How did the US and other United Nations foster a culture of freedom in the decades following World War II?

That’s the broad topic of my new series.

The entries here will be posted on more of an ad hoc basis than the Dude series.

It will also be more inclusive topically, ranging from art to education to politics, really anything that tickles my fancy. My primary focus will be on the United States, but I will also cover other nations from time to time. Enjoy!

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt promoted his New Deal policies in the 1930s, he made sure to use art to communicate his vision to the American public.

From 1933 to 1943, FDR would pour more than 37 million dollars into funding for public art. Most of the commissioned works were murals and sculptures for buildings such as post offices and court houses.

And most of those works were simple, idealized depictions of American communities at work, done in a Social Realist style. In other words, their role as national propaganda was readily apparent.

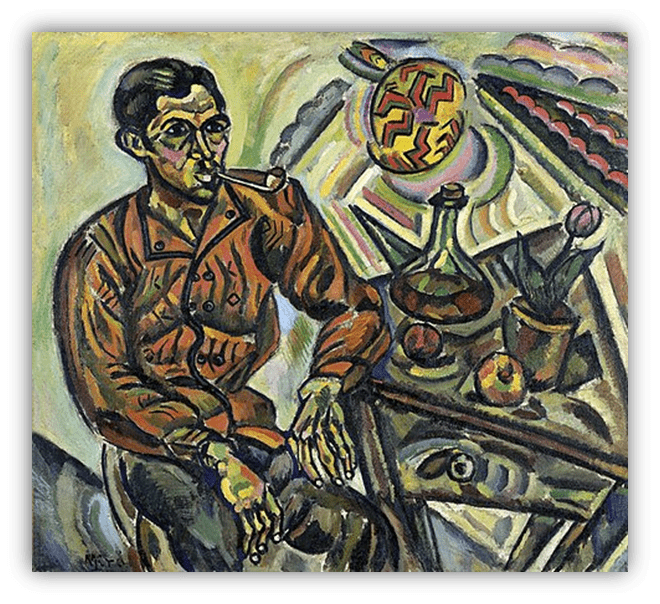

Sternberg, 1939

And then of course came the second war to end all wars. The end of that conflict was to be the dawn of a new day for Western democratic nations. Yet there was a new enemy to contend with: the Soviet Union. Stalin’s regime was viciously authoritarian, but the Soviets were skilled and quite aggressive in their own efforts in propaganda.

Their campaigns were designed to sell communistic society as the best option for global justice and peace.

Given this new opponent on the world stage, it made sense for the US to try to stand out as a cultural epicenter for artistic innovation, individual expression, and the value of freedom.

And yet, it was undeniable that the art of FDR’s New Deal era happened to strongly resemble the Social Realist art that the Soviets used for their own national propaganda.

Not a good look, guys.

So, in the late 40s and early 50s, the US would turn to a different type of art for national branding: the avant garde.

Starting in 1944, the US federal government would make it a priority to fund modern art centers, exhibitions, and art criticism publications, to spread ideas of liberal individualism all over the globe.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York was a crucial asset for this effort.

Its president, Nelson Rockefeller, served in Roosevelt’s administration, and he referred to MOMA as “weapon of national defense.”

Unfortunately, Congress did not agree with the use of federal funds to promote left-wing weirdos. And so, the effort had to go underground. The Central Intelligence Agency was founded in 1947, and one of its first activities was the covert funding of modern art initiatives.

Naturally, this was a great time to be in the arts world. American art curators suddenly had the means to support and elevate whoever they deemed to be the visionaries of this new era.

So what was to be the look of this Bold and Free America? Based on who first gained attention and influence in the years after the war, this was our new national iconography:

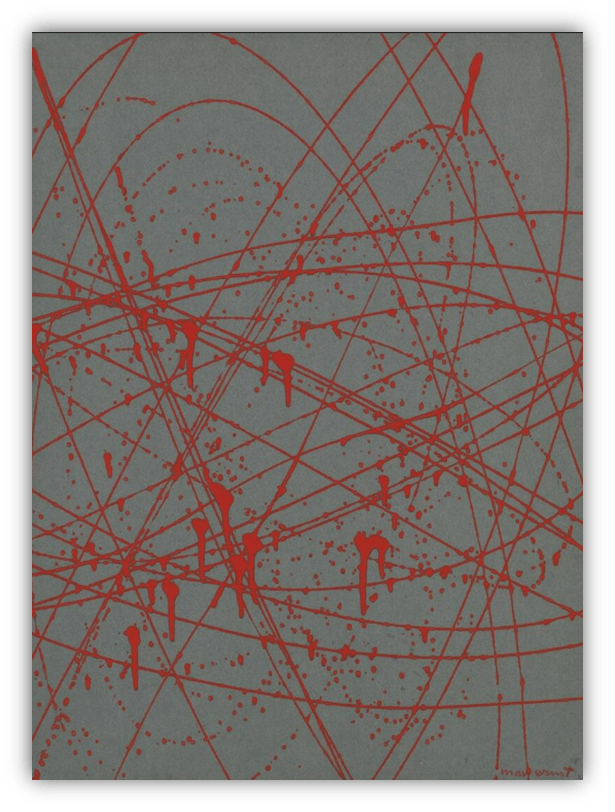

Pollock, 1947

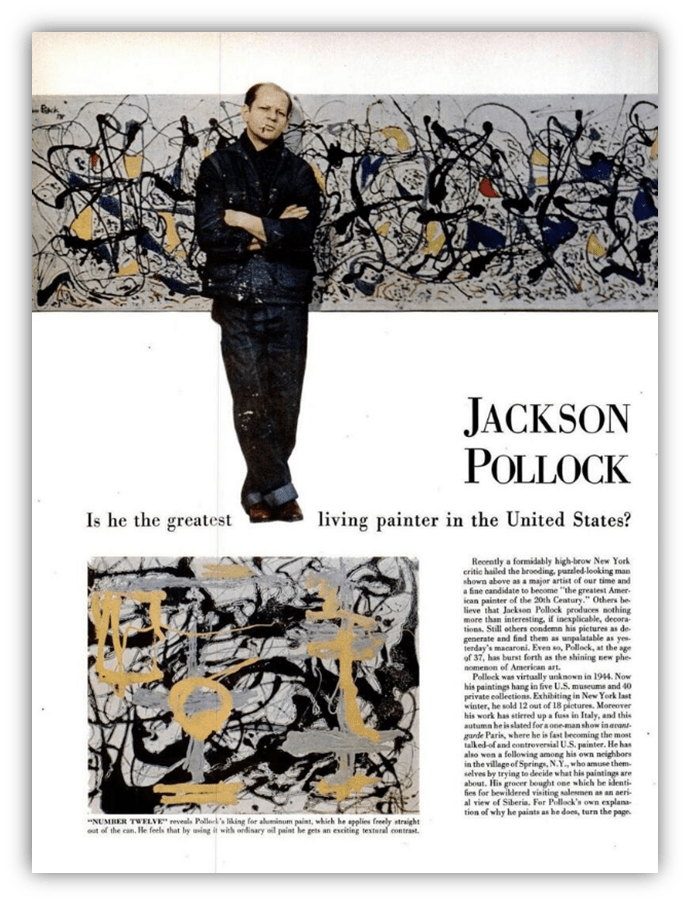

Yes, America’s first major painter laureate was none other than Jack the Dripper himself, aka Jackson Pollock.

Pollock had been living and working in New York City since 1930.

He even contributed to some murals for Roosevelt’s Federal Art Project, albeit in that older Socialist Realism style.

As he continued to develop his approach, he began to incorporate influences from the two most prominent European styles of the modern era: Surrealism and Abstract painting.

As covered in my Dude, Where’s My Van series, the Surrealist painters relied on automatic approaches to generate their bizarre images.

For instance, Max Ernst would rub charcoal and paper against various surfaces to yield interesting patterns, which served as the initial inspiration for dreamlike images to paint.

In the early 40s, while exiled in America, Max Ernst tried punching holes into cans of paint, then swinging them around on strings to unleash jets of color onto his canvas. This was perhaps the closest precursor to what Pollock would soon bring to the art world.

Ernst, 1942

In 1936, Pollock attended a workshop by Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros, and it was there that he learned various automatic techniques of the Surrealists.

While the Surrealists tended to use automatism as the starting point for a pictographic design, Pollock began to adopt a process of capturing movement and fluidity in his strokes without thinking about any representational image.

His first real breakthrough in this vein was his 1943 piece Mural, commissioned for Peggy Guggenheim, who was married to Max Ernst at the time. This was a gargantuan painting: 8 x 20 feet! Pollock had to knock out a wall in his small apartment just to paint the thing. At this point, he was still using strokes on the canvas rather than drips, but it’s otherwise the perfect herald for his signature style.

Pollock, 1943

Like the abstract artists, Jackson’s mature work did not traffic in conventional images or scenes. Yet even Kandinsky and Mondrian paintings could be said to have figures and backgrounds. Pollock ushered in an era where even those conventions were obscured beyond recognition.

Viewers of his paintings may be tempted to tease apart some figure from the swirls and splatters, but there are no real images to be gleaned.

Instead, what we witness is a vibrant record of the paint’s movement as it danced upon the canvas.

Pollock and his peers at the time are sometimes called Abstract Expressionists, because they expressed their inner worlds through non-pictoral, non-symbolic paintings.

They were also called Action Painters, because their work captured and centered the process of painting as a focus in its own right.

Harold Rosenberg, who coined the term, may have been inspired by the Existentialist philosophers popular at the time: Jean Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir argued that the so-called “inner life of the mind” was nothing but BS; all that mattered were the actions that one took, and how one was defined by those freely taken choices.

If Pollock’s paintings could be said to represent anything, that type of open-ended, action-centered philosophy of free will is perhaps the best candidate available.

Not everyone lumped into the movement fit the descriptions quite so well as Pollock did.

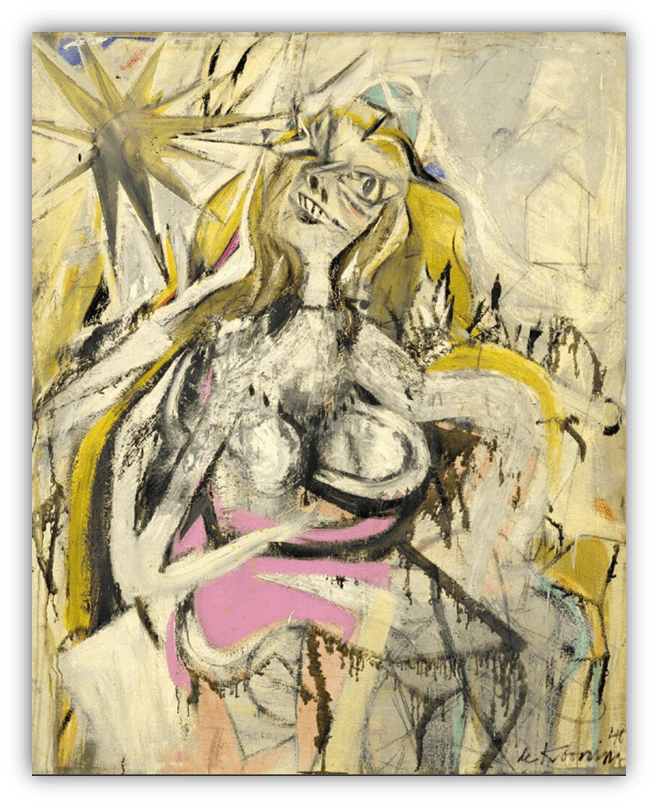

For instance, William De Kooning sometimes had recognizable images in his works.

De Kooning, 1949

Franz Kline evoked recognizable emotions like despair and anxiety:

Kline, 1949

Mark Rothko was more of a proper abstract artist, perfecting the capture of universal human experiences through the most minimal of visual cues:

Rothko, 1949

But importantly, Pollock was the first in this circle to find fame, and so in many ways his vision was the one to which everyone else was compared. It was a movement very much defined by the long shadow of his gigantic murals.

But let’s not veer into hero worship. Most of the great Abstract Expressionist painters were anything but saintly.

Pollock was a raging alcoholic, prone to anger and violence, and he killed himself and another passenger on the road while driving in a stupor.

De Kooning and Rothko were also alcoholics, and Rothko took his own life. Collectively, the lives of these tormented souls can serve as a warning about the perils of dogged individualism without the tethers or supports of a larger community.

Still, their work is potent for the very fact that they didn’t impose a radical agenda upon their audiences. Instead, we’re invited to join a conversation about their meaning and significance.

AI generated photo illustration

That’s the ideal that the US government wanted to fashion as their national propaganda. The goal wasn’t to convey any particular message through a particular painting, but instead to invite citizens to investigate, to interpret, to converse, and even to disagree.

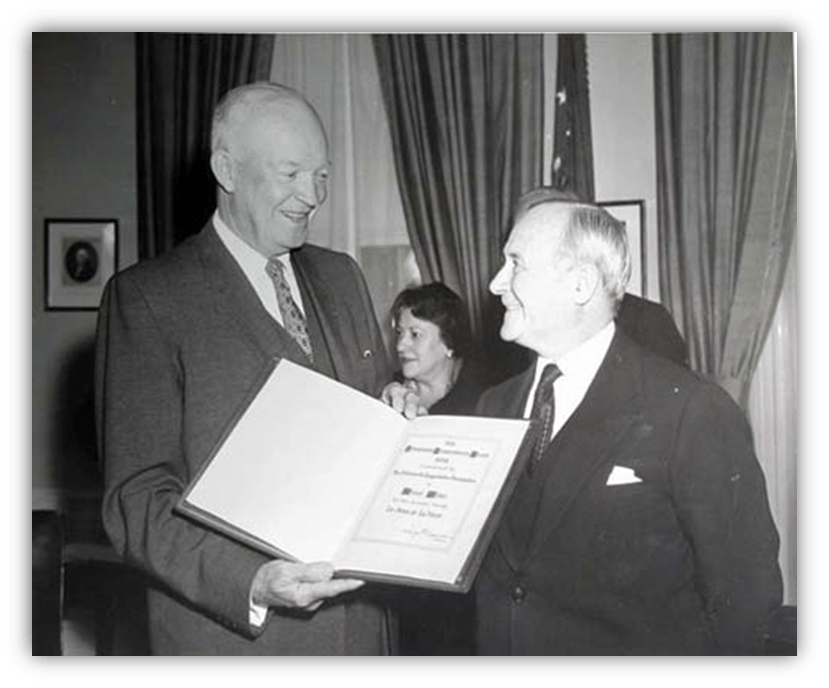

President Eisenhower put it nicely, in a speech he gave for MOMA’s 25th anniversary:

“For our Republic to stay free, those among us with the rare gift of artistry must be able freely to use their talent. Likewise, our people must have unimpaired opportunity to see, to understand, to profit from our artists’ work.”

As long as artists are at liberty to feel with high personal intensity, as long as our artists are free to create with sincerity and conviction, there will be healthy controversy and progress in art. Only thus can there be opportunity for a genius to conceive and to produce a masterpiece for all mankind.

But, my friends, how different it is in tyranny. When artists are made the slaves and the tools of the state; when artists become chief propagandists of a cause, progress is arrested and creation and genius are destroyed.

Let us therefore on this meaningful anniversary of a great museum of art in America make a new resolve. Let us resolve that this precious freedom of the arts, these precious freedoms of America, will, day by day, year by year, become ever stronger, ever brighter in our land.”

Not gonna lie, every time I read the title of this first entry, I sing this:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u31FO_4d9TY

https://youtu.be/6Q3WuhV5wik?si=cCxewlzl9la_wVvT

If only sampling was free for all…

The more I learn about Eisenhower, the more I like him.

Will this series talk about more recent moves to defund the arts?

Yeah, I agree. His tampering in Iran was not cool, but all in all, he was a great President. More forward thinking than he was given credit for. Maybe that’s why conservatives at the time suspected him of being a commie.

I have been trying to hold back on too much explicit roping in of contemporary issues, as I want to invoke the spirit of the time to the extent that I can. But rest assured, those current parallels are present in my mind when writing these. And who knows, maybe I’ll get there eventually…

Ultra conservatives back then suspected EVERYONE of being a commie.

Dude built the interstate highway system and had a top marginal tax rate of 91% during his administration (currently highest tier is 37%). By today’s standards, he was a certified commie.

#TheBirchersWereRightAllAlong?

In Hawaii, every ten miles you travel is like twenty-five on the continent. But every May, I make the thirty-two miles journey to the other side of the island to support my friend’s middle school craft fair: Dogs made out plaster, sometimes cats. In the upcoming three months, it’ll be my fifth year.

My friend recently quipped: “Cappie”, for crying out loud, move to the mainland. Everybody is here to support the kids and rescues. I know you care about stuff, but the main reason is that you’re worried about the National Endowment of the Arts being defunded, right? Chill, bro.”

He’s right.

I had no idea of the history of the arts under FDR. Reading the description of the artistic vision in the pre WW2 period and seeing those examples i thought it sounded remarkably like communist the Soviet Union propaganda. Turns out I was on the right page. Quite the eye opener and I can totally understand why that aspect might not be celebrated so much given the cold war.

I do like some Pollock, De Kooning and Rothko. Shame that as people they lived upto the tortured artist trope.

Look forward to learning plenty more.

It’s a trope for a reason. There’s plenty more where that came from, unfortunately.

The shift away from Socialist-affiliated art wasn’t just in murals and paintings, it was in music too. Composer Aaron Copland started out as avant garde, then developed a more sentimental populist style during FDR’s time.

But then suddenly, his work was regarded as outdated at best, suspicious at worst. Scoring one for the team was just so passé…

How strange, the leader of the current party of book banning said those words back in the day.

Sadly, that’s not the worst of it. The party of Lincoln seems to have real problem with questions about the cause of the Civil War. Over the years, that cause became Lost to them…

The book banning made me so angry, I read five Judy Blume books. And there are notes in the marginalia.

Oh, no. I’m going to spontaneously combust. I can explain what happened after FDR’s New Deal. But I’ll stay on topic.

I’m a philistine. I don’t get Jackson Pollock. It’s embarrassing to admit. But as my professor once told me: I don’t care if you like it or not. Focus on the text. It was my first year in college(summer session), not community college. In community college, they let you speak in the first person.

Well, I can’t say I’m a huge fan myself. But importantly, I have never seen any of his actual paintings at a museum. I think that’s important for a lot of modern art. The size of them, the textures, the dizzying forest of details–all of that stuff probably comes together to hit viewers a lot harder than if they’re looking at an image in a book or on a screen. Walter Benjamin knew what he was talking about, though I feel like he didn’t lament the diminishing of art via reproduction nearly enough.

And also: I gained a good deal more admiration for his work while researching this piece, so thanks, FREE4ALL project!