If you read my baker’s dozen novelty songs from the ’70s and ’80s, you might wonder why there’s nothing from country/pop goofball Jim Stafford. Part of it is that, of his six top 40 hits, I find one truly stupid (“Your Bulldog Drinks Champagne”). Two (“Wildwood Weed” and “I Got Stoned and I Missed It”) are drug satires that just didn’t click with me, and one (the classic “Spiders and Snakes”) isn’t really a novelty song, though it is funny in the way that 8-year-old boys appreciate. That leaves his first chart hit, “Swamp Witch,” a song I’ve never heard (a distinction it shares with his No. 102-peaking “Cow Patti”).

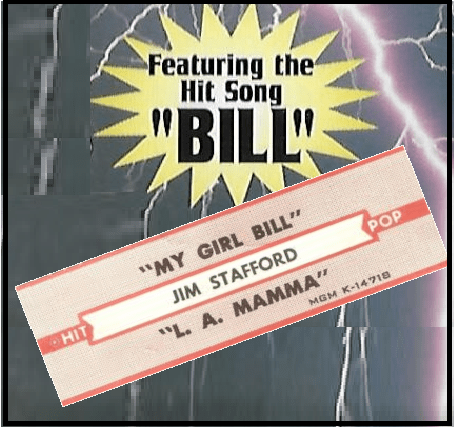

And then there’s “My Girl Bill,” a single that evokes lots of complicated feelings. The only simple thing I can say about it is I don’t consider “My Girl Bill” a novelty song. Almost a quarter-century after Stafford, Southern soul singer Peggy Scott-Adams scored an out-of-left- field Hot 100 hit in March 1997 with another “Bill.” And that, too, brings up a complex reaction. I’d argue that – despite its atypical storyline – it’s also no novelty song.

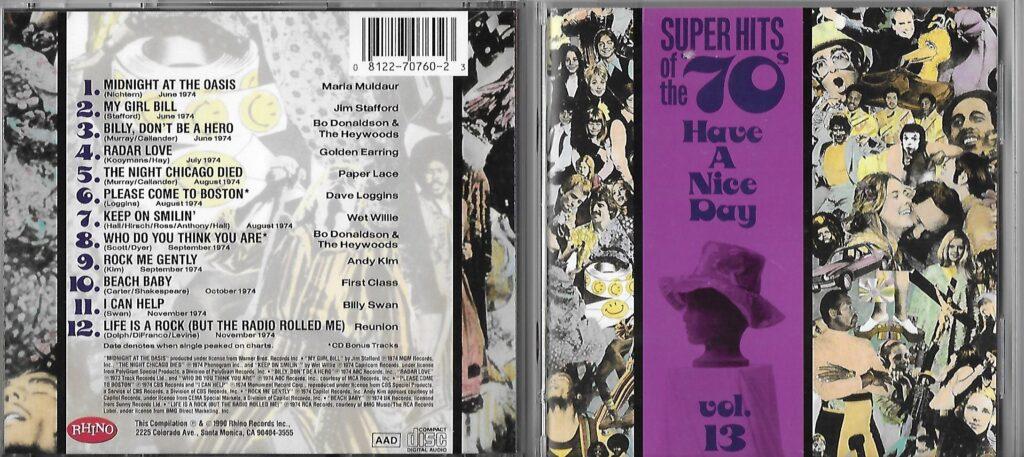

In his album notes for Volume 13 of Rhino’s “Super Hits of the ’70s: Have a Nice Day,” journalist Paul Grein writes, “[T]he gay rights movement was gaining momentum, with thousands of homosexuals coming out of the closet. How do we know all this? From listening to Top 40 radio… Jim Stafford’s sly ‘My Girl Bill’ flirts with the topic… [F]or a while there ‘My Girl Bill’ was shaping up as the ‘Walk on the Wild Side’ of the MOR set.”

I was 10 going on 11 when this song was a hit, and I didn’t really understand it. It also was not the smash on Chicago’s WLS and WCFL that “Spiders and Snakes” was – it did hit No. 8 at both stations but lasted on WLS’ chart all of four weeks (compared with 13 for “Snakes”). I’ve a feeling its subject matter was too much for AM radio to sustain for long, or programmers and audience thought the joke quickly wore thin.

What was the joke? Ostensibly, that Bill wasn’t the narrator’s “girl,” but – SPOILER ALERT! – his rival for the affections of a woman ( “You’re gonna have to find another/’Cause she’s my girl, Bill” ). More interestingly, the real joke is on the listeners, since Stafford’s near-perfect delivery of the first two verses keeps them wondering whether they’re hearing the story of a male couple. (“Near-perfect” because I can hear a smirk in “ William’s hands were shaking …”) It’s not until the final verse that Stafford drops the towel and reveals all – nothing shocking, folks, just a missing comma, that’s all.

As a long-out-and-proud gay man, am I supposed to hate “My Girl Bill”? I don’t know that I subscribe to any theory of identity music-criticism. I can only say I find Stafford’s song a hoot. Not because gay relationships are something to snicker at but because “she doesn’t want to see [Bill’s] face and she wishes [he was] dead.” I also like the thought that casual radio listeners might have engaged in literal or figurative pearl-clutching up through verse three. (I know my dear, departed Aunt Elaine would have been shocked, shocked!)

I will warn those who want to check this out on YouTube: Watch the non-performance version. Stafford’s performance on stage is all the things the record is not – smarmy, winking from the start, almost begging one to ask if Stafford might indeed be wondering, “What would the neighbors think?”

How do a woman compete with a man for another man?

Peggy Scott Adams

Although I was a callow preteen when Stafford scored with his “Bill,” Peggy Scott-Adams’ bluesy lament exploded on adult R&B radio when I was 34, about 5 years into my relationship with my now-husband. You might think a song with lyrics like “My man was just a queen/he was a queen that thought he was a king” would be DoA in my household. Nope. I find it as fascinating a tale of its time as Stafford’s.

American popular culture spent much of the mid- to late ’90s questioning what it meant to come out. A decade and a half after the notorious backlash against Elton John’s Rolling Stone interview, artists from Melissa Etheridge to k.d. lang to Judas Priest’s Rob Halford helped refine the public image of coming out. This was equally true among African-American artists, where decades after the work of James Baldwin and Audre Lorde, novels such as Terry McMillan’s “Waiting to Exhale” and E. Lynn Harris’ “Invisible Life” addressed – primarily, in Harris’ case; tangentially, in McMillan’s – what it meant to be gay and black in an often-hostile American culture.

It’s in this context that Scott-Adams and producer/songwriter Jimmy Lewis tell the tale of a woman who learns in a dramatic way that her husband is in love with his best friend. The tale is first-rate soap opera:

We were at a party, Oh to have a little fun,

But when I looked around my-my man was missing

I walked outside, I couldn’t believe my eyes

He was in Bill’s arms breathing hard and french kissing

I was ready for Mary, Susan, Helen and Jane

When all the time it was Bill who was sleeping with my man

What follows is not just the story of Bill and the narrator’s husband but, as important, the complicated feelings of the narrator, processing her husband’s sexuality while coping with the fact that she was being left for someone else. These feelings are raw: “Bill was a friend, and he was god-uncle to my only son/Now it looks like Uncle Billy wants to be his stepmom.”

Where Stafford’s “Bill” spurred radio attention through calculation and revelation, Scott-Adams’ “Bill” earned its moment in the sun with candor and complexity. It’s easy to write off this song, but also a cop- out, to write off this song as merely camp. Listen to this couplet, and it’s hard not to feel empathy for everyone involved: “ As tears came to my eyes, he says, ‘I’m sorry I hurt you so/I got to pack, Bill is waiting for me, and oh girl, I got to go’ ”

Here’s where a second YouTube warning is essential: The album track – indeed, the only version with which I was familiar – is 5:11. The video on YouTube features a 4-minute-plus version that does real damage to the song, fading out not long after the “queen who thought he was a king” lyric and leaving out a vital exchange between the narrator and her soon-to-be ex (“ If that’s not asking too much, baby, could you tell my son I love him and I’m still his dad” ). The clumsy edit leaves the narrator bitter and the husband feckless, and the song is all the poorer for it.

Apparently, Scott-Adams recorded a sequel, “Life After Bill.” I’ve never heard it and don’t intend to. I suspect it’s what “Dance the Kung Fu” is to “Kung-Fu Fighting” and would rather keep my memory of the original intact.

Quick but complicated windows into the ’70s, the ’90s and what would become the LGBTQ+ community, both songs – neither a novelty – fit the bill.

As someone named Bill, I wasn’t sure how to feel about “My Girl Bill.” I was young enough at the time that I didn’t really get what gayness was, but I knew I got a lot of teasing about it so it must be bad. That changed of course when I ended up at a college whose student body was 62% gay. I got to know gay people and they seemed a lot like, well, everyone else I ever met. It wasn’t so bad after all.

I’d never heard Peggy Scott-Adams’ “Bill” until today. It seems a little overwrought but so are a lot of songs about getting dumped. Still, the story’s twist is one we don’t hear often and it’s treated with respect. We need more of that.

Great read, cst, even though I’m not familiar with either song!

Very interesting. “My Girl Bill” sounds so much like Transformer-era Lou Reed, I wonder if Stafford was intentionally riffing on that sound?

The intent of the song reminds me of Rod McKuen’s album from the late 50’s: Beatsville. This album is a comedic spoof of the Beat generation. Unlike the more openly sardonic parodies, such as Bob McFadden’s “The Beat Generation,” (which is now remembered solely because Richard Hell did his own riff on it), McKuen’s spoken word pieces are a little more humane. There are plenty of silly thoughts and observations, but really it’s not all that different from his more sincere (and unintentionally funny) spoken word from the previous year: Time of Desire. I often can’t tell if the work is ineptly satirical or ineptly sincere, and so the result is some mix of comedic distance and curious admiration.

Perhaps approach reflects ambivalence about their targets of humor, a sort of guarded fascination. But back then, that was certainly better than outright disdain!

I remember the first song, and, yes, some people were shocked. I don’t remember finding it very shocking…or very funny. I wasn’t particularly offended by it, either. But neither did it occur to me to wonder if gay people would be upset. (I’m not at all sure that I knew the word gay at that time. I won’t repeat the words that I knew.) When I occasionally heard it referred to in later years, I cringed. We may not have made the progress that we should have as a society, but we’re a damn sight better than we were then.

I appreciate reading your point of view. Love to you and your husband.