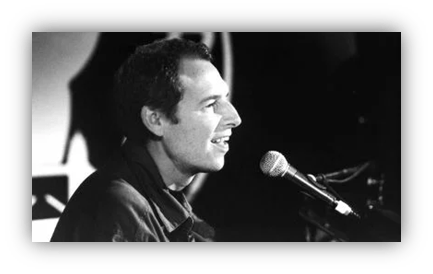

Photo credit: Michael Macor

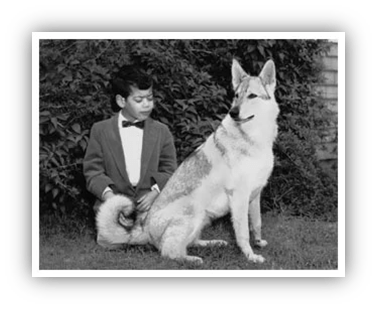

Paul and Babe Pena were each visually impaired.

He was born in 1950 with congenital glaucoma and was completely blind by the age of 20.

We don’t know the severity of her impairment because she wasn’t the famous one. There’s very little documentation about her. We don’t even know how she and Paul met. We do know that they were already married when his music career started taking off.

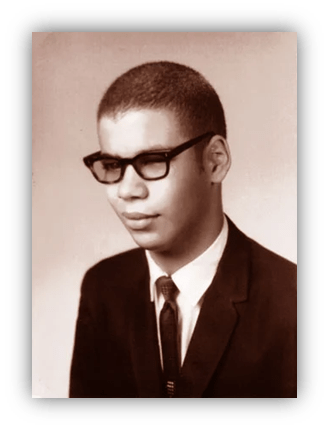

After graduating from the Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown, Massachusetts, he went to Clark University in Worcester.

As a kid, he had learned piano on a baby grand that had been pulled out of the local landfill.

He also took up guitar, violin, double bass, and trumpet.

He gravitated to Blues, Jazz, and Gospel, and studied the recordings of B.B. King, Ray Charles, and T-Bone Walker.

He developed perfect pitch and, by his twenties, was an accomplished guitarist, singer, and songwriter with a soulful, supple voice that could slide from rough growling bass to smooth falsetto.

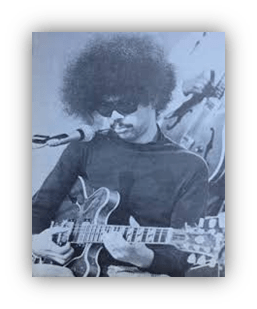

His gigs at local coffeehouses grew into opening shows for the likes of Jerry Garcia and Frank Zappa. He sang bass on Bonnie Raitt’s debut album and took part in the Contemporary Composer’s Workshop, along with James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, and Kris Kristofferson, at the Newport Folk Festival in 1969.

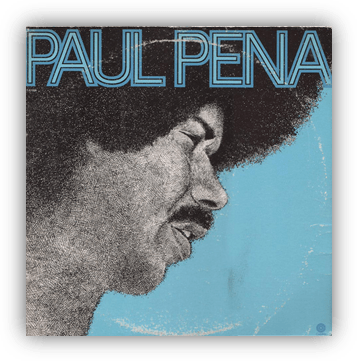

Pena (pronounced PEE-nah) recorded his first album in Boston in 1971, and it came the following year. It didn’t sell terribly well, but the reviews were stellar.

It’s now a hard-to-find collectible.

Paul’s friendship with Jerry Garcia led him to move to San Francisco in 1971.

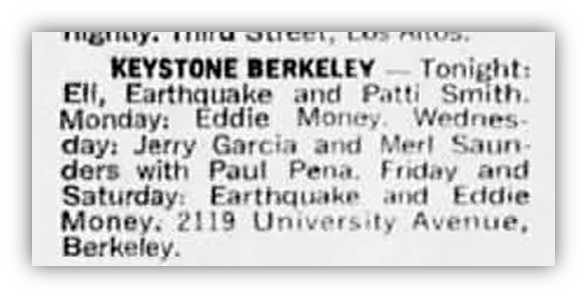

He got involved in the scene around the Grateful Dead and a venue called the Keystone.

He became a regular opener there, often playing before or with Garcia and Merl Saunders. Those gigs put him in front of influential musicians and promoters, and the buzz from fans, musicians, and club owners helped him land a deal with Bearsville Records to make a second album.

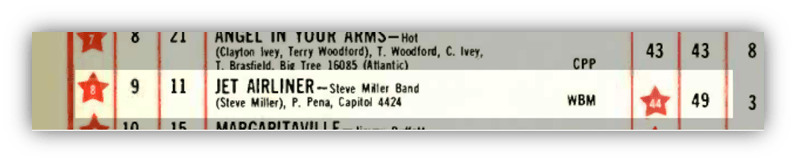

It was produced by Ben Sidran, who played keyboards in the Steve Miller Band.

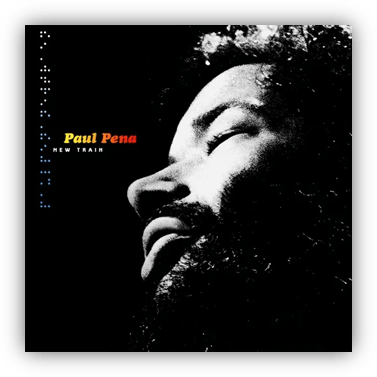

He also played on all the album’s songs. Garcia and Sauders played on two tracks. The album was called New Train.

However, the head of Bearsville, Albert Grossman, refused to release it. Some accounts say Grossman didn’t think it would sell. Others say he was upset that Pena wouldn’t move to New York to be closer to Grossman’s office. Whatever his reasons, he never released New Train.

Sidran gave a demo copy of the album to Miller, who loved it.

The Steve Miller Band covered one of its songs, “Jet Airliner,” and it became a massive hit in 1977.

The songwriting royalties were enough for Paul and Babe Pena to live on for the rest of their lives, which was good because Paul was contractually obligated to Grossman so he couldn’t record for any other label.

Here’s Paul’s original version.

While Grossman’s pigheadedness ended Paul’s recording career, the “Jet Airliner” royalties allowed Paul to play fewer shows so he could take care of Babe as she became progressively more ill over the years. We don’t know when she was first diagnosed or with what, but she was sick throughout the 1980s.

He knew he was going to lose her.

To distract himself from stress, he began learning languages by listening to short wave radio.

One night in 1984, he searched for a Korean language station and picked up a strong signal from Radio Moscow.

It eventually played a sound so strange that he thought his radio might be broken. The sound was musical and almost human, but unlike anything he had heard before — a low rumble with a high, flute-like whistle floating above it.

The announcer said that it was a single person singing two notes at once and that it was the traditional throat singing of the “Tubash people.” Whether that’s actually what the announcer said or whether Pena heard it incorrectly, he spent years trying to find out more about Tubash music.

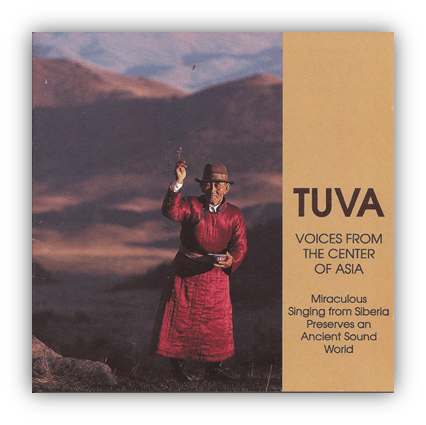

Eventually, a record store clerk found him a copy of Tuva: Voices from the Center of Asia.

It wasn’t Tubash music after all. It was Tuvan. Pena later said:

“So for seven years I asked people, ‘Who are the ‘Tubash people’?

“And no one knew since they don’t exist.”

He wore out the record. With the same determination he had for learning languages, he taught himself how to throat sing.

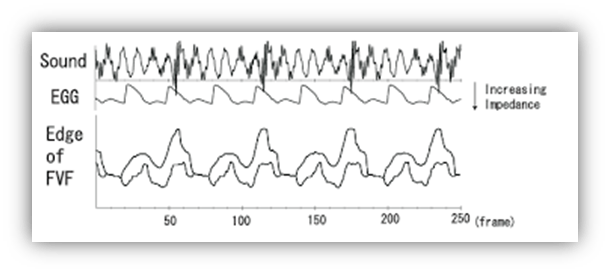

In throat singing, the singer holds a deep low tone in his chest and then shapes his mouth, tongue, and throat to emphasize particular overtones (the natural higher pitches already existing in the sound).

I say “his” because most Tuvan throat singers were male.

Men — especially herders and shamans — passed the techniques down through apprenticeships and public performance. This is changing.

Since the late Soviet and post-Soviet era, women have increasingly learned and performed throat singing.

Likewise, throat singing isn’t strictly Tuvan, and this video shows women from central Asian countries and elsewhere throat singing.

There are several different styles of throat singing.

Some are deep and growly, others are bright and flute-like — but the basic idea is to use careful breath control and mouth shape to make the hidden harmonics stand out. Sometimes singers use circular breathing to sustain long notes.

Here’s a video showing five of the styles.

Pena taught himself several styles and thought being blind gave him an advantage. “Maybe by having to use my ears more than most, I can say that’s coming from that part of the throat or that sort of thing.” Given that he was already an excellent bass singer, he got really good at kargyraa, one of the deepest and most dramatic styles. He said he had a breakthrough while practicing as he was producing a “healthy number” on the toilet.

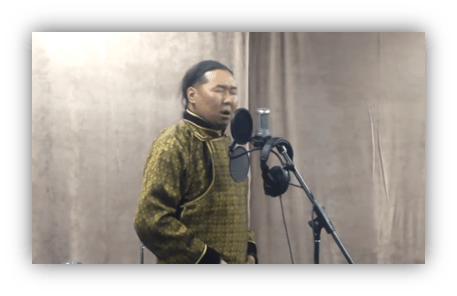

Kargyraa is known for its rumbling, almost volcanic sound:

With both a gravelly bottom and a faint, flute-like shimmer on top.

Over time, Pena developed a remarkable kargyraa voice — dark, low, and resonant, perfectly suited to his Blues background.

He also taught himself the Tuvan language.

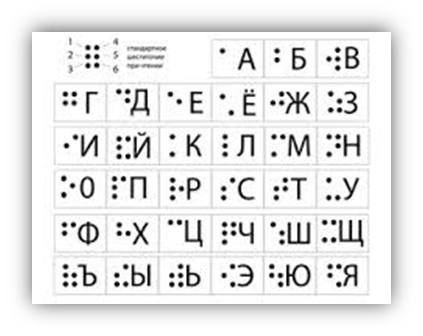

To do that, he had to first teach himself the Cyrillic alphabet and then use his tactile reading device to scan printed Tuvan. There weren’t any Tuvan/English braille dictionaries, so he first translated Tuvan to Russian, and then the Russian to English, using braille dictionaries to convert lines of lyrics into meanings he could memorize.

He gradually learned enough Tuvan to pronounce songs, speak basic phrases, and perform in the language.

He did all of that without a teacher, and mostly by ear and touch. And at the same time, he took care of Babe, whose health slowly deteriorated. She died of kidney failure in 1991.

He continued learning music and languages to fight off depression.

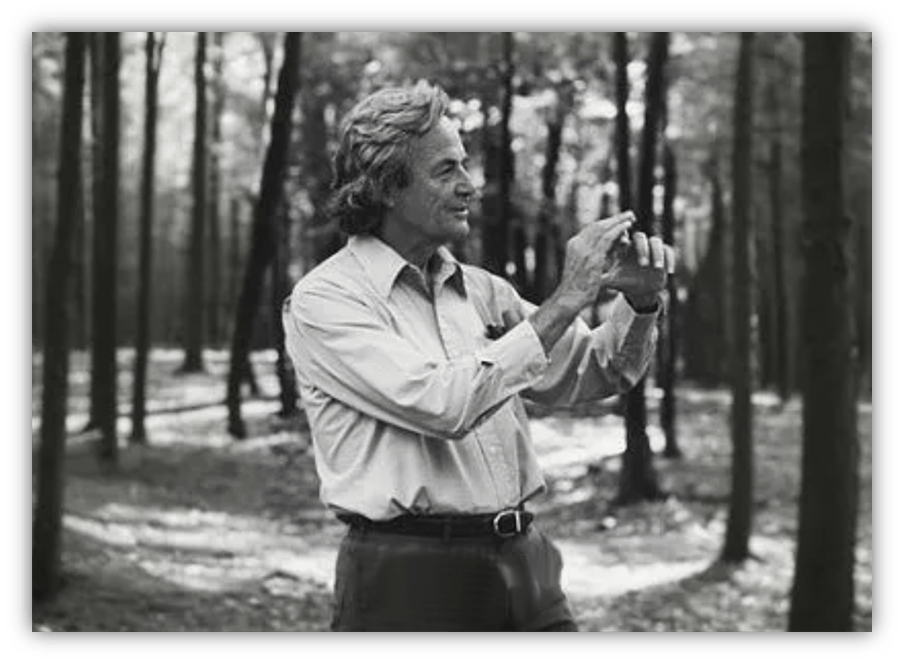

In 1993, Pena attended a concert at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco featuring the renowned Tuvan throat-singing group Huun-Huur-Tu and soloist Kongar-ol Ondar:

One of Tuva’s throat singing superstars.

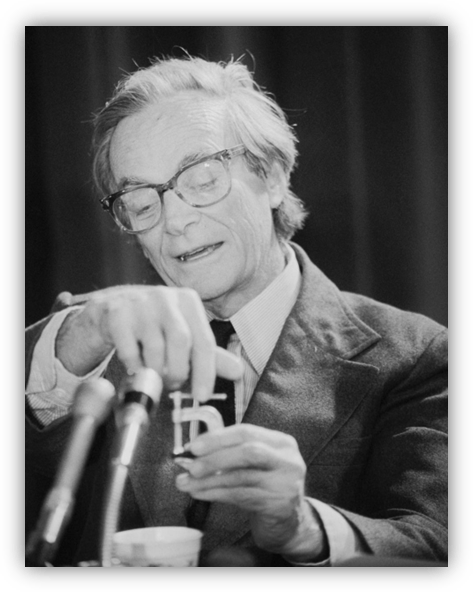

They were on a tour of the United States, and the San Francisco performance was sponsored by Friends Of Tuva, the organization started by Ralph Leighton and Richard Feynman, the physicist I wrote about last week.

Feynman had died a few years earlier, but the organization’s work helped start a relationship with the once isolated Tuva. Americans had already visited the country and its capital city, Kyzyl.

Without Feynman, it’s unlikely that relationship would have happened, given how few westerners had even heard of the place.

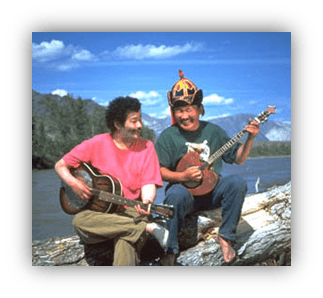

After the show, Pena was introduced to Ondar, and gave a spontaneous demonstration of his own throat singing.

Ondar was stunned.

Not only could this American throat sing authentically, he could speak Tuvan. The two men hit it off instantly, and Ondar invited Pena to sing at the International Throat-Singing Symposium in Kyzyl, a competition held every three years.

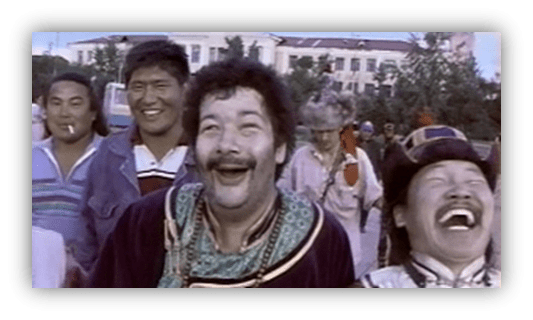

Pena made the long trip, accompanied by friends and filmmakers in 1995.

The trip was documented in a film called Genghis Blues.

It won the Audience Award at the 1999 Sundance Film Festival, and was nominated for the Best Documentary Feature Oscar in 2000. It’s a thoroughly enjoyable movie.

For a blind man, traveling to Central Asia was a journey filled with wonder and sensory overload:

New food, strange instruments, and the stress of the cacophonous symposium. He competed in the kargyraa style and the audience loved him, especially when he spoke to them in Tuvan. He won first place in the kargyraa division and also took home the audience favorite award. They gave him a local nickname: “Cher Shimjer:”

“Earthquake.”

Paul and Kongar-ol Ondar became close friends.

They didn’t get together often but their friendship was the best kind of cultural exchange. They were just two singers connecting through music, combining their native genres.

In 1997, Pena was severely injured after his bedroom caught fire.

A few years later, suffering from diabetes like Babe had, he was misdiagnosed with pancreatic cancer. Only later, in 2000 and after he had undergone chemotherapy, was he correctly diagnosed with pancreatitis.

On the rare occasions he felt well enough to record, he cut songs with influences ranging from Blues to Tuvan to Morna — the national music of Cape Verde, the country his grandparents had immigrated from. Many of these tracks appear on the Genghis Blues soundtrack album.

The popularity of the documentary and its soundtrack led to New Train finally being released in 2000 on a small indie label.

Critical reaction was overwhelmingly positive.

The myth persists that throat singing leads to early deaths, though there’s no evidence to support it. Poorly executed throat singing can cause vocal fatigue, hoarseness, and nodules or polyps on the vocal folds, but none of those are fatal.

Paul Pena passed away in 2005 from pancreatitis and diabetes at the age of 55. Kongar-ol Ondar died after emergency brain surgery in 2013. He was 51.

Feynman and Pena were insatiably curious.

Feynman worked in universities seeking big answers about how the universe works on the quantum level.

Pena worked in nightclubs and studios seeking new sounds and ways to play music.

Feynman taught himself safe cracking, Pena taught himself languages.

And they shared a fascination for Tuva. They never met:

Wow. After last week’s piece, I was looking forward to this week’s. This was even more incredible. And the fact that Pena had a Billboard Hot 100 Top 10 writing credit was the cherry on the sundae of this account. Great job.