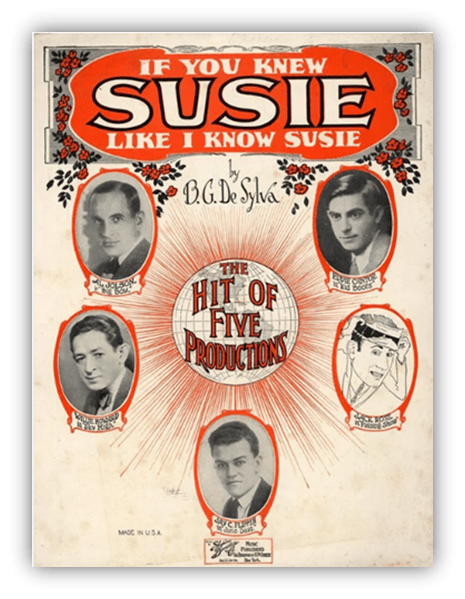

The Hottest Hit On The Planet:

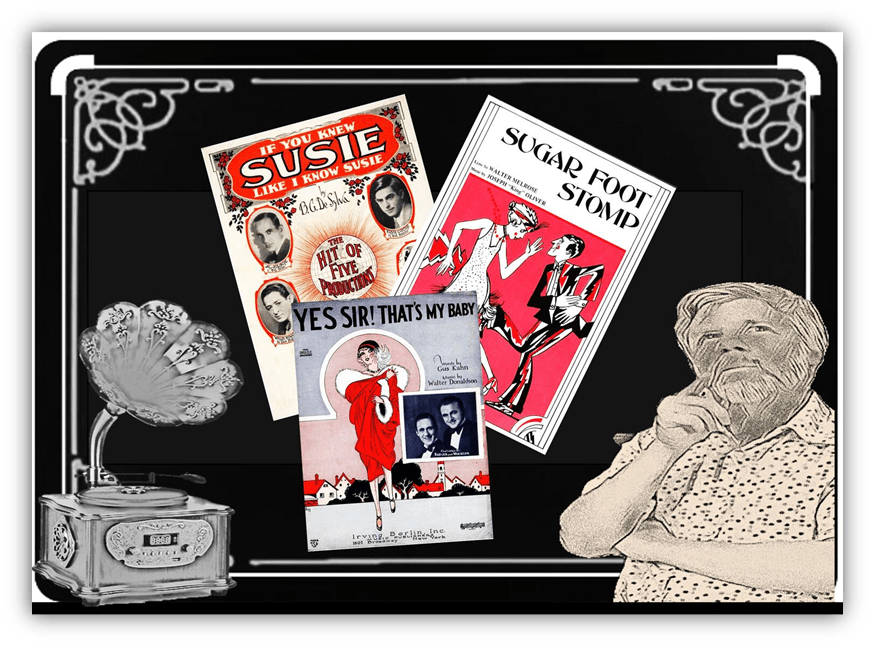

“If You Knew Susie”

by Eddie Cantor

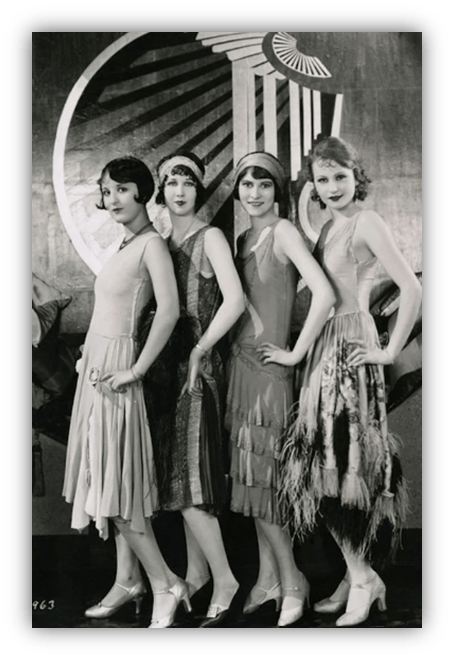

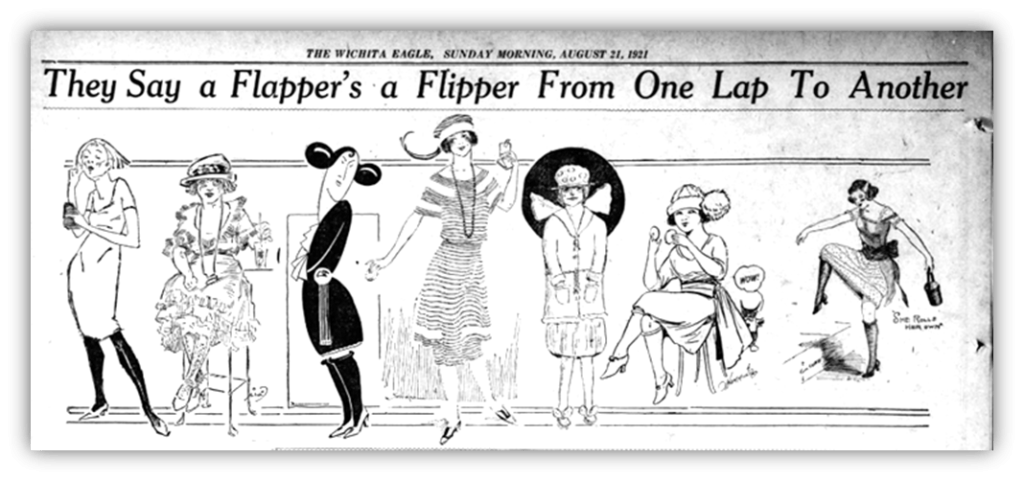

It’s time to talk about the flapper: the defining pop cultural image, the defining pop cultural sub-culture, of the 1920s.

And the primary media obsession as well. The media simply couldn’t get enough of them.

Articles revealing the precise definition of a flapper, how to identify a flapper and determine whether one was a member of your own family, appeared in virtually every newspaper, from sea to shining sea.

The Wichita Eagle’s contribution, “They Say A Flappers A Flipper From One Lap To Another” provided a handy list by which the reader could identify a flapper in their midst.

A flapper could also be identified by their tendency to:

- Wear “rouge”

- Bob their hair

- Wear short dresses

- Hate chaperones

- Drink “lemon cokes” at “soda fountains”

- Not possess “a speck of gray-matter”

And most important of all – so important that it was printed in ALL CAPS – a flapper was “never FAT”.

Or, if you didn’t have the time to read those articles, you could simply listen to “If You Knew Susie (Like I Know Susie).”

For “If You Knew Susie (Like I Know Susie)” is a celebration of a flapper, in all her flapper-majesty.

“She wears long tresses

And nice tight dresses

Oh, oh, what a future

She possesses”“Out in public

How she can yawn

In a parlor

You would think a war was on”

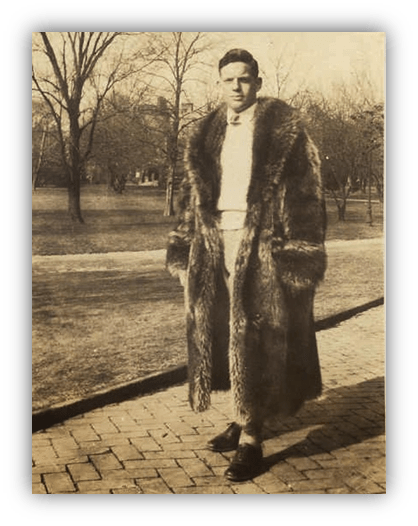

The flappers got all the media attention, but there was a male equivalent too.

If the phrase “flapper” wasn’t exactly flattering – it appears to have been derived from the slang term for a prostitute a generation or so before – at least there was a certain glamour to it, something that you couldn’t say about the term the guys got stuck with: “

“Cake-eaters.”

Nobody seems to know exactly why the male-flapper was referred to as a cake-eater. They were also referred to as Dollar Johns and Two-Cent Wills, a damning reflection on their tendency to be cheap. And also rug hoppers, a less-damning reflection on their love of dancing.

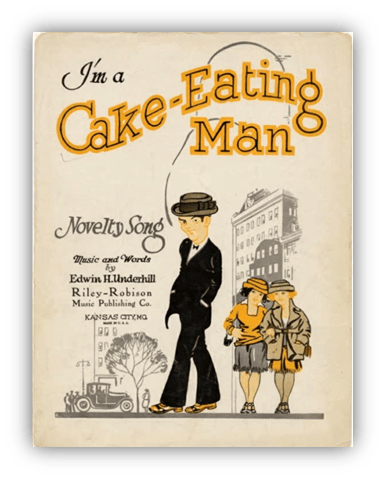

By 1922 there was a song called “I’m A Cake Eating Man”, the hero, such as he was, being a man who ate his cake where he could.

He liked a “dapper flapper that show(ed) a naughty knee, who dance(d) to naughty jazz and (wore) naughty lingerie.”

Suggesting that even in his own song, the cake-eating man is less interesting than his flapper girlfriend.

“I’m A Cake Eating Man” was not a hit. But one cake-eating man was:

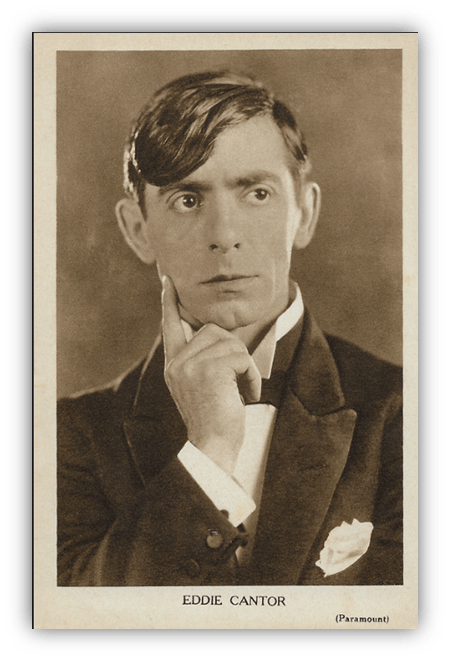

Eddie Cantor.

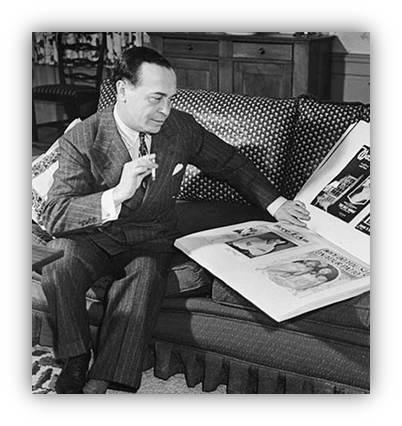

Eddie – or to use the name he was born with, Isidore Itzkowitz – had been the star of the Ziegfeld Follies in the late 1910s, where he was living the dream of constantly being surrounded by leggy chorus girls.

Eddie was so excited about these leggy chorus girls that he was constantly breaking into song about them. About all the wonderful girls that, we are led to believe, Eddie is dating, despite everything about him – his high-pitched-voice, his adoption of the mannerisms of a seven-year-old schoolboy trapped in a 20-something-year-old-body – suggesting that this was highly unlikely.

Eddie was living the dream, and he couldn’t believe his luck. When it came to lovin’ the girls, Eddie was way ahead of the times.

In real-life however, Eddie was married, and had been for several years. In real-life, Eddie’s cake-eater credentials were poor. Eddie spoke his effeminate New York Yiddish accent with perfect diction, frequently using fancy words,

And occasionally wearing dresses, and impersonating female stars.

He’d sing songs with super-long titles, which seemed to feature about half the lyrics in them. His topical Prohibition-era hit for example, “You Don’t Need The Wine To Have A Wonderful Time, While They Still Make Those Wonderful Girls”, not to mention “When They Are Old Enough To Know Better (It’s Better To Leave Them Alone)” which is practically a novel-length work of literature.

As Eddie got bigger and bigger, he began to compete head-to-head with the biggest vaudeville performer of his, or any, age: Al Jolson. Or, ‘Jolie’ to his friends.

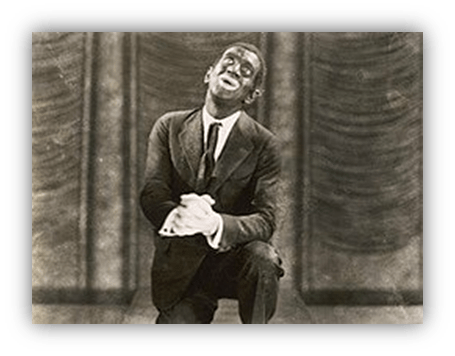

Eddie and Jolie had a lot in common, what with them both being Jewish entertainers who wore a lot of blackface.

But they both approached blackface in a different manner.

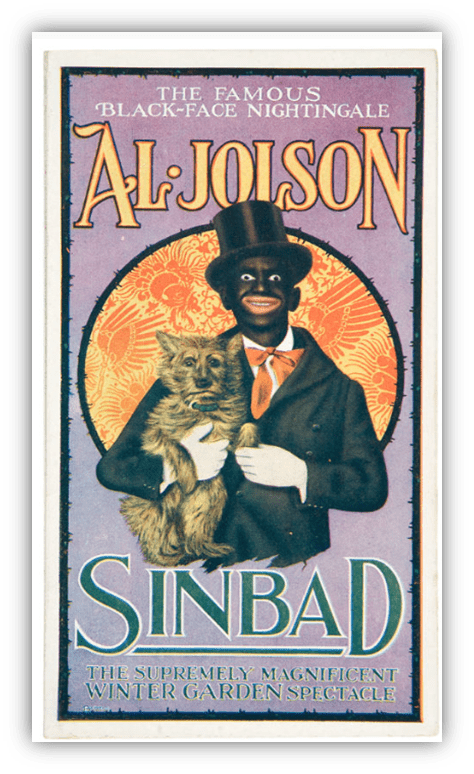

When Al Jolson performed in blackface, it was as a character named Gus, a porter whose primary duties included making wisecracks and outsmarting white people.

The audience loved it, and Jolie – always wanting to give the audience what they wanted – played Gus in pretty much every production he was in, regardless of whether it made much narrative sense. A musical based on Robinson Crusoe? Jolie played Gus.

A musical based on a dream sequence set in Bagdad? Jolie played Gus.

Eddie, on the other hand, wore blackface despite the fact that his character, voice, jokes and mannerisms, were all decidedly Yiddish. Although few people at the time appear to have found blackface offensive, everyone seemed to agree that a blackface Eddie Cantor it didn’t make a whole lot of narrative sense.

Eddie was the only vaudeville performer who could go head-to-head with Al Jolson, and come out the other side, if not victorious, then at least in one piece. And I mean that both in relation to phonograph sales, and just pure eye-boggling, crowd pleasing, energy levels!

But although Eddie could compete with Jolie, there was only one time that Eddie Cantor managed to beat him.

That was with a song by Jolie’s favourite Tin Pan Alley tunesmith, a song that had originally been written for Jolie, but that Jolie had foolishly rejected.

That Tin Pan Alley tunesmith was Buddy De Sylva:

A spoilt Hollywood kid who seemed to spend all his life at the beach.

This turned out to be perfect training for a Tin Pan Alley tunesmith, the beaches of California basically resembling a Ziegfeld chorus line in the sun. Whilst still in California, Buddy came up with the 1918 Jolson hit, “I’ll Say She Does,” in which he brags about how he has a brand-new sweetie, one who – and this was considered quite risqué at the time – sits on his knee! Very clearly, this is basically an “If You Knew Susie” prototype.

Once “I’ll Say She Does” was a hit, Buddy moved to New York to become one of Jolie’s favourite sources of hit songs. And also to marry a Ziegfeld chorus girl! He too, was living the cake-eating dream!

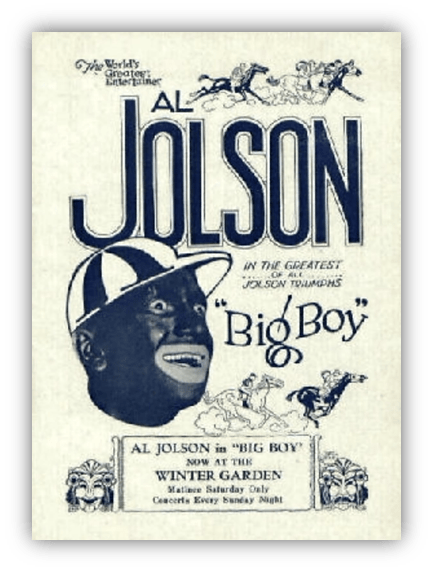

“If You Knew Susie” was written for a Jolie vehicle called Big Boy in which, once again, he played Gus.

This time, in addition to his wisecracking porter duties, Gus had a side-hustle as a jockey in the Kentucky Derby, riding a horse with the titular name. They had real live horses on the stage, racing on treadmills.

What Big Boy didn’t possess however was a character named Susie, but that was not considered an issue at the time. The songs in your average musical had nothing whatsoever to do with the plot. The plot often barely existed, other than to fill in the time until the next song.

This was particularly the case when Al Jolson was in the musical.

If he noticed that the crowd was getting bored, or if he was getting bored with the plot himself, he’d simply stop the show, send the rest of the cast home, and give a concert for the rest of the night.

You get the feeling that this was exactly what the audience was hoping for.

Jolie didn’t record “If You Knew Susie.” He didn’t feel it was for him. I blame the, “in the words of Shakespeare, she’s a wow!” line.

It’s not that Jolie didn’t like singing ridiculous lyrics. The Jolie oeuvre is full of ridiculous songs. But, “in the words of Shakespeare she’s a wow!” may have been a wow too far. It was not, however, a wow too far for Eddie. Only two years earlier he’d had a hit with “Oh! Gee, Oh! Gosh, Oh! Golly, I’m In Love!” “Suzie” was on-brand for him.

Having kicked “Susie” off by quoting Shakespeare, Eddie proceeds to sing “If You Knew Susie” the way that he sang so many of his songs; as if it were a stand-up comedy routine filled with “take my wife… please” jokes!

Eddie makes pervy remarks about her chassis, quite possibly the first instance of using a car as a metaphor for a woman’s body in pop. It would not be the last.

Then we get a list of all things that Susie does:

- She spends Sunday praising the Lord

- But on Monday she’s as busy as a Ford.

Gee! Another car metaphor!!

Then there’s this whole surreal bit about her lips being so hot they burn Eddie’s moustache off. All of this is backed by a banjo and sliding trombones to emphasize the punchlines, and Eddie goes “WOW!!!!!” and “Oh! Oh!” so often, and with such commitment, that they no longer come across as affectations. “WOW!!!!!” and “Oh! Oh!” are now official Eddie Cantor lyrics

“If You Knew Susie (Like I Know Susie)” is a 7…

…Unless your name is Susie, in which case you’ve probably heard it all your life and are heartedly sick of it, and it’s a 1, and I don’t blame you.

Meanwhile, in Ukulele Land:

“Yes Sir, That’s My Baby”

by Gene Austin

You know the one: “yes, sir, that’s my baby, no, sir. I don’t mean maybe, yes, sir, that’s my baby, noooowwwwww”

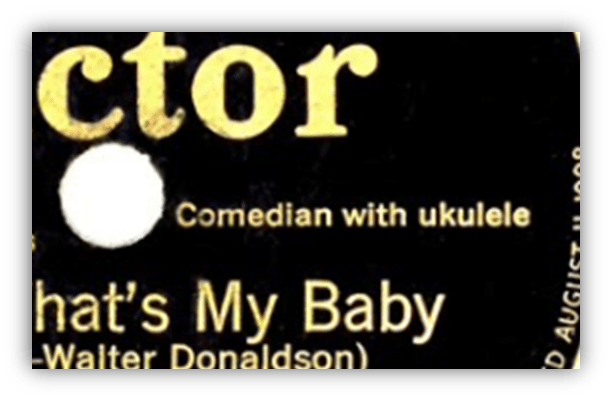

“Comedian with ukulele.”

That’s what it said on the label.

This, presumedly, was considered a selling point, not a warning.

And then, further down, in the slightly-smaller-print, “ukulele and jazz effect by Billy (“Yuke”) Carpenter.” Not just ukulele, as if that were not bad enough, but “jazz effect” as well, whatever that might be.

By Billy (“Yuke”) Carpenter, whoever that might be.

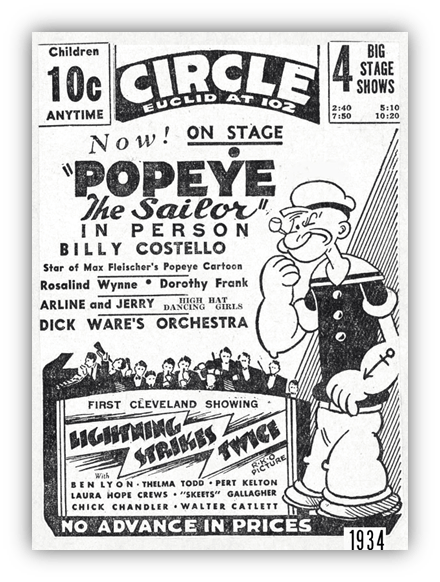

(It turns out that Billy (“Yuke”) Carpenter was a pseudonym of Billy Costello, and for a second there I was excited… you mean as in Abbott & Costello? But no, Costello was, of course, Lou.)

(Billy Costello was, however the voice of Popeye, which isn’t nothing)

As for “jazz effect”… that, it turns out, means “scatting.” It means making trumpet noises with your mouth.

Billy doesn’t only scat like a trumpet though, he also throws in a couple of trombone smears in. Despite arguably being the break-out star of “Yes Sir! That’s My Baby,” “Yuke” never quite became a star. At least not as a ukulele strumming “jazz effects” guy.

Then again, there was a lot of competition.

America was trapped in a ukulele fad, and it couldn’t get out!

Even worse, it was a “ukulele with scatting” fad! “Yuke” was not the only one trying to make a name for himself in the “ukelele with jazz effects” game.

There was Johnny Marvin, there was Cliff Edwards, both of whom had some huge selling – probably would have been Number Ones if Number Ones existed at the time – records.

Ukeleles were cheap. Ukuleles were easily transportable.

You could go up to any small-town radio station and offer to sing a song or two.

Didn’t have a backing band? You didn’t need one, you just scatted their parts!

The ukulele fad probably appears bigger than it really was though.

Sure, there were records by Ukulele Luke, Honey Duke and his Uke, Jimmy May and His Uke, Jack Lane and His Uke…

The thing was, though:

They were all Johnny Marvin. He wasn’t just a one-man band… he was a one-man fad!

Johnny’s probably-a-Number-One – “Breezin’ Along With The Breeze” – doesn’t just feature a ukulele and doesn’t just feature “jazz effects”, but a dash of yodelling as well! It’s all of the most annoying things in the world all at once!!

Then there was Gene Austin, who rode the ukelele wave all the way to becoming arguably the biggest pop star of the late 1920s.

Gene didn’t play the ukelele himself, at least not on record. He left that to “Yuke.”

Gene’s main asset was a laid-back Texas puppy-dog croon, one that he claimed was inspired by Al Jolson.

Not so much the way that Jolie sang, which Gene realized he could never match, and so didn’t even try, but the way Jolie described his Mammy singing. “Since he was always talkin’ about how his mammy used to croon to him,” Gene used to say, “I just croon like his mammy.”

Gene’s other key influence was singing cowboys. The kind that were constantly passing his childhood home in Texas.

Gene liked to sing their songs around the house, leading to Gene’s mother banning him from associating with them.

This was not because she thought singing cowboys would be a bad influence on young Gene, she was simply worried that little Gene would get stomped upon in a stampede.

Gene’s success can also be explained by so many of his songs being about everybody’s favourite media obsession.

Naturally, I am referring to flappers.

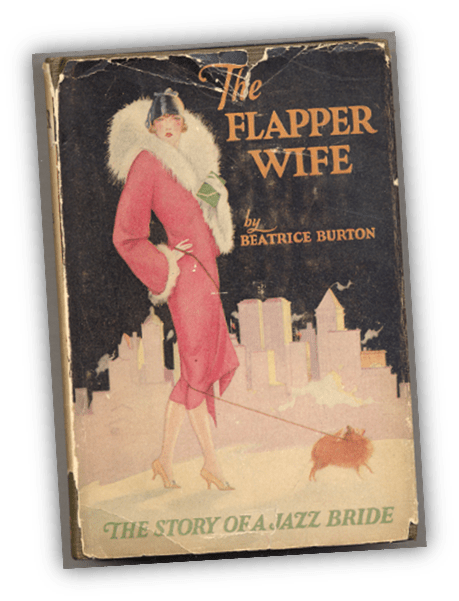

Gene sang about flappers with the sense of amazement that you might expect from a small town Texan boy who had never seen such wonders before. One of his earliest hits had been “The Flapper Wife.” It was the theme song for a serial radio drama.

But before it was a radio serial, The Flapper Wife had been a novel.

And before it was a novel it was newspaper serial. The Flapper Wife was a hit across multiple media formats.

Novels about flappers were a booming industry in the 1920s:

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is obviously the classic of the form, but there were many imitators. Although Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is a parody of a certain sub-species of flapper, it’s a parody that comes from a place of affection. The Flapper Wife (the book) on the other hand does not come from a place of affection. It was written by Beatrice Burton – who got a songwriting credit for the hit song version – an author of nothing but reactionary pulp-fiction morality plays.

The Flapper Wife, whose name is Gloria, doesn’t “say” things. She “shrills”! She dreams of marrying a rich man, and so she marries the first lawyer she sees. But: jokes on her, he turns out to be poor. Beatrice relishes in her fictional creation’s misfortune.

Gene Austin was far more charitable in his portrayals of flappers. In fact, he was gushing.

When Gene sang of dating – or better still, marrying – a flapper, he sounded as though he couldn’t believe his luck. He sounded like Eddie Cantor.

Or at least how Eddie Cantor would have sounded if he were a singing cowboy.

There was another good reason for sounding like Eddie Cantor when singing “Yes Sir, That’s My Baby.”

Legend has it that it was written:

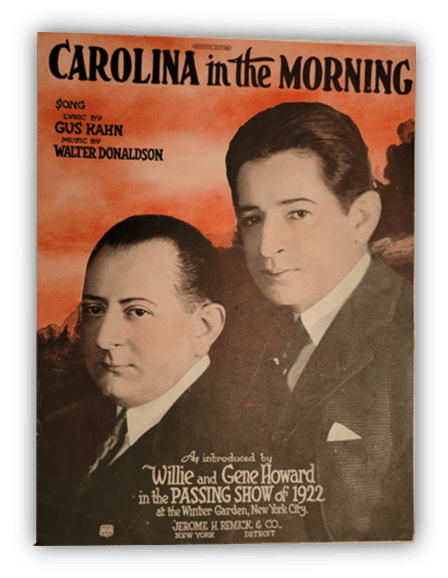

– by Gus Kahn and Walter Donaldson who had already written “Carolina In The Morning” and much else –

… in Eddie Cantor’s mansion, whilst watching his daughter, Marjorie, play with a mechanical pig. One that, when it walked around, made a rhythmical sound, similar to that in the song’s melody. And since they were watching a baby, whatever could they write a song about?

That means that Eddie was – indirectly at least – responsible for two of the biggest hits of 1925. Because “Yes Sir, That’s My Baby” was just as big as “If You Knew Susie.” Maybe even bigger. An argument could be made that I should have given “Yes Sir, That’s My Baby” the Hottest Hit On The Planet slot…

Now I admit, “Yes Sir, That’s My Baby” doesn’t specifically mention that the girl is a flapper.

Gene had just married a flapper though, he had a flapper wife, so he clearly had flappers on his mind. But I can’t imagine any other kind of 1920s girl being at the receiving end of such a preppy performance.

The love interests in Gene’s other hits though? Definitely flappers.

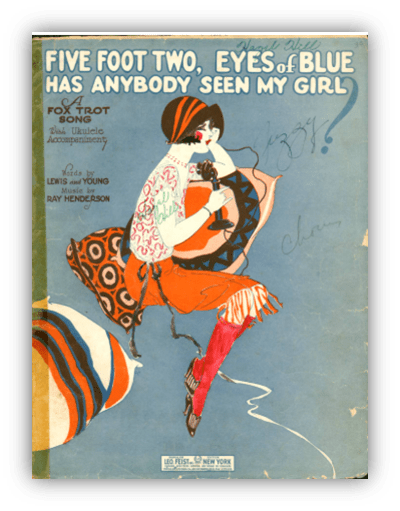

“Five Foot Two, Eyes Of Blue” for example.

You know the one:

five foot two,

eyes of blue

but of what those five feet could do…

has anybody seen my giiirrrllll”

- The one that later goes, “could she love? could she woo? could she, could she, could she coo?”, in a manner that I’m pretty sure is supposed to sound like baby talk.

- The one that starts with “I just saw a maniac, maniac, maniac”, which is a great way to start a song.

We know that “Five Foot Two, Eyes Of Blue” is about a flapper because the maniac literally says “flapper? Yes sir, one of those.” We also know that she is moderately short.

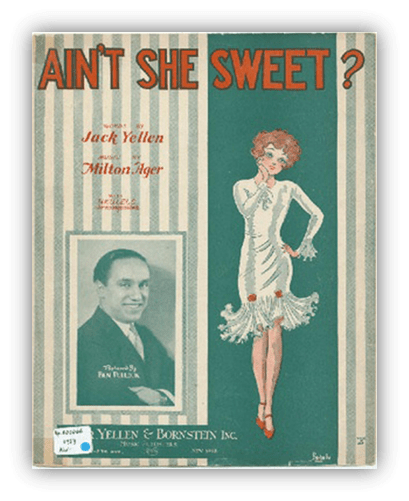

And you know “Ain’t She Sweet,” of course…

The one that goes:

“Ain’t she sweet?

See her coming down the street

Now, I ask you very confidentially… ain’t she sweet?”

… a song that, making full use of Gene’s inherent boyish charms, seems to consist of virtually nothing but the endearing cake-eater slang: he says “Doggone!” He refers to the girl as “neat!” He says “Gee Whiz!”… Twice!

That the girl in question is a flapper is somewhat less obvious on “Ain’t She Sweet”, than it was for “Five Foot Two, Eyes Of Blue.” The clues are there though:

“That flaming youth” for example, that is keeping Gene up all night, so he can’t eat a bite, doggonit? That’s most likely a reference to the movie – a mostly lost movie, sadly – and flapper expose Flaming Youth.

Flaming Youth starred famous flapper Colleen Moore.

Who had spent most of the 20s in a fierce battle with Clara Bow over who was the Main Flapper Girl.

Only a few scenes of Flaming Youth survive, mostly involving party scenes and Coleen looking at herself in a vanity mirror, applying fake beauty spots and dousing herself with dangerous quantities of perfume and talcum powder. This may have something to do with the fact that she had recently launched her own range of perfume and talcum powder.

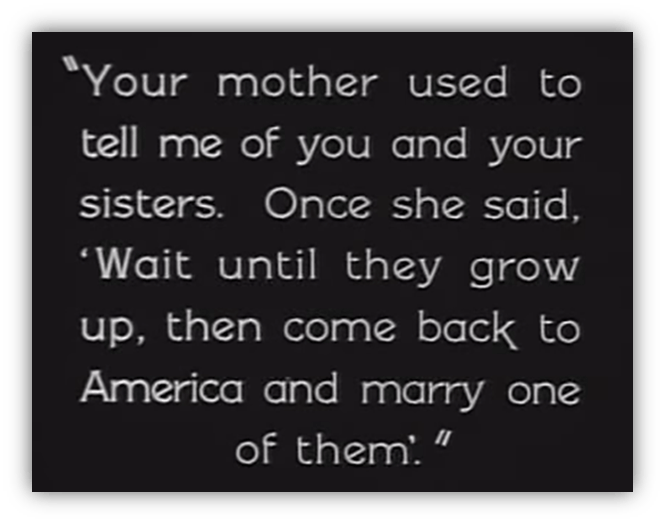

There was also this intertitle, which raises so many questions:

So, “Yes Sir, That’s My Baby”, “Five Foot Two, Eyes Of Blue” and “Ain’t She Sweet.” That’s quite a run of classic irritating earworms. And that’s before we deal with “Everything Is Hotsy Totsy Now” – sample lyric:

“I’ve got myself a brand new totsy, I’m her hotsy, she’s my totsy”

Which sounds exactly like you think it would.

Legend has it that Gene scoured the catalogues of pop songs that more established artists has passed on.

This is totally believable. These sound like songs that more established artists – artists with more sense – would reject. It was the songs others rejected that made Gene’s hits the biggest.

You will have noticed I’m sure, that Gene had left the ukulele behind for “Five Foot Two, Eyes Of Blue” and “Ain’t She Sweet,” a decision we can all be thankful for.

Even though poor “Yuke” might not agree. Although:

He had a career as the voice of Popeye to look forward to, so everything turned out okay.

“Yes Sir, That’s My Baby” is a 6.

Meanwhile, In Jazz Land:

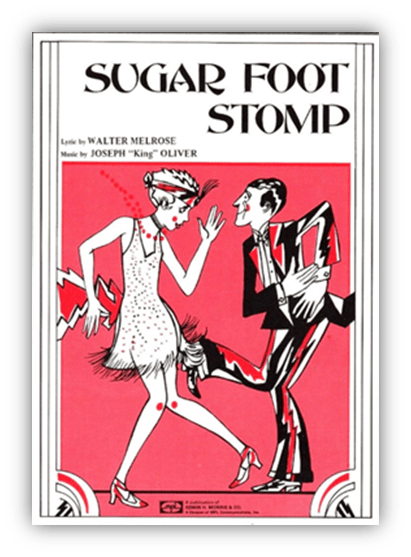

“Sugar Foot Stomp”

by Fletcher Henderson

“OH, PLAY THAT THING!”

Fletcher Henderson was a shy, bookish looking man with a barely-there pencil moustache, as was the fashion at the time.

A few years earlier he’d been the arranger and bandleader for Black Swan Records – the first Black owned record company – but now he was playing at the Roseland Ballroom, “the home of refined dancing”, right in the middle of the Theatre District, and signed to Columbia Records. His band was likely the only Black dance band that any New Yorkers outside of Harlem had heard of.

Some called him the Black Paul Whiteman, but other than the moustache and a tendency to wear tuxedos, they didn’t really have a whole lot in common.

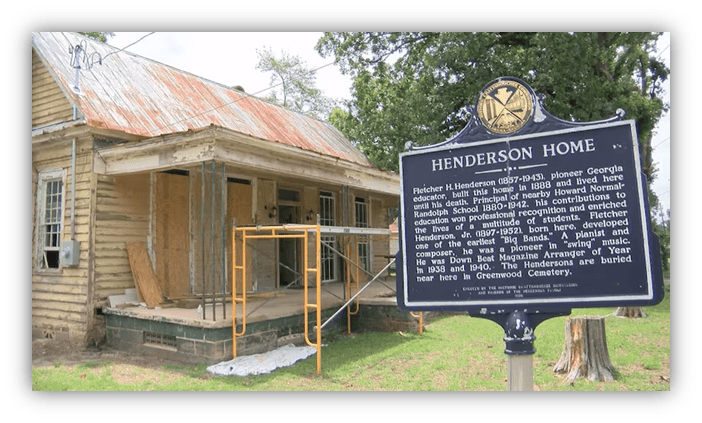

Fletcher Henderson had certainly come a long way from the weatherboard house in rural Georgia in which he grew up, although that makes him sound far poorer than he actually was. His father may have been born a slave, but by the time Fletcher came along, he was a professor. Of Latin!

Life for poor young Fletcher was rough. His parents were so adamant that six-year-old Fletcher learn to play the piano that they locked him in the parlour until they were satisfied that had practiced enough.

Fletcher’s band was pretty wild by the tame and genteel standards of the Roseland Ballroom – which I again need to remind you described itself as the “home of refined dancing’ – but they weren’t wild by the manic improvised soloing of the Dixieland jazz bands of the day. The musicians in Fletcher’s band played solos, but those solos were pre-prepared and written down. They were also extremely short; barely solos at all. It was controlled chaos, which the emphasis on controlled.

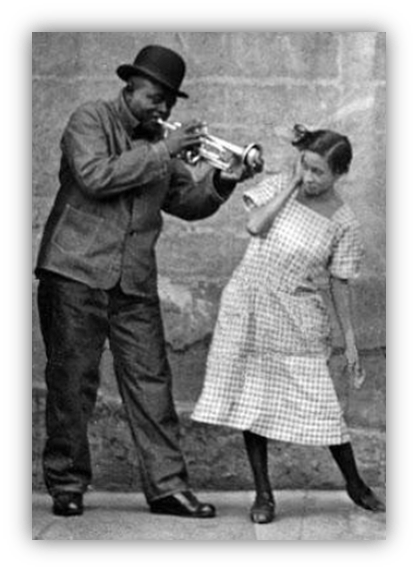

So Fletcher didn’t know what to do when a new cornet player turned up, straight off the train from Chicago:

Louis Armstrong. Originally, as I’m sure you know, from New Orleans.

He didn’t know what to do with Louis, He didn’t know what to make of Louis. Nobody – not in Fletcher’s band, not in the audience – seemed to quite know what to make of Louis. From a New Yorker-point-of-view, Chicagoans were practically country bumpkins. And New Orleanians? It’s possible they’d never even met anyone from New Orleans before!!

Louis found it difficult to fit in. He kept on doing things he thought of as normal, but Fletcher and the rest of the band thought of as uncouth.

Such as standing up every time he performed a solo. Louis was not aware that the polite, genteel and refined thing to do, was to remain sitting down.

And Louis wanted to sing. Although Louis’ voice would later become just as famous as his trumpet playing, I don’t think we can blame ol’ Fletcher for not being too crazy about that idea.

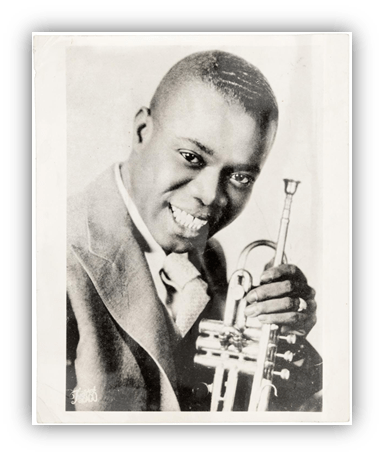

Fletcher didn’t seem to know what to make of Louis – he preferred his other trumpet player, Joe South, and gave him most of the solos – but he still seemed to like one of the tunes from Louis’ old band: “Dipper Mouth Blues” by King Oliver and His Creole Jazz Band.

King Oliver had been the reason why Louis had left New Orleans and moved to Chicago.

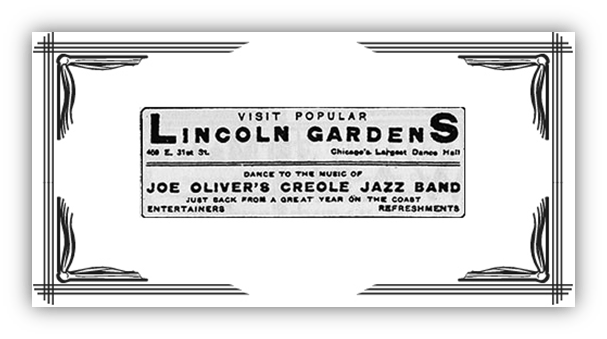

They’d previously played on steamboat cruises together, up and down the Mississippi. But then King Oliver left New Orleans, after the Army closed to brothel district down, leading to a sharp decline in places to play. But now he had a regular gig playing the Lincoln Gardens in Chicago.

Lincoln Gardens was the largest ballroom on the South Side, with a dancefloor large enough for two thousand feet.

It also had a giant ball hanging from the ceiling, covered in pieces of broken glass. When a light shone upon the ball, refracted light sprinkled all over the room. This wasn’t the first mirror ball – the invention of which had been patented in 1917 – but it must have been one of the biggest!

Given the size of the establishment, King Oliver realized that his band needed a little more horn-power. Needed something who could play the cornet loud enough to be hear at the back of the room. And he knew exactly who to call.

For if Louis Armstrong was famous for anything, it was his ability to play the cornet really loud.

That young slip of a girl is Lil Hardin, the piano player in King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band.

Also, Louis’ girlfriend. (He was very shy; she had to make the first move.)

Then wife. And basically, his manager as well.

King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band soon became the hottest band in Chicago, as was confirmed when they cut a record.

Admitedly it was for a tiny label run out of Richmond, Indiana, the studio located right next to a railroad track, so that every time a train passed by, the band had to take a break and take another take. But it still counts. They recorded for Gennett Reocrds, a side hustle for Starr Piano Company. Initially the label was called Starr Records, but stupidly, they changed it.

Gennett Records weren’t particularly fussy about what they recorded.

Their main strategy was to specialize in music that no other record company could be bothered with.

This is why they released polka records. This is why they released records of preachers preaching. This is why they recorded vanity records for the Ku Klux Klan, under the name ‘100 Percent Americans.’

King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band released a bunch of records in 1923, but the most relevant one here is “Dipper Mouth Blues”, a hyped-up jam with King Oliver playing solos right over the top of everyone else, whilst they simultaneously bust out solos in the background. It’s a whole wall of competing solos, but King Oliver makes sure he steals the show, makes sure that Louis is buried in the mix. It was his band after all.

I also quite like the rather charming “Chimes Blues,” featuring Lil tinkling away on piano.

Now, Lil had a theory – one might argue a conspiracy theory – that King Oliver had hired Louis as a power-move in the never-ending battle to be the Greatest Jazz Player Alive, keeping Louis under his thumb and at the back of the room where he could keep an eye on him and simultaneously sabotage his solos.

Lil decided that Louis should quit King Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band and go instead to New York, join Fletcher Henderson’s band and play on proper records by proper record companies, and gain a reputation as the hottest cornet player in America!

It sounded like a solid plan!

Lil was full of solid plans to make Louis a more successful and respectable man.

Coming from a New Orleans ghetto, Louis had never been taught which fork to use. Growing up in a middle-class neighbourhood in Memphis, Lil knew which fork to use. She taught him. Sadly, she forgot to tell him not to stand up when doing his solos.

Fletcher may have been ambivalent regarding Louis’ cornet blowing abilities, but he still recorded a version of “Dipper Mouth Blues.” Mind you, it may not have been his choice. Whilst Fletcher Henderson had previously been an arranger for Black Swan Records, now he had his own arranger:

Don Redman, who Louis showed the tune to, in sheet music form. Why do I get the feeling this was all part of Lil’s plan.

Fletcher wasn’t so crazy about the title though: “Dipper Mouth Blues” didn’t exactly scream out “home of refined dancing.”

It sounded faintly unhygienic. As best as I can tell, “dipper mouth” is not a medical condition, but it could be. And so Fletcher transformed it into the much sweeter sounding “Sugar Foot Stomp.” Which sounds like sugar-plum fairies having a marvelous time!

The comparison extends to the records themselves.

- Compared to “Dipper Mouth Blues”, “Sugar Foot Stomp” glistens and sparkles.

- Compared to “Dipper Mouth Blues” and its manic galloping clip-clops, “Sugar Foot Stomp” has a big stompin’ swingin’ beat.

- Compared to “Dipper Mouth Blues”, “Sugar Foot Stomp” sounds like New York, and not the side of a railroad track in Indiana.

One thing however stays the same. Both versions feature the part where the band stops on a dime, and someone cries out “OH, PLAY THAT THING!”

The most exciting part of “Sugar Foot Stomp” is surely Louis’s cornet solo, the solo that King Oliver had kept for himself on “Dipper Mouth Blues”, a solo that goes for about half the song. and yet something never stops being a hook.

Was Louis standing whilst performing his solo?…

I hope so. He certainly deserved to give himself a standing ovation.

Hey! According to Joel Whitburn’s opinion, “If You Knew Susie” and “Yes Sir! That’s My Baby” were long reigning #1 songs exactly 100 years ago, which means I’ve been playing them every week on my Tuesday evening radio show. The songs are like two peas in a pod. I’ve really grown to like them…especially “Yes Sir! That’s My Baby” because Gene sings it with such absurd gusto. He sounds like he’s having a blast, and it’s kind of contagious.

Oh, and my favorite line is from “If You Knew Susie”:

In the words of a Shakespeare, She’s a Wow!

Good stuff!

Somehow I knew Link would have the first comment here.

The only time I can find that Shakespeare used the word “wow” was in Coriolanus, Act II, Scene 1, when Volumnia says it. She doesn’t exactly use it in the way the song does, which is good because she’s talking about her son.

On the country side of the tracks, Vernon Dalhart had a big year in 1925 with songs like this one…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MPyy1M1_yug

What a great selection of tunes. I’m surprised how many of these I knew by name even though they’re from a hundred years ago. That’s the sure sign of classic songs. Good stuff, Dan!

Also, I like cake.

I didn’t know Susie but I’m pleased to meet her. Cake eater as an insult?! I’m proud to call myself one.

Yes Sir, That’s My Baby isn’t quite so enticing. I was onboard with it until the ‘ukelele and jazz effects’. As a one off they were an entertaining diversion but I dont fancy giving them repeat listens.

Mmm, maybe “If You Knew Susie” wasn’t quite as famous as I thought then.

Admittedly, I mostly know it because my mother’s name was Sue, and my father used to sing it at her all the time, probably not aware that he was boasting to us children that our mother was a firecracker in the sack.

He also used to randomly cry out “MY NAME IS SUE… HOW DO YOU DO?” for equally baffling reasons.

When I was in college about 6 of my friends got ukuleles. You’d be at the house drinking beer etc and suddenly one would say “you wanna uke it up?” And they’d scurry off to get their tiny annoying guitars… why? Who wants poorly sung ukulele renditions of Pixies songs?

It was the early 1990s, so it was like they went away for winter break and came back with ukuleles and piles of pogs… again, why?

The Pixies are coming to my neck of the woods. They added a second show. I almost missed seeing Frank Black. (The Mountain Goats are slated to be here in April.)

It’ll be my first concert since catching all four Dar Williams shows last year.

Was “Velouria” on the playlist? It’s my favorite Pixies song.

I don’t remember that one. Definitely “Gigantic” and “Tony’s Theme.” Also “Driving on 9” from the Breeders and “Detachable Penis” from King Missile was played in multi-uke format.