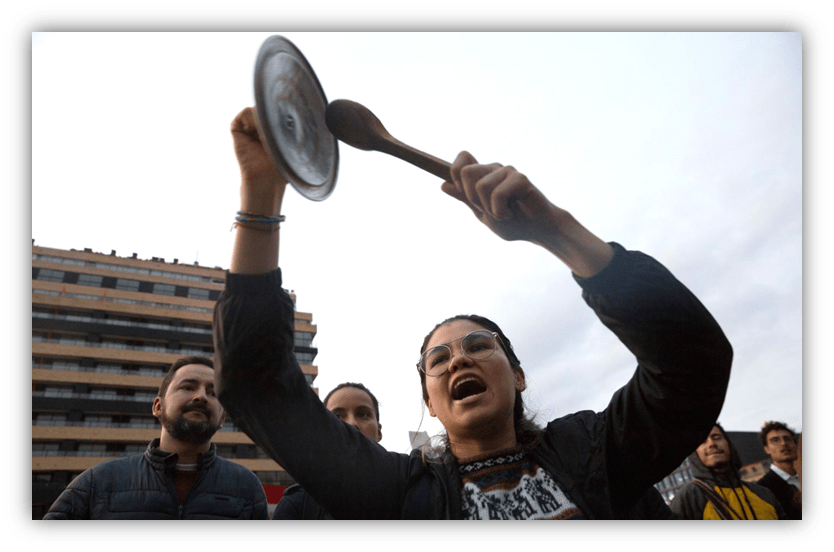

“Cacerolazo” is a Spanish noun.

It means: a form of protest where people make noise by banging pots, pans, and other kitchen utensils in order to make their displeasure known.

Because corrupt government officials need their beauty rest just like the rest of us:

It can be very effective.

It worked well in that least Spanish of countries: Iceland.

During the financial crisis of 2008 and 2009.

While the crisis was global, it hit Iceland particularly hard. In October 2008, Iceland’s three major banks — Landsbanki, Glitnir, and Kaupthing — collapsed due to risky lending practices. That led to countrywide economic turmoil. The government’s response, including the nationalization of these banks, didn’t restore public confidence. The value of the Icelandic króna plummeted. GDP plunging by over 30%. Unemployment soared.

Icelanders took to the streets, expressing their discontent by making noise with housewares. It became known as the “Pots and Pans Rebellion,” though some translations have it as the “Kitchenware Rebellion.”

It started with a single person.

Hörður Torfason is an activist, songwriter, playwright, set designer, actor, director, and poet.

He staged a one man performance in the park across the street from the Alþingishúsið, Iceland’s parliament building. He also invited passersby to step up to his microphone and speak their minds.

The following week, people arranged a larger protest and formed a group called “Raddir fólksins,” or “Voices of the People.” They decided to protest every Saturday until the government stepped down.

As a side note, a comedy TV show on New Year’s Eve is an Icelandic tradition. It’s called “Áramótaskaupið,” or “The New Year’s Lampoon,” and is usually the most watched show of each year.

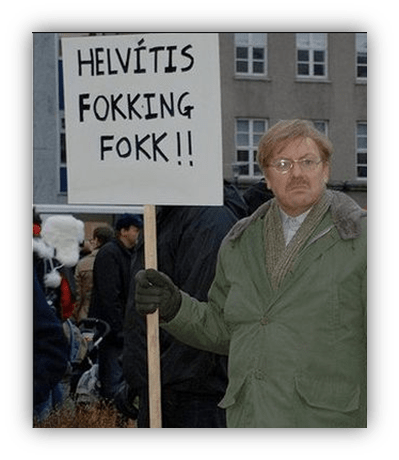

After weeks of protests, the show did a sketch about an uptight guy trying to decide what to write on his protest sign.

He came up with “Helvítis fokking fokk!!”

I won’t trouble sensitive readers with the translation but, yes, those are F-words. The phrase has become a popular saying and is still used in protests today.

The protests intensified in January 2009, with hundreds gathering outside Alþingishúsið.

Demonstrators demanded the resignation of government officials and new elections.

On the 20th, over a thousand people were met by riot police who used pepper spray. The next day, three thousand people showed up, to throw snowballs, eggs, and more at the building and the prime minister’s car. Police responded, escalating from pepper spray to tear gas.

It was the first time tear gas had been used in Iceland since the anti-NATO protests in 1949.

The demonstrations continued on the following day, which led Alþing, the Icelandic name for parliament, to schedule new elections for April, and for Prime Minister Geir Haarde to say he wouldn’t run due to his cancer diagnosis.

That wasn’t good enough. The noisy protests continued.

Haarde stepped down the following day and a coalition government was formed by the liberal and progressive parties. When new elections were held in early April, those parties gained seats.

The conservative Independence party lost a third of theirs after 18 years in power.

The new government put in place a combination of stricter banking regulations, aggressive fiscal policies, economic diversification, and a move towards renewable energy and technology. These policies were painful in the short term, but stabilized the economy and prevented a complete collapse.

That’s not to say the recovery went completely smoothly. Inflation, rising living costs, and economic inequality persisted, but the overall trajectory has been one of remarkable rebound. By the mid-2010s, Iceland was a success story.

Today, Iceland’s economy is more diversified and robust, and the lessons learned from the crisis have influenced financial regulatory practices around the world.

That is, when national leaders are able to learn by example. Some aren’t.

Iceland wrote a new constitution, and in a groundbreaking way.

In 2010, a lottery chose 950 individuals to represent a broad cross-section of society. These representatives discussed constitutional reform and came up with ideas for what the new constitution should include. This was an effort to ensure that the constitution reflected the will of the people and not just the political elites.

A Constitutional Council was then established in 2011 to draft the actual text of the new constitution.

This council consisted of 25 lawyers, academics, and others with relevant expertise, who were elected by the public.

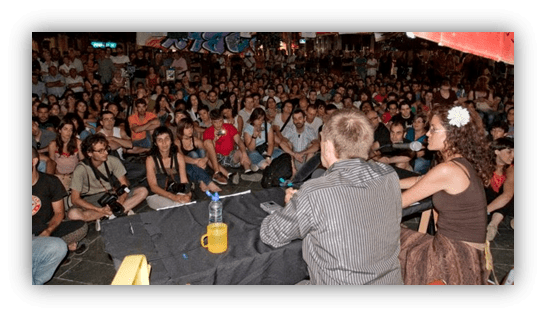

The council worked closely with the national assembly and used social media to connect with the public. They relied on feedback from citizens, allowing people to suggest changes to the draft as it was being written. This unprecedented level of public engagement and transparency was a key feature of the process.

After a year of deliberations, the Constitutional Council presented the final draft of the new constitution in 2012.

The draft strengthened civil rights, created greater transparency in government, boosted environmental protections, and established stronger checks and balances within the political system.

The proposed constitution was put to a public referendum in 2012. However, while the majority of voters supported the draft, the Alþing did not fully adopt it. This led to frustration among many citizens, as they felt their input had been disregarded.

Still, the Icelandic Constitution drafting process and its emphasis on citizen participation is a landmark in democratic reform.

Although the final adoption was delayed, the process itself has been praised as a model for direct democracy and public involvement in constitutional change.

During that process, a group of artists, activists, and community organizers came together in Reykjavík.

They wanted to honor the legacy of civil disobedience that had been part of Iceland’s foundation since its early days. With both historical events and the recent Pots and Pans Rebellion in mind, they envisioned a permanent public artwork that would serve not only as a reminder of past struggles but also as a guidepost for future steadfastness.

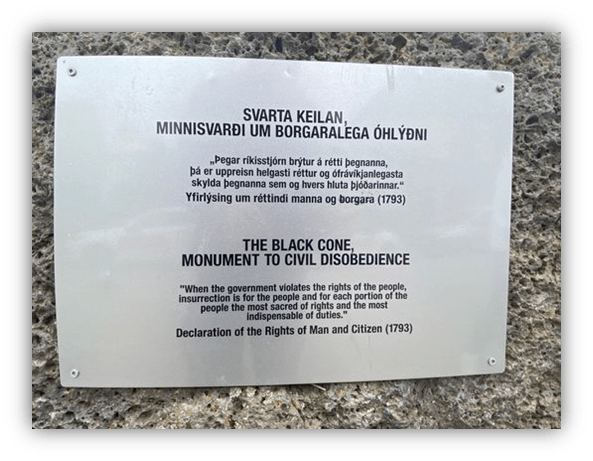

They chose a simple design created by Spanish artist Santiago Sierra that reflected the very essence of Iceland:

A simple black cone splitting a rock. It symbolizes the volcanic origins of the land as well as the resilience and determination of its people.

The idea was a little controversial. Critics argued that a monument to civil disobedience might encourage lawlessness, while supporters maintained that nonviolent resistance was a vital aspect of democratic life. Conservatives said that while civil disobedience is sometimes necessary, it should not be romanticized to the point where it undermines the rule of law or encourages disorder.

Others, however, saw the need to remind citizens of their rights and the importance of standing up for what they believe in –

And to warn leaders, who might be thinking of abusing their power, that the people are watching.

Workshops were held across the country, where the design was refined through a series of public consultations. This participatory process helped ensure that the monument resonated with a broad spectrum of Icelanders.

Over months of debate in public forums, art collectives, and local councils, the final design gradually won acceptance.

It was seen as a necessary counterbalance to decades of political centralization and environmental exploitation — a visual rallying point for those who believe that peaceful protest can change society.

Granted, throwing snowballs and eggs isn’t exactly peaceful, but it’s not terrorism. Sometimes banging on pots and pans can be enough. There’s no need to beat capitol police officers with flagpoles or threaten to hang elected officials.

The monument’s construction was a community effort. Local artisans, engineers, and volunteer workers from across Iceland came together for the project. It’s a piece of art that was by the people, for the people.

Sierra provided his work for free on the condition that it remain across from the Alþingishúsið in perpetuity.

Initially, it was directly across the street from the front door but has since been moved 90 feet to the southwest corner of the park. It’s a more accessible location and gives a little more protection from the elements.

Since its unveiling, the Black Cone Monument has become a site for demonstrations, cultural festivals, and academic discussions.

- Activists have gathered around the monument to hold vigils, protests, and public forums.

- School groups and university classes visit the site to learn about Iceland’s history of civil disobedience.

- Local bands and performance artists have used the space around the Black Cone as a venue for free concerts and public art installations.

For foreign visitors, it’s a glimpse into a culture that values both tradition and change, a culture that has learned to harness the power of dissent in pursuit of a better future. It has become an iconic symbol for those who dare to challenge authority in the name of justice, environmental stewardship, and the preservation of democracy.

Leaders, even democratically elected ones, can be forgetful.

The Black Cone reminds them who they work for.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Up

Great post, Bill!

(and I like the post page revamp, mt)

Some recommended reading for worried Americans:

Blueprint for Revolution: How to Use Rice Pudding, Lego Men, and Other Nonviolent Techniques to Galvanize Communities, Overthrow Dictators, or Simply Change the World

By Srdja Popvic

Some great ideas to chew on, and hopefully use, in the months and years to come.

Cosigned, this was an inspiring read. Gives me hope.

Thanks, Phylum, for noticing… Those of you who visit our site on desktop and tablet got a little sneak preview today of a new tweak or two. Feedback is welcome.

I knew parts of this and have seen the Black Cone on a visit to Iceland but this ties everything together and fills in the gaps. Nicely done.

I wonder does the culture and demographics of Iceland make it easier to generate a more impactful rebellion. A small population, with a third of them living in Reykjavik makes it simpler to mobilise. It also seems a lot more accessible, from what I remember anyone can walk upto the parliament building. It all seemed much more relaxed and that small population can make for a more cohesive community where it’s easier to work to a common goal.

It’s an inspiring story offering hope that the people can effect real change but transferring that to other countries may not be so easy.

I hope to see the Black Cone when I’m in Iceland for 23 hours next month.

You’re absolutely right. In this case, smaller is better, but it’s still an example of what can be done when people pull together. In larger countries, like my own, protesters will have to get more creative to be heard.

The funny thing though is that people think of their government as “them.” Now wait a minute, are they aliens from another solar system? No, they’re “us,” our neighbors. They’re not the enemy, they’re just the wrong people for the job. We need to hire better people.

Problem is persuading sensible, thoughtful people that would be right for the job to apply.

How about government on a rota basis where people are called up from all backgrounds via a lottery? Take out all the vested interests and those in it just for ego trip of holding power. Government literally by the people and for the people, certainly no more us and them. And if one cohort turn out to be a bust they only get a year before the next lot are called up.

Almost makes me want to move to iceland!