This is the unlikely story of a subculture that emerged in 1970s North of England venerating US soul music:

Northern Soul.

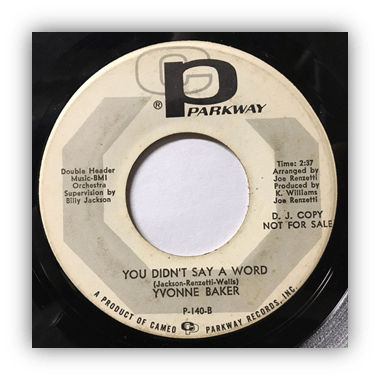

Specifically: obscurities from the preceding decade that made little impact when first released.

Northern Soul isn’t a genre as such, its a movement that collected up records which would retrospectively be given that classification.

Its roots were in the Mod scene that embraced the new soul sounds of Motown. As Mod fragmented, psychedelia usurped it in London and the south.

In working class towns and cities in the North, there was less of an appetite to turn on, tune in and drop out. Psychedelia offered nothing they could connect to.

An underground movement kept the faith and went deeper into soul.

The typical Northern Soul adherents were young adults, working in factories or other repetitive jobs seeking a release from mundanity. The likes of James Brown and Sly & The Family Stone slowed things down and made soul funkier and grittier with a social message.

Northern Soul rejected this.

The working week was hard enough. They wanted to escape.

It gave followers a sense of belonging. A community unseen by the mainstream that allowed a feeling of superiority that was missing elsewhere in their lives.

The early homes of what would become Northern Soul were The Twisted Wheel in Manchester, and Catacombs in Wolverhampton.

As their popularity grew the tempo of what the crowd wanted to hear got faster. They wanted ‘stompers’.

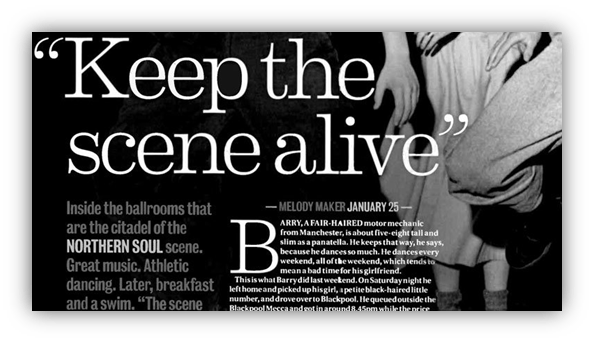

A 1975 Melody Maker article summed up the sound:

“A relentlessly fast snare drum snapping four to the bar; a booming bassline; sharp, toppy brass and/or strings, the vocals varying from intense expressive wailing to mechanical screeching, yet all compelling and involving.”

Its popularity saw its influence reach London. There weren’t many places to find this music but one was Soul City in the capital.

As a journalist, label boss and owner of Soul City, Dave Godin played a huge role in bringing US soul to Britain.

Noticing a steady flow of customers from the north to his store, all asking for the stompers they were hearing in the clubs he came up with ‘Northern Soul’ to describe it.

He had already long been signing off his magazine columns with the exhortation: Keep The Faith – right on now!’

Shortened to ‘Keep The Faith’, it would be adopted as the Northern Soul motto.

The Twisted Wheel was forced to close by local authorities in 1971 due to concerns about drug use. But the movement had enough of a foothold to spread out to even more provincial towns.

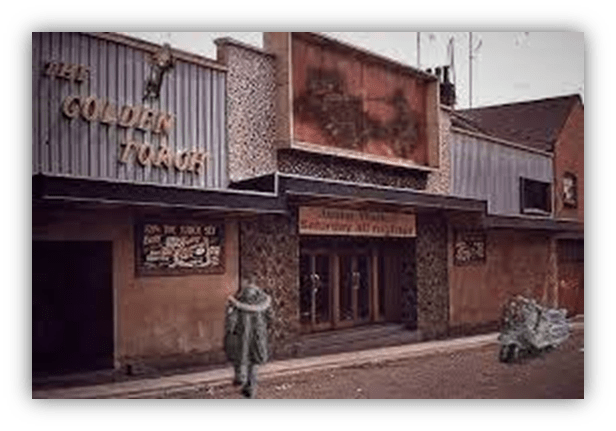

The Golden Torch was the next standard bearer:

An unlikely venue in an unlikely location on a residential street in Tunstall, a small town 35 miles south of Manchester.

Previously a church, a roller rink and a cinema it became a nightclub in the mid 60s.

Its success was its undoing. It had a 500 person capacity, but at its height 1,300 are claimed to have attended.

Then there were the drugs. Amphetamines were an integral part of the experience. Many of the venues that became home to Northern Soul were subject to licensing restrictions on the sale of alcohol.

Which wasn’t a problem, as speed, black bombers, dexys and purple hearts were far more conducive to making it through the all night sessions.

Which in turn perpetuated the trend for faster songs for the amped up dancers.

The Torch went the same way as The Twisted Wheel, 18 months after hosting its first all nighter, the local council refused their license renewal. At which point two more venues took up the story, taking it further north:

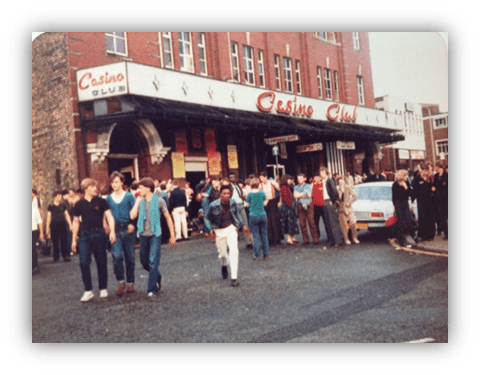

These were the Blackpool Mecca and Wigan Casino.

Blackpool had long been a popular seaside resort so made sense as a beacon for pleasure seekers.

The terms of its license meant that it operated through to 2AM, while also hosting occasional all day sessions running from midday.

Whereas Wigan was best known for Rugby League, and as the subject of George Orwell’s 1937 book, The Road To Wigan Pier, chronicling the deprivation in the town and across industrial Lancashire and Yorkshire.

Another unlikely staging post.

What Wigan did have was the grand sounding Empress Ballroom which by the mid 60s had become The Casino Club. Its large dancefloor made it a much more suitable venue than The Torch, with a 2,000 capacity. In contrast to Blackpool, it stayed open all night. Every Saturday through to 8AM Sunday.

Although Wigan Casino has become known as the spiritual home of Northern Soul, Blackpool was just as important. There was a fierce rivalry for pre-eminence with the two offering different experiences as the decade went on.

Northern Soul was defiantly different. In its championing of failed singles, it was anti-commercial.

Rarity enhanced the appeal and charting singles were generally rejected.

There was obsessive competition between DJs to find records. Exclusivity was prized as a means of attracting the crowds to one venue over another.

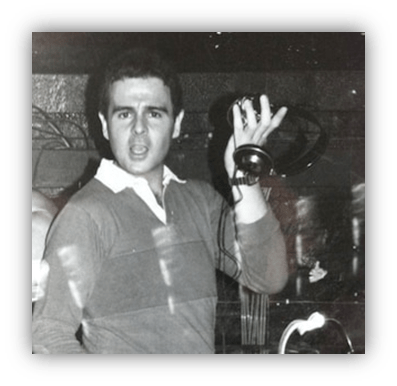

Ian Levine was a resident DJ at the Mecca.

He had an early advantage in coming from an affluent family who took holidays to the US.

In a 2014 BBC documentary he recounted a family holiday to Miami in the early 70s. Rather than enjoying the warmer climes he spent his time scouring record stores, and claimed to have returned home with 4,000 records.

The onset of Freddie Laker’s Skytrain and affordable transatlantic travel meant competing DJs were able to play catch up undertaking their own record reclamation missions.

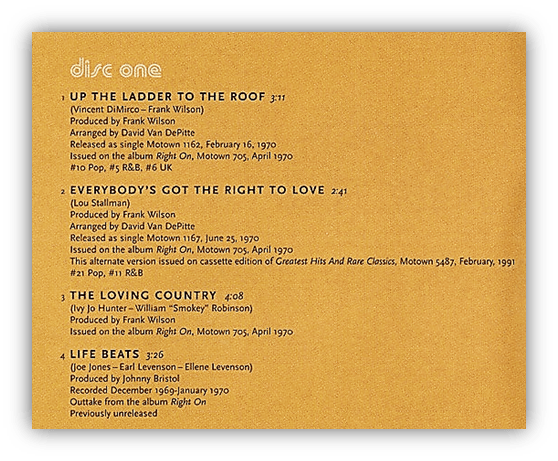

In researching this, a term that has come up in defining the music they were searching for: ‘Failed Motown’.

This is in the sense that Motown inspired numerous small labels and singers to try and imitate their success. The majority of which didn’t come close. This was the fertile ground to source records.

The Supremes definitely weren’t failed Motown. “Life Beats” was due to be the first single after Jean Terrell replaced Diana Ross, but was shelved prior to release…

Making it exactly the sort of rarity Northern Soul craved.

Its not clear how it was found, but obsessive crate digging uncovered it and brought it over to England.

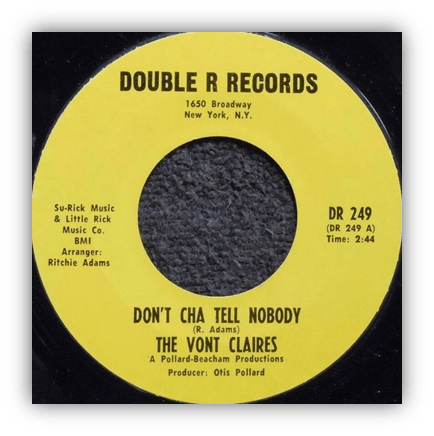

At the other end of the scale are The Vont Claires and Sandi Sheldon.

The Vont Claires entire recorded history amounts to one 1968 single:

“Don’t Cha Tell Nobody,” on the Double R Records label.

A label whose entire output, according to Discogs, amounts to this and one other 7″.

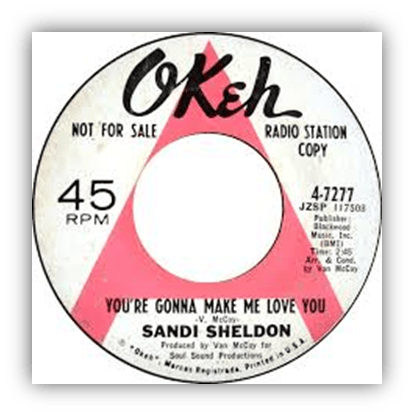

Then there’s Sandi Sheldon. Another whose total recorded output amounted to one single. Kind of.

“You’re Going To Make Me Love You” became a Northern Soul classic.

Such was the paucity of information about these records that it wasn’t discovered until much later that Sandi is really Kendra Spotswood.

Through the early and mid 60s, she worked with Van McCoy, The Shirelles, Dee Dee Warwick and Cissy Houston.

“You’re Going To Make Me Love You” was released by Okeh in 1967 under the Sandi Sheldon alias. A year later she released “Touch My Heart” as The Vonnettes on the Cobblestone label. This too turned up on the Northern Soul circuit – without it being realised there was any connection.

Kendra/Sandi gave up on music after these singles went the way of all her others, making little impact.

When the pieces were put together decades later, Kendra finally got her dues and made numerous visits to Britain to perform at revival nights.

As with any scene, you had to look the part, though this was as much about practicality.

For men:

High waisted Oxford Bag trousers, extra baggy allowing plenty of room for manoeuvre.

Bowling shirts or short sleeved t-shirts and vest tops were essential for keeping cool through the night.

For the women:

High waisted A-line skirts or trousers allowing for flowing movements and again, sleeveless tops.

Attendees would often carry a bowling bag with a change of clothes for once the night was over. These would be accessorised with sew-on badges, enhancing the sense of belonging.

Featuring the raised fist logo, motto and names of venues and chapters.

The practicality of the clothes was necessary, as the dancing was particularly athletic.

Glides and shuffles were standard, switching weight from foot to foot with swift changes of direction. Synchronised handclaps across the whole dancefloor at specific points in songs. For the more advanced there were spins, high kicks, flicks and backdrops. These were exactly as the name suggests, dropping backwards to the floor, landing on your backstretched hands and bouncing back to your feet in time with the beat.

It was all a way of showing off and expressing yourself. Looking at the footage, some of the moves aren’t far away from breakdancing.

For the most part, Northern Soul operated well away from the mainstream.

At its height, Wigan Casino had 100,000 member. So unsurprisingly, the music industry eventually realised there was something going on that they could cash in on through compilations and re-releases.

In 1975, Wigan band Sparkle changed their name to Wigan’s Ovation and released a series of Northern soul covers.

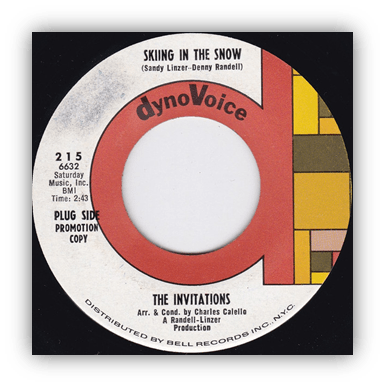

Their version of The Invitations’ “Ski-ing In The Snow” reached #12 followed by another two minor hits.

While in the same year, “Footsee,” a 1968 b-side by obscure Canadians The Chosen Few was remixed with additional sound effects. Their name was amended to the geographically inaccurate Wigan’s Chosen Few and reached #9.

These were derided by scene devotees as cheap, laughable imitations.

In a scene based on setting yourself apart, the increased publicity and popularity was not always welcomed. Reflected in the fact there is very little footage from inside the Wigan Casino.

Most comes from a 1977 TV documentary, but other than this, the mystique was retained with camera access strictly limited.

Into the second half of the 70s, the problem inherent in a scene that relied on uncovering oldies became apparent: They’ll run out eventually.

Blackpool and Wigan adopted different approaches as the flow of records petered out. Led by Ian Levine whose US trips saw him discover the nascent New York disco scene, Blackpool was more progressive, expanding the playlist to include disco, funk and modern soul.

Whereas Wigan remained true to the original ethos. Though the diminishing source of undiscovered oldies meant playing newer records that were a lesser approximation of that sound.

1979 saw the Mecca host its last Northern Soul session. The DJs moved on as new scenes developed, and the crowd aged out without younger devotees to replace them.

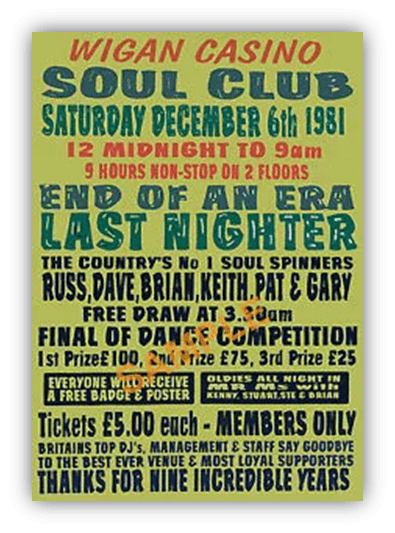

Wigan Casino was forced to close in 1981 when the building was earmarked for redevelopment by the local council.

With the main two venues closed Northern Soul went further into the shadows.

And kept alive in smaller gatherings and a steady stream of compilations. Its had a renaissance in the new century with original followers and new, younger fans.

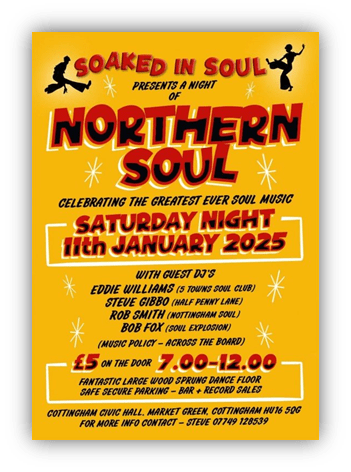

Northern Soul nights happen throughout the country.

There have been books, documentaries, a 2014 feature film titled Northern Soul – and if you look on YouTube you can find a wealth of modern takes on the dance moves.

If you have the money or time to go crate digging and want to get involved, the rarity of some of the songs has made for a lucrative market for original copies. So…

Keep The Faith.

Because that’s where I’ll be heading next time:

With the complicated story of the most expensive of all Northern Soul records…

…to be continued…

Very enjoyable read! So glad you covered this. I don’t remember when I first heard about the Northern Soul movement, but right out of the gate I loved it for its embrace of the obscure. And it is also noteworthy that Soft Cell’s cover of “Tainted Love” would not exist without it.

Back in 2016, I started a Northern Soul playlist on Spotify. It’s a bit smaller than yours, and I don’t remember where or how I found the songs I included. I’d be interested to see what you think of it. We have 3 tracks in common.

https://open.spotify.com/playlist/2Gpmihxh7O9ekl9rHGu50f?si=93e3e681e8f746d7

Thanks rb!

There are some great tracks on your playlist, some I know and others I don’t. The number of records they uncovered runs into the thousands so although there are certain ones that turn up all the time on compliations and best of Northern Soul assessments, there are so many more out there.

I didnt want to overload my playlist so picked out a mix of obvious and not so obvious.

There’s A Ghost In My House was a big song on the scene. Its popularity led to it becoming a #3 UK hit in 1974, seven years after it was recorded. It also shows up an elitist attitude in the scene. Ian Levine discovered it but subsequently described it as “a nasty white pop record on Motown, I suppose I should be ashamed of it”. Northern Soul and commercial success weren’t aligned.

Tainted Love is probably the one that everyone knows due to the Soft Cell version. Marc Almond was a cloakroom attendant at the Warehouse in Leeds which held Northern Soul nights so heard it there. They had a #3 UK hit with ‘What’ another song he’ll have heard there. Originally recorded by Judy Street.

Interesting about the deejay’s about face when the song got popular. Motown had a few white artists. Chris Clark was a 6-foot tall platinum blonde white woman that Barry Gordy signed, even though he said he would never sign a white woman. She never quite caught on here, but was known as the “white negress” in the U.K. She apparently caught on in the Northern Soul scene. “Love Gone Bad” is kind of a banger. She worked at Motown for years afterward. The Mob has the first song on my playlist, and they were a white band out of Chicago. They were not aware at the time what was happening with their music in the U.K. They are not well-known in the U.S., though their inclusion of a horn section pre-dated and may have influenced other more successful Chicago bands that immediately followed, such as The Buckinghams, Ides of March and Chicago.

You’ve twice inadvertently stumbled onto the territory of my follow up piece about one of Northern Soul’s most fabled songs. The song in question is on your playlist – I’m not going to reveal which one so as to leave some mystery. And now the mention of Chris Clark who plays a peripheral role in that story. Based on those details you might know which song it is. I’ll be interested to see when the next part goes live if you already know about it or worked out what it is.

I actually don’t know off the top of my head, but when it’s revealed I will probably be like, “oh, yeah, that song!”

By far the most fascinating thing to me about the Northern Soul phenomenon was the focus and fearless championing of obscurity.

When I was about 10 years old, my mother surprised my brother and I with a batch of brand new 45 RPM records that she’d bought at the local five and dime. It was a shrink-wrapped lot of about 20, without the paper sleeves. Just the vinyl. I’m sure she only paid a dollar or so for the whole bunch.

Each had a little hole drilled though the label. I learned years later that this designated them as “cut-outs;” records that were written off inventory and destined to be sold off in bulk. Of course, we no idea that they were duds. We thought were listening to “big hit records.” It seems to me that the majority were of the Failed Motown soul genre that JJ references.

It’s a delight in 2025 to occasionally run across one of them in the wild, perhaps on an obscure internet radio station or on YouTube. It indeed feels like belonging to an exclusive club of sorts. The members recognize and appreciate songcraft and performances that didn’t have the promotion or luck to become hits, and were destined to slip through the cracks of pop music history.

I get it. Standing up for the underdog, and saying, “Well done. You did a great job on your forgotten record. You should be really proud.”

The Northern Soul Experience. It’s another in a long line of those, “Gee. I wish I coulda been there’s.”

Anyway, here’s Lee Brackett.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=66su_GNDb0I

What happened to the 45s, do you still have them?

There’s currently a copy of I Said Goodbye To Shirley on Ebay for £17 / $22. Would be quite an investment on the $1 your mother paid.

I knew Lee Brackett was obscure by the fact that googling his name brought up a character from the Halloween films and adding ‘singer’ after his name came back with the possibilities of Leif, Lee or Lesley Garrett before any results for Lee Brackett.

That level of obscurity, even in the online age, is exactly what Northern Soul DJs craved.

https://www.ebay.co.uk/itm/391951824960

Sadly, no. A few years ago I had to relocate, and there simply wasn’t anywhere to store my 45s, which had incrementally increased in quantity to about 3000 items.

I had garage sales, eBay postings, and giveaways to worthy homes, and no longer have any of them.

I feel equal parts uncluttered and regretful.

I waffle back and forth frequently over this same dilemma. Sell all my vinyl or not?

I threw out my cassettes in the 00s. Sold my CDs in the 10s. That’s freed up plenty of room. The vinyl is going nowhere.

Correct answer

Don’t, unless it’s to me.

How wonderful. Your mom inadvertently gave you your fist experience falling deep into the near bottom of the music rabbit hole, and a wonderful introduction to being a lifelong music nerd. That is just awesome. If you wanted to talk further about that experience, and what was in that collection, I would read that article.

Hmm…

You know you wanna…

Proof positive that not all great music become hits and by extension vice versa. Great stuff, JJ, I’ll be listening all day (but won’t be doing any backdrops).

Didn’t Tom Briehan mention Northern Soul more than once and say how much he wished he could have experienced it? Or maybe I’m remembering a later British craze?

I’m trying to think when it might have come up. He covered Frankie Valli a number of times, normally that level of success would omit them from Northern Soul consideration but early 70s single The Night was a failure commercially which allowed it entry into the Northern soul scene.

Most likely are Dexys Midnight Runners. They were influenced by the scene, covered a couple of big Northern Soul songs; Breaking Down The Walls Of Heartache and Seven Days Too Long. Plus their first UK #1 was a tribute to Geno Washington.

Indeed it was Dexys, he included this paragraph:

Originally, Dexys was inspired by Northern soul, a UK subculture that I have always found fascinating. Long before raves were a thing, pasty and underemployed British kids would stay up all night dancing frantically to the fastest, most unhinged obscure American R&B records they could find, and a whole subculture, with its own fashion and slang and drugs, came out of it. (Dexys Midnight Runners were named for dextroamphetamine, a type of speed that these kids would take to enable the staying up all night part).

That was me, about 8 comments up ^

Orange Juice’s Texas Fever is my favorite EP ever. I first heard “A Place in My Heart” on an OJ compilation album In a Nutshell. It also contained “Bridge” and “A Sad Lament”.

If I could choose a singing voice, I’d want to sound like Edwyn Collins on the Al Green cover “L.O.V.E. Love”.

I remember reading the review for Texas’ Southside, a no-risk disc, in Pulse. The journalist thought it was a Wim Wenders reference. It could. It could also be a shout-out to the Texas Fever album track “The Day I Went Down to Texas”.

In the CD booklet for the Orange Juice compilation with the painted dolphin man on the coastline, there’s a photo of the hotel welcoming The Sylvers and Orange Juice, in that order, on a small billboard.

I like punk, too. But I don’t come across as your typical punk rock guy. I’d probably fit in better with the Northern Soul crowd.

I played a couple of songs. These guys don’t sound twee.

Twee, I guess, was Edwyn Collins’ contribution to Northern Soul.

I haven’t seen Orange Juice mentioned in connection to Northern Soul before. There’s a definite soul influence in their work but as a band its a case of wrong decade, wrong nationality and not overtly a soul act to qualify.

Al Green is an example of the strictness of qualifying criteria. As Al Green he doesn’t fit the bill but his early career incarnation as Al Greene & The Soulmates do qualify. There’s a song called Don’t Leave Me that crops up on a number of Northern soul compilations.