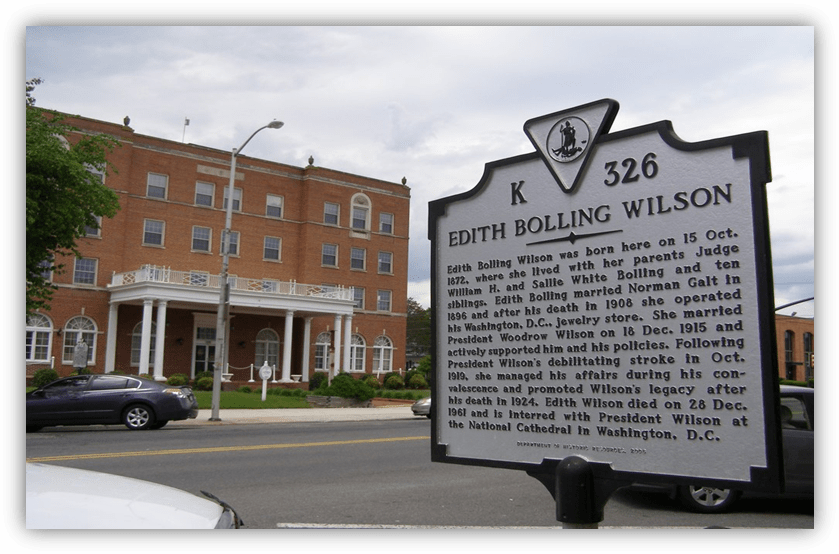

On my recent road trip north for the holidays, I stayed over at the Bolling Wilson Hotel.

It’s a really nice and reasonably priced hotel in downtown Wytheville, VA.

It’s named after Edith Bolling Wilson, former First Lady of the United States.

She was born on October 15, 1872 across the street from what’s now the hotel. The family lived on the second floor over businesses.

She was the seventh of eleven children of judge William H. Bolling and Sallie White Bolling, and she was a direct descendant of Pocahontas through her father’s side of the family.

Growing up in a big, busy home, she did many of its household tasks and helped care for family members. Her formal schooling was limited. She was mostly educated at home by her paternal grandmother and occasionally by her father, rather than in regular schools. She did go to two finishing schools as a teenager, but only briefly. She left the first after one semester because she was unhappy there, and the second closed down after a year due to the headmaster losing a leg in an accident.

Her father decided not to pay for any more of Edith’s formal education. Instead, he focused on her three brothers.

This decision was typical of the era. Families usually invested more in boys’ education because they were expected to grow up and pursue professional careers.

She moved to Washington, D.C. in the early 1890s to live with relatives and take part in the city’s social life. Moving to Washington gave her access to a much wider and more influential social circle than she would have had in Wytheville. It was common and socially acceptable for young women to live with relatives in cities specifically to do this.

It wasn’t partying.

She was positioning herself for friendships, connections, and, yes, marriage.

It was networking and courtship, 19th Century style.

In 1896, Edith married Norman Galt, a successful jeweler in Washington, D.C.

His family owned Galt & Bro. Jewelers, a luxury jewelry store that dated back to 1802. It was known for fine jewelry, silver, and specialty goods.

Its customers included presidents and other prominent figures.

While she definitely married up, it wasn’t a strictly financial arrangement. By all accounts, they really loved each other. Their marriage was affectionate, stable, and based on mutual respect. She didn’t use him for his money and status, and he didn’t treat her like arm candy. They were a true couple.

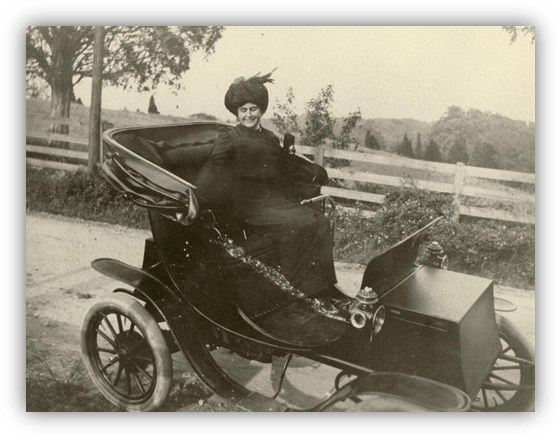

In 1904, Norman bought Edith an electric car.

Electric cars weren’t unheard of in the early 1900s, but they were unusual and high-status.

It was expensive — about $1,600 in 1904, which would be roughly $50,000 in today’s dollars.

They were especially popular in urban areas and among affluent buyers because they were clean, quiet, and easier to operate than gasoline cars of the era — which often required hand-cranking and manual gear-shifting.

Anyway, being a woman driver of an electric car in Washington in 1904 was rare enough to draw public attention — especially since relatively few women even had licenses at that time.

There are stories of Edith zipping through town streets with style and confidence, at times drawing attention simply by virtue of being an early female driver.

It added to her celebrity.

Edith and Norman had an only child who died in infancy. Norman himself died in 1908, leaving Edith wealthy and socially prominent in the capital. She inherited the store and oversaw it, with the help of a manager she hired, until the 1930s, when she sold it to her employees.

She began living her new life in Washington.

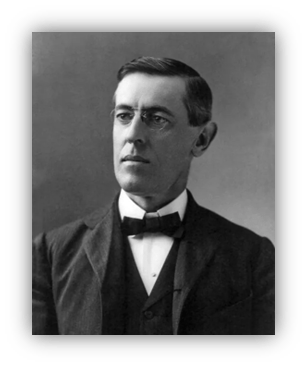

In March 1915, she was introduced to President Woodrow Wilson, who was mourning the death of his first wife, Ellen Louise Axson Wilson.

They had been married for nearly thirty years.

She was a painter and continued to paint in the White House while advocating for better housing and sanitation in poor neighborhoods of Washington, D.C.

She died of chronic kidney inflammation, after a long decline. Some historical accounts say that, as her health was failing, Ellen expressed a wish that Woodrow live well and remarry someday. She died on August 6, 1914, at age 54.

Woodrow Wilson was grief-stricken.

But when he and Edith met, what followed was what can only be described as a whirlwind romance.

Neither was seeking a new relationship but they fell in love. He proposed within weeks but Edith did not immediately accept. She was cautious about moving quickly into a new marriage, in part because he was still grieving.

Besides, she was a successful, wealthy widow running her own affairs:

Including overseeing her jewelry business, traveling in Europe, and driving her own electric car around Washington. Relinquishing that independence to become the nation’s First Lady, with its expectations and public scrutiny, would be a major life change.

We have some letters the two exchanged, and Woodrow, like any good politician, could be persuasive.

He wrote not only about their love but about sharing the burden of the presidency. He didn’t want to do it alone and knew she was up to the job of First Lady. His letters said,

“God has indeed been good to me to bring such a creature as you into my life.”

And:

“Every glimpse I am permitted to get of the secret depths of you I find them deeper and purer and more beautiful than I knew or had dreamed of.”

And:

“I wish you would come to me without reserve and make my strength complete.”

Though Edith initially hesitated, largely because of the short time since his first wife’s death and because she wasn’t sure she knew him well enough, her letters back show that she did actually love him. In her replies she wrote about how his love “fills me with bliss untold,” and how she longed to be close to him and support him.

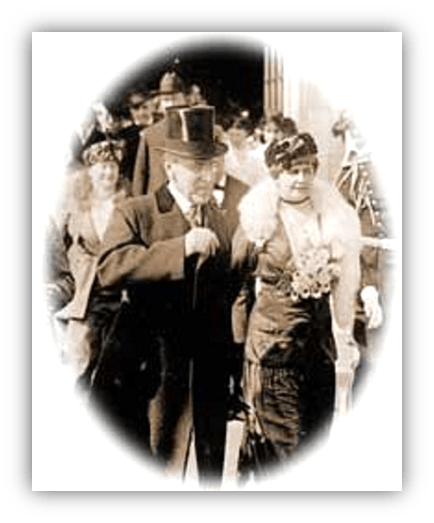

They were married in her Washington home on December 18, 1915.

That made Edith the First Lady of the United States as Woodrow led the country through the final years of World War I and into peacetime.

Traditionally, the First Lady’s role was focused on social functions and ceremonial duties, but Edith did more than host dinners. She volunteered with the Red Cross and encouraged Americans, especially women, to support rationing and conservation efforts during the Great War.

As part of that conservation effort, she brought sheep to the White House lawn.

At a time when manpower was needed for the war and war-related industries, using sheep instead of groundskeepers reduced labor costs.

More importantly, it reinforced the message that everyone — including the First Family — should economize.

The groundskeeping staff didn’t cost much in the grand scheme of things, but the wool shorn from the sheep was auctioned, and the proceeds — about $52,000 in total (roughly $900,000 today) — were donated to the American Red Cross and other war charities.

That’s significant money for a charity, and it made the Wilson’s look good, too.

The sheep didn’t change public policy or alter the outcome of the war, but this was an early example of optics done well — practical enough to be real and visible enough to be memorable. It showed that symbolic politics can model behavior without passing laws, and that Edith understood public perception and messaging.

In December 1918, she became the first First Lady to travel to Europe while her husband was in office, accompanying him to the Paris Peace Conference as World War I wound down.

By being involved in national affairs at a time when few women were, she became a symbol of women’s ability.

She didn’t champion women’s suffrage early on — in fact, she did not initially support the movement — but simply by being capable she showed that women should have a say in who runs the country.

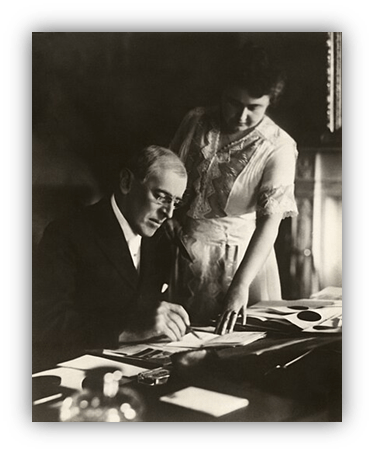

While on a tour to promote the Treaty of Versailles and the League of Nations, President Wilson suffered a major stroke that left him paralyzed on one side and unable to function fully as president. Instead of him stepping back, Edith stepped forward.

The details matter here.

Wilson’s condition was kept secret from the public, and Edith controlled who knew what. She reviewed all communications to and from him, deciding what was important enough to bring to his attention and what could wait. She often summarized documents verbally when he was too weak or exhausted to read. She acted as a gatekeeper, limiting visits from Cabinet members, senators, and even his own senior staff officials.

Because of this extraordinary role, some people — both then and since — have called her the “secret president” or “the first woman president.”

Titles like that are a little misleading. She never had constitutional authority, but controlling information is itself a form of power.

She later called this period a “stewardship,” insisting she never made policy decisions herself — merely decided what her husband should see and when. Historians generally back her up, saying her influence was real but stopped short of making policy.

By deciding who was allowed to speak to the president, which problems reached him, and which crises were delayed, Edith indirectly shaped outcomes.

She was the most powerful First Lady up to that point, and operated in a constitutional gray area because there was no formal process for declaring a president incapacitated.

All of this happened before she had the right to vote.

Edith was aware of the danger of even appearing to overstep her role.

She was careful to frame her actions as protective, and she avoided even hints of taking independent authority. Her caution itself suggests she understood the constitutional stakes.

Her “stewardship” exposed a dangerous gap in the Constitution. At the time, it only said that if a president was unable to serve, the vice president would take over. It didn’t explain who decides the president is incapacitated, how that determination is made, and what happens if the president can’t — or won’t — admit it.

And that gap eventually led lawmakers to create the 25th Amendment.

But not right away. Woodrow Wilson was just the first such case of a diminished president. Franklin Roosevelt governed while seriously ill with heart disease during World War II. Dwight Eisenhower had a heart attack, stroke, and surgery while in office. And John Kennedy concealed major health problems.

So the question remained: Who’s in charge if the president can’t function?

In 1967 — finally — the 25th Amendment was ratified. It detailed how a president can declare himself unable to serve, or his cabinet and vice president can make that declaration.

It also allows for a temporary and reversible transfer of authority, such as when a president is under sedation for a medical or dental procedure.

No president has been removed from office under the 25th Amendment. Yet.

Woodrow Wilson’s presidency ended in 1921 and he died three years later.

Edith devoted the next four decades to preserving his legacy. She helped manage his papers and worked with biographers. She had the Woodrow Wilson House in Washington made into a museum and worked to preserve her own childhood home in Wytheville. I visited the museum there, across the street from the hotel.

She attended major events like John F. Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961, just months before her death on December 28, 1961 at age 89. Fittingly, on what would have been Woodrow’s 105th birthday. She was buried beside him at Washington National Cathedral.

While previous First Ladies like Abigail Adams and Dolley Madison were influential behind the scenes using charm, hospitality, and persuasion, none used actual administrative power. Edith Wilson’s use of her power didn’t become a model for future First Ladies. It was a warning to fix the Constitution.

After Edith, First Ladies became more visible and active in different ways.

- Eleanor Roosevelt dramatically expanded the public role of the First Lady, holding press conferences and advocating for civil rights and social reform.

- Lady Bird Johnson was deeply involved in political strategy, editing speeches, and promoting legislative policy, especially environmental standards.

- Hillary Clinton sat in on policy meetings and led health care reform efforts. Her role was formal and assigned, but that role was more involved in policy than any other First Lady besides Edith Wilson.

Basically, before Edith, First Ladies influenced their husbands. After Edith, First Ladies influenced public opinion, policy agendas, and culture.

Edith Bolling Wilson changed what a First Lady can be.

Her authority came from circumstance, not ambition, but it was real. She could have taken much more power than she did, making decisions for the president without consulting him, but she didn’t. She had integrity, restraint, intelligence, wisdom, and an allegiance to the Constitution.