Another in an occasional series on things that never fail to crack me up, for reasons I can never fully explain

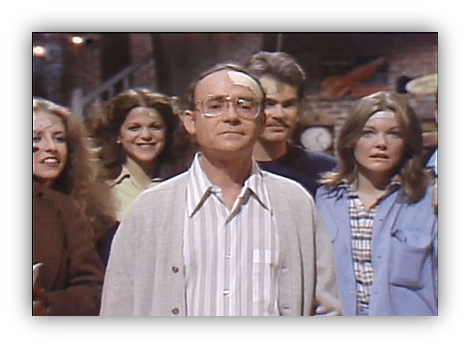

In the very early days of Saturday Night Live, the hosts, writers, and even the showrunner himself frequently deployed a kind of critical shorthand.

It was a way to dismiss any premise that didn’t quite fit the vision for such a new, hip, trailblazer of a show.

Host Buck Henry remembered wanting to rewrite an early sketch to give it a traditional ending, but SNL writers dismissed him:

“They thought somehow it was like Carol Burnett.”

Band leader Paul Shaffer recalled that even something as pedestrian as the closing credits had to avoid sounding “too Carol Burnett.”

And Lorne Michaels himself famously corrected director Dave Wilson for using the word “skit, explaining:

“We do sketches.

Skits are what Carol Burnett does.”

To the young rebels of SNL, The Carol Burnett Show represented everything they wanted to avoid:

Too broad… too formulaically corny… and at the top of the list: too willing to let performers break character and laugh at their own material.

Professional actors are taught from day one: never break character. The show must go on.

Stay in the moment. Keep the illusion alive.

But what happens when a performer deliberately sets out to destroy that very principle? Not by accident, but through calculated comedic warfare?

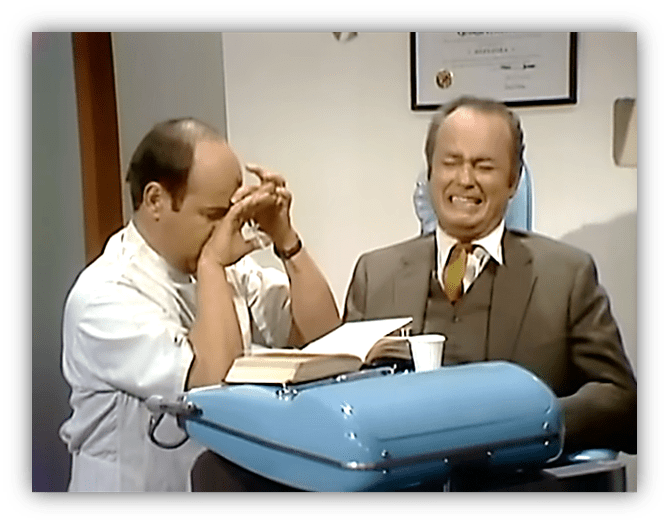

Enter Tim Conway and Harvey Korman in one of the most famous sketch breakdowns in television history.

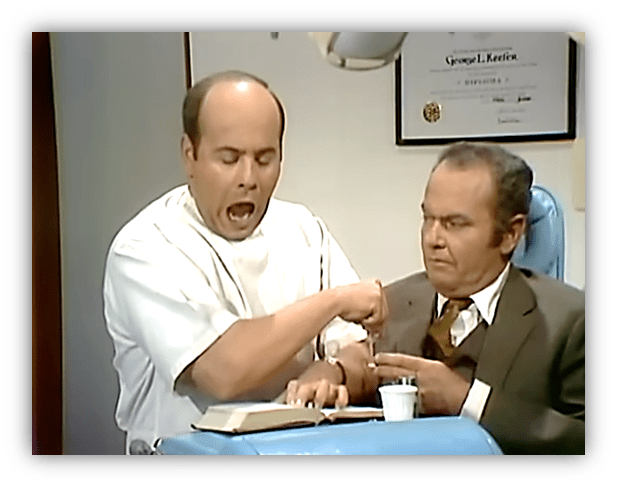

“The Dentist” from The Carol Burnett Show, originally aired on March 3, 1969.

Conway plays a fresh-out-of-dental-school practitioner treating his very first patient, played by Korman.

The sketch was inspired by Conway’s real-life dentist, who while still a student accidentally injected novocaine into his own thumb while working on a patient. As Conway explained:

“He numbed his own thumb and didn’t want to mention it to the patient. I did the same thing to Harvey.”

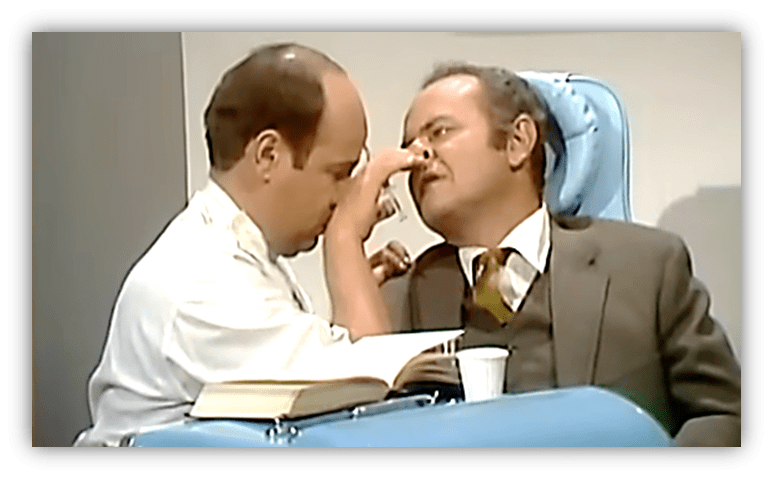

As the sketch unfolds, Conway’s bumbling dentist repeatedly injects himself with novocaine, each time affecting a different part of his body. His hand goes numb, then his cheek, and then his leg begins to give way.

All the while, he continues trying to work on Korman’s character with increasingly impaired motor skills.

Conway later revealed: “The idea of repeated accidental novocaine shots was a surprise to him; he hadn’t seen that part of the sketch until we were taping.”

That last part is crucial. Conway had weaponized a surprise.

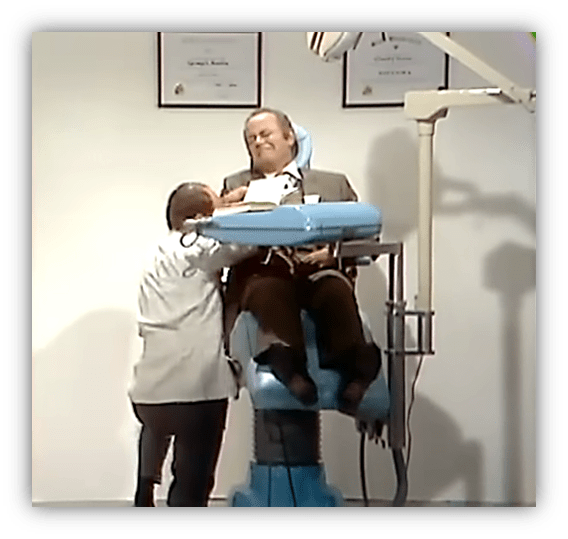

Picture this from Korman’s perspective.

You’re strapped into a dentist chair, in full view of a of a live audience. Your scene partner begins an increasingly absurd physical performance you’ve never seen before.

You’re supposed to maintain your role as an anxious patient, but Conway is suddenly going off-script – what’s next?

The moment when Korman first starts to crack is visible – a tiny smile creeping across his face as Conway’s debilitated dentist struggles to function. Conway then doubles down, his body becoming more grotesquely numb, and his movements more erratic.

Korman tries valiantly to stay in character. But it’s a losing battle.

His laughter starts as barely contained, and it’s pretty much downhill from there.

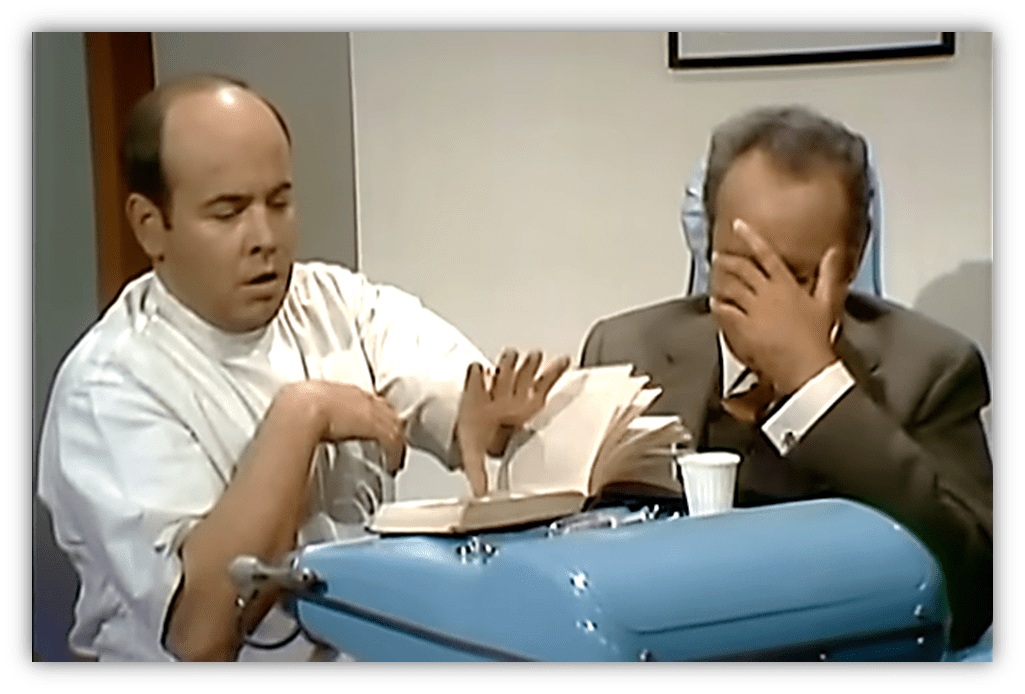

Conway, meanwhile, follows his plan with complete intention, never once acknowledging that he’s destroying his scene partner.

This wasn’t winging it or goofing around, it was deliberate. He knew exactly what he was doing every step of the way, following his own secret script. A meta-performance designed to systematically dismantle Korman’s composure.

As Conway later admitted: “My object was to find places in the sketch where I knew I could break up Harvey. I don’t think I ever missed.”

So: What’s So Funny About It?

Why does watching Harvey Korman completely lose his composure make me laugh? I think I know why.

The vulnerability is contagious.

- When we see a professional performer completely lose it, something primal happens.

Korman’s helplessness and attempts to maintain composure trigger our own laughter.

The “prisoner” dynamic:

- Korman is a sitting duck. He’s quite literally strapped to a chair.

He’s trapped: between his professional obligation to continue the scene and his human inability to stop laughing.

Genuine humanity emerges.

- For a moment, we’re not watching Harvey Korman The Actor play a dental patient.

We’re watching Harvey Korman, the human being react honestly to something genuinely funny happening to him in real time.

The sketch runs about nine minutes, but Conway’s systematic destruction begins around the three-minute mark and continues through to the end.

Despite Korman’s helplessness threatening to break him, Conway rallies each time, remembering his core objective: a premeditated assault to destroy his scene partner while maintaining his own character’s perfect discipline.

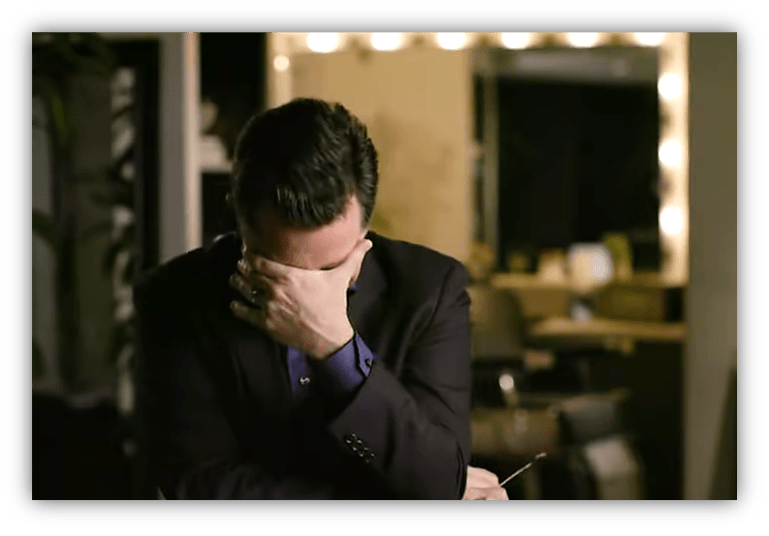

The extent of Korman’s breakdown was legendary.

As Conway later revealed with obvious pride: “As a matter of fact, in the dentist sketch, you can actually see Harvey wet his pants from laughing.”

While I couldn’t find a direct quote from Korman about this particular sketch, it’s virtually certain that his reaction is real. The helpless, uncontrollable laughter that builds and builds is unmistakably genuine.

Conway got what he wanted. And poor Harvey? One thing for sure: He never stood a chance.

As we all know, comedy is subjective. But this kills me. See if you agree:

And If that seems a little “too ‘Carol Burnett’?”

Then I’ll take more ‘Carol Burnett’ any day.

One of the all time greats. I don’t care that it’s broad and over the top, it’s funny. This an the elephant story show that sometime improv is better than scripted comedy. Good stuff!

The elephant story is one of the funniest things that I have ever seen. Every single member of the cast breaks character, including Conway at the end.

For those who haven’t seen it:

https://youtu.be/QUHQkWrqdG4?si=zPJHwoBiCgnFfVgH

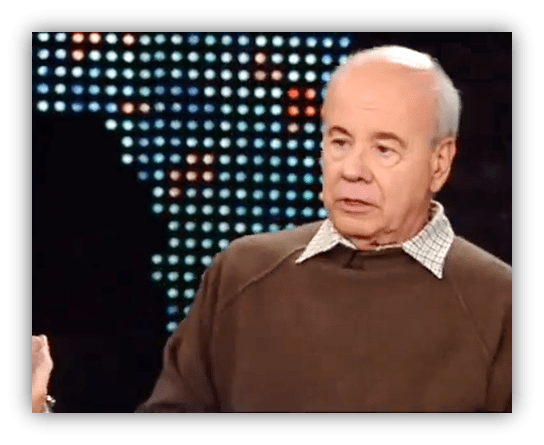

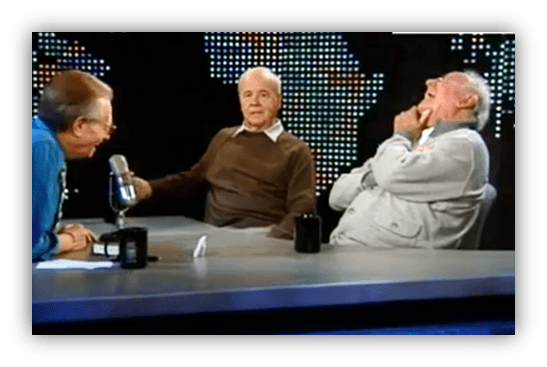

Having written a book about the show, I naturally enjoyed this post even more than usual. Great insights here. I’ll just try to add a few to augment them.

1) Tim started guest starring on The Carol Burnett Show in its first season (1967-68), but he didn’t start doing sketches opposite Harvey until the start of the second season. Their chemistry was immediate, and so the writers would reserve a “Tim bumbles around to the consternation of Harvey” sketch every time he visited.To Carol’s credit, she was willing to let the duo get lots of laughs without injecting herself. Some of the more insecure comedy variety stars like Red Skelton or Danny Kaye would’ve been upset to have been left out and demanded to be included in it to make sure everyone knew who the star of the show was.

2) According to several people I interviewed including Harvey’s son, Harvey never knew what improvisations Tim would spring on him before taping. His crackups were genuine.

3) This bit appeared in the same episode Carol had Ethel Merman as her guest. With the belter in great vocal shape along with other strong element, this is one of the best Carol Burnett Show episodes ever.

4) From what I’ve seen of Saturday Night Live in recent years, Lorne Michaels abandoned his initial edict. The skits–sorry, SKETCHES–have become broad, formulaically corny and filled with actors breaking each other up. In fact, it’s become more like The Carol Burnett Show than its original roots. (And, I should add, there’s nothing with that. After all, the show won 25 Emmys, ranking it 13th all time among all nighttime entertainment shows during its 11-season run . Apparently a lot of people inside and outside the TV industry like their comedy broad, formulaically corny and filled with actors breaking each other up. Nothing wrong with that.)

I have only one gentle criticism about your comment :

You didn’t plug your own EXCELLENT book!

The Carol Burnett Show Companion

https://a.co/d/1Qktlpx

Thank you!

Coming to this cold, it was a slow burner but once Korman breaks down its comedy gold. Korman is both a prop and part of the audience. He’s essentially an inanimate object from the point the first injection goes wrong. There to be used to service the madness of Conway and to provide an up close reaction that in turn encourages the real audience to greater laughter.

I remember seeing this and many other bumbling old man skits with those two and loving all of them as a kid. They don’t crack me up quite the same now to be honest, but hardly anything from that era does. That doesn’t mean it wasn’t genius at the time.

Probably because the internet algorithms know what to serve me, but I have seen this skit floating around the internet dozens of times over the years, but it is so funny. Comedy like this goes over so well when it’s obvious the cast are good friends having fun together…not unlike watching the regulars on Who’s Line Is It Anyway? You feel like you’re virtually in on the friendship.