How a family pastime, a Vietnam radio operator, and a dash of German design culture produced one of the greatest board games of all time

You’ve heard of gateway drugs:

They’re the softer ones with little chance of dependence or injury.

But – they can lead people to stronger drugs, addiction, overdoses, and death. They open the gate to worse effects.

The word “gateway” can be used in other instances, too. I had never heard of ‘gateway games’ until recently.

But there’s a category of board and video games that might enthrall people into taking up gaming as a serious hobby.

They’re designed to be easy for gaming newbies but still deep enough to engage experienced players. The three that are usually mentioned when talking about gateway games are:

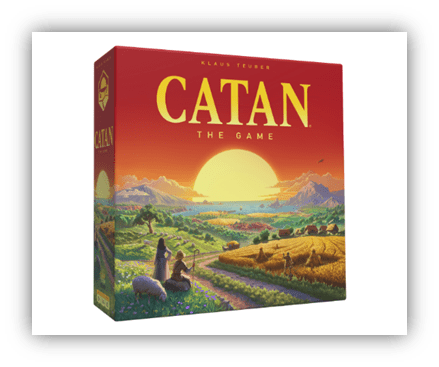

Catan,

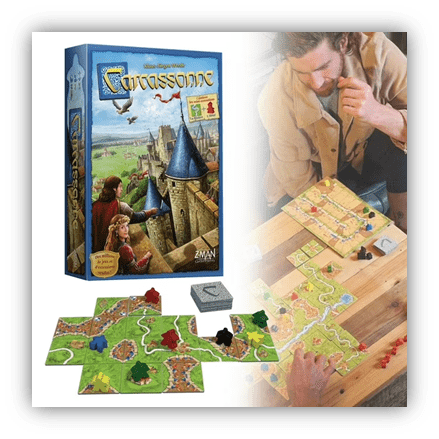

Carcassone,

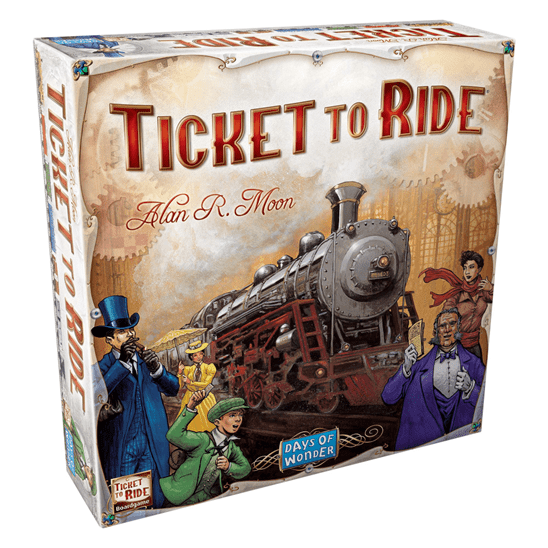

…and Ticket To Ride.

My son loves board games, and he always brings some when he visits.

During the pandemic, my wife and I bought our own copies and played almost every night. We still play several times a week.

We’re hooked.

I guess that makes our son a pusher.

We never moved on to the hard stuff, preferring to dabble in these gateway games. Ticket To Ride is our favorite. We have several different versions of it.

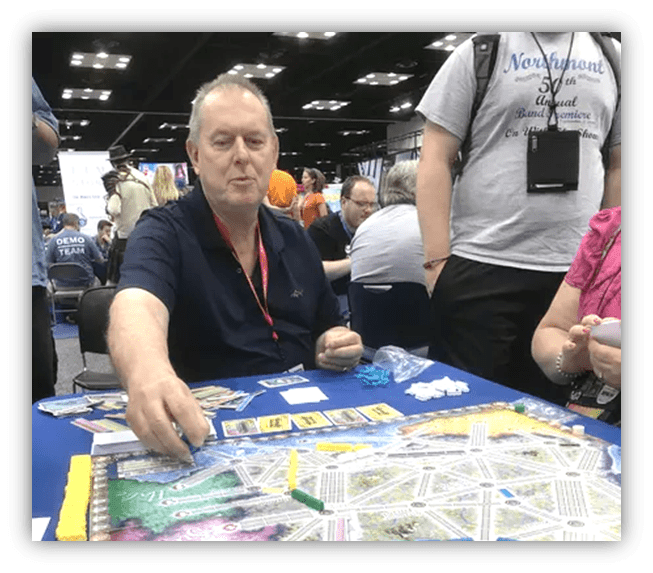

Ticket To Ride was created by Alan R. Moon.

Born in his grandmother’s house in Southampton, England in 1951, his family moved to the United States when he was still a child. He grew up in New York and New Jersey.

For the Moons, Sunday was family day. If they didn’t go bowling or play miniature golf, they were home playing games.

Their favorites included classic board games like Monopoly, card games like Hearts, and — when he got older — chess.

After completing high school in 1970, Moon joined the U.S. Air Force.

He was a radio operator in Vietnam and was then stationed in Nebraska and New Jersey. Following his four year stint, he went to Kean College of New Jersey majoring in English and Theatre, which sharpened his appreciation for storytelling, structure, and presentation.

While there, he wrote articles about games for The General, the house magazine of the Avalon Hill Game Company.

After graduation, Avalon Hill — one of the most influential strategy game publishers in the U.S. — hired him full time. He worked as an editor and developer, refining rules, designs, and continuity. While there, he went through hundreds of games submitted by amateurs, and refined several for publication. It was a crash course in game design, and he learned what made games engaging.

Moon realized he wanted to create games himself.

His first was Black Spy, released in 1981.

It’s a trick-taking card game and was put out by Avalon Hill.

It wasn’t a blockbuster, but it proved Moon’s ability to update traditional formats.

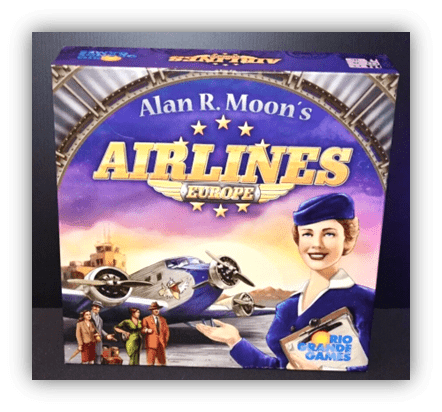

Airlines, published by Abacusspiele in 1990, introduced airline route-building and shareholder mechanics. His reputation grew in European gaming circles, particularly in Germany.

The game’s success hinted at Moon’s knack for creating map-based, travel-inspired puzzles.

Moon founded his own company, White Wind Games, in 1990.

For nearly a decade, he self-published and built a devoted fan base, despite White Wind’s small scale.

“My plan,” he wrote, “was to produce limited editions of my games and then sell them to the big companies a year or two later.”

He waited tables and did other part time jobs to keep the money flowing.

Not a single company bought any of his games.

Desperate, he closed his company and became Director Of Game Development at F.X. Schmid USA. Only then did a company approach him about one of his White Wind games.

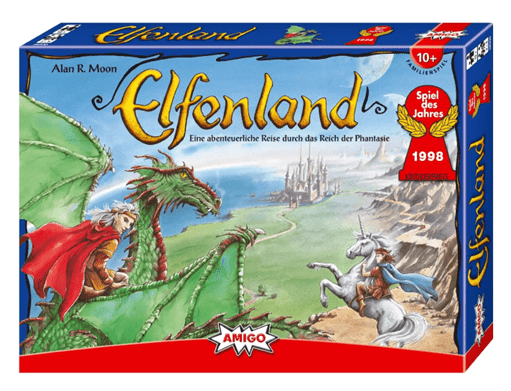

In 1998, Amigo Spiele asked Moon about simplifying his Elfenroads fantasy travel game where players plan routes across a mythical land.

Renamed Elfenland, it won the prestigious Spiel des Jahres (German Game of the Year) prize.

It was a breakthrough, raising his profile internationally as a designer with an eye for accessibility and elegance.

In 2001, three of his games — Das Amulett, Capitol, and San Marco — were nominated for the Spiel des Jahres. None won, but Moon was recognized as one of the great contemporary game designers.

However, the defining moment of Moon’s career came in 2004 when he released Ticket To Ride with a company called Days of Wonder.

While Amigo Spiele specializes in mass-market, compact games that are affordable and easy to distribute, Days Of Wonder is known for high production value and bestsellers.

They don’t publish many games per year, but when they do, it’s a big release, like the latest Star Wars movie.

For Moon, it was like a musician going from self-releases to an indie label and then to a major.

Ticket To Ride’s combination of simple rules, the tension of completing goals, and beautiful high-quality components made it an instant hit.

Like Elfenland, it won the Spiel des Jahres.

But it also won:

- The Origins Award in the USA for Best Board Game

- le Jeux sur un plateau Gold Award in France

- The Årets Spel for Best Family Game in Sweden, and at least a dozen others.

So, how is it played?

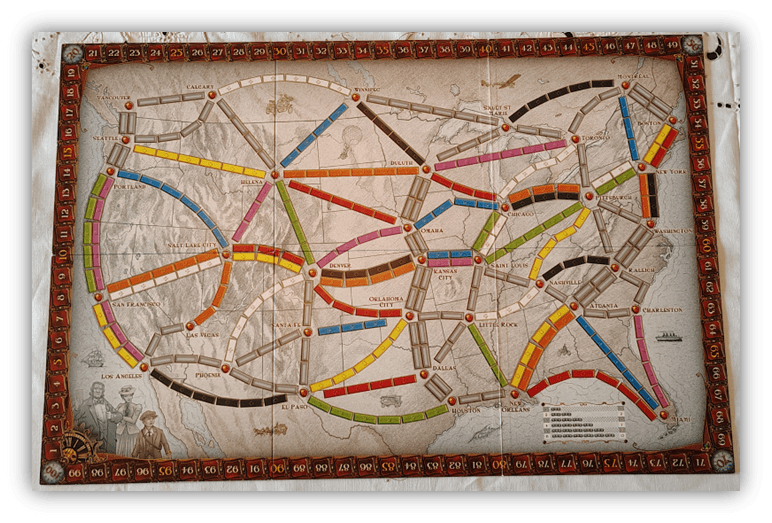

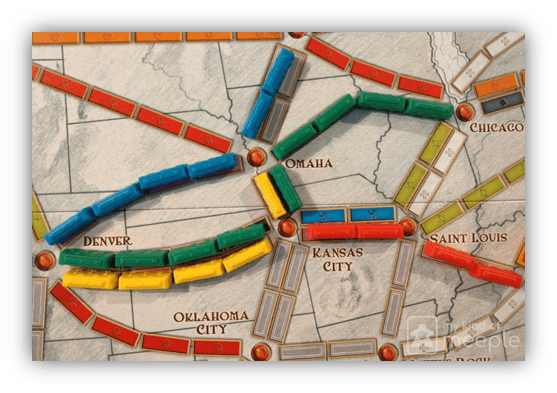

The board is a map of the continental United States and southern Canada.

Cities are connected by routes, some are gray and the rest are in one of eight colors.

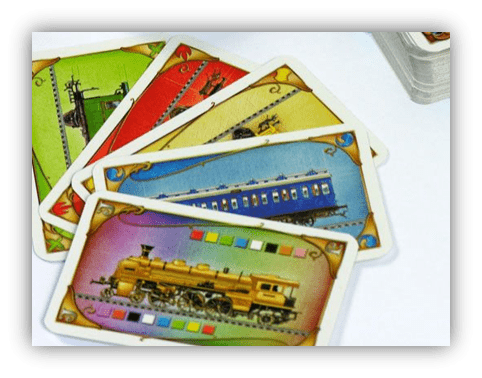

There are two decks of cards. One is of various colors matching the route colors.

There are wildcards, too.

The other contains “tickets” that connect two cities. Each ticket is worth a certain number of points.

Montreal to Dallas, for instance, is worth 13.

The idea is to fulfill the tickets by placing your trains along the tracks to complete the route between the two cities.

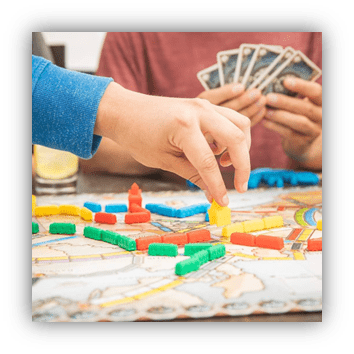

Each player starts with 45 plastic trains of a single color, three tickets (optionally, one can be discarded), and four of the color cards. Only you know which cities you’re trying to connect.

On each turn, a player can pick up more tickets or color cards. When you have enough cards of the same color to connect two cities, you discard the cards, put trains on the route, and move your play piece the designated number of spaces.

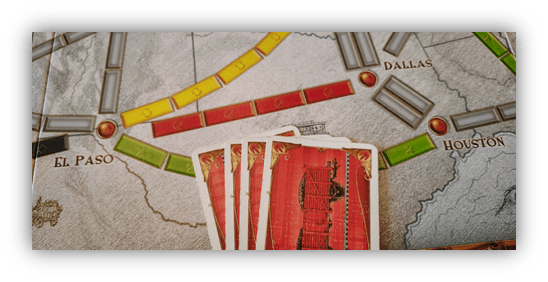

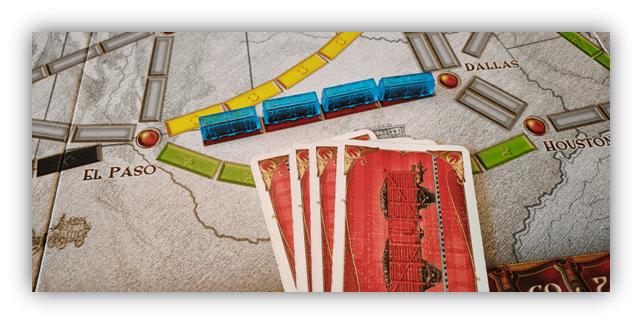

For instance, it takes four red cards to connect El Paso to Dallas.

If you need to get from, say Los Angeles to Atlanta, you could go through El Paso and Dallas. You’d discard your four red cards and put your train pieces on the route to claim it.

Now that it’s yours, no one else can use it.

Gray routes can be filled in with any color cards, as long as they’re the same color.

At first, Ticket to Ride feels calm.

You quietly draw cards, collect the colors you need, and keep your destination tickets in mind.

No one knows each other’s destinations, so everyone’s focused on their own plans, mapping paths in their heads.

But soon, some tension creeps in.

You start to notice another player hoarding red cards, and you desperately need that red route from El Paso to Dallas.

- Do you wait another turn to draw?

- Or do you play what you’ve got before it’s too late?

Every decision has weight because the routes are limited, and you need to get from point A to point B.

Then comes the thrill or heartbreak of a blocked route.

If an opponent puts their trains on a route between cities, it’s theirs and no one else can use it.

Maybe you were one turn away from connecting Denver to Chicago, but another player puts their trains right in your path.

Suddenly your carefully planned path collapses, and you have to reroute through Duluth or St. Louis. It’s frustrating, but it’s also engrossing, because now the puzzle changes.

The pace accelerates and the final stretch is a mad dash.

The long routes out west bring big points, and the players hoard cards and take risks. Someone announces the endgame by dropping their last trains, and suddenly everyone’s scrambling to complete unfinished tickets.

If you don’t complete a ticket, you lose the points it’s worth.

Scoring is always a mix of triumph and tension.

- Players tally destination tickets one by one, with relief for completed routes and groans for unfinished ones.

- Whoever has the longest path gets a ten point bonus, and that often determines the winner, creating a suspenseful reveal at the very end.

The game feels like a cross between a road trip and a chess match — part planning, part improvisation, part luck of the draw. It’s light enough for families, but sharp enough for dedicated gamers.

Ticket To Ride has sold over 18 million copies worldwide, and that’s just the original version.

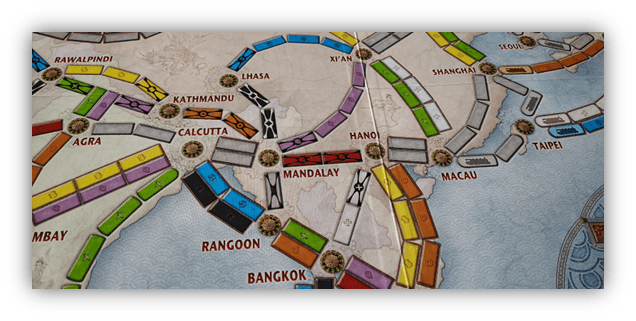

It was followed by Ticket To Ride: Europe which has slightly different rules and won multiple awards. There are also versions featuring Asia, Japan, Poland, and more. Some of these are expansion kits that contain only a new map and tickets, and you would use the color cards and trains from your full version.

It’s a franchise.

Ticket To Ride is considered one of the greatest gateway games ever created — easy to learn, quick to play, and both fun and immersive. Reviews talk about how it strikes just the right balance of simplicity and complexity. It’s used in classrooms to help teach geography, planning, decision-making, and critical thinking.

Alan R. Moon’s reputation was made with his ability to design games that are fun, accessible and challenging, familiar yet innovative.

His fascination with travel and route-building gave the gaming world some of its most enduring titles.

With two Spiel des Jahres awards and a career spanning over four decades, Moon remains one of the defining figures of modern board games.

As for me, I can quit any time I want.

But I need two more blues to get from Portland to Salt Lake City...

Elfenland is such a dumbing down of Elfenroads that I find it depressing. Airlines is an underrated gem. He also designed Union Pacific, which I prefer to Ticket To Ride as train games go.

I like some of these games ok. In our family about half the members devour these types of games, and also dabble in D&D. For me, the more complicated the rules, the less I want to play it. That being said, I’m ok with the occasional game of Catan or House of Betrayal. I’ll bet I would like this game, since it’s geographically oriented, and I like stuff like that. There’s another one that my family thinks that I’d like that is all based around agriculture, but I can’t remember the name of it. So, I am mildly intrigued by your description of Ticket to Ride. Maybe I’ll get them to play it someday (though I don’t know that anyone owns that one).

Agricola? Great game!

Yep…I’m pretty sure that’s it. 🙂

I doubt that I’d get my family to play but the mix of maps, trains and gameplay strategy sounds right up my street. Plus its named after a Beatles song. Whether that’s intentional or not.

We’ve had a few board game phases but Monopoly is the one that always endures. Classic or we have Monopoly Cheat which is quicker and encourages more chaos. We’ve stayed in quite a few holiday lets over the years which often have a supply of board games. The cottage we stayed in at Easter had Trivial Pursuit – but from the early 90s. Which did put 13 year old daughter at a massive disadvantage but she took losing well.

Great read Bill!

(I’ve managed to get signed in again, hi mt58 et al!!)

A few years ago I met Keith Law at a minor league baseball game – he used to be on ESPN but now contributes to The Athletic… and writes board game reviews for Paste(?)

He also keeps his own website, and ranked his top 100 games of all-time. I reached to him and asked what game i should start with when my daughter was 6. He said Ticket to Ride: First Journey.

Since then, we’ve bought 2 more in the series, and have begun to collect many in his Top 10: Carcassone, 7 Wonders, Pandemic, Cataan. These games are so much better than the total luck ones we grew up with!

Thanks for giving this game the love it deserves!

I haven’t played 7 Wonders but those others are all fun. I especially like Carcassone, and now Carcassone (the city) is one of my travel destinations. I don’t know when we’ll get there but that castle looks to be something special.

Whoah. Name-checking Keith Law. He wasn’t a Grantland staff writer but I kind of recall him being an occasional contributor.

Baseball is so unpopular in my neck of the woods, my daily’s website doesn’t cover Guardians baseball even though there is an UH alumnus and a local product on the current roster. Cade Smith was nearly unhittable last season. It’s not his fault that the manager overused him in the postseason. That’s the UH-Manoa product. Joey Cantillo was born here. He currently has a strikeout ratio-per-nine innings of 12.7. And now, here is the slightly more relevant part of the post. Aaron Davenport pitches for AAA Columbus. He is also a UH-Manoa product. Cleveland, potentially, can have three guys with island ties this season. I love Devo and Greg Dulli. It’s not hard for me to root for Ohio.

Risk, forever.