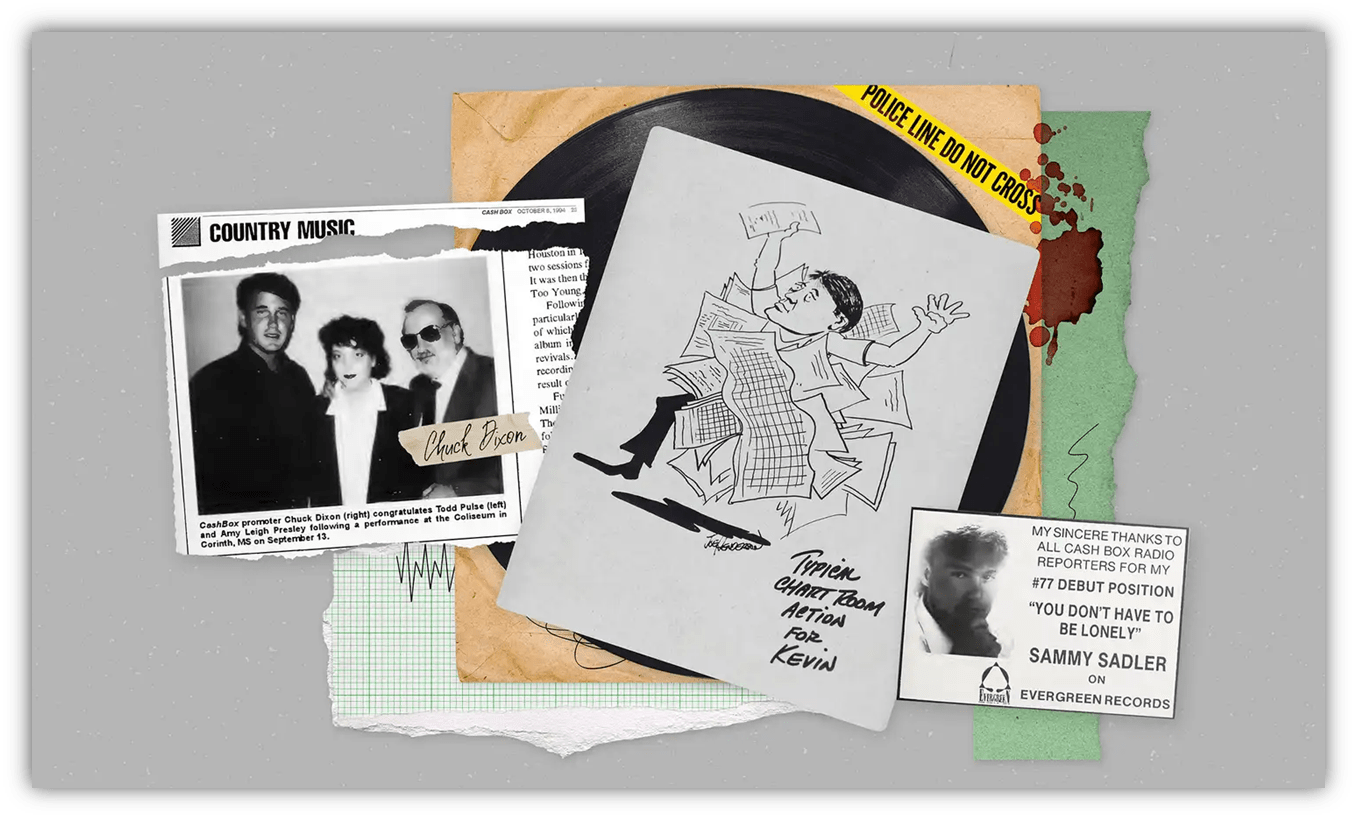

Photo illustration: Andrea Brunty

Earlier this week, TNOCS Contributing Author Music Historian wrote a piece about Cash Box Magazine.

They mentioned a 1989 murder on Music Row in Nashville.

That was 18 years before I moved to Nashville so maybe it’s not surprising that I had never heard of it, but my first job was two blocks away from where it happened, so it seems like someone would have mentioned it in passing. So I looked into it.

On March 9, 1989, Sammy Sadler dropped by the Cash Box office to see his friend Kevin Hughes.

Hughes was working late, so they went out to dinner. On the way back to Cash Box, Sadler wanted to stop at Evergreen Recording Studio so Sadler could use the phone.

Sadler was a promising Country singer and was recording at Evergreen.

He also worked there as a promoter, and wanted Evergreen to pay for a long distance call to his parents in Texas.

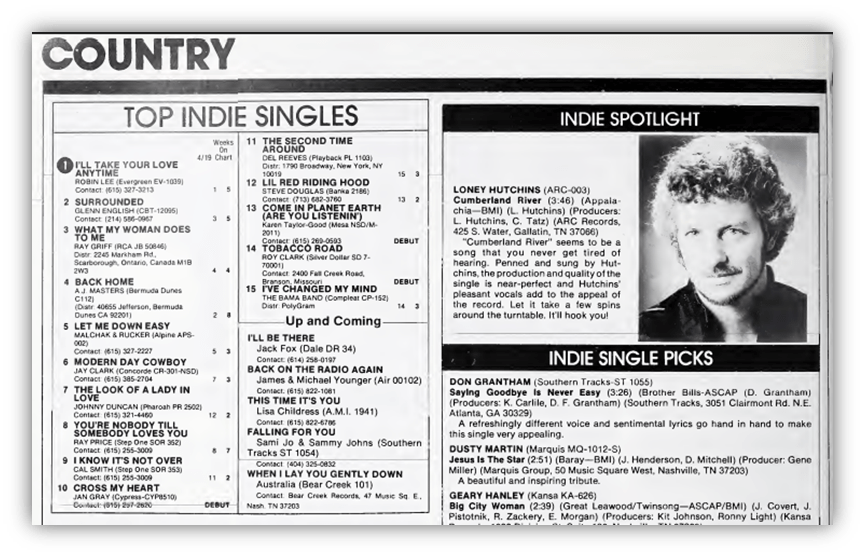

Hughes was the 23-year-old director for Cash Box magazine’s Country/Up-and-Coming charts.

In 1985, he became an unpaid intern at Cash Box while studying at nearby Belmont University.

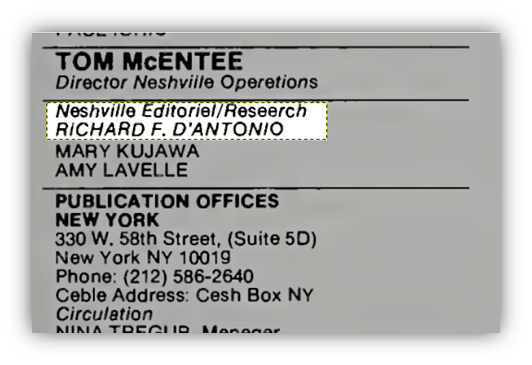

He was put in that role by Richard “Tony” D’Antonio, the chart operations director for Cash Box’s Nashville office.

D’Antonio needed help handling chart data work, interviewed several Belmont students and selected Hughes. Several years later, D’Antonio was fired for using drugs in the office and harassing female employees.

According to a tribute published shortly after his death, Hughes “was soon appointed chart director” because of his drive and dedication. We don’t know the exact date of his hiring, but he was listed as “Cash Box’ Nashville Coordinator for Chart Research” in late 1988.

It was his dream job, having made his own charts at home as a teenager.

He left Belmont to work full time.

As a side note, it’s said around town that a Music Business degree from Belmont means you weren’t good enough as an intern to be hired before graduating.

Hughes and Sadler left Evergreen and walked back to Hughes’s car.

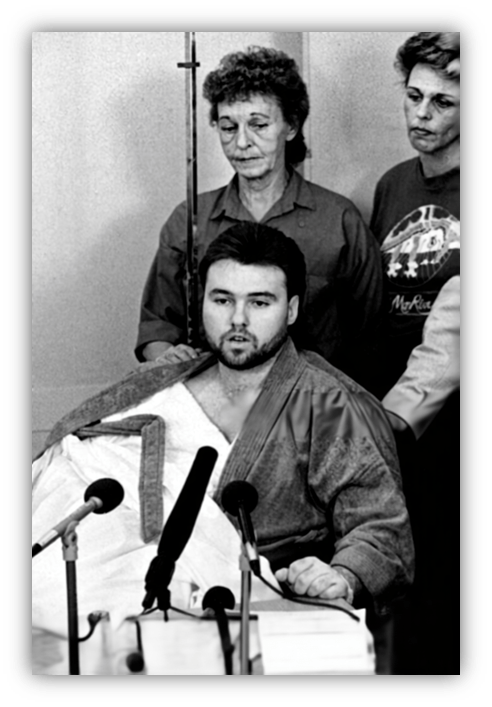

Someone approached the passenger side of the car from the sidewalk, close enough to keep Sadler from closing the door, and shot Sadler in the arm. Hughes jumped out of the car and ran down 16th Avenue shouting for help. The shooter followed him and shot him in the back, and then twice more in the head while he lay face down on the ground.

Sadler survived, though the bullet damaged his nerves. He wouldn’t be able to play guitar for years.

There were five witnesses but none saw the shooter’s face because he wore a black ski mask. The only identifying characteristic they saw was a strange side-to-side limp.

One of the witnesses was an up-and-coming singer named Faith Hill.

She and her husband Daniel rushed to Hughes after the shooter fled. She thinks she heard his last breath.

Kris Kristofferson and Willie Nelson were recording a few doors down. The studio was soundproof so they didn’t hear the shots or the sirens, and they were startled when they took a break and went outside. In the morning, news footage showed them standing next to the crime scene tape.

Police were skeptical of Sadler’s story.

He’s the one who dropped in on Hughes, suggested dinner, and then to stop at Evergreen. Hughes, though he was driving, was just along for the ride. Detectives Bill Pridemore and Pat Postiglione thought it might have been a set up.

What’s more, Sadler’s job as a promoter meant he called radio stations asking them to play Evergreen’s artists.

He also collected their playlists and called Cash Box with the total plays for each of his artists, including himself. It was a conflict of interest.

Police also learned how the Nashville music industry worked, and it was with payola.

- Labels would sign artists, regardless of talent, if they had deep pockets for promotion.

- Managers would bilk artists for thousands and drop them when their money ran out.

- Radio stations would play songs promoters paid them to play.

- Chart directors would accept cash to rank certain songs higher than they deserved.

And any artist or promoter who bought an ad in Cash Box magazine could get their song on the Cash Box chart. A promoter named Chuck Dixon gave Cash Box so much money that industry insiders nicknamed it “Chuck Box.” Dixon and D’Antonio were in contact nearly every day.

Hughes had figured that out and had even accepted a couple payments, but he didn’t feel good about it. He started looking for a new job and told friends back home in Illinois that things weren’t good but would wait until he saw them in person to go into details. He told one friend he thought he was going to be fired.

Cash Box owner George Albert told Hughes to put an artist higher on the chart because the artist had paid for it.

Hughes objected but acquiesced, but made plans to change things.

On the last chart he worked on, he dropped four radio stations that seemed to be altering their reports. All four were promoted by Dixon, and one of the songs that fell off the chart was Sadler’s “Tell It Like It Is.”

While Pridemore and Postiglione still suspected Sadler, another theory developed.

They had found a motel key in the bushes where they believed the shooter had waited for Hughes. A detective named Chuck Lewis did some investigating and found that a man living in the apartment building where the key was found had been having an affair with a married woman. The woman’s husband was jealous and violent, and had confronted the two in a Captain D’s parking lot.

Lewis thought the jilted husband had killed Hughes in a case of mistaken identity, and produced a report with circumstantial evidence. It didn’t hold up to scrutiny.

Pridemore treated it as a distraction. He was certain the corrupt music industry was the motive.

On the morning of the murder, Sadler called Hughes who said he was dropping the four stations from the chart.

He thought their reports were inaccurate because they were changing formats and playing less Country music than they had previously.

Sadler then called Dixon, who didn’t answer. Sadler drove to Dixon’s office and left a note saying Hughes was dropping the stations. Dixon called him back that afternoon, and then called Cash Box several times. The last time he called, he spoke with Hughes directly. It’s not known what was said, but a secretary told police Dixon was upset about the changes Hughes was making.

In the remaining months of 1989, Sadler’s songs appeared on Cash Box charts several times.

The magazine featured ads for his recordings. He was also nominated for Song Of The Year. The problem with that is it was for a song he hadn’t recorded. Sadler has said he doesn’t know who paid for the promotions but it wasn’t him or his family. The ads noted he was promoted by Dixon.

The detectives thought Sadler and Dixon conspired to get Sadler’s songs on the chart, but couldn’t prove it. While the eyewitnesses and industry folks had been somewhat helpful, the detectives asked for help from a wider audience.

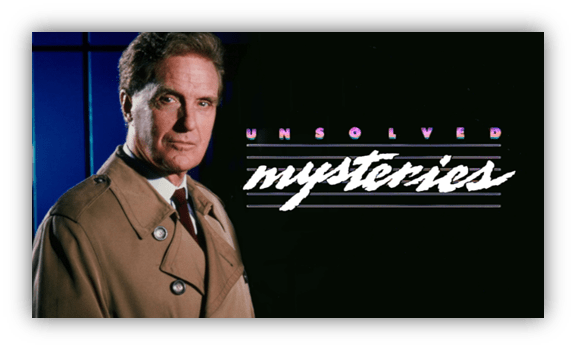

They brought it to Unsolved Mysteries hosted by Robert Stack. The show’s producers interviewed both Sadler and Dixon.

Many viewers called in with suggestions, but most of their ideas had already been disproven. Two people, however, named D’Antonio. Still, the case went cold.

In 1992, the FBI and the Georgia Bureau of Investigation searched a property outside Flintstone, GA, three miles south of Chattanooga.

The house and land had been owned by Steve Daniel, a drug dealer who used his garage for storing drugs and the land for shooting guns. Hundreds of people would practice shooting there.

Confronted with evidence that he had distributed thousands of pounds of marijuana across the south, Daniel became an informant. He implicated D’Antonio as his Nashville distributor and mentioned that he sold a gun to D’Antonio, who had taken some practice shots on the property. It was a .38 caliber revolver, the same type of gun that killed Hughes.

The GBI had Daniel call D’Antonio to set up another drug deal. They recorded the call. In addition to talking about the deal, D’Antonio brought up the murder and said if anyone asked about his whereabouts on March 9, 1989, he was in Flintstone with Daniel until after the 11 O’Clock news.

It wasn’t enough to prosecute D’Antonio, but the GBI got the information to Pridemore. The GBI also said they’d give him access to Daniel once they were done with him, but the wheels of justice are slow and sometimes screech to a halt. Pridemore didn’t get to talk to Daniel until 2002, after Daniel finished his jail time.

Dixon had died of cirrhosis of the liver the previous year. It was a month before Nashville police planned on arresting him on payola charges. Their investigation also showed that he had two families that didn’t know about each other.

When Pridemore asked about D’Antonio, Daniel said, “Man, have you seen that man run?’ He runs like a damn duck.” Eyewitnesses had said the shooter had a weird limp but, again, that wasn’t enough to prosecute.

Daniel no longer owned the Flintstone property but Pridemore got a warrant to search it. There wasn’t much to go on except for the thousands of bullets that had been fired into the woods. It would be nearly impossible, and impossibly expensive, to dig them all up and forensically test them against the bullets pulled from Hughes. Pridemore settled on a single shovelful sample. It had 13 bullets in it.

One of them was a .38, and it matched. With sheer luck, he found the evidence they needed.

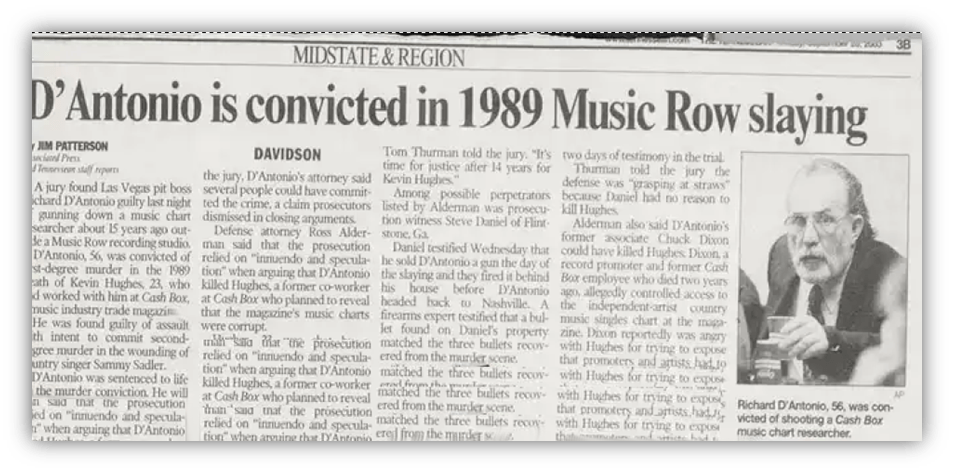

The deceased Dixon was never charged, but D’Antonio was tried for first degree murder. Several promoters and Cash Box employees testified to the culture of chart manipulation at Cash Box, and tensions involving Dixon, D’Antonio, and Hughes.

Daniel testified he sold a gun to D’Antonio, and ballistics matched the gun to bullets from Hughes’s body.

In September 2003, D’Antonio was sentenced to life in prison. He died there in 2014.

Sadler moved back to Texas and regained the use of his arm. He hasn’t forgiven the Nashville police for suspecting him, but returns to town to record. A promoter friend of his suggested doing a memorial concert for Hughes, which Sadler thought was a great idea but a couple years went by and nothing happened.

Sadler ran into the promoter again and asked about it. The promoter said he talked to people and no one wanted to do it because the reason behind Hughes’s death was payola and corruption in the industry.

And that’s a mirror nobody on Music Row wants to look into.

This is a very short overview of the case. If you want more information, The Tennessean has a great eight-part series on it. It’s also available as a podcast.

This was a well-written account of something of which I was completely unaware had happened. Truly awful that the corruption in the music industry led to murder, but also not shocking, sadly. I can see why the industry wants to forget about it, but if they’ve truly moved on and cleaned up their act, they should acklowledge it by at least giving that man a memorial concert. Shameful that it never happened and telling.

In that Music Row job, I wrote software so wasn’t directly involved in the actual music business, but I heard some things that made me the the industry isn’t exactly clean. It might not be through obvious payola anymore, but I’m irked by the condescending attitude that believes it’s clever to slap the “Country” label on anything because the hicks out in the sticks will buy it. It’s a business, I get that, but thinking the artists and fans are hillbilly suckers is amoral elitism. It’s PT Barnum level stuff.

When my Country band broke up, I found my way into scenes that felt more honest and authentic, and never looked back.