The Hottest Hit On The Planet:

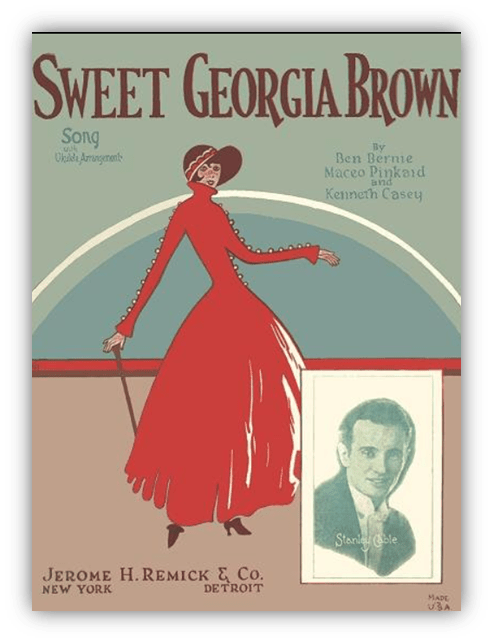

“Sweet Georgia Brown” by Ben Bernie

Here’s a cute little story.

Dr. George Thaddeus Brown was a state politician in Georgia – it was kind of the family business.

His uncle had been the governor, and his wife, Avis, had just given birth to a baby daughter. And they named their new daughter, Georgia.

Given the fashion at the time for naming your children after yourself, you may have thought that George had named his daughter Georgia for that very reason. George already had one son called Georgia from a previous marriage – Avis was No.2 – so he was clearly into that sort of thing.

But that was not the reason.

George and Avis didn’t have much choice in what to call their daughter.

That decision had been taken out of their hands by the Georgian General Assembly, who had passed a motion and made a declaration stating that Georgia must be her name.

As the local newspaper The Atlanta Constitution put it, “the resolution naming the baby “Georgia” was passed by both houses and formally enrolled as an act of state.”

Or, as the song would put it a decade or so later, “Georgia claimed her, and Georgia named her.”

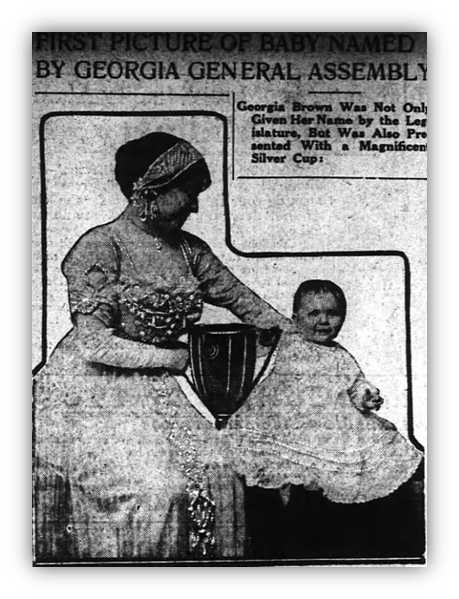

Every member of the legislature automatically became Georgia’s godfather. They also presented her with a great big silver cup!

This apparently was the most pressing issue in Georgian politics in 1911. It was, at the very least, a big news story. Almost as big as the cup!

Given that every member of the legislature was now her godfather, it would be rude of Georgia not to invite them all to her first birthday, and so she did. Everyone working in building was invited. It was an ice-cream party!

The invitation was once again read out to the General Assembly, and – once again – passed both houses unanimously.

Why can’t politics always be so bipartisan?

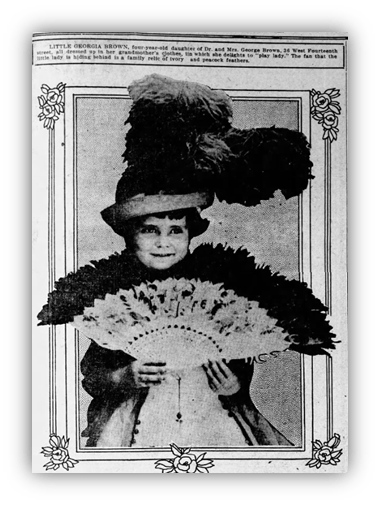

Georgia continued to be a bit of a celebrity in The Goober State for a couple of years:

Years past, Georgia grew up, and she appears to have stopped appearing in newspapers quite so often.

Fame, it’s a fickle beast. But then her father, whilst on a business trip to New York, got into a conversation with zany band leader, Ben Bernie.

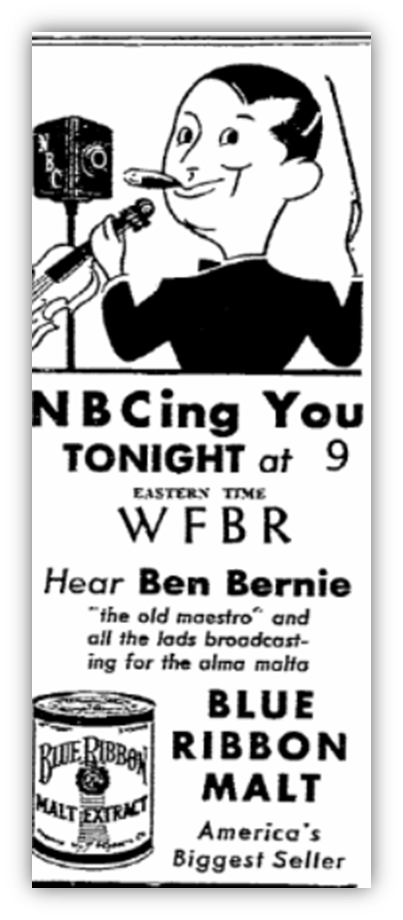

Ben Bernie was billed as “The Old Maestro.” I presume that billing was at least partially ironic.

I presume that billing was at least partially ironic. Although Ben did play the violin, and although he did lead a band – Ben Bernie And The Lads – he didn’t seem to play it all that much, preferring instead to enthusiastically conduct his band with the violin bow.

Every member of The Lads, Ben liked to boast, was a college man. Some of them had studied to be doctors- one had dreams of becoming an explorer – but they had all discovered playing in Ben Bernie’s band to be a far more lucrative proposition.

Even more than he liked to boast about the academic qualifications of his musicians, Ben Bernie liked to crack jokes. Cracking jokes was probably his primary talent.

Before he was known as “The Old Maestro” he’d been billed as “The Jesting Master Of Dance Music.”

Variety once counted “24 genuine laughs” in a concert that only contained seven songs. So about three and a half “genuine laughs” per song. Not bad.

Ben Bernie had a lot of jokes.

Decades later, his brother, who was also his manager, would attempt to sell Bernie’s “gag file” of 32,000 jokes, typed out over 2,700 pages, across four volumes, cross referenced according to 195 major joke categories.

The jokes included, under the category “chorus girl.”

Man: “Have you ever had any stage experience?”

Girl: “I once had my leg in a cast.”

That joke wasn’t a one off. All the jokes were of the same low quality.

It will not surprise you to learn, that prior to his career as a violin-wielding band leader, Ben had starred on vaudeville. It will also not surprise you to learn that it took decades for Ben’s brother to finally find anyone interested in buying the “gag file.” Comedy, it appears, had moved on.

So, Ben and Dr Brown started talking, and the doctor started telling Ben about his daughter and her whole being named by the Georgian legislature story. So Ben wrote a song about her. Not that the subject matter is obvious from Ben’s own version, which is a snazzy jazzy instrumental, and thus has no words.

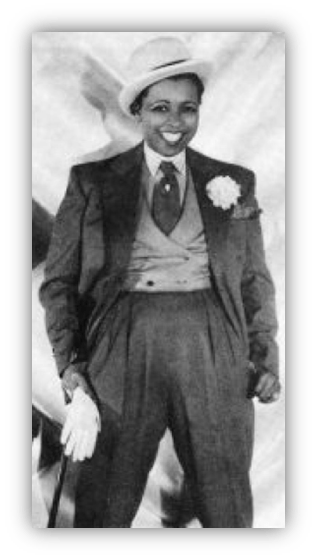

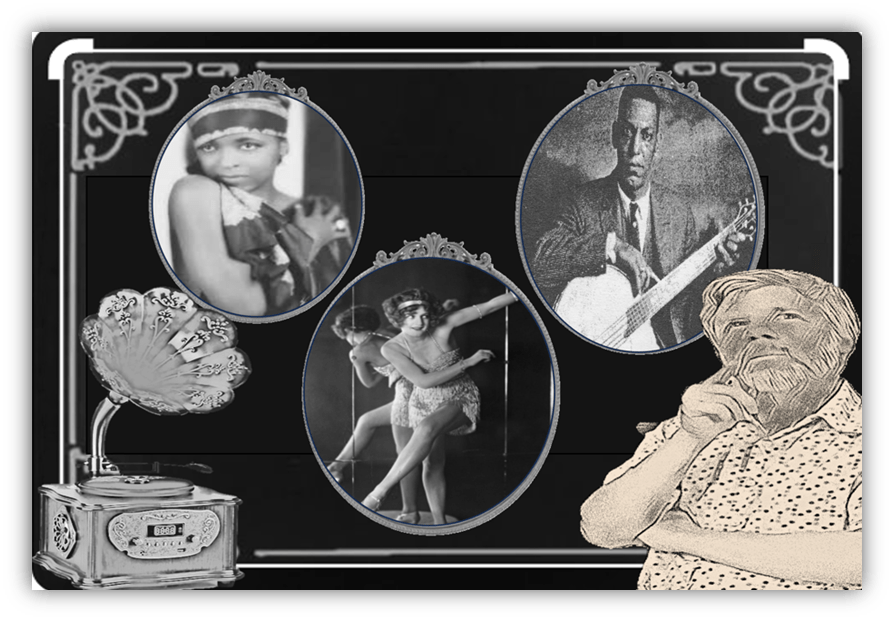

Good thing then that we have Ethel Waters.

Not just because she gave us a version with words in it, but just in general: Ethel Waters was a good thing.

Ethel Waters had been the biggest star on Black Swan Records, the first Black-owned record company.

At least until they went broke in 1923. By 1925, Ethel was the star of the Plantation Revue.

Also the Plantation Club.

And Plantation Days.

I’m not entirely convinced that these are not just all the same show.

There was a lot of this sort of thing going around at the time. Every “Plantation” themed production complete with convincing river scenery, steamboats, log cabins, cotton fields…

Naturally this meant that Ethel would end up singing a lot of southern state themed songs: “Dinah, nothing could be finer, in the state of Carolina” for example… but we’ll get to that one in a few months’ time.

So, “Sweet Georgia Brown” was very much up Ethel’s alley.

Not only because it was set in the South, but because Ethel was a member of the Harlem queer community, occasionally going out in drag.

Ethel seems genuinely smitten with “Sweet Georgia Brown”, a girl so hot that “fellas she can’t get, are fellas she ain’t met”, which you have to admit, is quite the charming rhyme.

“Sweet Georgia Brown” no longer sounds as though it was written about a baby named by the Georgia legislature, does it?

Along the line, Ben’s vision appears to have been lost… and that’s probably because Ben wasn’t the only writer of the song.

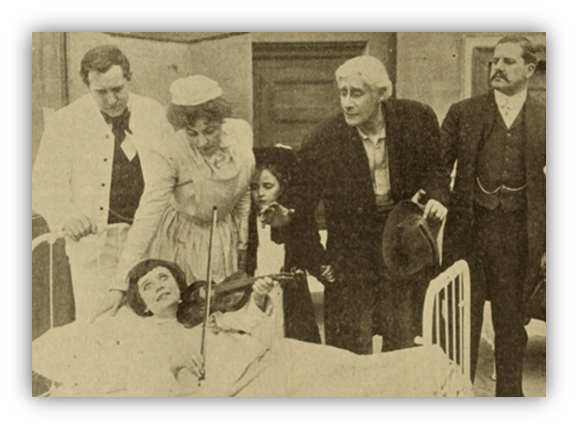

There was Kenneth Casey, a recovering child silent movie star, now a one-hit lyric writer wonder.

Highlights of Kenneth’s silent-movie career had included such challenging roles as “young boy” and “one of the sons”, whilst also demonstrating the early musical ability to play a violin.

Whilst lying in bed at the age of 11.

The music was by Maceo Pinkard:

A bit of a mover-and-shaker on a bunch of Black productions on Broadway at the time. He’d write another major hit the next year.

What did Ben do exactly, then? Did he just come up with the concept, and the “Georgia claimed her, Georgia named her” line, and let Kenneth and Maceo write whatever they liked? It certainly seems like it.

For Kenneth appears to have taken some poetic liberty with his lyrics:

Deciding that, since Georgia’s name was Brown, she ought to be brown herself, and furthermore, that she ought to be a prostitute.

That at least, is the conclusion that many have reached, largely based on the second verse, a verse that the Ethel recording skips in favour of a blistering cornet solo…

“Brown skin gals you’ll get the blues

Brown skin pals you’ll surely lose

And there’s but one excuse

Now I’ve told you who she was

And I’ve told you what she does”

Well, you haven’t really told us what she does. I’d even go as far as saying you’re being frustratingly vague. But the prostitute theory, if a bit of a stretch… it’s not implausible. I’m curious about the creative process that led Kenneth to take that leap from the original premise about the political process, to one of prostitution.

How did “sweet” Georgia Brown herself feel about having such an inescapable song written about her?

Sure, it might’ve been flattering at first, but it wouldn’t be long before it became embarrassing. After all, Georgia was a teenager now; everything was embarrassing! There must’ve been years, decades even, when every time she went out in public, or every time she entered a room, some joker would think it a lark to start up the band to the tune of “Sweet Georgia Brown.” It would have followed her everywhere!

Maybe that’s why she got married at the age of 19 and headed off with her husband to Cuba? Or not. It’s said that she thought the song a “cute, fun thing.”

You know what? She was right!

Both Ben Bernie and Ethel Waters’ versions of “Sweet Georgia Brown” are 8s.

Meanwhile, in Charleston Land…

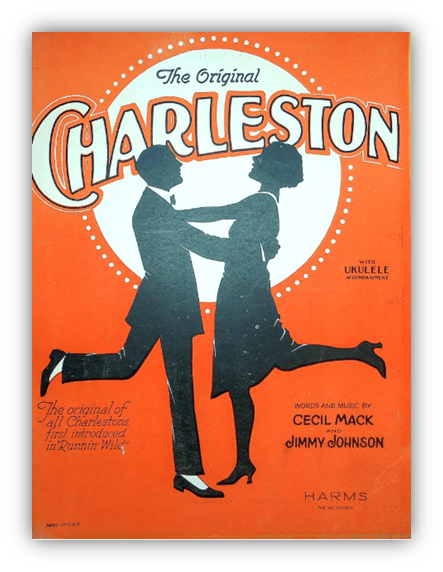

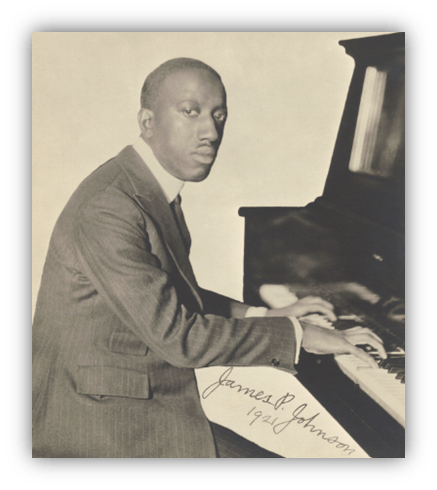

It’s “Charleston” by James P. Johnson

James P Johnson had the reputation for being The Greatest Stride Piano Player In Harlem.

Which basically meant the Greatest Stride Piano Player In New York. Which basically meant the Greatest Stride Piano Player Alive!

James P achieved this reputation over a lifetime of cutting contests at rent parties all over Harlem and Hell’s Kitchen, often against Willie “The Lion” Smith, his closest competition.

But James P had the edge over Willie. James P had a not-so-secret weapon.

James P had composed a piece of music so complicated, so impossible to play, that anyone who wanted to be taken seriously on the stride-piano scene was required to learn it. That piece was “Carolina Shout.”

Aspiring stride-pianists would buy James P’s piano roll of “Carolina Shout”, play it on their pianolas, and slow it down, learning how to play the darn thing by placing their fingers on the depressed keys, gradually speeding it up once they got the hang of it.

James P had composed “Carolina Shout” a couple of years earlier when playing at the Jungle Casino.

Now, the Jungle Casino was not a casino. It was a dancehall, in a basement.

It wasn’t even officially called the Jungle Casino. It was called Drake’s Dancing Class. But people called it Jungle Casino because was located right in the middle of a neighbourhood known as The Jungle:

(actual name: San Juan Hill), a neighbourhood or so north of Hell’s Kitchen and almost as rough.

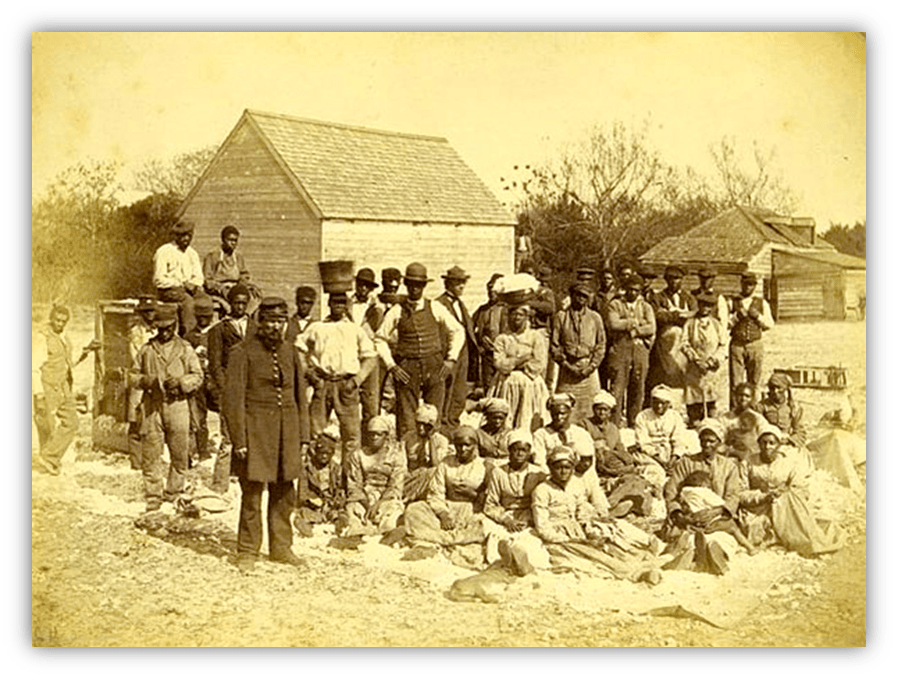

James P called his complex composition “Carolina Shout” because a large proportion of the patrons at Jungle Casino were from Carolina.

More specifically, South Carolina. Even more specifically the swamps of South Carolina, swamps that were virtually impossible to get to, and even more impossible to get off of. Swamps where the inhabitants had little contact with the outside world.

People called them The Gullah.

When the Gullah did finally get off the islands, it was to work on Atlantic shipping lines, and those Atlantic shipping lines went straight to New York. And when they got to New York, the Gullah went straight to the Jungle Casino to hear James P Johnson play.

And there, the Gullah danced. In a manner that Willie “The Lion” Smith described as “get-in-the-alley, real lowdown.” “Carolina Shout” was James P’s attempt at making “get-in-the-alley, real lowdown” music. So, was “The Charleston.”

He seemed to do a good job. The Gullahs seemed to dig it, anyway.

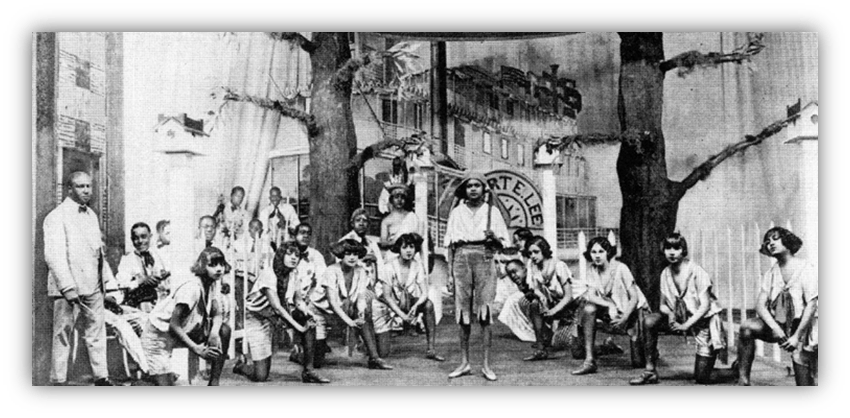

Once James P had transcribed what he was playing – and once a pit orchestra had managed to get their heads and hands around how to play it – “The Charleston” ended up in a Black Broadway show titled Runnin’ Wild, where it also introduced a new dance – a dance based on the “get-in-the-alley, real lowdown” moves of The Gullah at the Jungle Casino – with lyrics added to instruct you what to do.

Or not instruct you what to do, as the case may be. Because although we are informed that The Charleston is easy to do, even if you have previously failed at both the foxtrot and the two-step, the song itself features an appalling lack of dance instructions. Some dance it, we are told, some prance it. You can shuffle it. Every step you do, leads to something new. These are not especially useful directions. Maybe that’s why virtually every recording of the song – including the first one, by Arthur Gibbs, who had also written the title song for Runnin’ Wild – has been an instrumental.

Arthur recorded “The Charleston” late in 1923, and it became a huge hit. One of those probably-would-have-gone-to-Number-One-if-they-had-charts-back-then records.

But it was 1925 that The Charleston really exploded. When James P recorded his piano roll. When Paul Whiteman recorded his hit version.

Paul’s version is a typically luscious and extravagant affair, a very “Rhapsody In Blue” approach to “The Charleston.” An approach that required two pianos! But what likely lured flappers onto the dance floor most was the out-of-breathe dance instructor – at least I think that’s what he’s supposed to be – panting “one – two – (incomprehensible)” and then later “WHATCHA! DONG-DA! DIN-DON-DA-DON! SH-CHA! SH-CHA! SH-CHA DONG! SH-CHA DONG!” Which as dance instructions go, is probably the most unhelpful of all. It’s a lucky thing then that we have this instructional video.

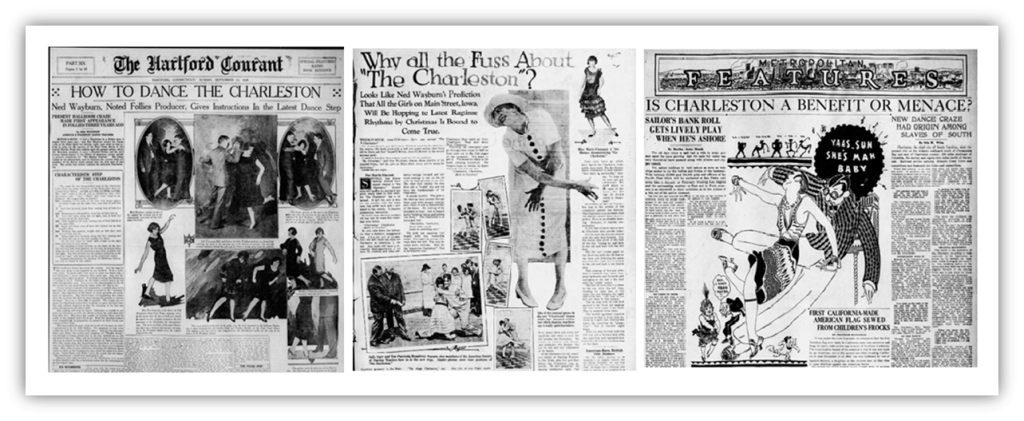

1925 was also the year that The Charleston became a fully-fledged media obsession.

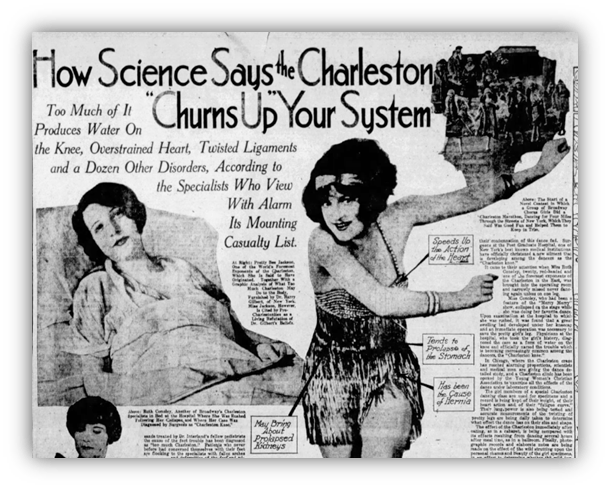

And my personal favourite: “How Science Says The Charleston ‘Churns Up’ Your System.”

With a sub-heading just as terrifying:

“Too Much Of It Produces Water On The Knee, Overstrained Heart, Twisted Ligaments and a Dozen Other Disorders, According To Specialists Who View With Alarm It’s Growing Casualty List.”

“Dance The Charleston” it began:

“and dance yourself into physical collapse is the warning that science now sounds. The ten million or so young people who nightly strut the latest dance craze… are “hoofing” their way to the hospital – and perhaps to the cemetery.”

Concerning stuff!

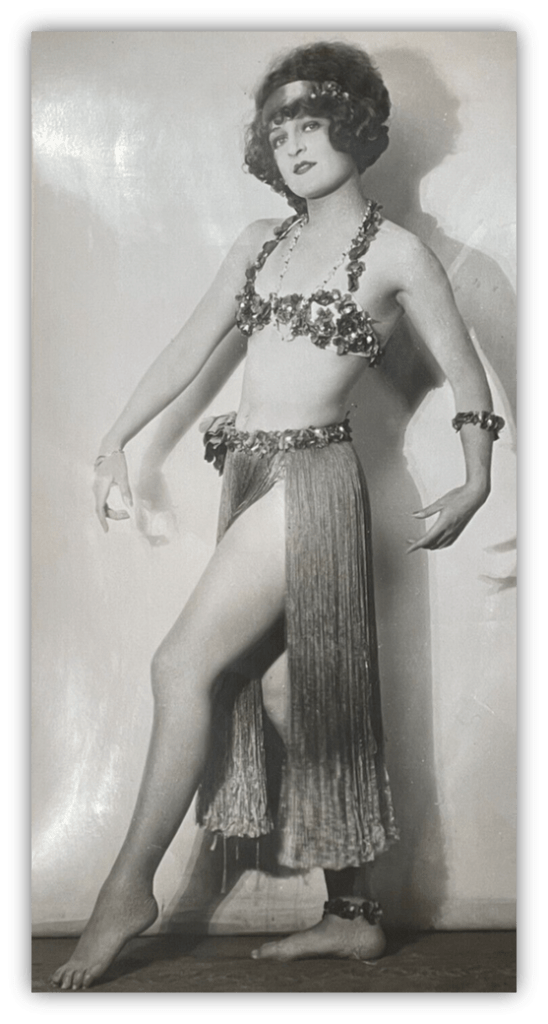

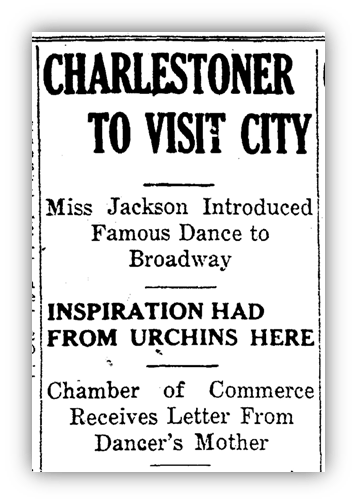

That Charlestoning flapper in the article is Pretty Bee Jackson, Charleston Sister Number One!

She was, as they say, a character.

Pretty Bee appeared to have one goal in life, and that was to convince everyone that she was the true inventor of the Charleston.

Being a white girl from Brooklyn, Pretty Bee’s claims of having invented a dance originating amongst Black folk on the outskirts of Charleston, was always going to lack credibility, but lacking credibility was not necessarily a problem in 1920s America. Pretty Bee travelled all over America – also occasionally popping over to Europe – dancing the Charleston and telling everyone who would listen that it was she who had come up with the dance.

Pretty Bee may not have invented the Charleston – and just to be clear, she did not – but she may have done more than anyone else to spread the dance across the globe.

Most people seemed willing to at least pretend that they believed her and to nod politely, but some raised their eyebrows, skeptically. Pretty Bee could not let that stand! She simply had to prove that she was the original Charlestoner! (even though, and I think I’ve made this pretty clear, she very clearly wasn’t)

Pretty Bee had a plan: she was going to do the Charleston, in Charleston!

In front of movie cameras! And receive a key to the city for her efforts!! Her mother wrote the Charleston Chamber Of Commerce a letter outlining their request, which the council was so perplexed about that they gave it to the local newspaper to print.

It included this Pretty Bee Origin Story:

“About two years ago my daughter, Miss Beatrice Jackson, while visiting friends in Charleston, saw a group of negroes doing a peculiar, rapid dance to the accompaniment of a lead pipe beaten on a soap box. She immediately saw possibilities in the lightning steps of the negroes and haunted the waterfront studying and analyzing the dance. Finally, upon her return to New York, she set to work developing steps from the basic foundation the negroes gave her. This dance she named the ‘Charleston’ and introduced it to Broadway.”

The Charleston Chamber Of Commerce were bemused.

As they were about anything to do with this dance which had, with no effort on their part, taken over the world. They struggled to decide if this was actually good for Charleston (the town) or not.

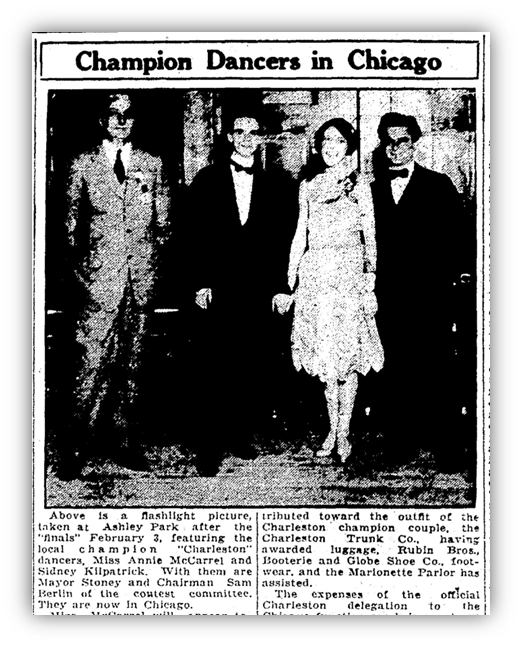

But when they found out there was a national Charleston competition in Chicago?

They figured they simply had to win it and set out to find the best – white – Charleston dancers in Charleston. Although there was some concern that, since there weren’t a whole lot of white Charleston dancers in Charleston, their chances of winning were low, the organizers had promised that the Mayor of Charleston would be invited to make a national broadcast speech. What mayor doesn’t want that?!?!

Long story short, the mayor and Charleston’s best Charlestoning couple went to Chicago, the mayor gave a speech – which included such hot takes as “if the negroes hadn’t come to America, we wouldn’t have had the War Between the States, perhaps, but we wouldn’t have had the ‘Charleston,’ either” – and they came forth.”

Having been the honoured guests of a national dance competition:

Charleston (the town)

Began to feel a little more charitable to:

The Charleston (the dance)

…and Beatrice Jackson finally got to visit the town.

She could have just turned up of course, but she wanted to be treated like a dignitary, complete with official functions and newspaper journalists etc, and she was! She even had a movie crew make a newsreel about her. By the end of the newsreel all of Charleston was doing the Charleston, just like everywhere else.

Once again, I’m at a loss over how one rates something like “The Charleston.”

But it’s going to be stuck in my head all day.

Meanwhile, in Hokum Land:

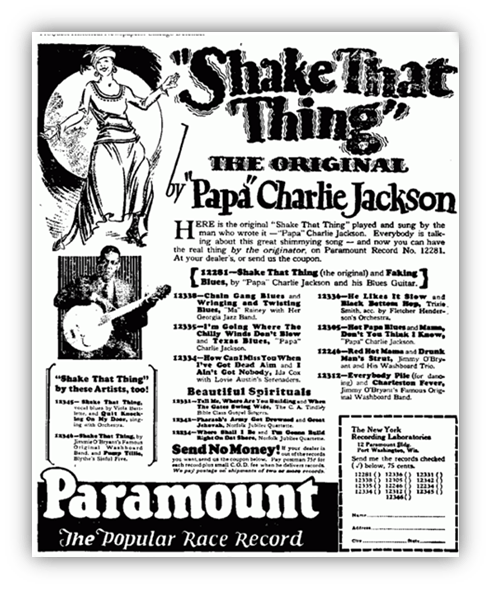

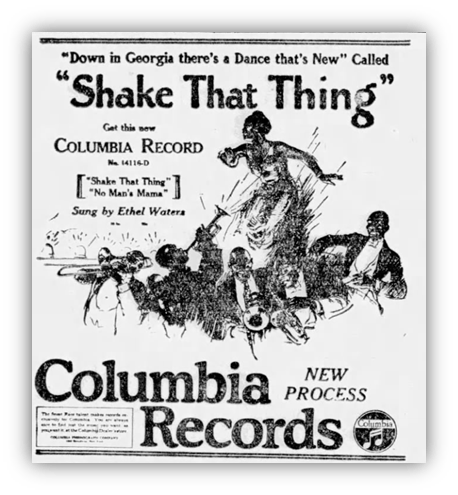

“Shake That Thing” by Papa Charlie Jackson

How many times in your life have you heard a song telling you to shake that thing? So many times, right?

Maybe not that exact phrase…

- Maybe it was “Shake Your Groove Thing”

- Or “Shake Ya Tail Feather”

- Or “Shake Ya Ass”

- Or “(Shake, Shake, Shake) Shake Your Booty”… but whatever the wording, the central message has been the same: to “shake that thing.”

It’s entirely plausible that you are sick and tired of being told to shake that thing?

It all began in 1925, with a man and his plunky-plunk banjo.

Or, if we are being technical, a guitar-banjo. A man, his guitar-banjo, and a catchy little dance-craze song called “Shake That Thing.” The dance-craze itself literally being shakin’ that thing.

A man who, if his photos are anything to go by, wasn’t just sick and tired of telling you to shake that thing, but sick and tired of life itself.

Shaking that thing may not have taken over the decade quite like “The Charleston” did, but the simplicity of the song, the simplicity of the directions – it’s literally just shaking that thing – and the apparent pan-generational appeal of the dance, gave the song legs.

The lyrics of “Shake That Thing” makes it sound as though shaking that thing is more popular than “The Charleston:”

The old folks like it, the young folks too, the old folks showing the young folks what to do. Grandpa Johnson grabbed Sister Kate, he shook her just like she’s jellying on a plate.

- Old Uncle Jack? He’s the jellyroll king, just came back from shakin’ that thing.

- Old Uncle Moe? He’s sick in bed. The doctors say he’s almost dead.

Old Uncle Moe wasn’t even shakin’ that thing. All he was doing was watching other people shakin’ that thing. Clearly “Shak(ing) That Thing” was even more dangerous than “The Charleston.”

Papa Charlie’s original “Shake That Thing” was big.

But the Ethel Waters’ version – yes, her again – I’m really going to have to do a dedicated column on her sometime – was huge!

Ethel Waters took a very different approach. Ethel shakes her thing, but she shakes it sultrily, sexily and slow. It’s probably the slowest record called “Shake That Thing” ever recorded.

It was all a little bit too sexy for The Chicago Bee newspaper.

A rather stuffy and self-described “wholesome” Black newspaper wrote a scathing critique of the phenomenon when they heard that it was the biggest record Columbia had ever produced.

“The American people crave filth and dirt” they explained, “they thrive on a diet of mud”, and “Shake That Thing” was “the most vulgar, sordidly suggestive” song on the market, and, “compared to which “Yes, We Have No Bananas” was as a production from Bach or Beethoven.”

Really? All Papa Charlie and Ethel are doing is telling you to shake that thing?

I hate to tell The Chicago Bee, but this was just the beginning. “Shake That Thing” was about to inspire a whole new genre: Hokum.

The word “hokum” already existed in a non-music describing capacity, but it was still pretty new, seemingly appearing out of nowhere at the beginning of the 1920s and instantly being used by everyone, regardless of whether they knew what it meant or not.

An article from 1923 – upon noticing the word was absent from both slang dictionaries and the regular kind – tried to get to the bottom of it.

After several twists and turns in their investigations, they came up with: “a word coined by actors and used by them as applying to a sure-fire laugh, wrongly used by persons not connected with the stage as meaning deceptive talk or action.”

In just a few short years, hokum would evolve into washboard and jug bands and other super fun stuff, much of which would also feature a kazoo.

Whereas the phrase “shake that thing” would take multiple decades before it finally found its true calling:

Papa Charlie’s “Shake That Thing” is a 9. Ethel’s is an 8.

Nice reporting on the Charleston. I chose it as the song for South Carolina in my state-by-state musical trek from Memorial Day weekend. I went with the Enoch Light version.

I never knew the origin story of Sweet Georgia Brown. The 1949 recording by Brother Bones and His Shadows is the one I am familiar with as it was used as the theme for the Harlem Globetrotters for years. I think that’s how a lot of us from my generation knew the song.

And now for a brand new feature! It’s the official It’s The Hits Of July-ish 1925 Playlist! Jampacked with snazzy jazzy ditties for you to Charleston, and just generally shake that thing to!

https://open.spotify.com/playlist/25Eiq9gIctlcVekJBIAnkX?si=d927923bea394ab5

Dan, where do you come up with lists of what was popular back then?

My primary source is:

https://www.musicvf.com/top-songs-of-1925#gsc.tab=0

Occasionally I have a look at Barry’s Hits Of All Decades.

(Most of the songs on that playlist though are less chart hits and more underground classics)

OK, I’ve seen that page, but it’s been a while. Thanks!

On the country side of the tracks, Gene Austin and Carson Robison hit big with “Way Down Home”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Hw-By–tyk

I always wondered who Sweet Georgia Brown was. Not enough to look it up, but now I don’t have to. Good stuff as always, DJPD!

On my weekly radio show (wobofm.com 8-midnight Eastern Time, shameless plug), I always play the #1 song from 100 years ago. I just use what Joel Whitburn said in his Pop Memories book, since I know there were no REAL charts that old. Anyways…this whole month I’ve been featuring Ben’s “Sweet Georgia Brown”. Fun song!

I didn’t know “Shake that Thing”, so my education is enlarged today.

Billboard was still a general entertainment mag in those days. Check out the July 25, 1925 issue here:

https://www.worldradiohistory.com/Archive-All-Music/Billboard/20s/1925/Billboard-1925-07-25-.pdf

Very cool!

World Radio History has scans of nearly every issue of Billboard from 1894 to 2021

https://www.worldradiohistory.com/Archive-All-Music/Billboard-Magazine.htm

They’ve got tons of other old music mags as well from many different countries.

On my weekly radio show (wobofm.com 8-midnight Eastern Time, shameless plug),

Tuesdays, right, Link?.

Oops! Yes, Tuesdays 8-midnight, EDT