We must say more than George Floyd’s name

May 25 marked five years since the death of George Floyd, an African-American man restrained and murdered by a white police officer in Minneapolis.

Since that time, the United States has struggled to reckon with what made itself visible again in Floyd’s death. Today, we see it proliferating – often officially sanctioned.

Our collective unwillingness to discuss, let alone confront white supremacy is the elephant in the room of our society.

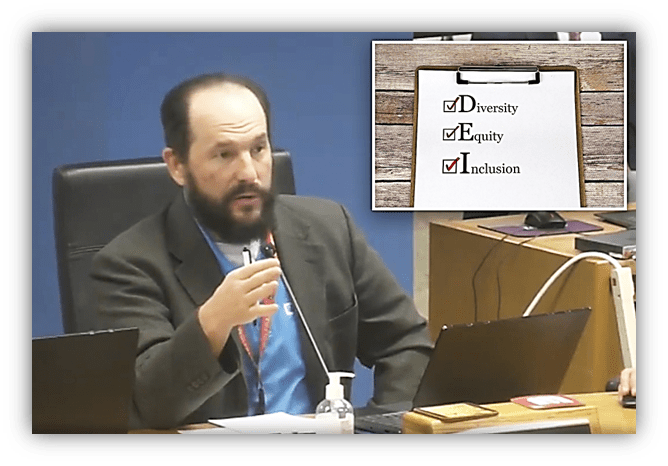

Consider the recent case of Sam Hershey.

Hershey is a member of the Wake County North Carolina Board of Education. He reacted in February during a board meeting to executive orders removing policies involving diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) from federal agencies, as well as notifications that funding would be removed from school districts that promote DEI initiatives.

“I think it’s really important to talk about people being hired based on their skin color, and for 250 years, it has been mediocre white men who have been hired based on their skin color.”

That comment went viral, as did a later statement:

“That’s the thing that drives me nuts the most, that people who throw around ‘DEI hire’ is that they’re just replacing the ‘N-word’ with ‘DEI hire.’ “

What the outrage machine lacked in its summaries was the fullness of Hershey’s statement.

Between those two sections he said this:

“ ‘Diversity, equity and inclusion’ ensures that our kids who need more help get more help. It ensures that our black and brown kids, who have not had the same educational opportunities over the course of the 249 years of this country, get those opportunities, and it’s without lowering standards.”

Never mind nuance. X, Fox News and the like made hay of Hershey soundbites.

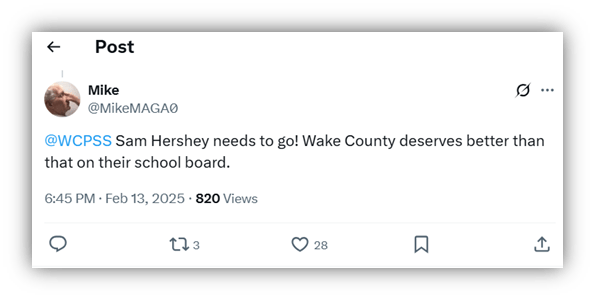

With predictable results.

Critics said Hershey should be removed from the school board. Others made personal insults, some of which were antisemitic.

Within days, Hershey told local media he regretted that both the comments and resulting response diverted attention from the potential impact of federal budget cuts on education.

As a white man of a certain age, I watched the Hershey story play out.

My first thought was, “Where was the lie?”

My second was that Hershey had reason to second-guess his statements, regardless of their merit. He got carried away as a public official in a public forum.

He took a risk that his statements might be disseminated and open to third-party manipulation.

And in this hyperfast, hyperpartisan age, he underestimated the degree and speed with which the tools of white supremacy were leveraged to put him in his place.

That’s what white supremacy does:

It assigns the relative positions of people in a hierarchy and exerts whatever effort is needed to reinforce rigid roles. Keep everyone in their place.

Five months before Floyd’s death, I joined a dozen or so people at my Catholic parish to take part in “Faith & Racial Equity: Exploring Power & Privilege:”

A series created by the national nonprofit JustFaith Ministries.

As COVID-19 moved our meetings from in person at our parish to on Zoom in our homes, this series and follow-ups on racial healing and racial justice helped me examine the relationship between my faith and our nation’s original sin.

Participants explored our own biases, histories, philosophies, and approaches to living.

We dug into history, sociology, political science, economics and more as we learned about our roles in this society.

We began to articulate how we could challenge the assumptions and legacies of white supremacy that we absorb like the air we breathe.

And then, as “Faith & Racial Equity” wrapped up, the nation reeled in the shock of Floyd’s death. We saw it on video, heard of his saying, “I can’t breathe.”

We’re at a place in U.S. history where once again we’re moving from covert to overt white supremacy.

Where whiteness, stereotyped masculinity, secular fundamentalism, and authoritarianism coalesce. But unlike the era preceding the Civil War, there are no geographic demarcations – only the contours of our own hearts.

There’s an adage in recovery that “we’re only as sick as our secrets.” If that’s so, the U.S. is in very bad shape.

Fundamentalist and authoritarian-leaning politicians are bent on compromising free speech, dismantling public education, and destroying the safety net of social services and laws aimed at keeping us healthy, educated, nurtured and safe.

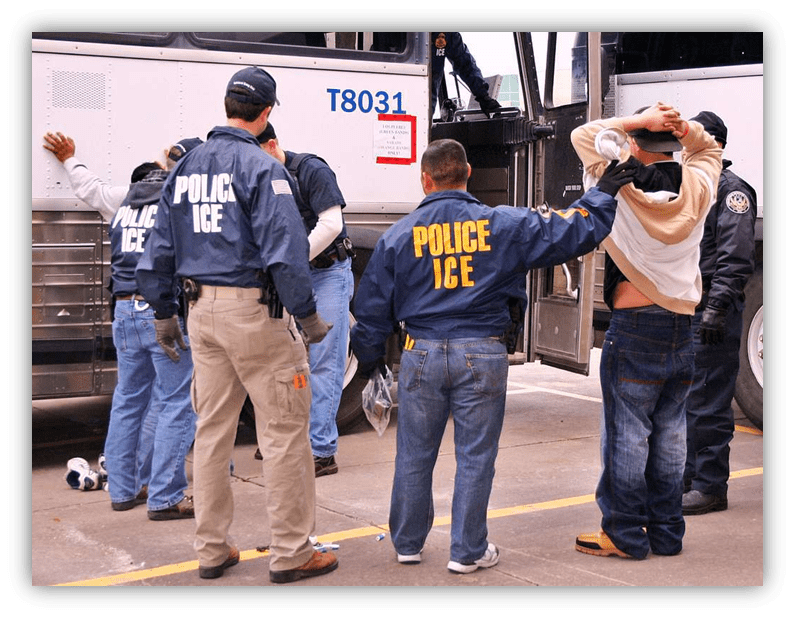

Government agents are rounding up people of color for expulsion without regard to civil liberties.

Meanwhile, our president has moved to welcome white South Africans (the ruling class under apartheid) as “refugees.”

We have been told that, somehow, it’s wrong not to be awake to the social, legal and economic inequities continuing to impact people of color.

And that teaching young people the facts of U.S. history is wrong if it leads them to feel uncomfortable.

The words “diversity,” “equity” and “inclusion” have become targets of derision.

As if the world truly is better by being homogenous, inequitable, and exclusive.

This discourse of dominance threatens us all.

As a college freshman, I thought I learned what it meant to escape the closet.

To acknowledge to myself who I was and to whom I was attracted. I couldn’t know it would take me a decade of speaking my truth, step by step, time and again, to avoid suffocating.

Yet it took me four more decades to realize that my coming out didn’t mean I had escaped the responsibility to demolish my white-supremacist mindset.

I had no inside track to understanding the oppressions people of color face in a white-supremacist society.

How can we honor George Floyd today?

By uniting and speaking up – not only his name but of the supremacist mindset that led to his death.

If not, our society may well follow him.

Let the author know if you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote.

Comments are welcome below.

So much truth here. And truth that we refuse to face. I have not been on here in several days because I have been participating in a prison ministry and have been off-line during that time.

The racial inequity of the justice system is staggering. And nobody wants to talk about it.

Coming up with a comment is difficult, which proves your point. I guess I’ve avoided the subject even in my own mind. This is going to require some introspection.

I think it’s just difficult to realize how things are unfair. Being the privileged caucasian, there are just things I don’t understand. They aren’t intuitive. I have to make an effort to understand them. The world is bigger than my bubble, and if I don’t make an effort to expand my perspective, I probably won’t change. Listening to my children, or listening to any youth, helps me change. They aren’t burdened with decades of pre-conceived notions like I am. But I just have to make a decision to be humble and teachable. Admit that all of these people crying about something might have a point that I need to learn. And, I’m not being high and mighty here…I know there’s a lot that I still do not get. But I’ll keep learning.

Maya Angelou said, “Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.”

Question your comfort, listen to other voices, and when you know better, do better.

Thank you, everyone, for your feedback. This was a difficult piece to write, but it’s been reverberating for months and I knew I had to give it a try. I guess part of the reason for the difficulty — other than a generic fear of being targeted by anyone who thinks white supremacy is the way to go — is trying to figure out next steps. In the end, all we can do is call out what we see and try in our own ways to respond differently.

DEI makes me want to scream. Did women voters not get the gist of the senator who sat in her kitchen to deliver the rebuttal to the former president’s last state of the union? Who do you think is at the top of the DEI list? One of Musk’s exes posted: “I love the patriarchy,” on social media.