Those of us of a certain age remember the Space Shuttle Challenger:

Exploding on its way into orbit, instantly killing all seven people on board.

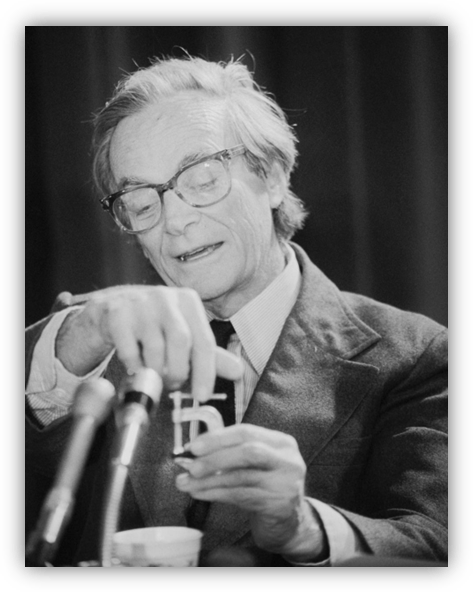

Some of us will also remember a moment during the investigation when a scientist put a small O-ring in a clamp and then into ice water.

When he removed the O-ring from the water and then from the clamp, it was cold and stiff, and it didn’t go back to its original shape.

The decision to launch in cold weather turned out to have caused the disaster. The O-rings hadn’t been tested below 53°F and it was 36°F at the time of the launch. Since the O-rings had been stiffened by the cold, they didn’t completely seal the gaps between sections of the rocket. Gas escaped around the seals and ignited.

Putting the O-ring in ice water was the defining moment of the investigation.

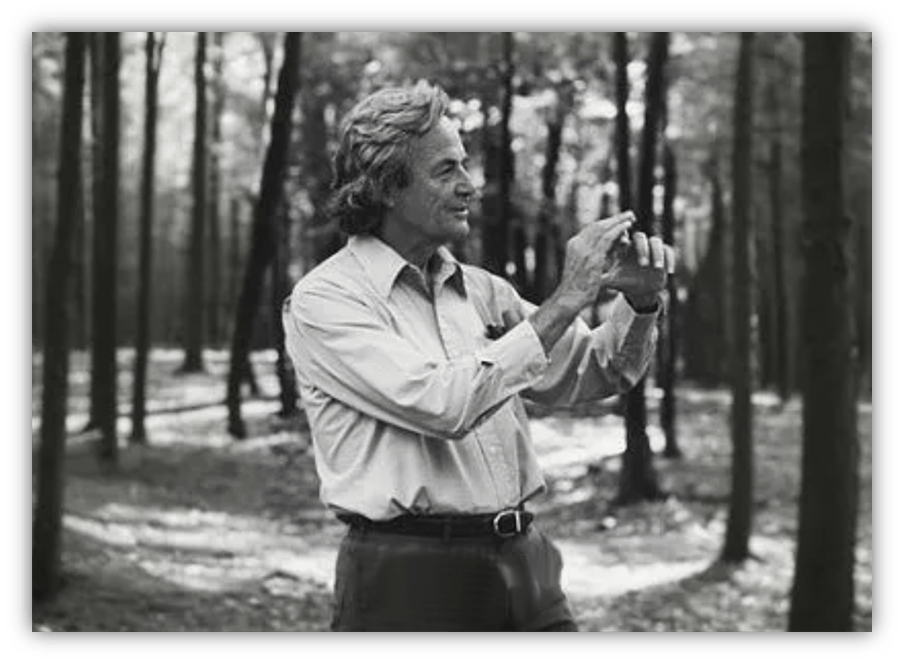

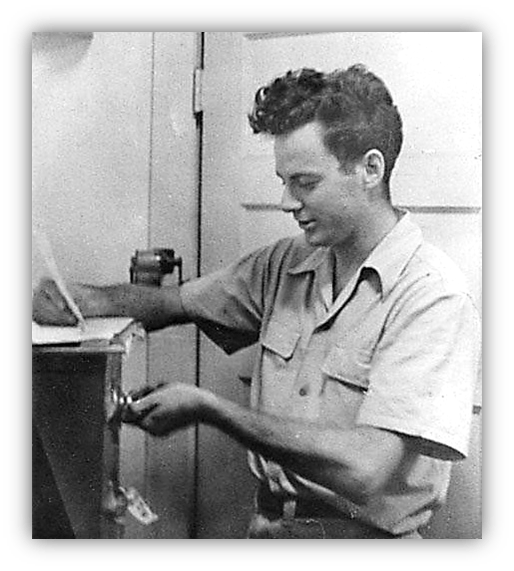

The scientist’s name was Richard Feynman.

His demonstration made him even more famous than he already was.

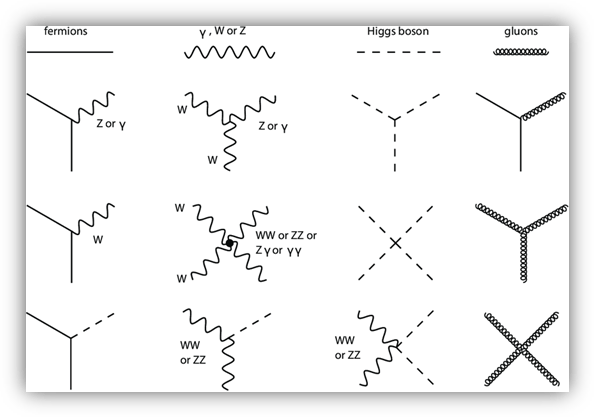

He had shared the 1965 Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on quantum electrodynamics, a field that explains how light and matter interact at ridiculously tiny scales. He taught at Cornell and Caltech, and his “Feynman diagrams” made the quantum world visual and intuitive for scientists.

For us non-physicists, they look like random squiggly doodles:

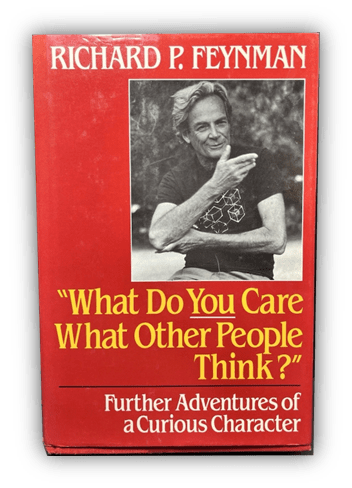

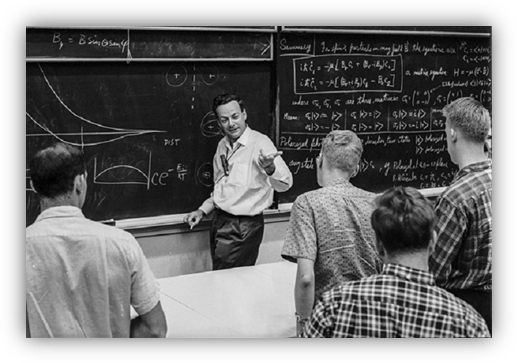

His famous physics lectures are available on YouTube, but Feynman’s legacy isn’t built on physics alone.

It’s built on curiosity, intelligence, and a bit of mischief.

If he wanted to learn about something, he’d feel it, play with it, and sometimes break it just to see how it worked.

Most famous physicists are known for their equations.

Feynman got famous for his, but also the way he thought, the way he taught, and the way he played.

He wasn’t just one of the greatest scientific minds of the 20th century. He was also a safe cracker, a drummer, a prankster, and a man who got deeply interested with a remote Asian republic called Tuva.

Feynman helped design the atomic bomb at Los Alamos, and later regretted parts of that work.

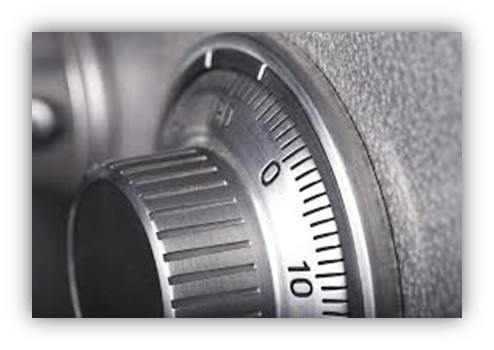

During his off hours there, he fought off boredom by learning to pick locks and crack safes. He didn’t do it to steal anything, he just wanted to prove how insecure the supposedly top-secret file cabinets were.

He would break into the cabinets and leave notes like “I borrowed document no. LA4312 – Feynman the safecracker.”

Or he’d do it anonymously in order to scare people into changing the combinations. “This one was no harder than the other one. — Wise Guy.” And:

“When the combinations are all the same, one is no harder to open than another. — Same Guy.”

We here at TNOCS love music, so the real reason I’m writing about Feynman is that he loved music, too.

He didn’t have what you’d call a “music career,” but he played music — not to perform for crowds, but because he loved the feel of vibrating drumheads under his hands, just like he loved the slide of chalk across a blackboard or the click of a lock tumbling open. It was a sensory pleasure.

He played percussion, starting on bongos and approaching them the same way he approached physics.

He watched, listened, experimented, and treated mistakes as part of the fun. You learn as much from mistakes as you do from successes. Any good scientist knows that. Musicians know it, too.

At Los Alamos, he picked up musical techniques from fellow scientists and soldiers who played casually in the evenings.

Later, in New York, he became a regular at jam sessions in Jazz clubs, where he sat in with local musicians and learned Afro-Cuban rhythms.

Over time he learned to play congas, pandeiros, and whatever else people would let him try.

He wasn’t flashy, but he was a solid player — focused, musical, and a team player.

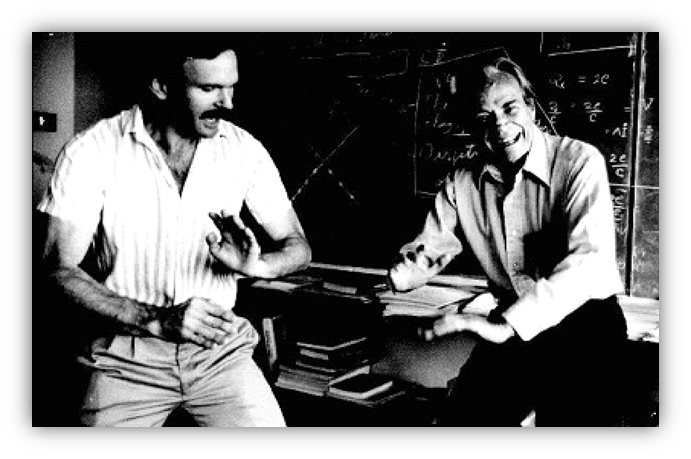

He often played with his friend Ralph Leighton.

The pair even provided music for an all-percussion ballet. Leighton recorded many of their informal sessions and collected Feynman’s stories.

He later released some of these tapes on a CD called Safecracker Suite. It’s available on Bandcamp.

More on Leighton later, but here they are with their song about orange juice.

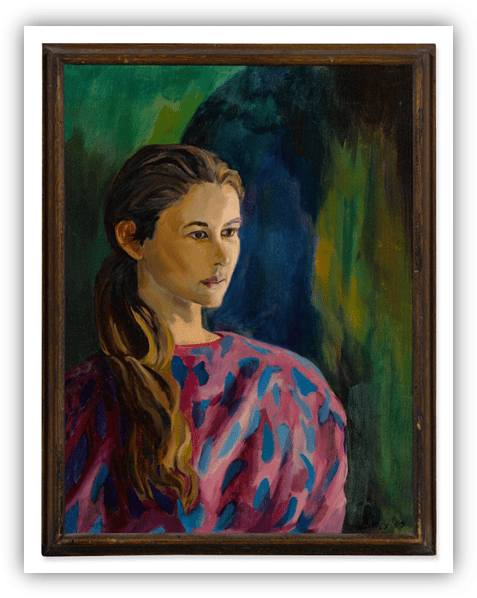

In addition to music, he took up drawing and painting, signing his work with the pseudonym “Ofey.”

He assumed new names for his music and art because he wanted to be judged for that work, and for no one to think he got the gig because he was already famous.

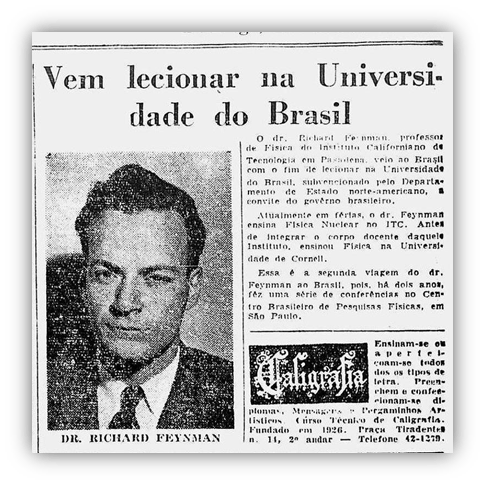

He learned Portuguese so he could understand more at a physics conference in Brazil, and he studied dance so he could move better while drumming. Everything in his life was based on the sheer joy of learning.

He was a good enough percussionist that, while in Brazil, he was accepted into a samba school. As I mentioned in my article about Bossa Nova, samba schools aren’t actual teaching facilities. They’re more like a group, like a school of fish.

He was always good at making friends and somehow became part of his group playing the frigideira, a percussion instrument shaped like a frying pan.

He had never played it before, but little things like that never stopped him.

He didn’t tell the school he was a physicist, just like he didn’t tell his fellow physicists that he was playing in a samba school.

He stayed at a hotel on one of the main streets in Rio de Janeiro, and became friendly with the staff.

He was curious about people and easily became friends with everyone he met.

The head waiter excitedly told him to be there on a particular evening because the Carnival parade would go by right in front of the hotel. Feynman said he had plans and probably wouldn’t attend. The waiter was disappointed.

When the parade went by, there was Feynman in full costume with the rest of his samba school, parading in front of the hotel. He heard the waiter scream, “O professor!” The head waiter found out why Feynman wasn’t able to be there that evening to see the parade.

Because he was in it.

Feynman wasn’t a professional musician, but music gave him a kind of freedom that matched his playful scientific spirit.

He looked at drumming with the same curiosity he brought to physics, travel, and pranks — as a way to connect with people, to understand movement and rhythm from the inside, and to squeeze every possible drop of joy out of being alive.

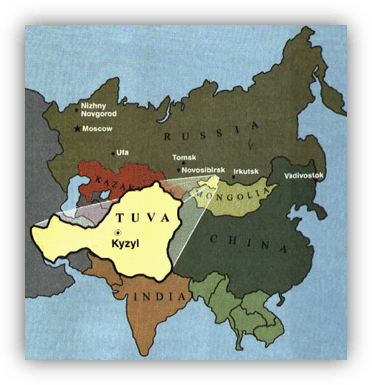

And then there’s his fascination with Tuva.

As a child, Feynman collected stamps and liked the colorful and oddly shaped ones from a country called Tannu Tuva.

The stamps had ornate borders and pictures of camels and mountains.

As an adult, he asked his friends, “Whatever happened to Tannu Tuva?” Nobody knew. So he set about finding out — and that simple question spiraled into a years-long obsession.

Tuva is a tiny, landlocked region deep in central Asia between Siberia and Mongolia.

It’s the most inland point on Earth, as far away from any ocean as you can get.

Tuva had been swallowed up by the Soviet Union and was all but closed to foreigners. That only made Feynman more interested.

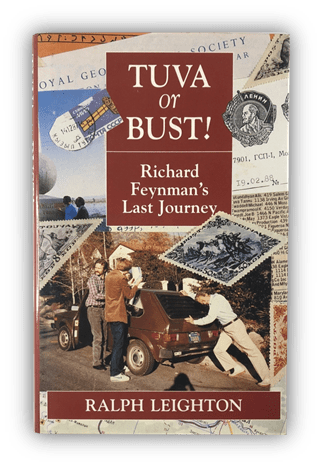

He and Leighton started what they called the “Tannu Tuva project” — an adventure in long-distance letter-writing, bureaucracy-battling, and good-natured curiosity.

The two men learned bits of the Tuvan language, corresponded with embassies, and started the “Friends of Tuva” organization:

Gathering people who shared their fascination with this remote culture.

Naturally, the Soviet government was suspicious of an American asking about a small region in their country, especially a physicist who had worked on the atomic bomb. They eventually — in 1988 as the Soviet Union was starting to crumble — approved his visit, but he never made it there.

Just days before the approval letter arrived, Feynman died of cancer.

Still, his dream inspired others to go.

Leighton later wrote a book about it called Tuva or Bust!, and the “Friends of Tuva” group eventually helped send American musicians to Tuva and bring Tuvan musicians to the United States.

Feynman’s curiosity about stamps helped open the world’s ears to Tuva’s incredible vocal music, but that’s another story. I’ll tell that story next week, but I had to tell Feynman’s story first.