The Hottest Hit On The Planet:

“Rhapsody In Blue” by Paul Whiteman (featuring George Gershwin)

In 1924, drunk with ambition, success and the ego that comes with having your name printed on half the hit records in the Victor Records catalogue, Paul Whiteman:

Who was indeed a white man – let’s get all of the jokes out of the way before we begin…

…decided that it was about time that pop music, or jazz music, or whatever you wanted to call what he did – Paul personally preferred “American Music” – received some respect. Some critical accolades. To be considered equal to hifalutin European operas and concertos.

Being the most famous band leader in America, regularly referred to in the newspapers as “The King Of Jazz”, Paul had multiple tools at his disposal. Interviews with journalists for example, in which Paul would tediously hold forth upon the qualities of “American Music.”

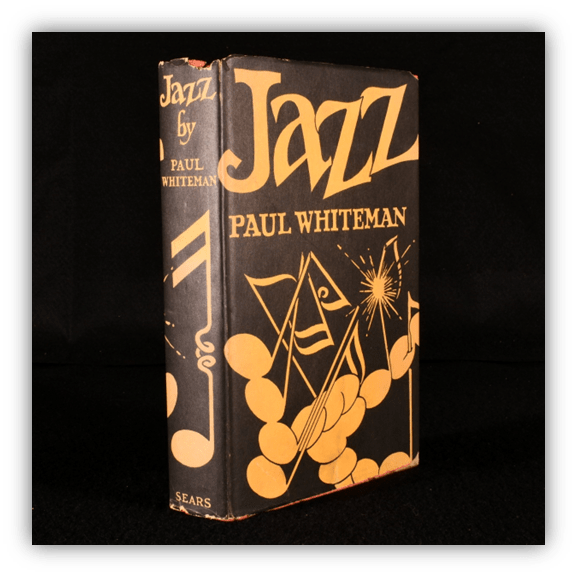

He held forth even more tediously when he wrote an entire book on the topic – titled Jazz, because of course it was – which featured such passages as:

“Jazz is the spirit of a new country. It catches up the underlying motif of a continent and period, molding it into a form which expresses the fundamental emotion of the people, the place and…”

(Goodness, he does go on, doesn’t he?)

“…it evolves new forms, new colors, new technical methods, just as America constantly throws aside old machines for newer and more efficient ones.”

He made pop music sound like a Ford assembly line.

That book would not be released until 1926, by which time Paul had been responsible for organizing another, more convincing argument.

For in 1924, Paul Whiteman had dropped the first “American”, “pop” masterpiece: “Rhapsody In Blue.” Of course he had help.

Lots of it.

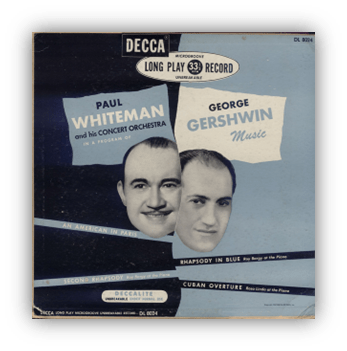

Paul’s primary talent was project management, aka getting other people to do all the work. In this case, he got George Gershwin.

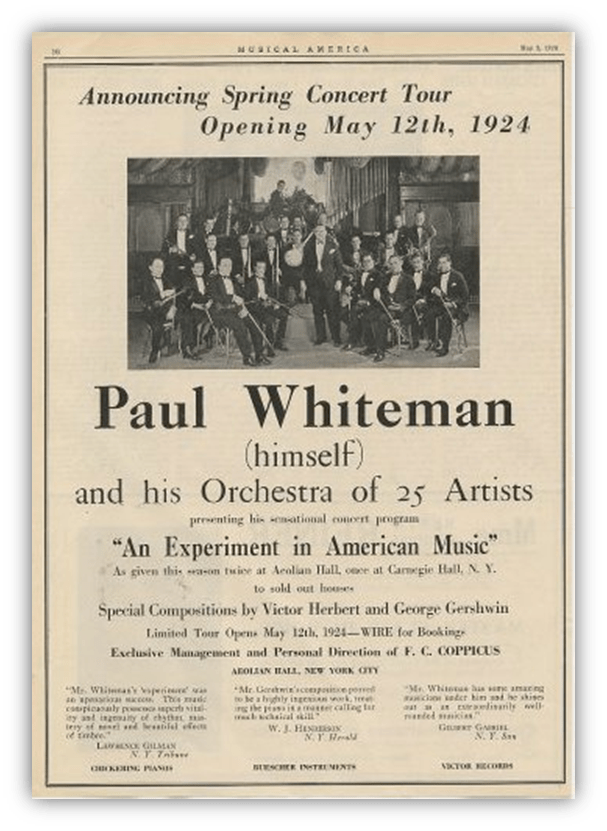

Paul’s other primary talent was self-promotion. Probably no composition in history, up to that point, had been marketed as heavily as “Rhapsody In Blue.” For “Rhapsody In Blue” was the climax to the most heavily promoted concert experience of the decade.

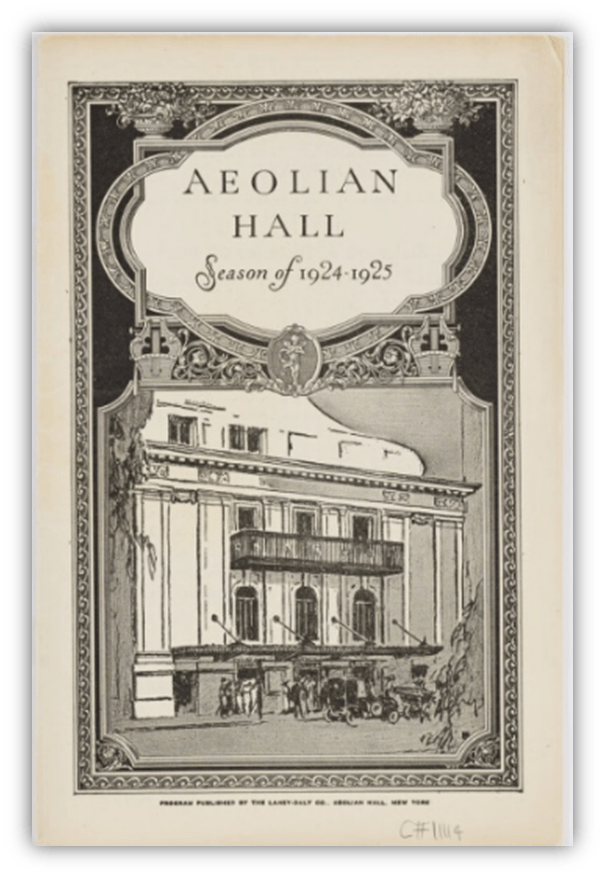

A pop concert, by a “jazz” ensemble, taking place, not in a swish hotel, as was the norm for a band of Paul’s status and temperament, but in the same theatre where classical music was played: The Aeolian Hall.

For a “jazz” band – a “pop” group – to play in such refined surroundings was outrageous enough… but Paul wanted it to be more than a concert. Capturing the spirit of the times – an era filled with scientific innovations and concepts such as theories of relativity that nobody understood – Paul’s show wouldn’t be just a concert… it would be an experiment!

He was even pompous enough to call it that: “An Experiment In Modern Music”!

It was all quite preposterous. Not to mention pretentious! Just the very thing that might get New Yorkers excited. Anyone who was anyone in New York was there, as well as a lot of New Yorkers who weren’t. Many of them had been personally invited: John Sousa, Victor Herbert, Stravinsky… the most unlistenable classical composer of the era, and therefore clearly a genius, and a European to boot! Russian, even!

Harlem stride-piano champion Willie “The Lion” Smith was in attendance, although Paul probably wasn’t cool enough to have personally invited him.

It’s not impossible that Paul went a little bit overboard with all of this because it was rumoured that his arch-nemesis – Vincent Lopez – was considering holding a similar “jazz is serious music now” concert.

It was clearly an idea whose time had come. And just like all the other amazing feats of the 20s:

- Flying solo over the Atlantic

- Inventing the Charleston…

- some guy called Shipwreck Kelly sitting on top of a pole for 12 days straight…

…Both Paul and Vincent wanted to be first to prove that “American music” was just as good as the imported stuff. The race to write and perform America’s first musical masterpiece was on! A masterpiece that would be performed, for the very first time, on Lincoln’s birthday! How American was that!?!?!!?

Whilst Paul considered himself the right man to put a production like this together, he was not delusional. He knew he couldn’t write America’s first musical masterpiece. But he knew someone who could! He knew George Gershwin! Paul Whiteman quite liked a Gershwin tune! He’d already had a hit record with one; “Do It Again,” a jaunty Dixieland romp (it’s a 7)

There was just one little problem. Paul had forgotten to tell George…

The story goes that George, and his brother Ira, were playing pool on a Friday afternoon. Or at least George was playing pool. Ira was reading the New York Daily, when his eyes spotted one sentence especially pertinent to his – or at least his brother’s – interests.

A sentence that claimed: “George Gershwin is at work on a jazz concerto that will be featured in the concert.”

But George wasn’t at work on a jazz concerto to be featured in the concert. This was the first he’d heard of it. Well, that’s not entirely true… Paul had asked… and George had politely said no.

But, as you may have surmised by this point, Paul Whiteman wasn’t often said “no” to. It’s possible that he no longer understood the concept. When George said “no”, Paul heard “maybe,” and when Paul heard “maybe” his brain decided that meant “yes.”

But now that it was in the newspaper, George felt that he had no choice. Now he had to write the damned thing. And he only had a month to write it.

Which, to be honest, sounds like an ample enough time. But then, I’ve never had the responsibility of composing the first American musical masterpiece dumped onto my lap.

By the time the big night came around, George wasn’t even sure his masterpiece was finished. But what could he do? The show must go on.

And the show did go on… and on… and on. As probably should have been expected from a concert calling itself “An Experiment In Modern Music”, the whole production had not been designed with a good time in mind. Paul had gathered all of New York into one place, and then bored them senseless with:

- (a): a lecture that promised that the concert would be “purely educational”, before launching into

- (b): hours of music broken up into sections with such snore-worthy titles as “True Forms Of Jazz” and “Contrast: Legitimate Scoring vs Jazzing.”

The distinguished guests were getting restless.

After hours of this stuff, it was finally time for George to play his much-hyped masterpiece. The masterpiece that he had written in a hurry and hadn’t even really finished yet. A masterpiece with a title only slightly more promising than what they had already sat through, based as it was on the titles of Whistler paintings.

(You may know Whistler’s Mother as Whistler’s Mother, but its actual name is Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1.)

Fortunately for everyone involved, “Rhapsody In Blue” was more attention-grabbing than its unpromising title, and woke the audience out of its slumbers. Henrietta Straus in Billboard a few months later said that the tune was “worthy of a Tchaikovsky” (“Dance Of The Sugar Plum Fairy” is a 10) and called it “a new chapter in our musical history.”

The Brooklyn Eagle, published five days after the event, said that it was already being “hailed by certain discerning critics as a significant piece of American music.” I’m sure Paul Whiteman would have counted that as a win: his hypothesis had been proven!!!

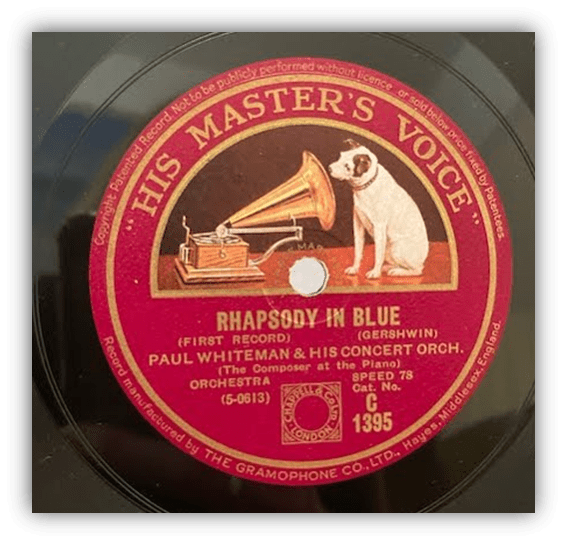

Given all the publicity surrounding Paul’s “Experiment in Modern Music” – and all the nice things people were saying about “Rhapsody In Blue” – you might have expected Paul and his band to have rushed to the Victor studios to record a version straight away. But no. It took months.

The “Experiment” took place in February. “Rhapsody In Blue” didn’t get recorded until June. And then there were several more months before it was finally released in October. Not sure why, but it must’ve had something to do with the fact that it was just so long!!! There were probably logistical issues surrounding the supply of so much shellac!!!

Promoted with the claim that it featured the “composer at the piano” – thereby adding to the sense of classical decorum – “Rhapsody In Blue”, the record, came in two parts – on both sides of the disc – for a grand total of nine minutes. By 1924 standards, this was an epic. It was most likely the longest record the vast majority of Americans had ever owned.

The 1924 recorded version of “Rhapsody In Blue” sounds little like any version you have ever heard. All the versions you’ve heard have – I’m assuming – been performed by a symphony orchestra, or such like. The 1924 version was performed by a Dixieland-style jazz band pretending to be a symphony orchestra whilst simultaneously featuring a dangled frying pan as a percussion instrument. The 1924 version begins, in true Dixieland jazz style, with a clarinet that sounds like a laughing hyena with a bone stuck in its throat.

If you’ve never knowingly heard “Rhapsody In Blue”, believe me, you have. As you listen to “Rhapsody In Blue”, you’ll – almost certainly – experience multiple moments where you go: “oh, this song.” And then again: “oh this song”. And you’ll be amazed that one composition can include so many instantly recognisable bits! Not to mention capture so many different and distinct moods. But of course it did. It had to. “Rhapsody In Blue” had to capture the entirety of America!

As George himself put it, “Rhapsody In Blue” was a “a musical kaleidoscope of America, of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our metropolitan madness.” Which might be more hyperbolic than anything that even Paul could have said!

“Rhapsody In Blue” is a 10!

Meanwhile, in Dirty-Blues Land:

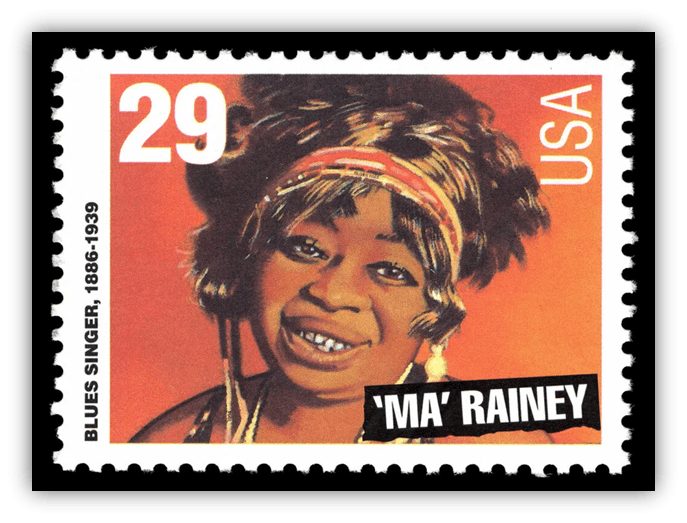

“Shave ‘Em Dry Blues” by Ma Rainey

Ma Rainey was marketed as “The Mother Of The Blues”, which was a nice way of saying that she looked old. Although to be fair, she very much was.

Ma Rainey had been singing the blues since 1902 when she had heard a girl singing a strange sounding song about the man who had left her. Like the guy at the railway station in Mississippi, playing a guitar with his knife, that W.C. Handy stole his version of the blues from, we will never know who that girl was. The girl didn’t call it “the blues” though.

Ma says she invented that. After repeatedly being asked what that strange music was that she was singing, Ma eventually started replying “It’s the bluuuuueeessss!!!!”

Since that day in 1902, Ma had been singing the bluuuuueeessss all over the South for twenty-odd years… by the end of the 1910s she was one of the biggest blues stars in The South, headlining The Famous Alabama Minstrels featuring “The Famous Dusky Beauty Chorus”, who promoted themselves as “The World’s Largest Coloured Show”! They travelled around The South in a “BIG waterproof TENT theatre!” They claimed to have “More Singers, Dancers, Comedians and Contortionists than all (the) others combined!”

When Paramount Records:

…a side hustle for a Wisconsin chair company called the Wisconsin Chair Company …

…decided to enter the blues market, and with Bessie Smith – the biggest blues singer of her generation, Ma Rainey’s protégé, and alleged kidnap victim, Ma and Pa Rainey having stuffed her into a burlap bag a decade prior, so desperate were they to have Bessie on their show – already snatched up by Columbia, signing Ma Rainey was a no brainer.

Ma very clearly wanted to make records. At her shows, she would make her grand entrance by stepping out of a big, fake Victrola. It was quite the entrance. Before the big reveal the audience would start chanting “The Phantom… The Phantom” and Ma would start singing, from inside the Victrola, until she finally stepped out, and – here I quote from Ruby, one of Bessie Smith’s girlfriends, from the Bessie Smith biography, “Bessie” – “the people screamed… she was that ugly!”

Or maybe it was because they’d never seen anyone wearing so much money before. Ma Rainey wore a necklace made up of five-, ten- and twenty-dollar pieces!

“Shave Em Dry Blues” sees Ma Rainey looking around, feeling a little puzzled. There’s one thing in particular she doesn’t understand: why a good-lookin’ woman likes a workin’ man… hey, hey, hey, daddy, let me shave ‘em dry…

Having read that last line, you yourself may be feeling puzzled. I mean, what does “shave ‘em dry” mean?

So for those of you not familiar with the proto-jive speak of the 1920s, “shave ‘em dry” means sex without foreplay, perhaps a little quickie in a dark alley.* Quite appropriately then, “Shave ‘Em Dry” sounds rough and raw – just Ma and two guitars – just like its subject matter.

Ma Rainey liked having sex. Usually with women, as was made obvious a few years later, when she was arrested in Harlem for having an orgy with multiple ladies. The police had busted her after a noise compliant. Given how happening Harlem was in 1925, they must’ve been making quite a noise. Bessie Smith had to bail her out.

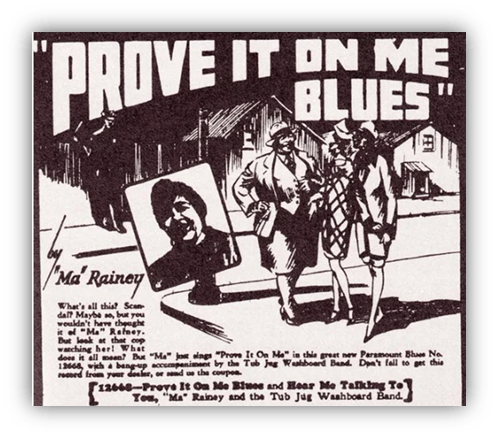

Maybe it was this experience that inspired “Prove It On Me Blues”, Ma’s big come-out song of 1927, with the misleadingly named Tub Jug Washboard Band. Misleadingly named, because there’s clearly also a kazoo.

In “Prove It On Me Blues” Ma is out on the town, as was her want. Ma is dressed like a man, as was also her want, rockin’ a collar and a tie. She’s out with a group of her friends. These friends, Ma informs us, “must’ve been women, cause (she) don’t like no men.”

Ma isn’t only wearing a collar and tie in the Chicago Defender – Chicago Defender being the second-best-selling Black newspaper in the country – print advertisement for “Prove It On Me Blues”, but a waistcoat as well – plus a jaunty hat! – whilst standing on the corner talking to a couple of slender flappers. Or as she puts it: “talk to the gals, just like any old man.”

“What’s all this?” the advertisement reads “Scandal? Maybe so, but you wouldn’t have thought it of Ma Rainey.

“Really? I’m pretty sure we expected nothing less?”

“But look at that cop watching her? What does it all mean?”

What indeed? (“Prove It On Me” is an 8)

“Shave ‘Em Dry” is also an 8.

* If you are thinking that this is a little bit crude for the 1920s, well… ten years later, Lucille Bogan would release a version, one that has gone down in the history books as one of the rudest and crudest songs of all time! A song that starts with the immortal lyrics “I got nipples on my titties, big as the end of my thumb.” And that’s about the only line that’s printable.

Meanwhile, In Old Timey Land:

“Wreck Of The Ol’ 97” by Vernon Dalhart

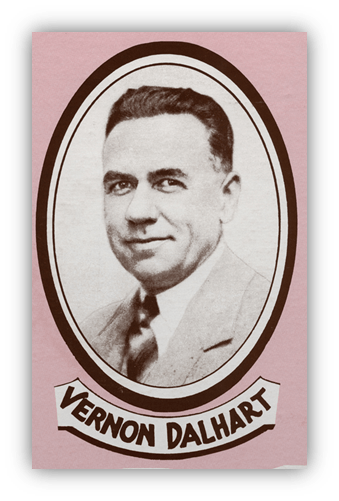

Vernon Dalhart wanted to be an opera singer. He also wanted to change his name. Not from Vernon Dalhart – which would have made sense, since that is a terrible name for a pop star – but to Vernon Dalhart.

From his birth name of Marion Try Slaughter.

Vernon – or Marion – was born on a Texas cattle ranch. Having no doubt tried slaughter – of cattle that is – Marion decided that it wasn’t for him. Sadly there were few career opportunities for opera singers in Texas at the time, so Marion – now Vernon – hi-tailed it to New York to try his luck there.

At least initially, Vernon had little luck. New York was full of aspiring opera singers, and Vernon was simply no good at it. Also, despite changing his name to disguise the fact that he was born on a Texas cattle ranch, Vernon sang opera with a Texas twang. Which would have been fine if Puccini ever wrote an opera about cowboys, but sadly, he never did.

Although Vernon wasn’t making the opera scene, he was at least making records.

Not hits exactly, but they must have sold adequately enough for Victor Records to keep on inviting him back. Finally, after about ten years, their faith was rewarded. Finally, Vernon had a hit. Two in fact, on the one record: “The Prisoner Song” and “Wreck Of The Ol’ 97”

“The Prisoner’s Song” was so called because Vernon’s cousin heard someone singing it when he was in prison. Also because the narrator is in prison, surrounded by cold prison bars, his pillow is a “pillow of stone.” He has this whole fantasy about being an angel, flying out of his prison cell, and into his darling’s arms, and… there’s only one way that a song this tragic can end… he dies. (“The Prisoner’s Song” is a 9.)

On its own, “The Prisoner’s Song” may not have been enough to become a prairie-wide phenomenon, but it was backed by a more newsworthy jingle: “The Wreck Of The Ol’ 97.”

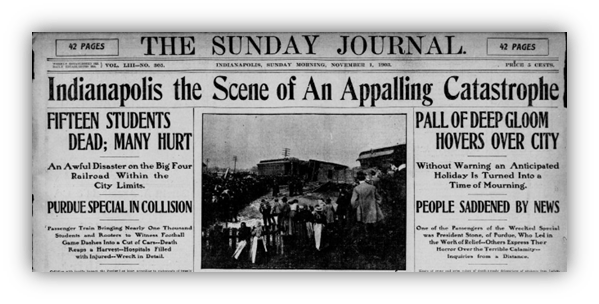

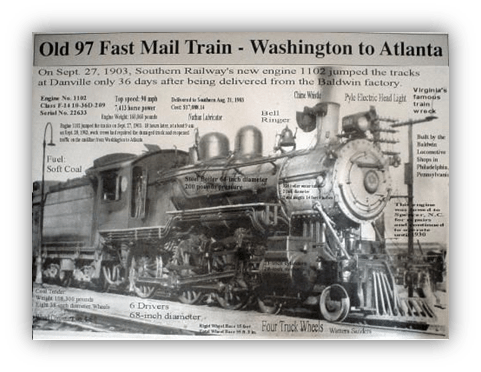

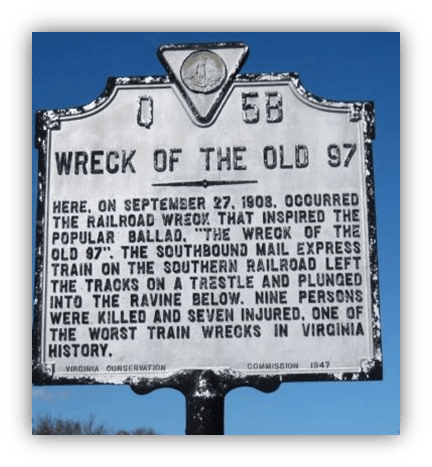

By the time “The Wreck Of The Ol’ 97” was recorded, the tragedy that inspired it was old news. Two decades old in fact. And it barely even registered as news at the time.

Train wrecks were so common at the turn of the century that the Old 97 had to compete with the Little Falls Gulf Curve crash of a month before and the Purdue Wreck a month later.

The typical newspaper seems to have squeezed in a couple of paragraphs about it, a week or two after the fact. Few papers outside of Virginia and North Carolina seemed to cover it at all.

“The Wreck Of The Ol’ 97” may never have become a song if not for a man with the suitably morbid name of David Graves George, the local brakeman, Town Marshall and amateur song writer, who was the first to arrive on the scene.

The way David tells the story, it went down like this:

Steve Broady, an engineer on the Old 97 – also known as the Southern Railway Fast Mail, a mail train that, in this case, was also transporting a case of canaries – was feeling a phenomenal amount of pressure at work.

The Old 97, you see, had a reputation to uphold, a reputation of always being on time. But not this time. This time Steve was running an hour behind.

Steve had to make that time up, even if it meant travelling at speeds far beyond those deemed to be safe. Even when travelling through the mountains, handling their hazardous curves.

Naturally the inevitable happened and the Old 97 took a curve too fast and plummeted into the ravine below, killing Steve and ten other men. The canaries were apparently fine, they flew away. Seven other men also came out alive, one of whom decided that he was getting too old for this shit and quit the next day. If “The Wreck Of The Ol’ 97” can be believed, Steve died “with his hand on the throttle, scolded to death by the steam.”

Vernon’s approach to such a tragedy was to turn it into a novelty song, complete with train whistles at appropriate junctures. It even begins with an almost cheerful and tuneful harmonica melody. Later, a delightfully tuneful whistle. It doesn’t sound as though Vernon is singing about the death of eleven men at all!

The most tragic part of this whole story? It appears that just before Steve (Vernon calls him Pete for some reason) got on that train, he and his wife had been arguing. So Vernon ends the story with a moral; women, don’t speak harsh words to your true love or husband, you never know if they will leave you and never return. This, and not the poor working conditions typical of the freight industry, is Vernon’s main concern. This is not a protest song.

After “The Wreck Of The Ol’ 97” hit, Vernon decided that this was what he was put on the Earth to do: sing topical story songs. He also decided to make the obvious strategic switch from singing about long-forgotten tragedies that nobody remembered, to singing about contemporary disasters taken straight from the headlines of that day’s newspapers. He basically became a singing news reader.

- There was “The Death Of Floyd Collins”, written by Rev. Andrew Jenkins to capitalize on the story of the death of Floyd Collins, a Kentuckian cave-explorer, stuck in a cave for more than two weeks, before dying of hunger, as America read – and listened to the radio – and waited.

- Vernon even recorded a tune called “The John T Scopes Case (The Old Religion’s Better After All)” all about the Scopes Monkey Trial, in which a high school teacher, John Thomas Scopes, was on trial for teaching evolution in a state – Tennessee – where doing so was illegal. Vernon took an anti-Scopes position and sold 60,000 copies of the record on the courthouse steps.

- When Charles Lindbergh flew solo across the Atlantic a couple of years later, thus becoming the most famous person in the world almost overnight, Vernon released the double-A-side “Lucky Lindy” / “Lindbergh (The Eagle of the U.S.A.)”.

Not to mention:

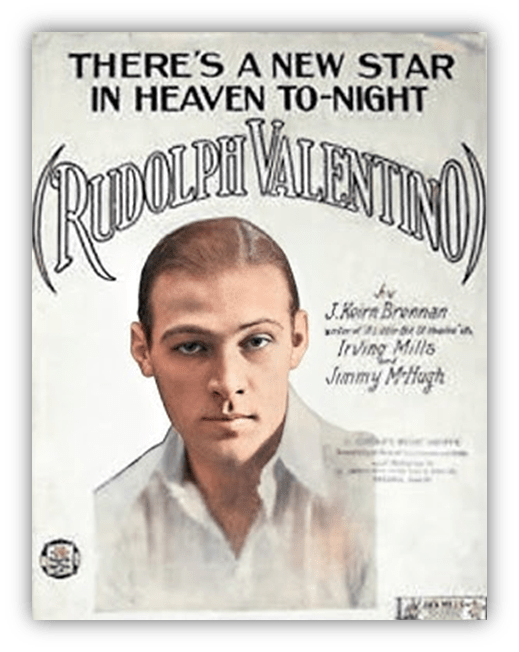

- “There’s A New Star In Heaven Tonight”, written and recorded in a rush, and released just ten days after Rudolph Valentino died. Just in case its subject matter wasn’t obvious enough the official title was “There’s A New Star In Heaven Tonight (Rudolph Valentino).”

None of these shamelessly-opportunistic-bandwagon-jumping-records sold anywhere near as many copies as Vernon’s initial quaintly moralistic tale about an obscure regional tragedy. It turns out you can sell news-bulletin-novelty records to all the people some of the time, or some of the people all of the time, but you can’t sell news-bulletin-novelty-records to all the people all the time…

I think Abraham Lincoln said that.

“The Wreck Of The Ol’ 97” is an 8.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Those Paramount blues records ads in the “Chicago Defender”, a presumedly other Black newspapers across the nation, and truly works of art.

Here’s “Black Snake Moan No.2” by Blind Lemon Jefferson!

“Black Snake Moan” is a classic blues, and now a standard at blues jams. Cover versions are still released all the time, a century later.

Paul Whiteman was a hustler. Whether that’s a compliment or not is in the ear of the beholder but if he had something to do with “Rhapsody In Blue” getting written, I’m all for it. Is there a better American piece of music written since we became a country?

That’s a serious question. Post your nominees for best American music of all time below. A few of mine are:

The dark unconscious parts of my mind say it’s “More Than a Feeling” by Boston. Laser-beam guitars, hand-claps, nostalgia, it sounds like the Fourth of July at the amusement park.

Lots of great detail reaching back into the pre rock n roll era. The names are familiar in the Paul Whiteman / Ma Rainey sections but this adds plenty more background material I didn’t know.

I only ever associated Gershwin with Rhapsody In Blue. Understandable given he wrote it. Had no idea that Paul Whiteman was so integral to it. Given everything you’ve said about Whiteman and from the other things I’ve read about him it seems he was a shameless self promoter. Wonder what he would make of the fact that his part in Rhapsody is largrly lost to history.

Is it synchronicity that Ma Rainey appears the day Cardi B appears for the first time on the #1s? Rude and crude is nothing new. It wasn’t new in 1924, going back through the centuries there have been plenty of generations and societies that were at it. Just not the puritans.

I didn’t realize that Whiteman had initiated “Rhapsody in Blue”. Interesting stuff!

Yes, crude and vulgar have always been around, terrifying the prudes. (Yours truly waves). Luckily “Rhapsody in Blue” remains better known.

This article brought to you by United Airlines.

I just watched the first three minutes of Manhattan. I miss pre-scandal Woody Allen so much. When he passes away, I’m going to rewatch all of his films in chronological order. I stopped at Blue Jasmine. Seven old films that will be new to me.

“Chapter one…”

Allen makes “Rhapsody in Blue” sound like the GOAT.

I can see what he was thinking with the name. The V and the D remind you of famous opera composer Verdi. And Dalhart conjures up those Italian names that start with D’. But at the time, you wouldn’t want to use a name that made it seem like you were actually Italian, so Vernon Dalhart still blatantly insists “I’m a regular American guy” while hinting of Europeanness and opera.