The Hottest Hit On The Planet:

“St. Louis Blues” by Bessie Smith (featuring Louis Armstrong)

Dear gentle reader,

I realize that I write, as Tom Breihan might put it, “long-ass columns.”

But I do value your time. Really, I do.

I don’t wish to waste it.

Time is a valuable commodity. There is simply not enough of it. When dealing with a decade as long ago as 100 years, I can understand if you feel that you only have time to listen to one or two songs. I think you are wrong to feel this way, but I understand.

And so, to save you some time, I have identified the one single record of the 1920s to which you need to listen. One record to stand in for all the rest. The one record that encapsulates so very much of what was happening, music-wise, in the 1920s. A record located at the junction between three of the biggest musical icons of the decade:

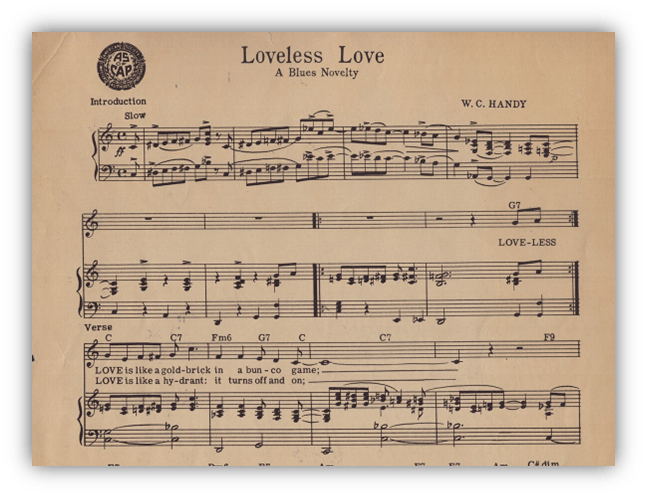

- W.C. Handy, who wrote the song, and claimed to be The Father Of The Blues.

- Bessie Smith, who sang the song, who was crowned the Empress Of The Blues, for her work in living her life as though it were a blues song.

- And special guest: Louis Armstrong, the loudest cornet player in the world of jazz, although there wasn’t a great deal of difference between jazz and blues at the time anyway.

Not only was “St Louis Blues” located at the crossroads between these three musical legends, but it was set – and named after – a town that served as the crossroads of America.

St. Louis was located right smack-bang in the middle of the United States.

Folks from The West going east, from The East going west, from The North going south or The South going north, all had to pass through St Louis.

When folk arrived in St. Louis after a long arduous journey by train or covered-wagon, they needed a place to party. Many of those parties ended up at The Castle.

The Castle was famous across the land, at least amongst wealthy white men who were the only ones admitted.

It was famous for having a mirror for a floor, an interior design choice made all the more salacious by the girls not wearing any underwear.

The Castle was also famous for Mama Lou: possessor of a filthy mouth with which she would both sing and insult the patrons, was almost always described as “a gnarly voodoo princess”, and may also have a been a musical genius. Minstrel-show song-writers from across the land would visit The Castle to steal her songs, although they’d usually have to clean the lyrics up a bit first. Curiously enough, Bessie Smith would record one of those songs, decades later.

St Louis was a famously tough town. This was, after all, the St Louis of Stagger Lee, a man who – so legend and countless blues songs has it – shot a man for stealing his hat. This was the St. Louis people thought about when they thought about St Louis. Not “Meet Me In St Louis, Louis”, but “St. Louis Blues.”

Another reason for selecting ‘St. Louis Blues” as The One 1920s Record You Need To Know?

“St. Louis Blues” was POPULAR!

“St Louis Blues” was quite possibly the most popular song of the 1920s.

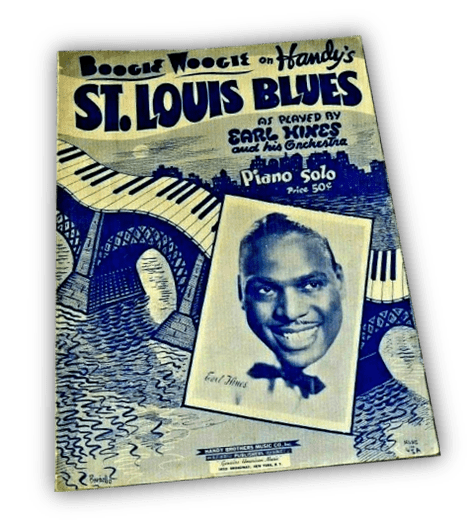

Or at least in the 1920s; since it had been written, and first recorded, in the 1910s, based on a chance meeting in the 1890s. By 1925, it had become a standard. Recorded by seemingly everyone. But no-one had recorded a version that could really be considered “definitive.” Nobody had even come close.

The first recorded version – in 1915 – was by Charles Prince’s Band, the house band for Columbia Records.

By the time Bessie got her hands on it, “St Louis Blues” had been recorded by the Wadsworth Novelty Dance Orchestra, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band… it had crossed the Atlantic where it was recorded by London’s Ciro’s Club Coon Orchestra. There was a Hawaiian ukelele version by Frank Ferera. White flapper favourite Marion Harris had a huge pop hit with it…

…as did the even-whiter, decidedly WASP-ish Al Bernhard…

Most of these renditions were instrumentals, most were inappropriately perky, and precisely none of them sounded as though they had the blues.

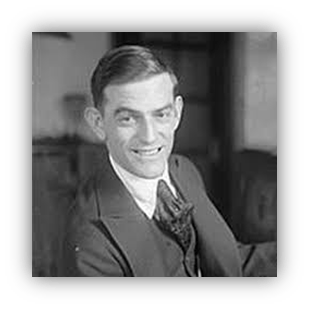

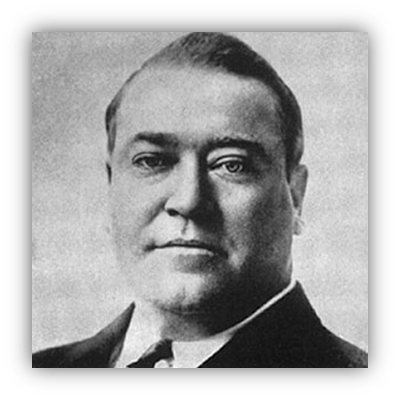

You might expect that W.C. Handy, the composer of “St Louis Blues” – would feel disappointed by the perkiness of these version, but possibly not. After all, W.C. recorded a version himself, in 1923, and it may be the perkiest version of all!

William Christopher Handy was – like all great American heroes – born in a log cabin. In Alabama, where his father was a local pastor. It will not surprise you to learn that young W.C. once brought home a guitar only to have it banned because it was sinful. When your father is a pastor, you’ve got to expect that sort of thing.

W.C. finally left home to spend his youth travelling across America, sometimes employed in travelling bands, sometimes not.

Finding himself in Alabama, Memphis… and the Mississippi Delta where W.C. bumped into the most influential musician of the 20th century, the name and identity of whom will never be known for sure.

Some believe it was Henry.

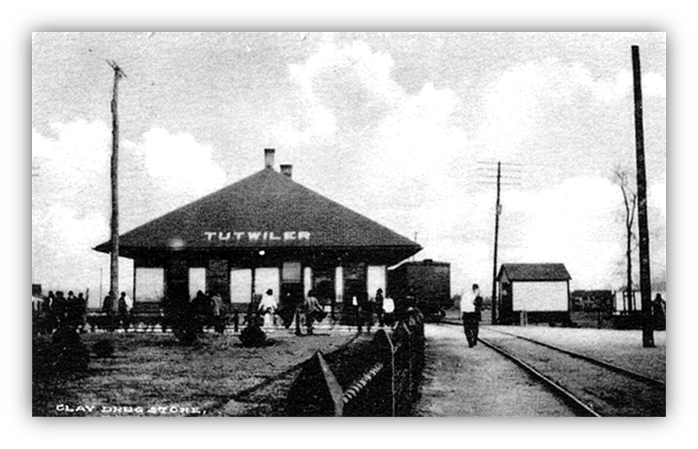

The man-with-no-name-but-possibly-Henry was waiting for the train one day, in a tiny little settlement called Tutwiler.

“Henry” – described by W.C. as a “lean, loose-jointed Negro” – was playing the guitar with a knife – using the knife blade a bit like a slide guitar, even though slide guitar was yet to be invented – moaning some nonsense about “goin’ where the Southern crosses the Dog”. These weren’t deep lyrics or anything. “Henry” was just mumbling about his plans for the day.

It just so happened that W.C. was waiting for the same train as “Henry”, and he thought it was the weirdest music he ever heard.

Years later, when W.C. started writing songs, he would base them on this memory.

At about the same time, W.C. also found himself one night in St Louis, where he met a woman. A woman who hated to see the evening sun go down. A woman who was tearing herself apart because – to quote W.C. quoting her – “My man’s got a heart like a rock cast in de sea.” A woman whose man has been stolen by “a St. Louis woman with her diamond ring.”

Now, I may be misreading what W.C. is suggesting here.

But given the reputation of St Louis at the time I’d say there’s a high likelihood that this woman’s man has been stolen by a high-end prostitute.

Singing a forlorn break-up song about being dumped for a high-end prostitute was very much in Bessie Smith’s wheelhouse.

Bessie had been brought up tough. In Blue Goose Hollow, Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Her father died when Bessie was a baby. Her mother died when Bessie was eight.

Bessie spent much of her childhood dancing and singing for money on the streets of Chattanooga with her brother, Clarence. By her teenage years she’d joined the carnival circuit.

Bessie Smith was a mess – an exhilarating mess. And as she got more and more famous, her life and its scandals would only get worse. Some people criticized Bessie’s life choice, but for them, Bessie had an answer record: “T’ain’t Nobody’s Biz-Ness if I Do”, quite possibly the first pop record title to feature intentionally bad spelling! (“T’ain’t Nobody’s Biz-Ness if I Do” is a 10.)

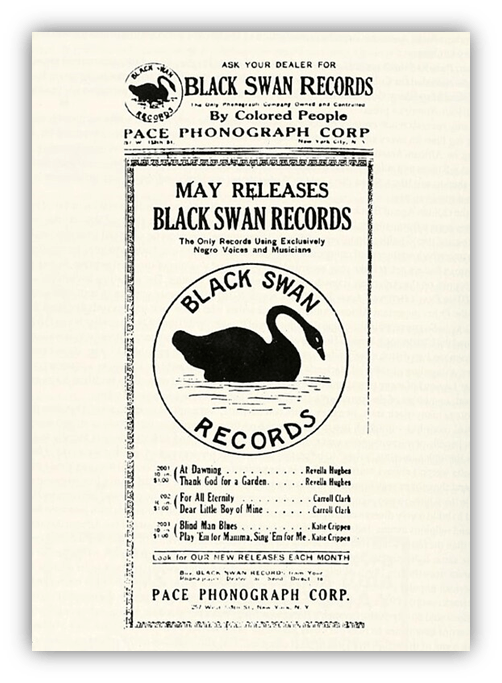

Recording the definitive version of “St. Louis Blues” wasn’t the first time that Bessie Smith had had a connection with W.C. Handy, or at least W.C.’s circle of friends: for a couple of years earlier Bessie had auditioned for Black Swan Records.

Black Swan was a record company with a mission: a record company whose entire business strategy was based on a political ideology. It was run by Harry Pace, who had previously run a hugely successful sheet music company with W.C. Handy, before deciding that records were the future. W.C. disagreed, so he sat this one out. Harry Pace had also previously been a student of Black civil rights activist and thought leader W.E.B. DuBois.

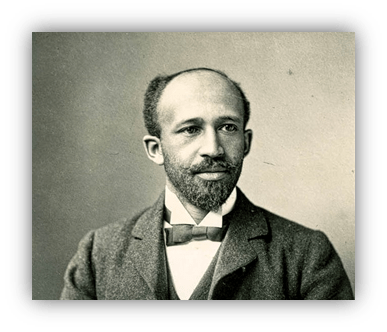

W.E.B. had come up a theory called “The Talented Tenth.”

It was based on the concept that the Black community should concentrate their efforts on supporting their 10% most talented members, so that, when the rest of the Black community – the 90% – saw the 10%’s success, they’d want to be successful too. Harry was hugely impressed by this theory, and decades later, as the owner of Black Swan Records, he grabbed at the chance to put it into practice.

But:

Black Swan Records were torn. Their own personal tastes – informed by the whole “Talented Tenth” theory – were extremely middle class.

They signed an opera singer. They signed a handful of other celebrated classical musicians. They didn’t sign Bessie Smith.

They didn’t sign Bessie Smith because she spat on the floor. In the middle of her audition. In the middle of her song. And then kept on singing like that was a perfectly natural and reasonable thing to do. This was not the kind of example that Black Swan wanted to set for the Black community.

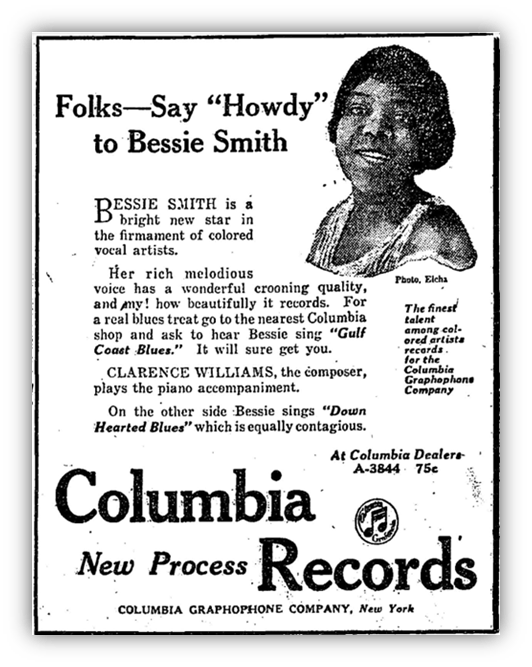

Which is why Bessie ended up going with Columbia Records.

Columbia were either the second or third biggest record company in America at the time and had a hell of a lot more money to spend on marketing than Black Swan could even imagine.

And market her they did. Claiming they had discovered “a new star in the Constellation of Ethiopia… we invite you to pick up your telescope and gaze at Bessie Smith.” And gaze they did. And also – far more importantly – they listened. They didn’t have charts back then, but if they did, Bessie’s first record, “Downhearted Blues”, would have been a Number One!

Bessie Smith singing a W.C. Handy classic would have been more than enough to earn “St Louis Blues” a place in the blues cannon. But wait… what if we added another Louis to “St. Louis Blues”? What if we added a blast of Louis Armstrong?

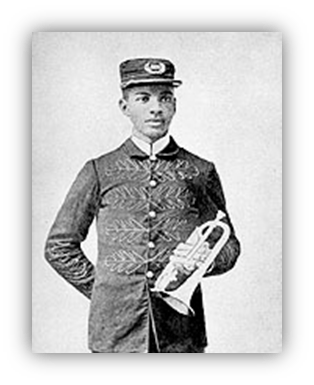

Louis Armstrong probably wasn’t chosen for the “St. Louis Blues” session because of his name. Otherwise, they would have put his name on the label. Louis Armstrong simply wasn’t famous enough yet.

He was something of a legend in New Orleans and Chicago and was building a reputation in New York.

He’d gotten a gig with Fletcher Henderson, probably the biggest Black band leader of the 1920s… but you couldn’t really call him famous, yet.

Louis Armstrong had made the move from his birthplace in New Orleans up to Chicago a few years earlier, to play with King Oliver and His Creole Jazz Band. King Oliver had recently got a regular gig playing the Lincoln Garden in Chicago, the largest ballroom on the South Side, with a dancefloor large enough for two thousand feet; so he figured his band needed a little more horn-power.

King Oliver and Louis had previously played on steamboats together, playing to tourists cruising up and down the Mississippi, so he knew exactly who to call.

By 1925, Louis was in New York playing with Fletcher Henderson’s band, trying to convince Fletcher to let him sing. Fletcher, quite understandably really, thought that was a ridiculous idea and never let Louis anywhere near a microphone.

Even when playing the cornet, Louis was made to stand at the back of the studio, because he was too darn loud!

Some say Louis was too darn loud on “St. Louis Blues” itself. There are some who think that Louis hogged the limelight, rudely interrupting Bessie trying to sing the song. One person holding such views was Bessie herself.

On “St Louis Blues”, Bessie founds herself in the unfamiliar situation of not being the centre of attention. Louis is drowning her out.

Bessie seems uncomfortably aware of this, and growls as loud as she can to try and reassert herself as the alpha, not a problem she usually has to deal with. Bessie has the “I’m Being Overshadowed By Louis Blues.”

I like to think then – based on no evidence but my imagination – that the other record Bessie and Louis made together, was Bessie’s attempt at a rematch. Why else would the record be titled “I Aint Gonna Play No Second Fiddle”? Bessie makes certain that she wins this time; Louis has certainly been sent to the back of the studio for being too loud.

And this was with a cornet, aka a baby trumpet. Louis would soon adopt a proper trumpet. Imagine how loud he would be now?

Despite possibly being distracted by Louis, Bessie sings “St Louis Blues” the way it’s supposed to be sung. The way you might sing it if your man had been stolen by woman with store-bought hair. But better, because, this is Bessie f*ckin’ Smith!

“St. Louis Blues” may not be the best record of the 1920s, but it captures the sadness of that poor woman in St. Louis, like no other version ever has, and it’s an 8.

Meanwhile, In Jazz Land:

“Vine Street Blues” by Bennie Moten’s Kansas City Orchestra

Not too far away from St. Louis, just at the other side of Missouri:

They were dancing in Kansas City.

Kansas City was about the only place in America that you could dance, or at least legally dance with a couple of beers under your belt the way it ought to be done.

This was largely due to the influence of the Tom Pendergast:

A behind-the-scenes-string-puller-par-excellence of the Jackson County Democratic Party – specifically the “goats” faction, so called because so many of their Irish supporters kept goats in their backyard – and quite possibly the most corrupt political player in America.

Under Tom’s influence, Kansas City waged a one-city war against the forces of Prohibition.

He achieved this by appointing an ex-criminal to be in charge of the Kansas City police force, who in turn made the managerial decision of giving the officers low salaries so that they’d be forced to accept bribes.

With Kansas City thus declared open for business, the city became a magnet for every second blues and jazz musician in the mid-West (the rest of them went to Chicago instead).

Jazz bars flourished, along 12th Street, and particularly around 18th and Vine, which was fast becoming a sort of Harlem of The West:

Complete with Black-owned businesses – hotels, theatres, cinemas, a baseball team, as well as other less entertaining but perhaps more essential businesses.

Being the only place in America where you could get a drink – without being sneaky about it – certainly lit some sort of fuse. There were clubs in Kansas City that never closed! The cleaners came in early in the morning and cleaned around whatever patrons were still there. This seems to have influenced how the music was playing.

Jamming sessions in Kansas City saloons could last for hours and hours, usually playing the same riff over and over again, over the top of a stompin’ beat.

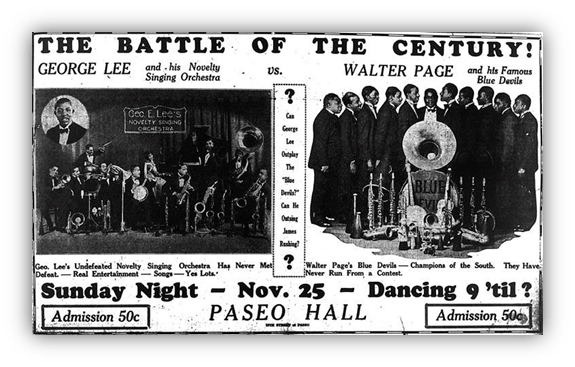

Bennie grew up in the 18th and Vine neighborhood and judging his song titles he was extremely proud of these roots. In addition to “Vine Street Blues”, there was “18th StreetStrut.” (Mind you he also recorded a “Kater Street Rag”, which I can’t find on a Kansas City map, so is presumedly about the street in Philadelphia… also “South” which is frustratingly vague:)

In addition to playing a riff, and grinding it into the ground, the way Kansas City bands played the groove was also unique, since different rhymical instruments would play on different beats. Some would play on the first and third beat. Some on the second and fourth beat. Rockin’ back and forth like this, made Bennie’s beat seem bigger. And that’s about the closest thing to a discussion of music theory as you are ever going to get from me.

“Vine Street Blues” is rather less raucous than that description might have you expect. Consider it Ben’s crossover ballad. For something closer to what they were probably playing on Vine Street, here’s Bennie’s debut single from 1923: “Elephant Wobble.”

Bennie Moten may have been the leader of the Kansas City Orchestra, but he wasn’t necessarily its musical genius. Bennie’s cleverest move was to pay his band well – and then get out of the way so that they could jam. Sometimes he wouldn’t even be playing in the band, he’d be out on the floor, making sure the business side of things was going smoothly.

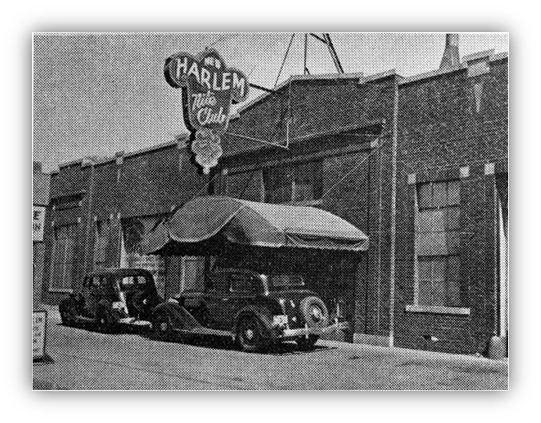

The business side of things included managing his own dancehall, The Paseo Hall, in which more than 2,000 dancers could squeeze.

Paying your band well turns out to be a good way of attracting talent. So Bennie soon got:

- Sam Tall on banjo – who instead of plunk-plonking like most banjo-players, would rhythmically scratch

- Woody Walder on clarinet – which he made sound like a kazoo

- And eventually Count Basie on piano, a guy who definitely knew how to swing.

But Count Basie wasn’t in Bennie Moten’s band yet; he wasn’t even in Kansas City. He was still in New York. When Count finally joined the band in 1929 he wrote them a “New Vine Street Blues”, and it’s even slower than the original. Man, it’s stylish, though!

Bennie doesn’t appear to have written any lyrics for “Vine Street Blues”, so it’s difficult to know if we are supposed to be feeling happy or sad. There’s certainly a melancholic strain to it, but they also seem to be having a lot of fun. I mean, they’re on Vine Street, having fun is legal; how could they not?

“Vine Street Blues” is an 8.

Meanwhile, in Old Timey Land:

“Keep My Skillet Good And Greasy” by Uncle Dave Macon

Skipping back east, but not too far, to Nashville, Tennessee:

On November 28th 1925, a new radio show was broadcast on WSM, a radio station owned by the most unglamorous corporation imaginable, the National Life and Accident Insurance Company. The new radio show was titled the WSM Barn Dance. Within a couple of years it would be given a new name: The Grand Ole Opry.

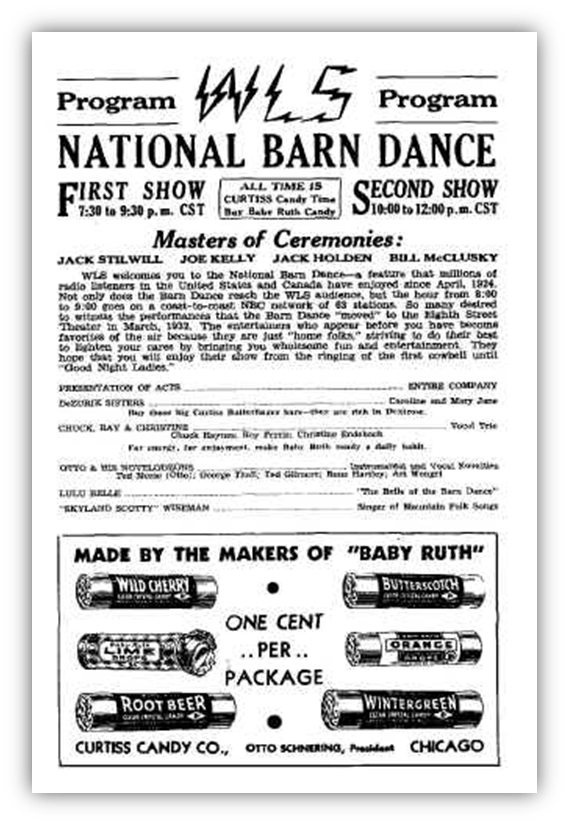

Presumedly, they changed the name to The Grand Ole Opry to avoid confusion with a similar show broadcasting out of Chicago: the WLS National Barn Dance.

Audiences could be forgiven for being confused, given that the man who presented the WSM Barn Dance had previously presented the WLS National Barn Dance (I’m getting confused just typing this.)

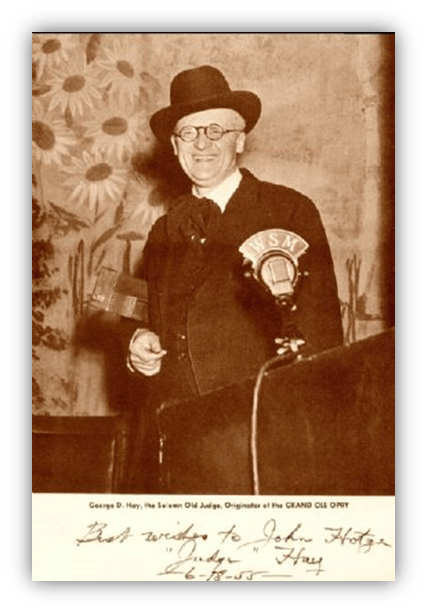

A man who, even though he had only turned 30 a week before, went by the stage name, “The Solemn Old Judge:

A man with a personal motto which he believed to be the key to his radio presenting success: “Never Fail To Broadcast A Smile.”

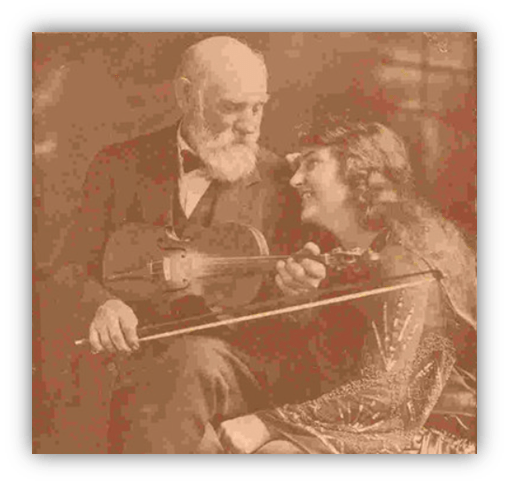

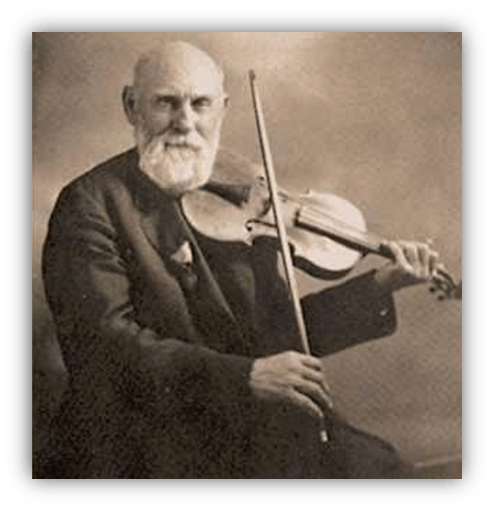

The first act to be broadcast on the WSM Barn Dance was an 82-year-old fiddler with an outstandingly bushy beard, Uncle Jimmy Thompson, and his niece who he disturbingly referred to as “Sweetmeats.”

A worthy claimant to the title of The Greatest Fiddler Alive, Uncle Jimmy had entered the fiddlin’ scene when he became too old to farm.

Uncle Jimmy’s qualifications for being The Greatest Fiddler Alive including his winning of an 8-day fiddlin’ competition, and the fact that he knew who to play 375 songs from memory. Sometimes he exaggerated and said he knew thousands. Regardless of the exact number, it was a handy skill to possess, particularly given that on the show, Uncle Jimmy took requests from listeners.

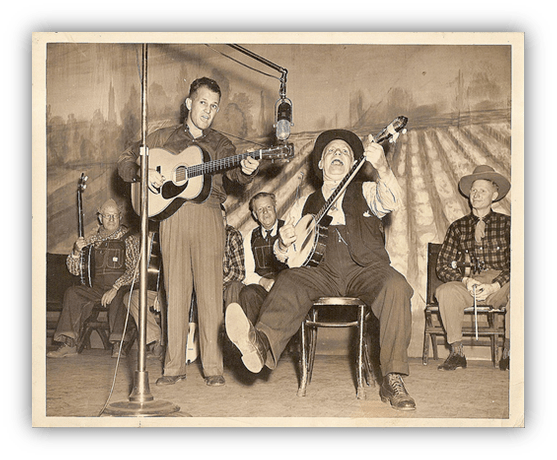

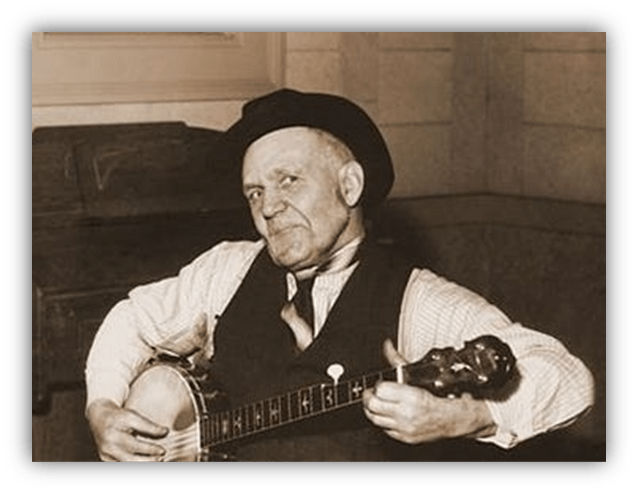

Uncle Jimmy was not the only uncle on WSM Barn Dance. There was also Uncle Dave Macon.

Uncle Dave wasn’t quite as old as Uncle Jimmy, but he was old enough that it seems compulsory to refer to his facial hair as “whiskers.”

“From his farm every fall”, the Radio Digest explained, “goes Uncle Dave with three banjos tucked under his arm… the veritable wandering minstrel… he radiates sunshine and goodwill.”

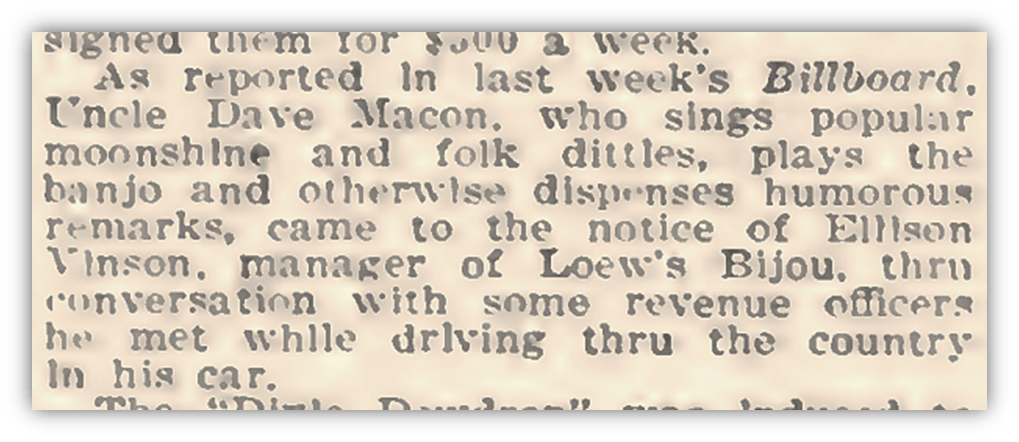

Just in case such prose didn’t highlight Uncle Dave’s hillbilly heritage enough, Billboard seems to have decided to describe his genre as “moonshine and folk:”

A term that sadly did not catch on. So we’ll just refer to it as country music.

Uncle Dave had already run a successful mule-freight company: singing and plunking his banjo for passengers and passersby as he did so – a company which was gradually becoming less successful as cars and trucks began to do the same job, and with far less stubbornness. By the time Uncle Dave found himself on the Barn Dance he was already a big name in hillbilly-flavoured vaudeville.

In Birmingham, Alabama, his show – with a buck dancer named Dancing Bob providing percussion, clomping out the rhythm with the clogs on his feet – broke records.

Sad to report however that Dancing Bob does not make an appearance on “Keep My Skillet Good And Greasy.”

Uncle Dave had also made a whole bunch of records, many of which reflected a preoccupation with food, such as “She Was Always Chewing Gum” and “Bile Dem Cabbage Down:”

The latter of which was an old-time square-dancing standard, probably of Black origin, which had been around for so long it had gathered a whole bunch of alternate titles: “Bake Them Hoecakes Brown”, “Possum Pie”, “Carve That Possum”, and somewhat more appealingly “Rocking My Sugar Lump.”

Uncle Dave performed “Bile Dem Cabbage Down”, almost as a comedy sketch, stopping every now and then to tell a “humorous” story, including one about a dog being hung for killing his chickens.

The stealing of chickens seems to have been something of a preoccupation for Uncle Dave. A few years later he’d also record minstrel-show favourite “Bake Dat Chicken Pie”, which includes instructions on how exactly chicken-stealing is accomplished: you knock ‘em off with a pole, slap ‘em like a goat, if they holler loudly, you stuff it under your coat.

Chicken stealing also plays a key role in “Keep My Skillet Good And Greasy.” Uncle Dave has chickens in his sack and bloodhounds on his track. He’d also “stoled a ham of meat.” Given that he appears to only have enough money to “buy a sack of flour” which “gwine cook it every hour”, you can’t blame him for wanting a bit of variety in his diet.

Uncle Dave is also laying around the shanty, and buying a jug of brandy for Mandy, so that she’ll be good and drunk and boozy. That verse about Mandy and the brandy makes it sound as though “Keep My Skillet Good And Greasy” is some hillbilly euphemism, but as best as I can tell it’s just about frying stolen goods.

Uncle Dave is a good-for-nothin’ lay about and he’s not afraid to sing about it.

Uncle Dave had learnt “Keep My Skillet Good And Greasy” from “an old colored man,” who worked in “a grist mill”, presumedly during Unkle Dave’s mule-freight period. It was certainly a song that was going around. Being an academic travelling around America, collecting old Black and hillbilly folk songs was a popular occupation at the time, and “Keep My Skillet Good And Greasy” – or at least a bunch of very similar songs – was uncovered repeatedly.

In Tennessee, where they called it “Chicken On My Back” and in Mississippi, were it appeared to be called “I’m Gonna Make It To My Shanty Ef I Kin.” In that version they appear to be collecting enough ingredients to cook a responsible and nutritionally balanced meal: chicken, lard, greens, even a bumblebee for some reason!

So that’s how country – sorry, “moonshine and folk” – music began. Old guys with banjos and fiddles singing about stealing chickens.

At least until Henry Ford decided that he wanted to spend a large chunk of his fortune promoting “old timers” music as part of his campaign to destroy the jazz he felt was eroding the moral fabric of the nation –

… but that’s another story…

“Keep My Skillet Good And Greasy” is a 7.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Looks like I forgot to include the link to “St. Louis Blues”… let’s remedy that shall we!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cwRbsULaQIo

Your writeup perfectly captures the essence of this recording, DJ Professor Dan! Can’t believe that it’s the first time I’ve heard this song.

Nice work, DJPD. Love the deep dive into “St. Louis Blues.” It sure was a perfect storm.

Prohibition and Kansas City’s heyday are long since over, aside from their football team, but I still need to do something bad for me. Like eat BBQ.

I’ve never heard of Uncle Dave or his backstory, but I’ve heard “Skillet” and it’s good and greasy.

Hey! Century old songs! I do my big band/swing radio show once a week, and at 9pm ET I always feature what the #1 song was 100 years ago (according to Joel Whitburn, and I always mention that his charts were kinda made up). I played Marion Harris’ version of “St. Louis Blues” a month or so ago. I always like that song, but I’ve got to admit, I’m way used to peppier versions of the song. Bessie has a very slow blues style. Maybe not my favorite, but very authentic sounding.