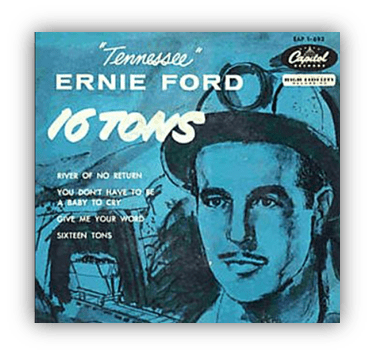

The Hottest Hit On The Planet:

“Sixteen Tons”

by “Tennessee” Ernie Ford

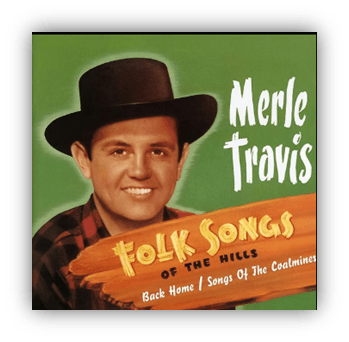

Merle Travis – the original composer and performer of “Sixteen Tons” – came from Muhlenberg County, Kentucky.

It was a major coal mining centre. Decades later it would produce more coal than the rest of the United States combined. The house he grew up in was owned by the Beech Creek Coal Mining Company.

The house had no running water, electricity, or a rug on the floor.

To be fair, this was the 1920s, and most rural homes had no electricity yet, particularly in deepest darkest Kentucky. But the point is, life was tough.

When Merle wrote “Sixteen Tons” in 1946, company stores still existed, predominantly in coal mining towns.

In these towns, the coal mines would be the only employers, the company store the only store:

A situation that allowed the coal company to pay their employees in their own currency, that was only accepted by the company store. Imagine that, being paid in a currency that could only be spent at a store owned by the company paying you.

When Ernie recorded “Sixteen Tons” in 1955, there were still a few around, although they were fading as workers started buying cars and could drive to the nearest town instead.

Also, the whole “being paid in a currency that wasn’t American dollars”‘ “thing was illegal now.

Merle wrote “Sixteen Tons” because Capitol Records wanted him to record a folk album.

A folk album by Burl Ives had just been a big success, and they thought Merle could do the same.

Merle was worried that Burl had already taken all the best folk songs, so Capitol suggested he write his own.

So he just knocked off two songs about his father’s old coal mining days: “Sixteen Tonnes” and “Dark As A Dungeon.”

Burl had sung about hopping freights, Merle sang about digging for coal.

Merle’s version of “Sixteen Tons” was not an immediate success. Merle was having quite a few hits at the time, but this wasn’t one of them. It may have been just a little bit too left-wing for the times.

The Cold War was just beginning, and though McCarthyism was still years away, it wasn’t a good time to get a reputation as a communist.

Legend has it that the FBI got in contact with radio stations and directed them not to play it. Maybe the tobacco lobby was after him as well, since in the very same year, Merle co-wrote “Smoke, Smoke, Smoke (That Cigarette)”. That song was a really big hit. Possibly the biggest country hit of the year.

The more observant of you will have noticed then that Merle was obsessed with Saint Peter. That’s two hit songs with a Saint Peter reference, written in the same year!

The Saint Peter reference in “Sixteen Tons:”

“Saint Peter, don’t you call me, ’cause I can’t go

I owe my soul to the company store”

It had come from something Merle’s coal-mining father used to say. He was probably also worried that they wouldn’t accept the coal company’s currency in Heaven.

Merle’s version of “Sixteen Tons” was so much a non-hit that it appears to have been completely new to everyone when Tennessee Ernie Ford performed it on NBC in 1954, probably during his short stint as presenter of “College of Musical Knowledge”.

A few months later he sang it at the Indiana State Fair to a crowd of 30,000.

They went wild. They sang along. His record hadn’t even been released, yet and everyone seemed to know the words. And when it finally was, it was relegated to the B-side. Nonetheless, it would sell a million copies in 21 days.

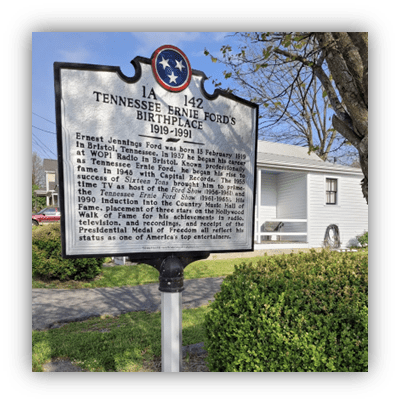

Tennessee Ernie Ford was born, you’ll never guess where?

In the town of Bristol, on the border of Tennessee and Virginia.

And when I say border, the state border literally runs down the middle of the main street: State Street. Or possibly he was born in Fordtown, just up the road, so called because everybody there’s name was Ford. Doesn’t really matter… it was still in Tennessee.

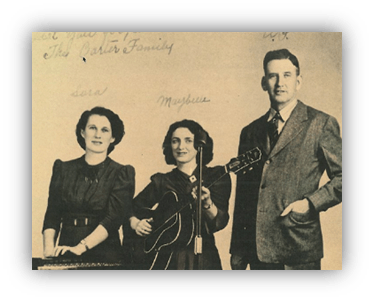

Bristol was known as the birthplace of country music:

Since it was where Ralph Peer from Victor Talking Machine Company, recorded Jimmie Rodgers and The Carter Family back in the 1920s.

If anybody was qualified to make a prime-time variety show version of country music it was Tennessee Ernie Ford from Bristol, Tennessee.

Ernie’s childhood did not involve shoveling lumps of coal.

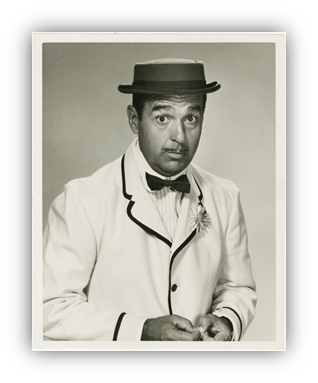

Instead, he dreamt of being on the radio, and due to his freakishly deep voice, it wasn’t long before he did. At some point Ernie ended up in Pasadena, California, where his Tennessee background was a novelty that he could lean into… and lean into it, he did!

Prior to “Sixteen Tons”, Ernie was most famous for his guest appearance on I Love Lucy, playing Lucy’s cousin from Bent Fork, Tennessee (which doesn’t exist). They were really pushing the Tennessee angle weren’t they? But Ernie was truly from there. He didn’t need the quote marks.

The arrangement of “Sixteen Tons” is simplicity itself.

A shuffling jazz beat, occasional appearances by creepy clarinets, and Ernie’s baritone filling up the rest. Ernie sounds both congenial – as a 50s celebrity ought – and vaguely threatening; the product of an upbringing tougher than any of the record buyers watching Ernie on television could possibly imagine.

I mean,

- He was born one morning when the sun didn’t shine

- He picked up a shovel and he walked to the mine

- He loaded sixteen tonnes of Number 9 coal

And the straw boss said “well, bless my soul.” As well he might… have you ever seen a newborn baby pick up a shovel?

Such imagery is surreality itself, if a little overdone. Ernie, we are led to believe, was raised by an old mama lion.

Sure you were Ernie, sure you were.

We are also meant to believe that if we see Ernie comin’, we better step aside. A lot of men didn’t, a lot of men died. This really stretches the bounds of credibility:

Are we really supposed to believe that radio announcer/variety show host – Ernie would get his own variety show the next year, “The Ford Show”

– you’ll never guess who the sponsor was –

…That Ernie would kill someone with his bare hands merely for neglecting to get out of his way?

The over-the-top surrealism of “Sixteen Tons” – and the bare bones, muscle and blood, of the accompaniment – is what makes it magical.

It may also be what saved Ernie from being blacklisted for singing – an argument could be made – the most forceful critique of the owners of the means of production to have made the top of the pop charts. The FBI couldn’t stop it from being a hit this time.

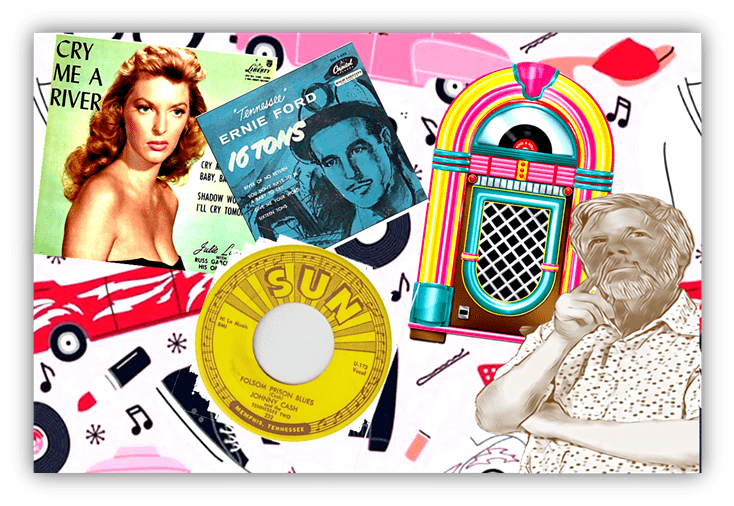

“Sixteen Tons” is a 9.

“Sixteen Tons” has a lot in common with our next song. Both are extremely manly songs, in which the narrator demonstrates how manly he is by bragging about, or at least casually mentioning, that he has killed a man. Or in the case of “Sixteen Tons,” “a lot of men.” And in both songs the narrator is trapped in some sort of bondage… what was going on in the 1950s?

I am of course referring to…

Meanwhile, in Tennessee Land…

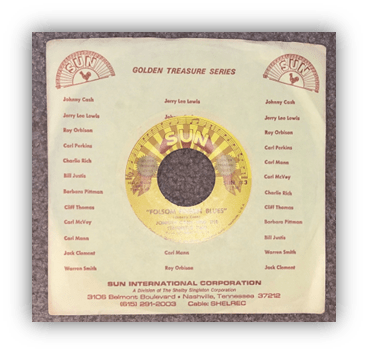

It’s “Folsom Prison Blues”

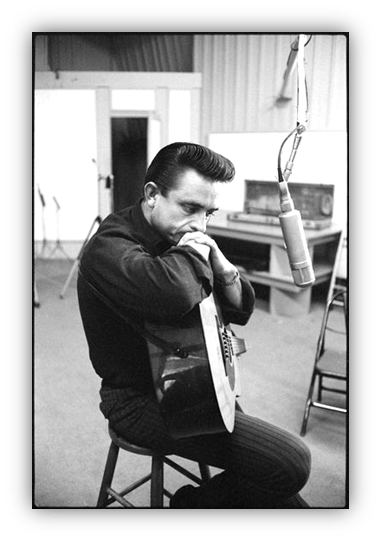

by Johnny Cash

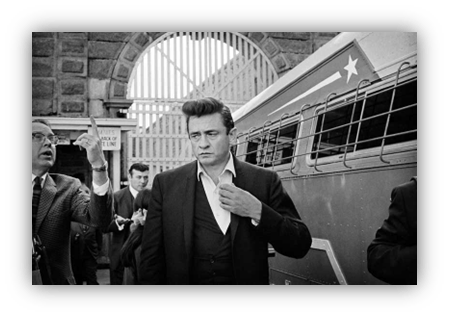

“Go home and sin, then come back with a song I can sell.”

That, or so discredited legend has it, is what Sam Philips, bossman at Sun Records, told Johnny Cash, after he’d played Sam a bunch of gospel songs.

It wasn’t that Sam Philips didn’t like gospel songs. And it wasn’t that Johnny Cash hadn’t sung them well. Sam Philips had released gospel records before. He’d released a lot of whatever style of music the good people of Memphis wanted recording:

The result of his slogan:

“We Record Anything-Anywhere-Anytime.”

He’d even released, and this feels relevant, a gospel band serving multiple prison sentences for rape and murder (at least one of which was innocent) who called themselves The Prisonaires. But we’ll get into their story sometime next year.

Since then, however, Sam had discovered Elvis.

And although Elvis wasn’t quite the King yet – just a hopped-up country singer with a buzz about him – Sam’s ambitions were beginning to grow.

No longer was he recording “Anything-Anywhere-Anytime.” Now he was looking for songs he could sell.

Except that Sam apparently never said such a thing. But with a monumental legend like Johnny Cash, you need your mythical origin stories. Something that might explain where a song like “Folsom Prison Blues” comes from. There are various reasons to doubt the “go home and sin” story, not the least of which is that Johnny Cash had already written the song, a couple of years earlier.

But before we get into that, a little backstory.

Johnny Cash was born J.R. Cash, because being Christened with initials is apparently acceptable behaviour in Arkansas.

The R came as a result of a compromise between his parents who couldn’t decide whether to call him River or Ray. I have no idea where the J came from.

Johnny Cash decided what he wanted to do with his life at an early age, that age being four. He decided that he wanted to be a radio announcer – this is becoming a bit of a reoccurring theme – after listening to a record playing on a Victrola. Perhaps inevitably, it was a railroad song.

Becoming a radio announcer may have seemed like an unrealistic goal as a little boy, at which time Johnny Cash sounded like a little boy;

But then his voice broke, and he began to sound like… well, like Johnny Cash.

He opened his mouth and out came: “Hello, I’m Johnny Cash.” Except nobody was calling him Johnny Cash yet, not even himself. He was still just J.R. Johnny Cash finally agreed to have a regular name when he applied for a job in the Air Force. The Air Force, it appears, does not accept initials as a name.

Johnny Cash spent a few years in the Air Force, stationed in Germany:

Decoding Morse code messages by the Russians, including one in which he was the first American to hear the news of Stalin’s death

(Stalin’s cronies were rumoured to have gathered around his bed in the last hours, just to watch him die.)

Johnny Cash has even attributed the chunk-a-chunk rhythm in so many of his songs – including, presumedly “Folsom Prison Blues” – to the tappy-tappy rhythms of Morse-code.

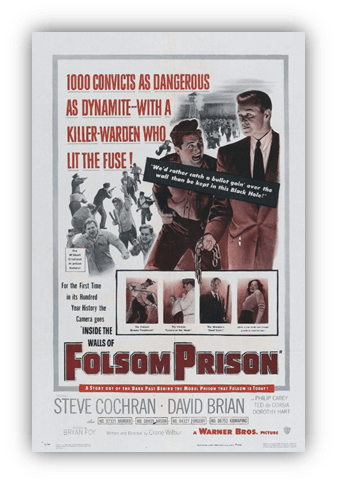

Whilst stationed in Germany, Johnny Cash saw a movie: Inside The Walls Of Folsom Prison.

Johnny Cash saw the movie and he decided that he wanted to write a song about what he thought it was like to be a prisoner in such a prison.

Mind you, when I say “wrote”, I mean that in the loosest way possible.

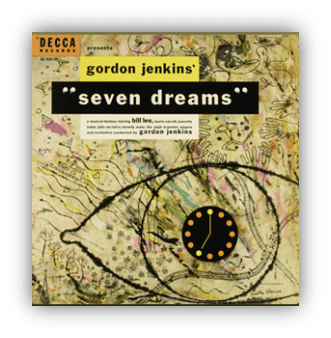

in addition to seeing a movie whilst he was stationed in Germany, Johnny Cash also heard a song: “Crescent City Blues” by hit orchestral conductor, Gordon Jenkins and his wife Beverly Mahr. It may sound familiar.

Gordon Jenkins had conducted for Billie Holiday, and Louis Armstrong, and Marlene Dietrich; none of whom are country.

Probably the closest Gordon had come to country was his turn as conductor on The Weavers records:

The folk group who had a whole bunch of huge hits in the early 1950s before being put on a blacklist for being Communists.

Together, they took a song that Leadbelly liked to sing, placed some very early 50s strings behind it, at sent it racing up the Best Sellers in Store chart to Number One for weeks and weeks and weeks towards the end of 1950.

By 1953 Gordon Jenkins was famous enough that a concept album about dreams could make the Top Ten.

(Not many people were buying full albums yet in 1953, so this is probably far less impressive than it sounds)

Despite being nothing but a telling of seven dreams, including one – the second – in which the narrator is a train conductor.

A lot of random things happen in this dream – a political parody., some bad Irish jokes – before we get to the song, but eventually – about five and a half minutes in – the train stops, the narrator/conductor hops off to have a cigarette, and he “hears a voice in a shack across the way.”

I honestly can’t imagine that this got played on the radio much, but that’s how Johnny Cash heard it in Germany.

And he picked up his guitar, and just fooling around, transformed the song into what he imagined being locked up in a prison might be like. He didn’t have to chance much. Only a few of the lyrics, and pretty much none of the melody.

The most revealing change of lyric between “Crescent City Blues” and “Folsom Prison Blues” is what those rich folks are eating in their fancy dining car… Beverly pictures it as “pheasant breast and Eastern caviar.”

This is so far removed from the experience of Johnny Cash’s character – and probably Johnny Cash himself – that they are reduced to the far more modest and manly “drinking coffee and smoking big cigars.”

Of course there’s also, “I shot a man in Reno, just to watch him die.” Where did that line come from?

Here’s Johnny:

“I sat with my pen in my hand, trying to think up the worst reason a person could have for killing another person, and that’s what came to mind.

And indeed, that is a terrible, and evil reason. It makes Johnny sound like a psychopath. Such a psychopath that his mother felt obliged to tell him “always be a good boy, don’t ever play with guns.” And she told him this… WHEN HE WAS A BABY!!!!

I don’t know about you, but I’m kind of relieved that this guy is in prison.

Imagine if he was still on the streets! It’s a chilling thought.

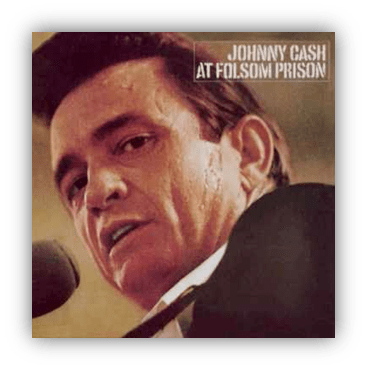

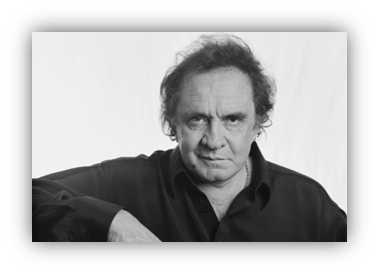

It’s also chilling to hear the versions on “Live At Folsom Prison” and “Live At San Quentin”, the two classic live albums recorded in one of the many prisons in which Johnny Cash liked to play. In which Johnny Cash sings his prison fantasy to literal prisoners. In which Johnny Cash delivers the “Reno” line and the prisoners all whoop and holler and cry out “YEAH!”.

Once again, I can’t help but feel relief that these guys are locked up. They scare me.

So it’s also a bit of a relief then to learn that the prisoners did not actually whoop and holler and cry out “YEAH!!”… that all of that was added during post-production.

The prisoners were actually surprisingly well behaved. No doubt some of them had parole hearings coming up.

Those live albums, it is worth noting, are by far the biggest selling albums Johnny Cash ever put out – not counting all the very many greatest hits compilations – because that’s what happens when your first classic is about a jail:

You become the jail-guy.

Johnny Cash plays “Folsom Prison Blues” with more gusto on those albums than he did on the original record, back in 1955, and so those versions may even be better (despite, or, let’s face it, because of all the murderers cheering him on in the background.)

But the 1955 version already features, full-formed, every component of the Johnny Cash sound

The baritone growl, the patented guitar-twang – not to mention a large chunk of his myth. Not only did it sentence him to a lifetime of performing in jails, but there are people in this world – perhaps the majority, perhaps yourself – who truly believe that Johnny Cash did shoot a man in Reno, just – c’mon everybody, you know the words:

To… watch… him… die.

Hate to destroy your illusions, but Johnny Cash probably didn’t actually kill a man in Reno, just to watch him die, if for no other reason than the fact he lived in Memphis, and Reno, Nevada – let alone Folsom Prison, California – would have simply been too far.

Hate to destroy your illusions even further, but Johnny Cash only spent maybe one, maybe two, nights in jail in his entire life.

For drunk and disorderly behaviour and for sleeping off a hangover.

Still, that’s quite a legacy for one song to have.

“Folsom Prison Blues” is a 10.

Meanwhile, in Sexy Sultry Sirens Land…

It’s “Cry Me A River”

by Julie London

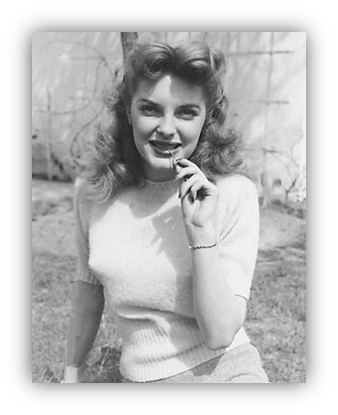

It was the Golden Era of Hollywood bombshells, into whose ranks Julie looked as though she might ascend, but never quite did.

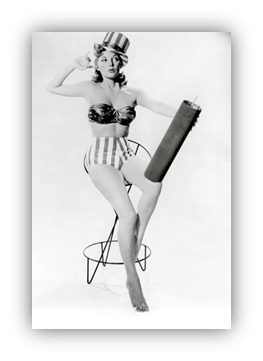

It was the Golden Era of Patriotic Pin-Up Girls:

Of which Julie had positively been one.

It was the era in which Playboy became a cultural force, particularly once Marilyn Monroe turned up on the cover.

It was inevitable perhaps, that one of those Pin-Up Girls, one of those Hollywood bombshells, would become a pop star, and have a pop hit.

Julie London was that pop star, and “Cry Me A River” was that pop hit.

A sultry, smoky supper club pop hit, but a pop hit nonetheless.

As a Hollywood bombshell, Julie had been strictly B-grade.

She wasn’t Marilyn Monroe. She wasn’t Jayne Mansfield. She wasn’t Jane Russell or Lana Turner. She wasn’t Sophia Loren or Kim Novak.

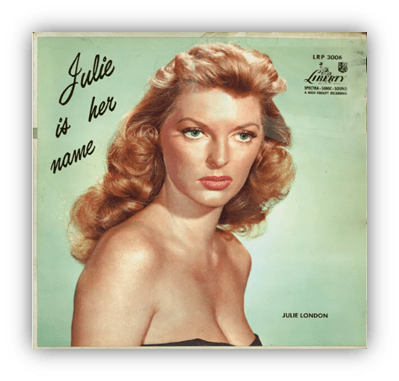

But she looked good on a record cover and that’s what was important.

Even Julie herself seemed to admit that the record covers were more important than the music:

“Just as long as they buy the records, I don’t care why they buy ’em.

We spent more time on the covers than the music.”

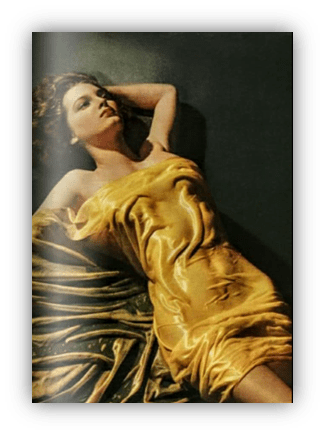

So she released albums such as this one…

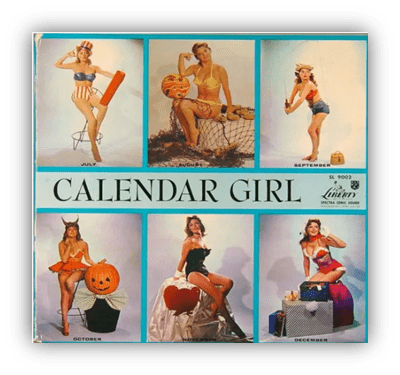

And this one…

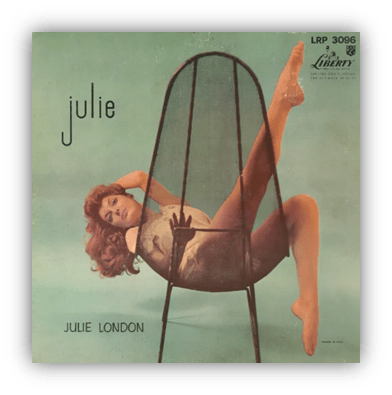

And this one…

Julie London had always been in “the business.”

Her parents had been vaudeville performers. They weren’t famous exactly – they don’t have a Wikipedia page – but they did have a radio program. Julie sang on it when she was four.

And that was that for over a decade.

Until she was discovered by talent agent and former-flapper phenom Sue Carol:

Whilst working as an elevator operator on Hollywood Boulevard – a handy place to work if you want to be discovered – at the age of 17.

Wikipedia claims that Sue was “struck by London’s physical features.” Indeed.

Pretty much instantly they gave her a photo spread in Esquire.

And just as instantly she starred in whatever this is…

Julie’s movie career never really got much better than Nabonga.

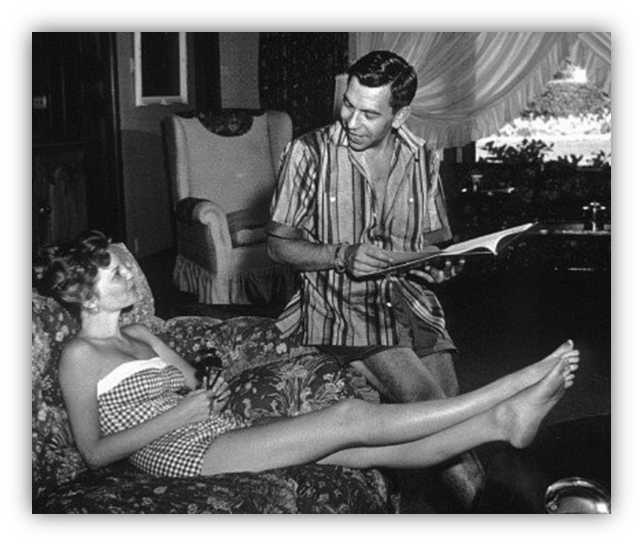

By the time she recorded “Cry Me A River” she was probably more famous for who she had been married to, and then divorced from: Jack Webb, star and creator of “Dragnet.”

This was fame enough to get a gig at one of Los Angeles most popular New York-styled supper clubs – John Walsh’s 881 Club – despite creating the impression that she really wasn’t into it. And indeed she wasn’t. Julie hated performing in swanky nightclubs. Partially it was because performing in front of an audience terrified her, but it was also because she simply wasn’t a night person.

So much did Julie hate performing that she refused to audition. They gave her the gig anyway.

On her first night performing at John Walsh’s 881 Club, Julie was so petrified that she locked herself in the bathroom.

When she was finally coaxed out and onto the stage she expressed such vulnerability, such a lack of self-confidence, that everybody felt her pain.

Soon she was making records. Soon she was making “Cry Me A River.”

Everyone involved with “Cry Me A River” seems to have been in love with Julie.

It was written by Arthur Hamilton, who claims to have taken her to the senior prom.

Years later, when Julie was married to Jack Webb, Jack was directing Pete Kelly’s Blues, a movie set in the 1920s, complete with jazz and flappers and gangsters and the most boring trailer I’ve ever seen. But also Peggy Lee and Ella Fitzgerald. Peggy and Ella needed songs to sing… Arthur Hamilton wrote songs… so Julie gave her old prom date a call.

“Cry Me A River” was supposed to be sung by Ella in the film, but it got cut. So did Julie and Jack’s marriage, but that was okay. Julie simply moved on to pianist – and Number One supporter – Bobby Troup, who got her that gig in the supper club, and produced her first album. Also, they got married. And they decided that, since Ella hadn’t recorded “Cry Me A River”, they ought to instead.

So “Cry Me A River” was a song written by Julie’s prom date, for a movie starring and directed by her first husband, before ultimately becoming the big hit on her debut album, produced by her second-husband.

Awkward.

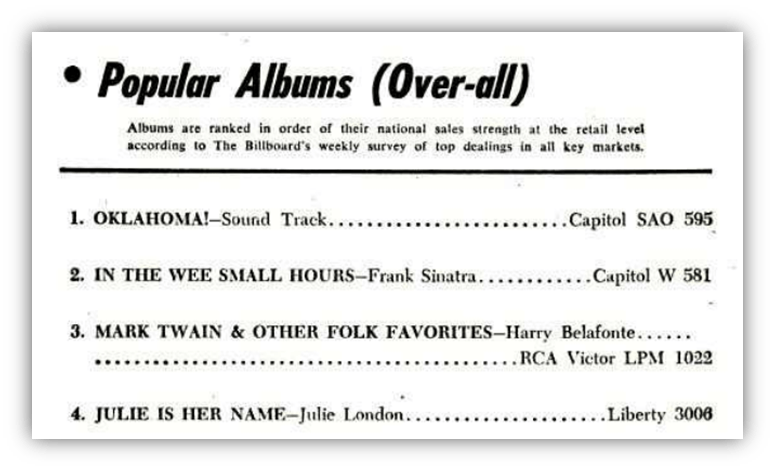

That album – Julie Is Her Name – was a big hit.

It almost hit Number One on Billboard, but was kept off by the “Oklahoma” soundtrack. What’s more, Julie was taken seriously.

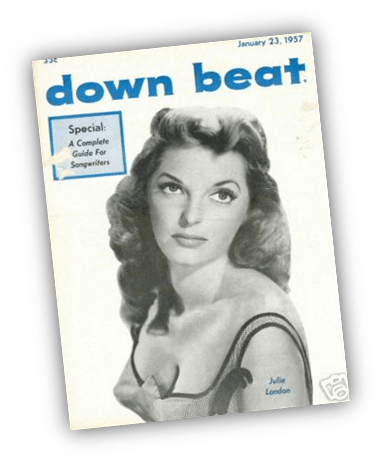

She got on the cover of Downbeat, a serious jazz magazine.

As a serious music publication, Downbeat limited their perve commentary to describing Julie as a “winsome” – that’s a word you don’t read nearly enough anymore – “strawberry-blonde singer” with “not unattractive legs.” Most other publications used more adjectives.

“I always think of myself as a housewife type, but I’m always cast as a bad, wild girl,” Julie would complain.

Julie wasn’t bad, she was just drawn that way. With “Cry Me A River” you get both Julies, her warm tone sounding equal parts as though she’s seducing you, drowning her sorrows, and singing a lullaby whilst she puts the children to bed.

And of course, it sounds enticingly haunting.

So haunting that a year later, this would happen:

That was a scene in “The Girl Can’t Help It”, a “rock’n’roll movie.

It featured Little Richard, Fats Domino, Gene Vincent, Eddie Cochran, and The Platters…

Which featured “Cry Me A River”, even though Julie did not possess a single rock’n’roll bone in her curvaceous body.

In “The Girl Can’t Help It”, a gangster wants his floozie – played by Jayne Mansfield – to become a pop star and hires Julie London’s press agent to turn her into one in six weeks.

He gets the job because he has a reputation of not sleeping with his clients, even though he very clearly wants to.

In an earlier scene of “The Girl Can’t Help It”, Julie London’s agent and Jayne Mansfield have the following exchange

“You don’t want a career?”

“I just want to be a wife. Have kids.

But everyone figures me for a sexpot!

No one thinks I’m equipped for motherhood!”

(I don’t think I need to tell you where the camera pans next.)

Julie London could relate.

& presenting the Official It’s The Hits Of November-ish 1955 Spotify playlist… it’s a very 50s pop (dinner) party playlist from “16 Tons” to “16 Candles”!

https://open.spotify.com/playlist/2VpyGZDdwDb34gMSl0dgRF?si=1ce9f908fbb24696