Let’s put aside questions about the morality of colonization for the moment.

Throwing indigenous people off their own land isn’t something to be proud of.

But remember: it was royalty who put it into action…

… and royals tend to have unrealistic opinions about their country’s place in the world.

Many of the actual colonists were simply living the lives they had been brought up to believe were good and honest and patriotic.

In the 1600s, colonists settled in North America and they did so in slightly different ways. The British sent entire families.

The French, on the other hand, were soldiers, missionaries, and fur traders.

There were two French men for every woman, which makes it difficult to populate a continent. In the competition for the New World, the British increased their numbers through procreation. The French couldn’t.

In 1660, three decades after winning Canada back from the British, there were only 2,500 French colonists in the St. Lawrence Valley.

The 262 single women among them had paid their own way to get there, or had been sent by religious groups or their families. Some had signed marriage contracts or entered into indentured servitude. They hadn’t traveled for the fun of it. It was a harsh life in the New World and chances were that they’d never return to France or see their families again.

Their lives in France must have been pretty bad for this to look like a better option. That is, if the choice was theirs.

Jean Talon, Count d’Orsainville, was the first Intendant of New France.

As such, his job was to oversee the colonization of what’s now eastern Canada, the Great Lakes region, and the Mississippi River valley.

He recognized that the shortage of women was a problem to King Louis XIV’s expansionist goals, and he came up with a plan.

Talon proposed that the king pay the expenses to move women to Canada for the purpose of marriage and childbirth. The expenses would include the cost of passage, clothing, and a dowry. Any new family who produced ten living children, not including those who became priests or nuns, would be paid 300 livre a year. A family with at least twelve children would get 400 livre.

The king approved the plan and directed principal minister of state Jean-Baptiste Colbert to begin recruiting women.

These women had to be healthy, strong, smart, and beautiful or at least plain.

Applicants would have to provide a reference from a priest or judge certifying they were of good moral character. Farming and housekeeping experience were important, too.

These women came to be known as les filles du roi:

The King’s Daughters.

One of the places Colbert turned was La Salpêtrière in Paris. Built as a gunpowder warehouse, it had been converted to a women’s hospital for the poor, orphaned, mentally ill, and disabled. It was a bleak place, filthy, cold, and full beyond capacity. Police also brought prostitutes there to get them off the streets.

This may be why many people assumed les filles du roi were prostitutes. The rigorous approval process would have rejected them, but some Quebecois still believe their filles du roi ancestors were prostitutes expelled from France. There is only one known instance of prostitution among the 770 filles du roi in Canada, and that woman turned to sex work in desperation after her husband abandoned the family and returned to France.

Two women came from Canada to help in the selection process.

Jeanne Bourdon and Élisabeth Estienne interviewed inmates at La Salpêtrière and made offers to the women who met their standards.

About 250 of them took the opportunity for a new life, though it’s unclear how many actually understood how hard subsistence farming in Canadian winters can be.

While Talon’s idea was to send 500 women west, about 770 were accepted and set sail between 1663 and 1673. Most of these women were between 12 and 25 years old. Many were orphans or widows or just plain poor. The few from better circumstances were expected to marry officers. We know for sure that at least 730 were married within a few months after arriving in New France.

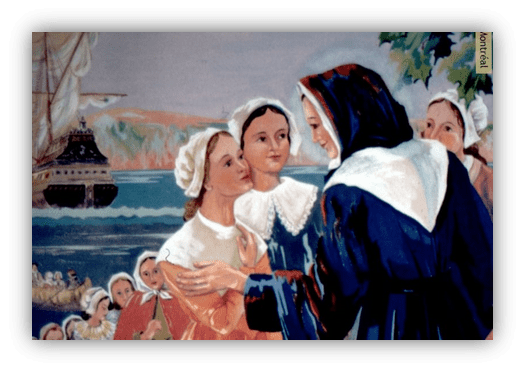

All of les filles du roi were brought to the three main cities on the St. Lawrence River. Quebec City was the first stop, then Trois-Rivières, and Montreal.

The story goes that the prettiest women got off at Quebec because they would marry quickest.

Most articles and videos about les filles du roi include a painting called The Arrival of the King’s Daughters in Quebec by Eleanor Fortescue Brickdale.

These women were poor and the dresses provided by the king would not have been so luxurious. Silk and satin don’t stand up to farmwork. Also, the voyage took six to twelve weeks. That’s a couple months of seasickness, poor hygiene, and cramped quarters. It’s estimated more than 10% of the women who boarded the ships died en route. Les filles du roi would not have arrived with such good clothing and complexions.

However, the disembarkments were always festive, and not just to celebrate a safe voyage across the ocean.

Government officials, religious leaders, and available bachelors were sure to greet the new arrivals.

Most were housed with families or nuns to be kept safe from unscrupulous men, but they were also encouraged to meet and marry as soon as possible. There was a process resembling today’s speed dating, and it was up to the woman to pick a man, not the other way around. For many of these women, it was the first choice of any significance they ever got to make.

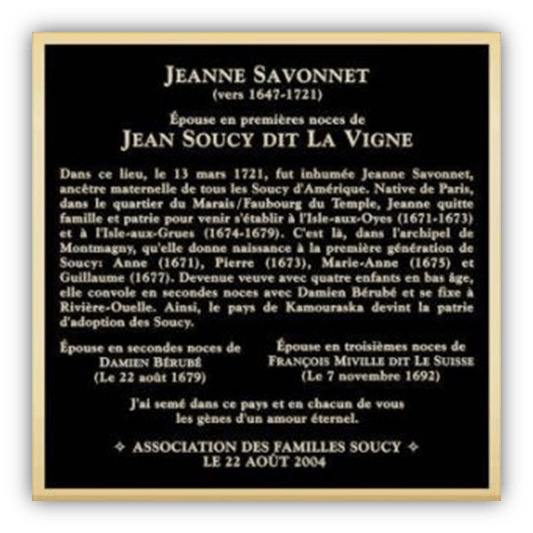

Let’s look at one fille du roi named Jeanne Savonnet who’s now known among her many descendants.

We don’t know much about her life in France except that she was born to Jacques Savonnet and Antoinette Babillette in Paris. She arrived in Quebec on July 31, 1670 on the ship La Nouvelle-France. There’s no suggestion as to why she left France. She was probably 22.

Jeanne met Jean Soucy, who had arrived in Canada from Abbeville, France in 1665 as a soldier. Many soldiers were encouraged with offers of money and land to stay in New France after their service. More than half did, and Soucy was one of them.

He had signed a marriage contract in 1669 with a fille du roi named Madeleine Maréchal, but the contract was canceled a week later. We don’t know why.

He and Jeanne married the following year, shortly after her arrival. It’s thought that they wed on Île d’Orléans, a large island visible from Quebec City. Neither their marriage contract nor certificate survive, which is typical of record keeping on the island.

The couple moved to Île-aux-Oies, which translates to Goose Island. We don’t know what sort of homestead they set up, but the Augustine nuns there were known to go to Quebec City to sell cheese, meat, and geese.

Dairy is still the main industry.

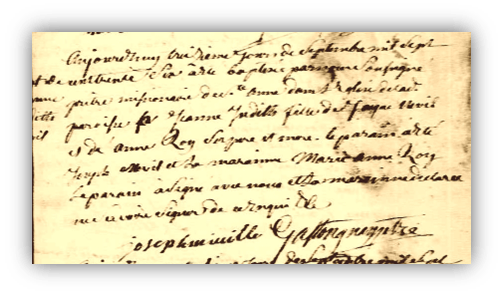

Jeanne had her first child, a daughter named Anne, on September 5, 1671, fourteen months after arriving in Canada. We’ll get back on Anne shortly.

Three more children arrived: two boys and a girl.

The youngest, Guillaume, was baptised on May 1, 1677. That’s the last record we have of Jean being alive. It’s believed that he drowned and his body wasn’t found, which would explain why there’s no burial record.

Two years later, Jeanne married Damien Bérubé in L’Islet, a town on the south shore of the St. Lawrence across from Île-aux-Oies.

Damien was 30, she was 29. Originally from Rocquefort, France, Damien was a mason, apparently a very good one, and had received ten acres of land along the Ouelle River as a concession.

Jeanne may have had some culture shock going from Paris to a barely inhabited island to a town where her new husband was well-known.

Damien and Jeanne had six children together, three boys and three girls. The youngest was born five months after Damien and two of the other children died, presumably from an epidemic.

This left Jeanne with eight children and no husband.

We’re not sure how she supported the family — Anne would have been 10, presumably she and the other children did chores, and maybe her neighbors helped — but Jeanne didn’t rush to marry. Four years later, in 1692, she married her third husband, François Miville.

He had come to New France from Brouage when he was a boy with his parents and five siblings. His father was a master carpenter and was granted land in Louzon, across the river from Quebec City.

When they married, Jeanne was 43 and François was 58. He was a widower with thirteen children, he was parenting his deceased brother’s four children, and he and Jeanne had one more child together. They’re just one example of how well the filles du roi program worked.

François and Jeanne stayed together until his death at the age of 77 in 1711. Jeanne died on March 12, 1721. She was about 73 years old. She’s buried in Rivière-Ouelle.

Now, back to her firstborn, Anne Soucy:

- At 19, she married Jean Lebel in Rivière-Ouelle. Jean was one of those rare people of the time whose parents were both born in New France.

- He and Anne had five children together but he died at the age of 30. We don’t know the cause of his death.

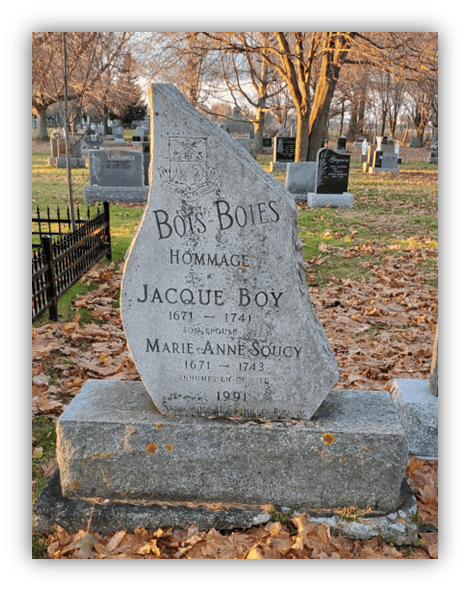

- Five years later, in 1704, Anne married Jacque Boÿ. They had five children together, including twin boys. Jacque bought land on the bank of the St. Lawrence and started a fishing company in 1710.

- Jacque had been born in Poitiers, France to René and Renée Boyer, but given the widespread illiteracy at the time, Boyer could easily be spelled Boÿ. He was a soldier, landing in Quebec in the regiment of Baron de Longueuil. We’re not sure why but his nickname was La Baguette.

He arrived in the early 1690s.

When the war with the Iroquois ended in 1701, he continued to work as a guard in Montreal and may have been a butcher as well. This makes sense because his father was a butcher.

Records say he had some trouble with the law and had to leave Montreal in a hurry. One account has it that he and an accomplice were jailed for robbing a surgeon’s house. They were sentenced to death, but escaped. The accomplice was captured and hanged, but Jacque went two hundred miles downstream and settled in Rivière-Ouelle.

He seems to have given up his thieving ways and became an important member of the community. Marrying into the Soucy family raised his status even higher.

His generosity and physical strength were admired, and he was often asked to witness weddings and funerals, which means he could sign his name, and possibly read and write.

Sometimes his name was spelled Jacque, sometimes it was Jacques, depending on who was doing the writing. And not only was it Boyer or Boÿ, it was sometimes Bois. When three of their grandsons applied for marriage across the river in La Malbaie, the clerk added an “e” to make it Boies.

Anyone named Bois or Boies is descended from Jacque and Anne.

They’re my 6-times great grandparents.

Likewise, anyone named Soucy are descendants of Jean Soucy and Jeanne Savonnet. They’re my 7 times great grandparents.

This isn’t unusual.

With 770 women having an average of 5.4 children each, most people with French Canadian heritage can count at least one fille du roi as an ancestor.

In 1991, Les Association Families des Bois put up a memorial on the 250th anniversary of Jacque’s death.

I went to the cemetery in Rivière-Ouelle a couple weeks ago and took this photo.

In the same graveyard, the Bérubé family has a similar marker, as do others. In my photos, I see one labeled Savonnet but I failed to notice it at the time.

While the Maison Saint-Gabriel museum in Montreal preserves the place where fille du roi stayed until selecting husbands, there is no national monument to them.

Given the sheer number of their descendants, and the perseverance, backbone, and grit of these women, there should be.

There is, however, a Montreal roller derby team called Les Filles du Roi.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

“With 770 women having an average of 5.4 children each, most people with French Canadian heritage can count at least one fille du roi as an ancestor.”

so does that mean you can come to Celine’s family reunion

I’m bringing a tourtière for the pot luck.

I could tell where this was heading, but I enjoyed the journey just the same. Great job of storytelling and educating, Bill. I learned a lot from this. Have a good weekend.

Cool story!

Last time we visited Montreal, we stayed in a house that was very close to Maison Saint-Gabriel, and checked it out on a lark during a walk. So we learned all about the filles du roi and the insane conditions they endured. It’s a cool site to visit if you’re in the area.

There is also a small park nearby named after the woman who was their principal caretaker, Marguerite Bourgeoys, and it serves as a memorial to the king’s daughters as well.

Great that you can trace your lineage back to the beginnings of New France. My dad doesn’t even know his grandfather’s name, and my mom said her side of the family used a fake surname because they were criminals. Can’t really get too far beyond a few generations.

Good to know we’re both descended from felons.

We stopped in Montreal on our trip, but the city looks like it’s seen better days. There were potholes in even the main streets and trash everywhere. I’m not sure what’s going on but we stayed only long enough for lunch and to see the statue of Louis Cyr, the strongest man in the world. He may be a relative on my mother’s side of the family but I haven’t confirmed that yet.

Quebec City > Montreal!

Nordiques > Les Habitants!

(Though I did manage to crash a wedding in Montreal back in 1995, something I did not do in Quebec City)

Looks like that’s near Place St. Henri which is…developing, you could say. It is definitely better now than it was, though some areas remain rough.

The closer you get to the canal and Marche Atwater, that area is lovely. And not all too far from Maison St. Gabriel.

Potholes are an eternal problem of Montreal.

I didn’t think the potholes would be that bad this early in the winter but, yes, Place St. Henri is the closest Metro station to the Louis Cyr statue.

Striking family resemblance, don’t cha think?

Hmm. Not sure. Maybe if the light is just right.

If the rumours of my father’s father’s father are true, count me in on the “descended from felons” list. Hail Scotland!

When I stayed with friends of mine in Dunedoo, NSW, Australia, the patriarch had the arrest warrant of their ancestor framed on the living room wall:

He’d stolen a cucumber.

8th Amendment, anyone?

My grandfather came from Sicily in 1912. He spent a night in jail for pummeling a guy.

Plot twist: The victim was a member of the {cough} “local neighborhood businessman’s association,” who would not take ‘no’ for an answer regarding the group’s offer of “protection services” for my grandfather’s shoe repair shop.

Unlike the Soprano-esque outcome that you would expect, they just left him alone after that.

I don’t know if I’m descended from felons, but there are likely a few somewhere in the family vine. I’ve heard that my mom’s family name is a crime family back in Sicily, and I do know that one of her first cousins changed his surname in the United States so he could become a lawyer without questions about the lineage.

I knew nothing about any of this piece of history. Very interesting, and it’s so great you can trace your lineage back that far, Bill.

I knew about Jacques Bois but only learned about Jeanne Savonnet and les fille du roi recently, and still learning more. The French Canadians did a pretty good job with record keeping but I’m pretty astounded we know as much as we do.

That’s pretty amazing you can trace your ancestry so well, Bill. My French cousins came to the States back in 2019 and shared with us some details, but they are sketchy at best.

Good to see those “Beautiful, healthy, strong, smart” genes are still doing some heavy lifting!

I’ll admit, I spent the first few paragraphs thinking this is an intriguing back story to the invention of a musical instrument.

Just as fascinating a story it turns out. I learned a lot. Parochial attitudes mean the history I was taught focussed on our role in the world so I learnt nothing about the how the French colonial claims progressed. They were only dealt with in terms of being historical adversaries.

Canada is number one on my daughters lengthy travel bucket list so we might get there at some point. I’ve been twice taking in Toronto, Montreal and Niagara. Would love to go back and explore more.

I highly recommend Quebec City. As a European, you might not be impressed by its Europeanness, but it’s beautiful. We made an overnight side trip to Ottawa, too. I hadn’t been there before but I want to go back for longer. And when its warmer. Brrrr!!!!

It’s funny…when people ramble on about their family history which has nothing to do with me. I find it FASCINATING. I really love hearing the stories, warts and all. Thanks for sharing, Bill!

Now I know the source of the name of the Marche Jean Talon, the awesome market in Montreal.

Very cool story!

There’s a street named after him in Quebec, too.