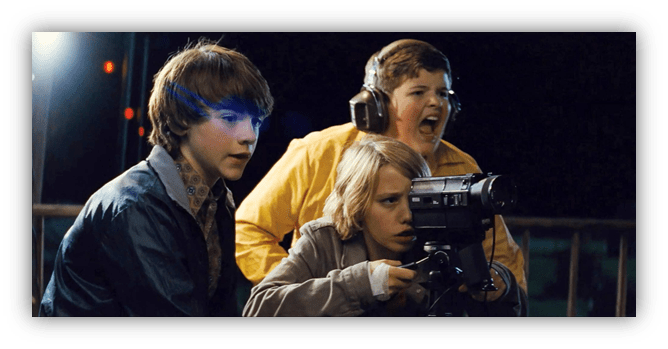

Joe Lamb (Joel Courtney), sound, makeup, and special effects, inspects the wreckage with his friends: Martin (Gabriel Basso), Ryan (Cary McCarthy), Preston (Zach Mills), and the pretty girl, Alice Dainard (Elle Fanning).

Loud and hyper, the ambitious AV club can’t stop talking about their near-death experience, a train derailment, right in the middle of shooting the latest scene for their zombie movie.

The fire, the explosions, the flying carbon steel, the running and screaming, went over everybody’s heads. Just another CGI-laden action sequence, we thought. The advent of THE FABELMANS, Steven Spielberg’s thinly-veiled bildungsroman, however, reveals this hitherto unsurvivable catastrophe was no spectacle in a vacuum.

Post-modern in form, JJ Abrams’ SUPER 8, a pastiche of Steven Spielberg’s imperial phase, including CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND, THE GOONIES, and E.T., as it turns out, was always six degrees of the biographical.

It presages THE FABELMANS, especially the train crash set-piece, in which the distant technicolor disaster, aforementioned as a COVID-19 metaphor, updated to Michael Bay-like scale, uncannily duplicates a two-fold horror the filmmaker must’ve vicariously felt directing his child-self watching not just the locomotive, but life itself go off the rails. Joe Lamb, the audience deduces, is Spielberg’s proxy, not Charles Kaznyck (Riley Griffiths), the director. Charles’ best friend and neighbor knows where to look.

Only Joe witnesses Dr. Woodward (Glynn Turman), the high school biology teacher, driving his vehicle on the track. Charles is pointing his camera in the wrong direction.

A head-on collision frees the live cargo, randomly named Cooper, a homesick alien who spends his entire post-crash life in secret government labs, suffering fools like Nelec, a sadistic Air Force careerist who lacks the intellectual curiosity to determine the accidental visitor as being friend or foe.

This should be the pivotal moment: boy and alien meet, since Joe recognizes excess movement in the boxcar. But SUPER 8 digresses.

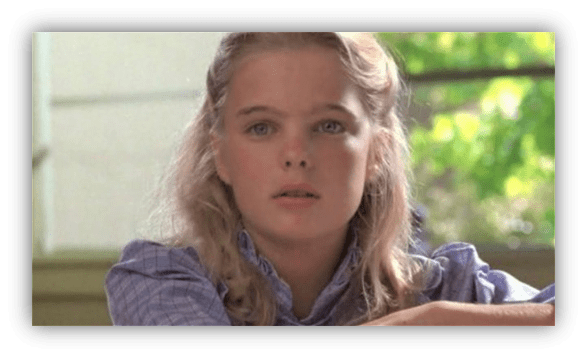

Being five years Elliott’s senior, the young teen, long outgrew the need for an imaginary friend, especially one from outer space, and starts looking for the pretty girl with a name. Quite pointedly, in E.T.: THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL, Erika Elniak, the young blonde at the bus stop and science lab, is nameless; she’s an adjective and a noun:

“Pretty Girl”, which can be turned into an acronym, just like the extra-terrestrial, whose name is, in essence, an adjective and a noun, too. She’s literally P.G.: THE PRETTY GIRL.

Ciphers, both; the mother, perhaps? E.T.(father figure/husband), after all, uses Elliott as a conduit to kiss the girl/wife. Oedipus for beginners?

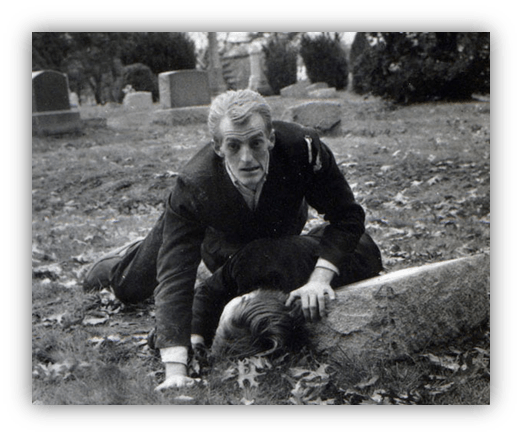

At the cemetery, leaning against his mother’s tombstone, the boy rouses when he hears noises coming from the gravedigger’s house.

For the second time, Joe Lamb avoids a close encounter; he gets on his bike and rides off into the gloaming. SUPER 8 has a filmic case of narratio interruptus; we wait patiently for the boy to befriend Dr. Woodward’s charge, a grieving Cooper, so E.T.: THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL can start to happen.

The twizzler Joe gives to Alice Dainard by right should be the alien’s candy. Junk food is how the extra-terrestrial reaches Elliott’s backyard.

No Reece’s Pieces, no name, that’s Spielberg logic. But Elliott is ten. As a result, E.T. gets a life, whereas Cooper takes a backseat to puberty and cinema, in that order.

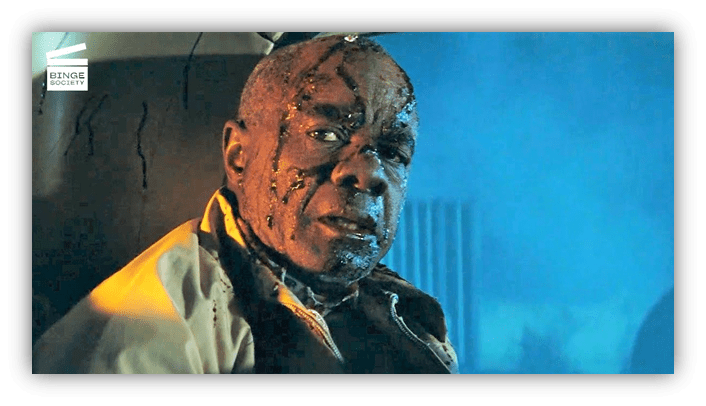

Dressed like astronauts, Keys is one of the FBI men who invade the house and converge on its occupants, looking less like characters from the Old Testament than the undead. Packed in ice, written off as dead, the extra-terrestrial’s self-rejuvenation is often interpreted in biblical terms, but maybe the alien’s post-life has been mistaken for another broken law of physics all along.

Charles’ zombie movie suggests that Spielberg was referencing George Romero’s NIGHT OF THE LIVING DEAD. In addition to being the castrated father, E.T., a zombie, too? At the dinner table, in THE FABELMANS, with Mitzi at her hungriest, she says: “I love Burt’s brain.”

The mother leaves half of the masculine/feminine binary hanging in the air like an unplayed note. The female gaze is implied. The camera is omniscient. Mitzi faces Delilah/Burt Fabelman, not Samson/Benny, the husband’s best friend. A second camera, Sammy’s 8mm camera, in-frame, is naively subjective, when he inadvertently captures the female gaze, his mother facing toward, not away from Uncle Benny on a camping trip. The boy’s vision, newly abled by a transplanting camera eye, we watch Sammy take stock of the father, and being disappointed about the impotence he projects in allowing the “uncle” to drive his wife home without protest. In E.T.: THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL, Elliott’s father is out of the picture. For narrative’s sake, he and his mistress are rendezvousing in Mexico.

In real life, E.T. was an imaginary friend Spielberg invented to deal with his parents’ imploding marriage, a coping mechanism.

The moment Sammy Fabelman disallows his mother and uncle to bathe in the afterglow of another well-received movie exhibition, E.T. is born, without genitalia. In time, the genitalia forms. Its specificity predicated on how Benny steals the matriarch away from her family, leaving Burt, a hapless eunuch.

Jackson Lamb (Kyle Chandler) seems like the kind of guy who can land a punch. Louis Dainard (Ron Eldard) was just a friend from work. Had he messed around with the sheriff deputy’s wife, the townsfolk would’ve been talking about that wake for years.

From the swing set, Joe watches his dad forcefully hustle this uninvited guest into the police car. It’s exactly how Sammy Fabelman would have wanted his father to handle a philanderer

The lawman is more Samson than Delilah. SUPER 8 works as an inverse of THE FABELMANS, in which the father/son dynamic creates a sideways iteration of E.T.: THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL.

Finally, Joe meets Cooper, a twelve-foot humanoid, under the water tower. Referred to as “it” by Colonel Nelec and Alice Dainard, the extra-terrestrial could be both.

“But not everyone is horrible.” The monster disagrees. He picks Joe up. The boy feels its feelings.

Fay Wray tells King Kong: “I know bad things happen.”

The monster open its inner eyelid, incensed at Joe Lamb’s ignorance. But puts him down.

E.T. didn’t flee. Elliott’s friend chooses to return home

Cooper flees.

It’s the year the earth stood still again.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

I have seen all 3 of these movies (E.T. multiple times). E.T. is an all-timer for me. I loved Super 8 and consider it highly underrated. I enjoyed The Fabelmans as well, though not as much as the other two. The connections you are making here run very deep and I was lost on some of it, but I enjoyed being enlightened to a thread running through all three.

Very similar. I’ve seen E.T. many times. When introducing my daughter to the best of the 80s she resisted E.T. for a while but she got into it eventually. Super 8 and The Fabelmans I’ve seen once. Super 8 was great but I need to give The Fabelmans another go. Watched it on a transatlantic flight with a lot of turbulence so it wasn’t the best conditions to concentrate on.

Enjoyed the read, lots of interesting points and connections that make me want to revisit all the films and join the dots for myself.

My daughter loves E.T. and she doesn’t always like 80s movies.

It’s interesting to see what holds up and what doesn’t. The Goonies was a total bust.

Whereas in our house The Goonies is an all time favourite for our daughter. The 80s movie she’s watched more than any other.

It’s in the National Film Registry.

Did you know Maureen McCormack auditioned for the part of the mother? Dee Wallace is fine. She’s in Wes Craven’s The Hills Have Eyes. I like to imagine Wallace was playing the same character, mom before she settled down. Wallace got typecasted. Just horror films. Gertie is smartest of the three children. Maybe that’s why your daughter likes it.

I may have heard that somewhere. Dee Wallace was perfect.

My daughter loves so many things about that movie, but Gertie is a big draw for sure.

I like fun Spielberg better than serious Spielberg. The Fabelmans is kind of both.

Count me in on the Super 8 fandom. Great movie.

I have the whole film memorized. When it was made, I didn’t realize what a major studio movie would look like today. In retrospect, this should have been a Best Picture nominee. That kid, Charles, played by Riley Griffiths, that’s pretty much his own film credit. He did “lean out”. He played football at Montana State.