Bill never comes up short.

First things first:

Wrocław is a city in Poland. And it’s not pronounced RO-klaw.

In Polish, W’s sound like V’s and the Ł with a slash through it sounds like a W. So the city’s name is pronounced sort of like VRAHT-swav.

Say it with me now:

“Wrocław.”

When you walk around the city center, you start noticing little statues.

Of dwarfs.

Some are out in the open, others are a bit hidden. They may be on the ground or on a stairway or over a door. Anywhere.

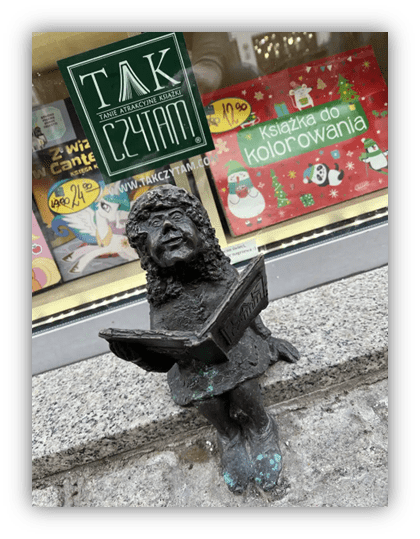

Many are themed on their location. There’s a butcher dwarf outside a meat shop, a baker dwarf outside a bakery.

And another on the window sill of an ice cream shop offering you a small cone.

Many of the dwarves seem to be tipsy.

They’re just enjoying life.

There are over 800 of these little statues and more are being added all the time.

They’ve become such a tourist attraction that you can go to the Dwarf Info shop, buy a map of all the statues and their locations, and go searching for them all.

It’s a fun way to see this beautiful city.

You may well ask why these statues started appearing. It’s not a simple answer, and we have to look at Polish history to get a clear picture. Pull up a chair, grab a beverage, and I’ll tell you about it.

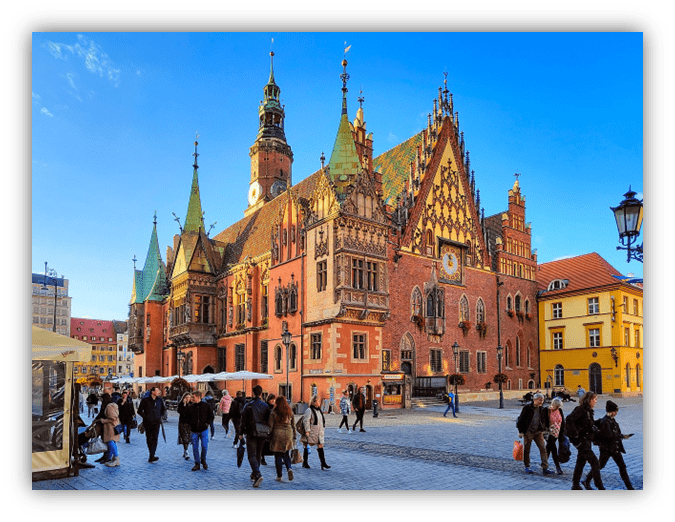

Wrocław is in the Lower Silesia region of southwestern Poland.

It’s been a city, under various names, for centuries. For a while, it was called Breslau and it was in Germany because borders have a way of moving. We don’t know when they started building the Ratusz (City Hall), but the restaurant in its basement has been operating since 1273.

I won’t go into the city’s entire history here. We’ll just pick up its story in the 1970s.

Following WWII, Poland had a single political party, and that party was the Polish United Workers’ Party, AKA the Communist Party.

For all of the 1970s, Edward Gierek was the Party’s First Secretary.

He took out loans from other countries with the idea that the money would help increase production.

Instead, Poland slipped into a recession. It was so bad that food and basic goods were rationed.

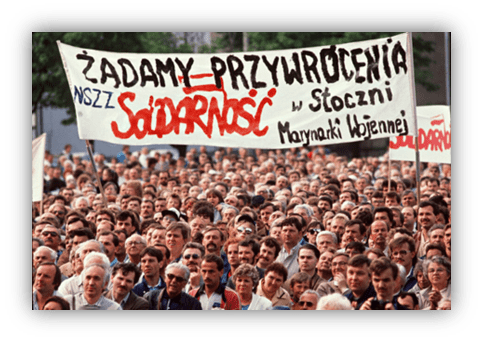

The backlash was strong. Workers at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk started a union. Known as Solidarność or Solidarity, it was the first trade union in the Communist Bloc. Its leader, Lech Wałęsa, would later become Poland’s president, but that’s getting ahead of the story.

In response to the backlash, Gierek was put under house arrest and was replaced by the more extreme General Wojciech Jaruzelski, who almost immediately imposed martial law. That was on the 13th of December, 1981.

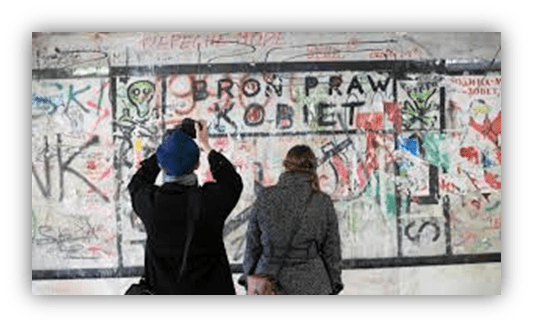

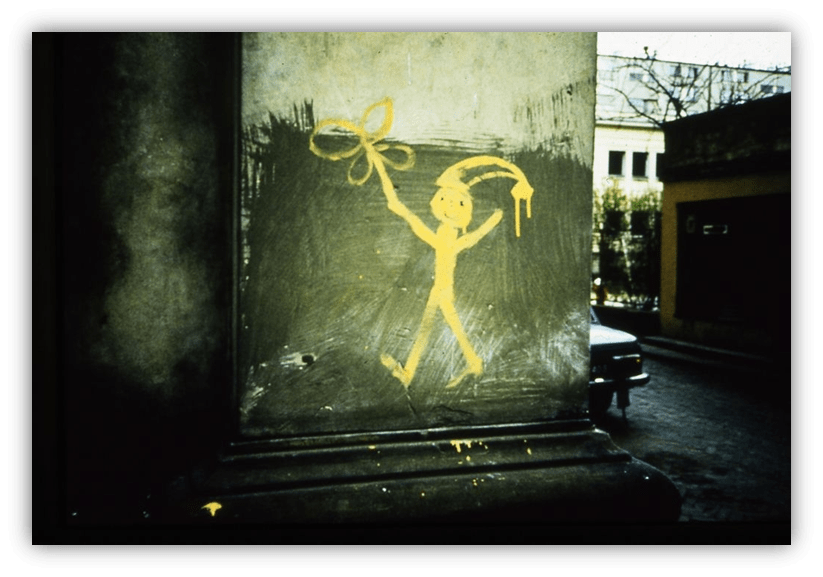

Anti-government, anti-communist, and anti-Jaruzelski graffiti started appearing all over Poland.

Government crews would paint it over as quickly as it went up, and then more graffiti would show up. It went back and forth between the two sides. Graffiti, cover-up, graffiti, cover-up, and so on.

At least paint sales were good.

A former student activist at the University of Wrocław, Waldemar Fydrych, thought that the back and forth was silly.

So he decided to make it sillier.

Instead of putting up more graffiti, he formed a group called Orange Alternative and, among other activities, they painted dwarves wherever graffiti had been covered up.

This did two things.

- If the government painted over the dwarves, they’d look ridiculous. After all, who’s scared of a cute little dwarf? And yet anyone tuned into the resistance knew that there was some anti-government sentiment just behind the dwarf.

- The more the graffiti was covered over, the more dwarves appeared. These little paintings showed just how much solidarity there was against the Communists without coming out and saying so.

Fydrych wrote in his Manifesto Of Socialist Surrealism that the government had become so absurd that it was a work of surrealistic art, much in the way that the performative nature of today’s culture wars is not far from performance art. He therefore took inspiration from the surrealist movement in 1920’s Paris — Dali, Magritte, Ernst, et. al. — to make fun of the government through nonsense art.

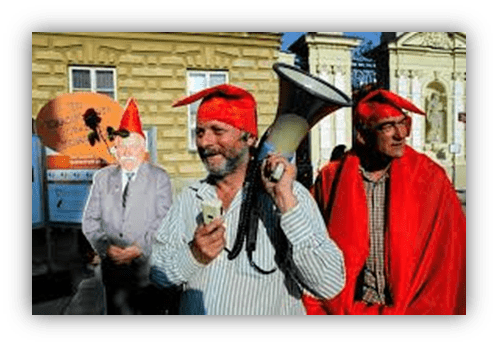

Orange Alternative held over sixty art happenings in various cities around Poland.

They said nothing overtly political or angry — in fact, it was all good clean fun.

But handing out free toilet paper and food in a time of rationing was a political statement, even when done under silly mottos like “There is no freedom without dwarves.”

Especially when they were all wearing pointy orange hats.

The bright colors and tomfoolery of it all attracted huge crowds and newspaper reporters.

Even though the government arrested many people, they looked weak and petty carting away 80 people dressed like Santa Claus.

“Can you treat a police officer seriously,” Fydrych said, “when he is asking you: ‘Why did you participate in an illegal meeting of dwarfs?’”

A dwarf is just a dwarf until it becomes a symbol. Then it’s a giant.

At some gatherings, they sang songs about loving the police. How can a cop arrest someone singing that sort of song? And when the police did make arrests, they’d thank the police for not discriminating against dwarves.

When the dwarves handed out free pretzels during a food shortage and were arrested for doing so, they showed the government’s frailty.

The Party knew it was doing a terrible job and was sensitive to criticism, even criticism disguised as friendly gestures like giving your fellow citizens pretzels.

The government was baffled by Orange Alternative, as were most people.

Everyone knew they were making a point, but no one knew quite what it was. That’s the genius of surrealism.

It’s whatever you think it is, a Rorschach test you take yourself, but you can never be sure you’re right.

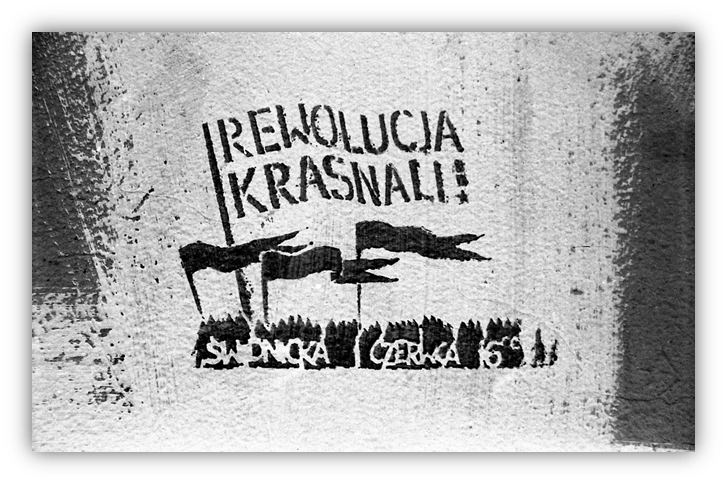

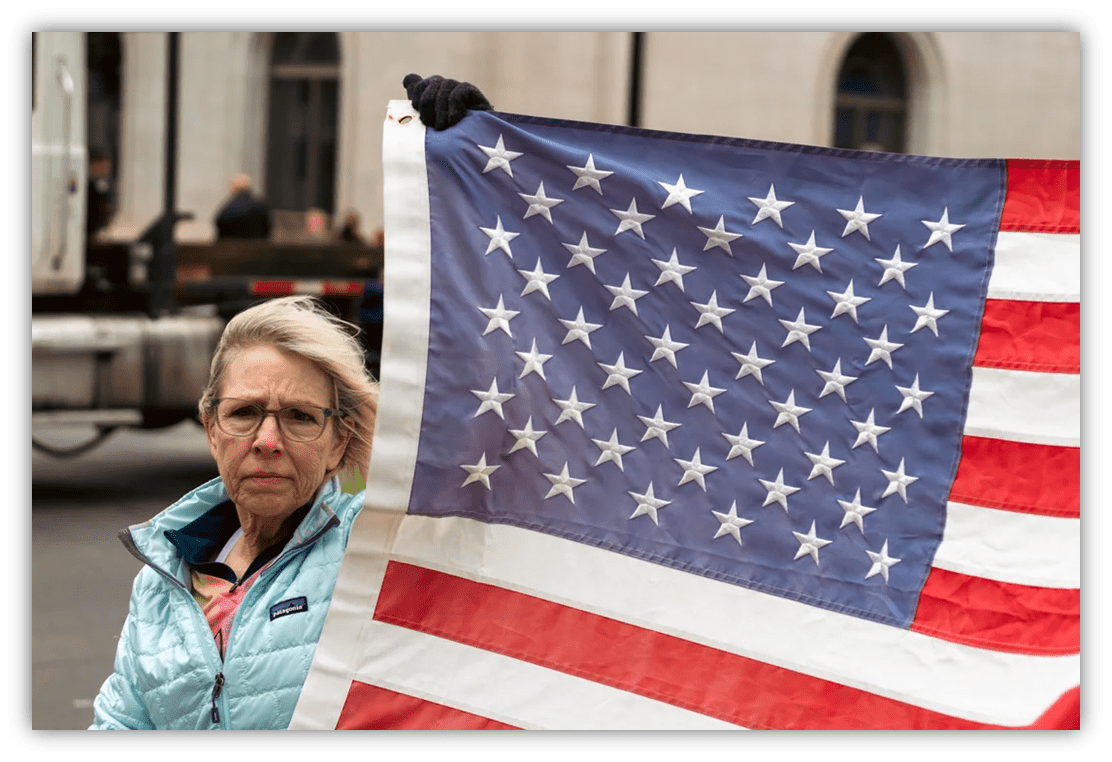

Orange Alternative had its biggest happening, on June 1, 1988.

It was called the “Revolution of the Dwarves.” 10,000 people marched through Wrocław wearing pointy orange hats. Other cities held similar events on the same day.

Whether they had any real effect on the Party’s downfall is questionable. But in April of the next year, the communists gave up exclusive power and a relatively free and open election was held.

The Party lost in very large numbers to Solidarity candidates.

Orange Alternative disbanded at the same time. Maybe their work was done.

In 2001, a statue of a dwarf was erected to honor Orange Alternative.

Standing on the corner of Świdnicka and Kazimierza Wielkiego, this first statue has been nicknamed Krasnal Papa, or Papa Dwarf.

There were no plans for any other statues.

Two years later, a plaque was placed at the Dwarves’ Museum by Wrocław’s mayor, Stanisław Huskowski. The plaque is at shin level. Unless you’re a dwarf, then it’s at eye level.

In 2005, a sculptor named Tomasz Moczek placed five dwarves around town, including these two on Świdnicka, unknowingly working against each other. It has all the humor and commentary of the Orange Alternative shenanigans.

His five statues were smaller and in a different style than Papa Dwarf. With beards, pointy hats, and a lot of detail, this is the style that caught on. All the statues from this point on would look like Moczek’s design.

The dwarves are popular with tourists and residents alike.

Locals even put little mittens and scarves on them in the winter.Businesses started asking for dwarves in front of their shops.

- If you pass a bookshop? Look around for a dwarf reading a book.

- If you spot a dwarf with a suitcase? See if you’re in front of a travel agency.

Some of the statues are to bring awareness to certain topics.

Like the blind dwarf with a cane.

Or this little guy in a wheelchair:

It must be hard getting around town on rough cobblestones.

And some dwarves have no deep meaning other than:

they’re fun.

At some point it was noticed that the dwarves were all male. There are now seven or eight female dwarves, and it’s likely there will be more.

What started as a subtle, subversive, and joyful protest has now turned into a cute, lighthearted, and joyful citywide art project.

It’s profitable, too, bringing in tourists who come just to count how many dwarves they can find.

As tributes to the work that went into ending communism, other cities have installed dwarf statues.

They’re in Lviv Ukraine, Berlin Germany, Kaunas Lithuania, and a few others.

I hope to see one on a trip I’m taking this month. If I do, it’ll be in my next post here on TNOCS.

A pleasant surprise to see the dwarves of Wroclaw featured here today. It’s one of my favorite places in the world, and the dwarves are both fun and an important reminder of history.

Enjoy your trip! Last time we were there was just after Christmas and there was a huge market in the town square with over 200 stalls. It was magical!

A place I heard about after the trip which I wish I knew about is a pub/restaurant called Konspira, which is also a museum of sorts, featuring lots of artifacts from the political protest days you wrote about. If you haven’t been there, maybe check it out and tell us all about it.

Książ Castle, not far from Wrocław, is definitely worth a visit. I have many others spots to recommend if you are interested, but maybe you already have a plan. Safe travels!

I’ll put both Konspira and Książ Castle on the list. Have you been to the Racławice Panorama? It’s an enormous 360 degree painting you have to go inside to see. Hala Stulecia, with its fountains and gardens, is spectacular, too.

The trip I’m taking next week isn’t to Poland though. You’ll just have to tune in to TNOCS to find out where I’m going.

I have been to both Racławice Panorama and Hala Stulecia. Both are fantastic.

I’ll be interested to see where you go. Travels with V-dog.

Thanks for educating and inspiring today, Bill! And putting a smile on my face, to boot.

Had no idea about the dwarves of

Wrocław – or the correct pronunciation for that matter.

Fascinating story behind them, harnessing the power of the surreal and silly and coming out the other side with something to put the town on the map.

I think they made the right call in tweaking the look of the dwarves. Papa Dwarf looks less mischievous and more the stuff of nightmares to me.