If you play guitar:

Even a little…

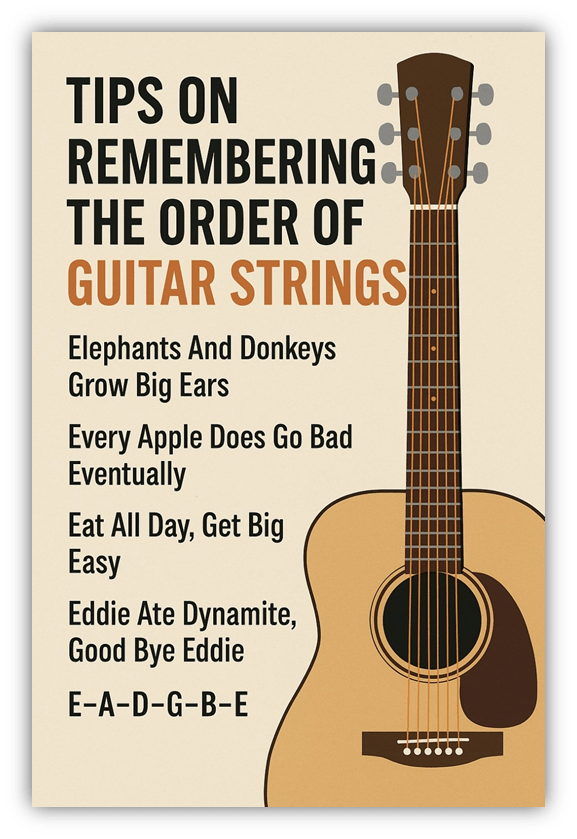

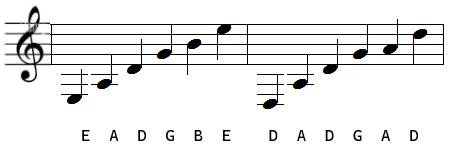

You know that the strings are tuned to these notes, from lowest to highest:

E, A, D, G, B, E.

This is called standard tuning.

Which implies that there are other ways to tune your strings. Some songs are easier to play if you lower the low E string to a D.

Heavy Metal bands, especially Doom Metal and Death Metal bands, will even lower all the strings down a whole step or more to make it sound dark and guttural.

Alternate tunings are nothing new, and some are more used than others.

Many Blues guitarists use this tuning: D, A, D, G, A, D. It even has a name, and it’s pronounced just like that:

“DADGAD.”

John Martyn, the late British musician, was known for using alternate tunings. His official website even lists all his songs and what tunings they use. Many use DADGAD.

So: Let’s say you were a teenager in the late 1970s who really liked John Martyn tunes. You began experimenting with the DADGAD tuning.

But one day instead of tuning the fourth string to a G, you accidentally tuned it to an A. You ended up with D, A, D, A, A, D. That’s three D’s and three A’s. You called it “DAD-Odd” tuning.

The three D’s are an octave apart from each other.

But the two A’s next to each other in the middle are at the same pitch.

This gave your guitar a drone sound, and you decided you liked it. You had to invent new fingerings, but the sound was hypnotic. You wrote a song in this tuning and played it for hours on end.

You always liked that song and showed it to the New Wave band you started years later, but your bandmates didn’t like it.

One guy in particular, the bass player, flat out refused to do it, saying it was “old wave.”

Your band has major label success, and it was time to record your third album in 1982, but you were a few songs short. The record label said you had to come up with something, and you suggested your song again. The bass player still rejected the idea. But he doesn’t have any new material like he usually does.

You and the drummer recorded a demo, the label loved it and said, “it’s going to be on the album.” The rest of the band, even the bass player, acquiesced.

And it was a hit.

Then one morning, one of your musical heroes called you. You told the story years later.

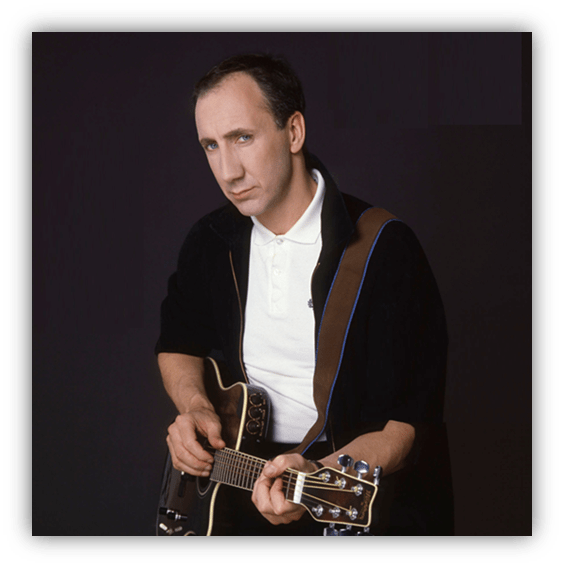

“I got a phone call at 11 in the morning, and somebody gave me the phone and said, ‘It’s Pete Townshend for you.’

And I said, ‘Of course it is, he phones about this time every Saturday doesn’t he?’ I thought it was somebody making a joke.

I picked up very sarcastically, ‘Oh, hello Pete.’ And he said, ‘Oh, hello Dave, this is Peter Townshend here and I’m sitting with David Gilmour, and we’re trying to work out your song ‘Save It For Later,’ but we can’t work out the tuning.’”

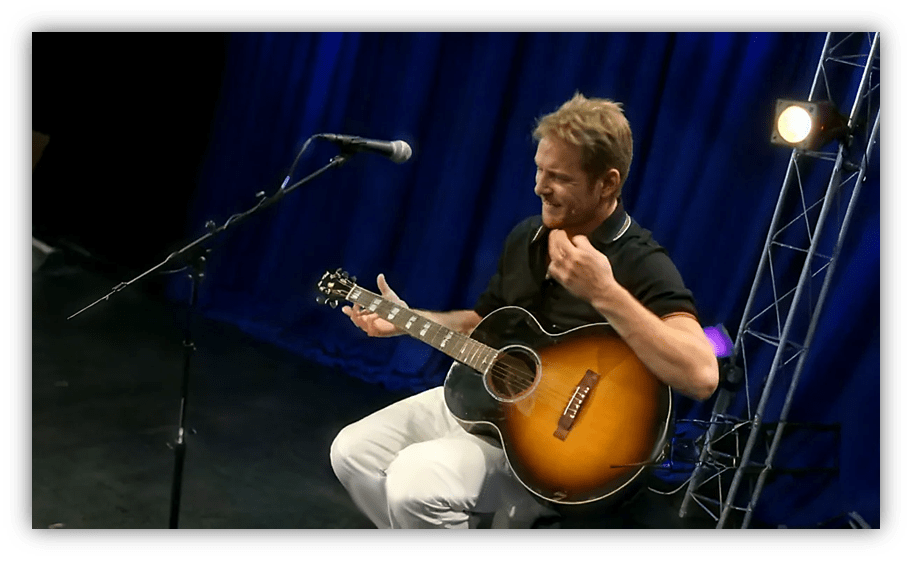

Shocked that he was actually talking to Pete Townshend, Dave Wakeling explained the accidental DADAAD tuning.

“Oh, thank heavens for that!” Townshend said.

“We’ve been breaking our fingers trying to get our hands around these chords.”

“Save It For Later” is about not knowing how to grow up, that feeling of uncertainty entering the world as an adult for the first time.

It makes sense that a teenager would write about the transition from boyhood to manhood and learning how to relate to girls becoming women.

There are some schoolboy jokes in it, too. The title is an intentional homonym phrase for “save it, fellator” and there’s a long pause in the line “just hold my hand while I come… to a decision on it.” It’s stuff that would make a teenage boy giggle.

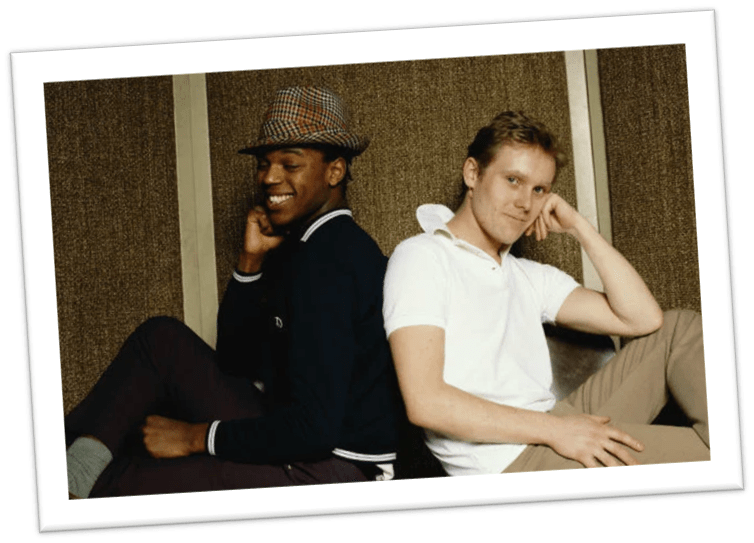

I mentioned Wakeling’s band in my article about Brigitte Bond, The Beat Girl.

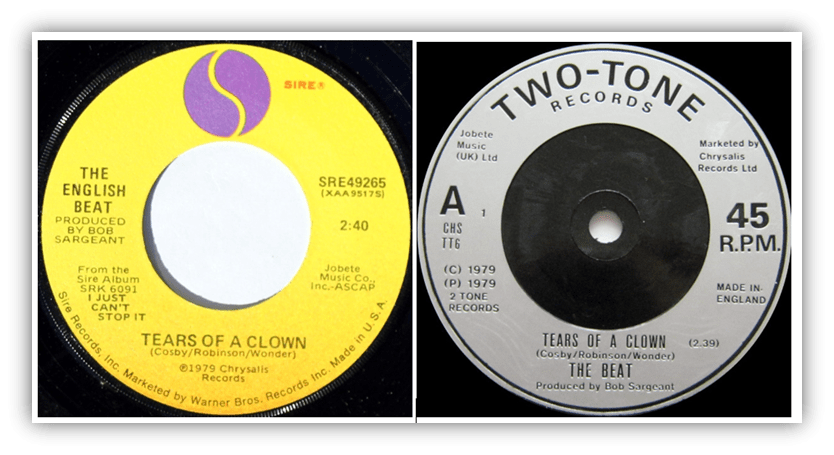

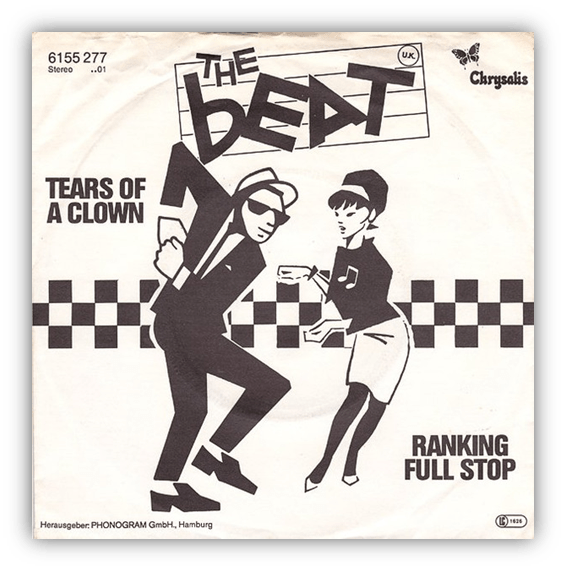

They were called The Beat, but in North America they were The English Beat.

This was to avoid confusion with a band from Los Angeles called The Beat (who later changed their name to Paul Collins’ Beat to avoid confusion with the more popular band from England).

When The Beat started out, the members didn’t have a lot in common musically.

It took them a while to figure out how to combine Wakeling and guitarist Andy Cox’s power-pop melodies with David Steele’s punk basslines and Everett Morton’s reggae drums.

The song that they gelled on was a cover of Smokey Robinson & The Miracles’ “Tears Of A Clown.”

They picked that song because it was the only one that they had all heard before.

Audiences loved it. Wakeling later said,

“…sometimes the punk songs went down great and the reggae didn’t; sometimes the reggae songs went great and the punk ones didn’t.

“But every single night, ‘Tears Of A Clown’ took the roof off the place.”

It was their first single, reaching #6 on the UK Singles chart. They put out 14 singles in all, though “Mirror In The Bathroom” was released twice, once in 1980 and again in 1995 as a remix. All 14 singles charted.

“Save It for Later” was the first single from their third album. Released on April 1, 1982, it was their first song to do well in the States.

Their third album was also their last. The differences of opinion over “Save It For Later” may have contributed to the band’s end, but the larger issue was the question of whether to take a break after years of touring. Steele, Cox, Morton, and saxophonist Saxa all wanted time off.

Wakeling and singer Ranking Roger had young families to support and couldn’t afford a holiday.

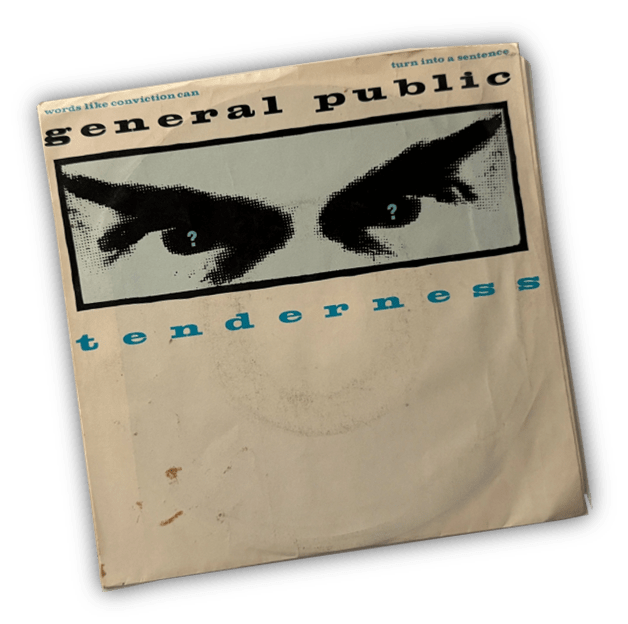

Plus, they liked playing together and Wakeling had written a song called “Tenderness.”

Virgin Records wanted to release it but the other members were dragging their feet about signing a new contract. Virgin asked Wakeling and Roger if they’d release the song under another band name.

“And I said yes,” Wakeling told the AV Club in 2012. “Sadly, that went down in history as me having split the group up, but to be honest, the group had been split up months before then. I was just the one with the balls to pull the plug.”

“And so ‘Tenderness’ became the beginning of General Public’s career.”

“Tenderness” was a hit and General Public had continued success.

After taking their time off, Steele and Cox later formed Fine Young Cannibals with singer Roland Gift.

They were successful, too, hitting #1 in the States with “She Drives Me Crazy” and “Good Thing.”

In 1986, Townshend started performing “Save It For Later” in his solo shows. In this version, he mentions the tuning.

He invited Wakeling to one of his shows and they talked backstage beforehand.

When Wakeling went to find his seat, he found the ticket Townshend had arranged for him was for the front row.

‘I just want you to know that a guy I really admire and a great friend of mine is in the audience tonight, Dave Wakeling, written one of my favorite songs in my whole life and we’d like to start the set with it if you don’t mind.’

“And they played ‘Save It For Later,’ and the crowd all stood up, and I stood up. And I swear I didn’t cry. I didn’t cry, but there were tears rolling down my face. There was no effort to it at all. They were just rolling, rolling. I was mesmerized really for the next hour or so. I couldn’t breathe properly.”

“Save It For Later” only got to #47 on the UK Singles chart and didn’t break into the Hot 100 in the US.

But due to placement in movies and cover versions by Townshend, Harvey Danger, Matthew Sweet & Susanna Hoffs, and others, it accounts for a third of all The Beat’s catalog income. It’s become a classic.

In the end, Steele was right about “Save It For Later.” If aging rock stars like Townshend and Gilmore like it, it’s probably “old wave.”

I am familiar with “Mirror in the Bathroom” (a great song!) and their cover of “Tears of a Clown”. I have, however, never heard “Save It For Later”. The DADAAD tuning definitely makes a difference, making the guitar chords more harmonically ambiguous. It totally works for the song. And it doesn’t sound “old wave” at all to me.