The Hottest Hit On The Planet:

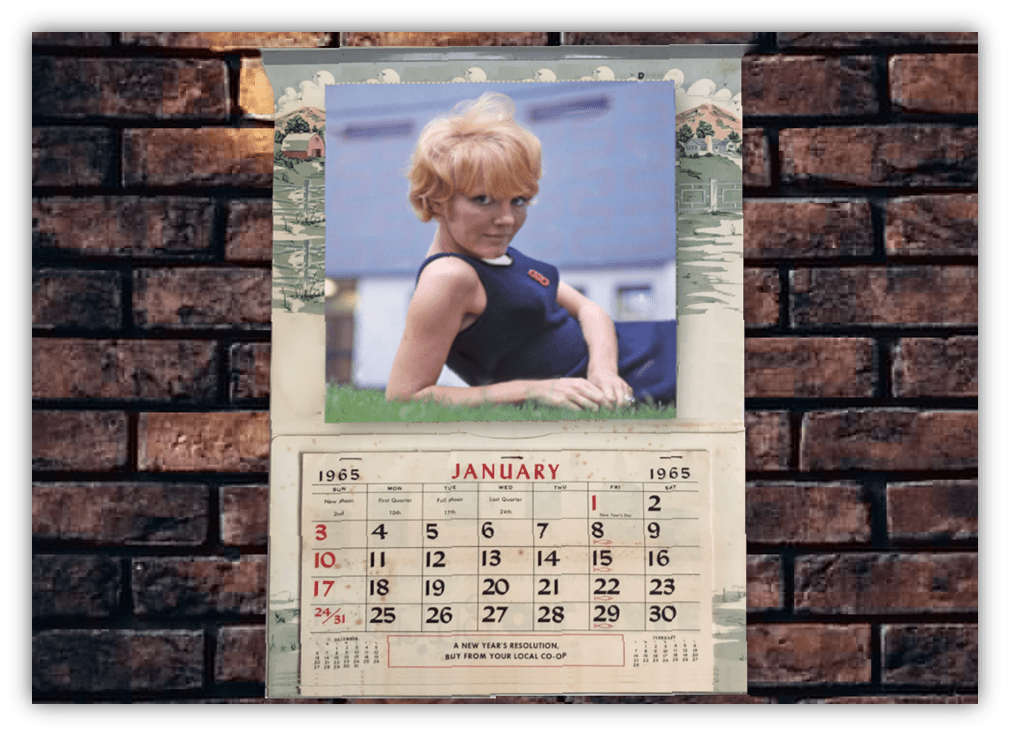

“Downtown” by Petula Clark

It was the end of 1964. It was the middle of the British Invasion. The Americans were obsessed with everything British. Meanwhile, the British were obsessed with everything American. This was nothing new: the British were always obsessed with America. They just don’t like to admit it.

America had New York. And the bright lights of New York. And the skyscrapers of New York. London had, what? Big Ben?

The BT Tower, which looked like Dr. Who’s Sonic Screwdriver?

And New York had the Brill Building, towards which Tony Hatch was headed to learn how to write classic pop songs. Whilst he was there, Tony did what every tourist to New York does. He headed to Times Square.

Because, sure, London has its own Times Square, except that London’s Times Square is a Circus.

It’s called Piccadilly. And that’s clearly not the same thing: Piccadilly never caused Tony Hatch to have the “Downtown” melody suddenly spring into his mind, as he watched neon signs go on.

And so, as 1964 turned into 1965, the biggest song coming out of Britain, was not by The Beatles:

But by an enthusiastic tribute to neon-soaked New York, performed by a girl from Surrey whose childhood home didn’t even have electricity, and who may not have ever even been to New York before (she definitely hadn’t performed there before… but she did tour Canada quite a bit, since, as you will learn, she was big with the French)

Tony certainly got a lot out of the New York trip. He certainly learnt how to write a classic pop tune, the production of which seemed to have come straight out of the Phil Spector “little symphonies for the kids” book.

There are signs within “Downtown” that Petula is far from being a kid herself, however. She’s dancing to the bossa-nova for one thing, and only grown-ups did that. For her Ed Sullivan performance they seem to have dressed her up to look like that other British superwoman of 1964-65: Julie Andrews. I’m getting some Mary Poppins vibes. Is there really much difference between “Downtown” and “Let’s Go Fly A Kite”? Or “My Favourite Things” for that matter?

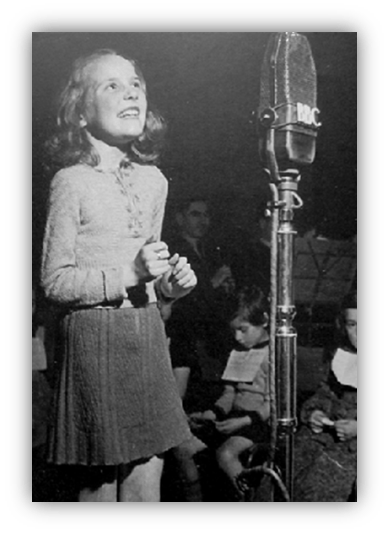

But Petula wasn’t quite as far from being a kid as she looked in that Ed Sullivan performance. Sure, she’d had hits in the 1940s but she had literally been a kid then. A kid with the demanding job of inspiring the country to keep calm and carry on, during the war.

A kind of lovechild between Shirley Temple and Vera Lynn. An eight-year-old kid who first sang on the radio in an underground bomb shelter during the Blitz.

I’m not going to pretend that I’m conversant with Petula’s 1950s work. Looking at her discography, there’s one song called “Christopher Robin At Buckingham Palace” and another called “Three Little Kittens.” Typical 50s fluff then.

By early 60s Petula was being robbed of a hit when Little Peggy March’s version of “I Will Follow Him” blew up all over the world, although to be fair it probably would have helped if Petula hadn’t sung her version in French. But Petula was living in Paris by then and was married to a Frenchman. She had turned herself into a French pop star: some say she was as big as Edith Piaf!

So long as the career prospects for a girl singer in France were better than the career prospects for a girl singer in Old Blighty, then this seemed like a good move. But then 1964 came and English girl singers were everywhere.

Both Melody Maker and NME Readers Polls confirmed that Dusty Springfield was Queen Of The Scene, with newcomers Cilla Black and Shirley Bassey making moves.

(Millie was robbed!)

Petula, meanwhile, was stuck in Paris (not, to be fair, the worst place in the world to be stuck in). It was time to take a break from singing in French, go back to her mother tongue, and take over the world. How could she lose?

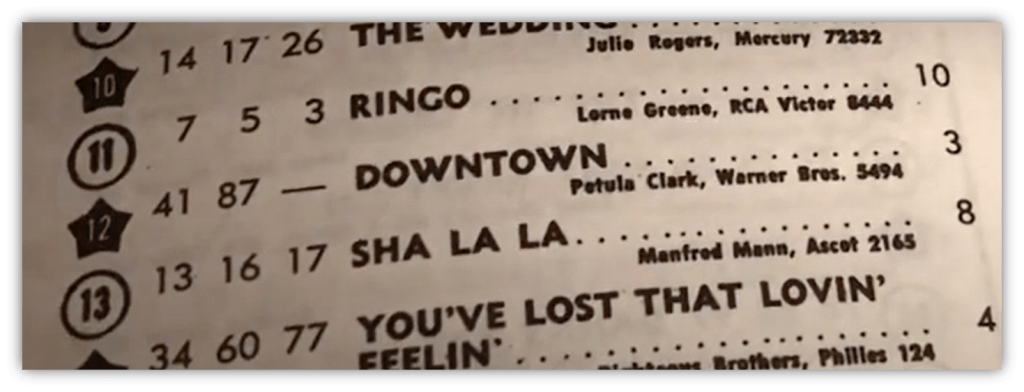

Soon “Downtown” was racing up the charts, first in the UK, then in the US:

Where they loved its quaint British translation of American hustle and bustle so much – the fact that it sounded like an advertisement: “don’t wait a minute more!!!” – they even forgave its geographic inaccuracies.

For, as many great minds have noted, Times Square is not Downtown. It’s mid-town. But no-one is going to buy a record called “mid-town” are they? They’d already bought a record called “Uptown.” It was by The Crystals. It was a very different kind of song. It was about a man from Uptown, getting up each morning and going Downtown, where everyone’s his boss, and he’s lost, in an angry land.

The Crystals’ Downtown isn’t a party town:

It’s the Financial District of Lower Manhattan. Thank God, Petula didn’t sing a song about the actual Downtown; she would have had to sing about Wall Street bankers!

The “Uptown”, in The Crystals’ case, is presumedly Harlem, where folks don’t have to pay much rent for a tenement. As opposed to the uptown in Billy Joel’s “Uptown Girl”, which is presumedly the Upper East Side. And now I think you can begin to understand why a British tunesmith might get a little confused by New York geography. (“Uptown” is a 10.)

Also because the entire concept of a ‘downtown’ is a uniquely American invention. Elsewhere, what Americans refer to as “downtown”, is known as the city centre, or old town, or Central Business District (CBD for short). The first neighbourhood to have been referred to as “downtown” may have been in New York, where all the action happened down by the docks, only barely above sea level. It was also down the bottom of maps, although that might just be a coincidence.

Eventually “downtown” became the accepted term for the city centre – or old town or Central Business District (CBD for short) – across America, regardless of whether it was near the ocean, of low elevation, or located at the bottom end of the map.

Given that, in New York, mid-town contains significantly more skyscrapers than downtown, it was a logical mistake for Tony to have made. In any other American city, Times Square probably would be considered downtown.

“Downtown’s” geographical inaccuracies are part of the song’s appeal. It’s that very wide-eyed cluelessness that makes it magical. It’s in the way Petula seems amazed by the fact that there are movie shows! You’d almost think Petula had never seen a movie show before! Had never heard the music of the traffic in the city! Had never lingered on the sidewalk where the neon signs are pretty! A jaded New Yorker could never.

There was only one way to follow up a song like “Downtown”, and that’s with a song like “Downtown:”

“I Know A Place.” Maybe you have difficultly telling them apart, in which case I’ll give you a clue; the Petula Clark of “I Know A Place” is more clued in. It turns out that Petula did know some little places to go, where they never close.

“I Know A Place” is also the song that sounds like “The Sesame Street Theme.” I refuse to believe that is a coincidence.

In “I Know A Place”, Petula appears to have discovered, not just “movie shows”, but “a cellar full of noise.” It’s as though Petula has stumbled upon an early-pre-Andy-Warhol-era-Velvet Underground gig, or something.

“I Know A Place” does for discotheques in underground cellars what “Downtown” does for Times Square. Both seem to be experiencing a mind-explosion that such a place could possibly exist: “it’s got an atmosphere of its own somehow” Petula marvels. She even seems fascinated by the tiniest, most pedestrian details: “at the door, there’s a man who will greet you, then you go downstairs to some tables and chairs.” Fascinating. (“I Know A Place” is an 8)

But underneath all this sense of wonder and astonishment is a bed of melancholia. “Downtown” is not just a party song. Here’s Petula in The Guardian:

“People generally think of it as a jolly song, but it isn’t.“

“When I sing it, I picture this person who’s alone in their room, lonely, feeling a bit worthless, close to a depression – then getting up and going out on the street to be among other people who are perhaps feeling the same way.”

“I have had those moments myself.”

Who knew that “Downtown” was such a downer?

“Downtown” is a 9.

Meanwhile, in Soul Land:

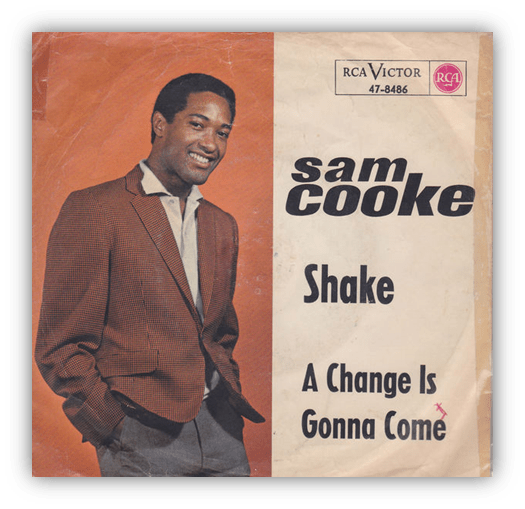

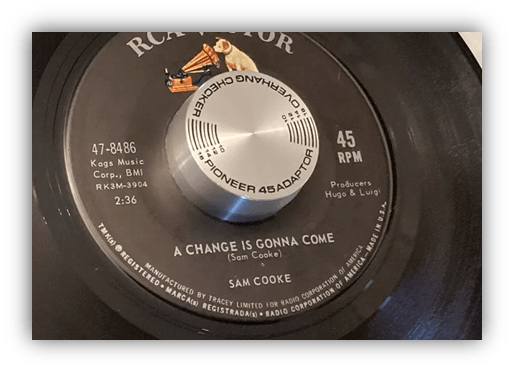

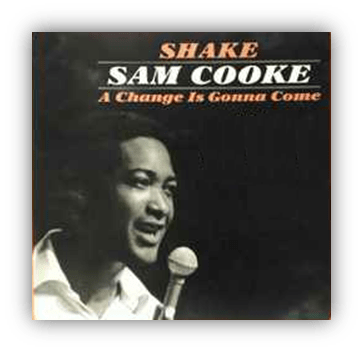

“A Change Is Gonna Come” by Sam Cooke

“Lady… you shot me.”

Those are the reported last words of Sam Cooke.

Sam Cooke uttered those words after he was shot – obviously – but before he was hit over the head with a broom. In the office of a seedy motel. Wearing nothing more than an overcoat and a single shoe.

This was not the way that Sam Cooke was supposed to go. Sam Cooke deserved a far more dignified exit than this.

We cannot know for certain what Sam Cooke’s final words were that night, of course. There’s little about that night that we can know for certain. The LAPD’s investigation into Sam’s death was grossly sloppy, as was the norm when the LAPD was investigating Black murders, even when the victim was a soul-singing superstar. Decades later, questions remain unanswered.

This is what we think we know:

Sam had met Elisa Boyer – described in the police report as “a real baby doll”, described in media reports as “Eurasian” – earlier that night at a bar, where he had been flashing a great big wad of cash around.

Sam spent the evening drinking a great many martinis and getting friendly with her. Nobody thought anything of it, because, well, this was Sam Cooke. Sam may have been married, but he was a good-looking, charming, pop superstar, and he went home with a new girl virtually every night.

Sam was so constantly in the company of ladies, that on one of the few nights he was deprived of female companionship, when he stayed at a British hotel that didn’t allow female guests, he was so sad that he wrote a hit song about it: “Another Saturday Night.”

“Man, if I was back home I’d be swinging two chicks on my arm”, Sam boasts. Although if his biographies are correct, and the rumours are true, it was probably closer to 20. (“Another Saturday Night” is an 8.)

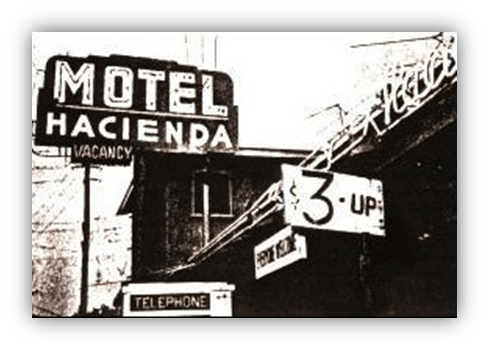

Sam and Elisa got into Sam’s car and zipped across to the other side of town. To the Hacienda Motel, on the corner 91st and South Figueroa, South Central L.A. Where, for $3 you got free radio, free television, a refrigerator, and they didn’t care what you got up to. It was the kind of establishment typically described as “seedy.”

Shortly after, Elisa was in a telephone booth, calling the police, telling them that she had been kidnapped, and that she didn’t know where she was. Elisa hadn’t wanted to end the night in a seedy motel. Elisa had asked Sam to drive her home. Sam had not driven Elisa home. Elisa was not into this. Elisa had escaped, whilst Sam was in the bathroom, taking Sam’s clothes with her.

When Sam walked out of the bathroom, he found himself without a girl, without clothes, and – since the wad of cash was in his clothes – without his wad of cash. Sam Cooke was not happy about this sudden turn the night had taken. Sam Cooke put on the only clothes Elisa had left him – an overcoat and a single shoe – and went out in search of her.

Soon Sam was banging on the hotel office’s door, yelling at the motel manager – Bertha Franklin, described in the police report as “stocky” – shouting “where’s the girl!”

Sam broke down the door. Bertha was, understandably, afraid. After all, Sam was still wearing nothing but an overcoat and one single shoe.

Also understandable – given that she was working in a seedy motel in South Central L.A – was the fact that Bertha kept a tiny pistol nearby. In the tussle that followed, Bertha would use that pistol to shoot at Sam Cooke three times. One of those times, she hit him.

That was obviously a convoluted story, and it only gets more so.

A month later Elisa was caught accepting money for sex by an undercover policeman. But the court figured that was entrapment and threw the case out. So there’s a good chance Elisa was a prostitute. Bertha was also a former-madam. None of which proves anything, but it’s enough to make some people theorize that the two of them were in cahoots with each other, to steal Sam’s wad of cash.

There are others who believe that the conspiracy went further than just Elisa and Bertha. There are those who believe that the LAPD, or the FBI, was involved. The bullet Sam was shot with, for example, was taken into evidence… and then lost and never seen again! Sloppy? Conspiracy? Cover-up?

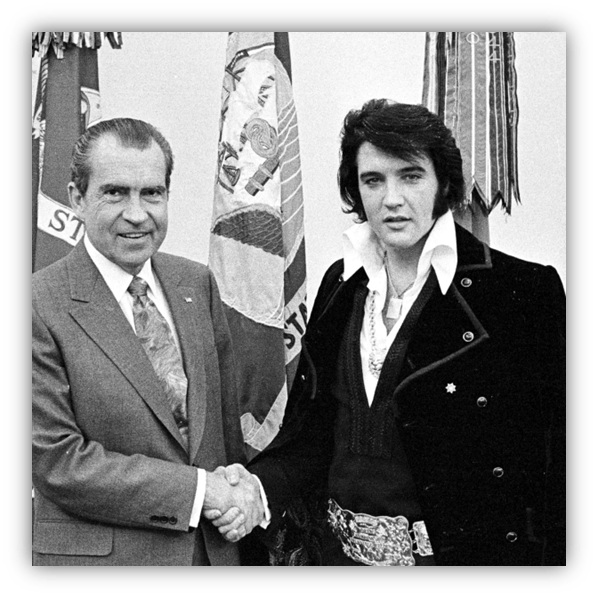

Even Elvis thought some dodgy shit was going down with the LAPD. Why would the LAPD and FBI conspire against Sam Cooke?

Well, Sam had become increasingly outspoken in the battle for Civil Rights. He was hanging out with Malcolm X and Mohammed Ali. He’d started his own record company, to sign Black artists, so that his friends could have hits as well. He once cancelled a show in Memphis when the promotors segregated the audience. Sam Cooke, so the theory goes, was becoming a growing threat to entrenched power structures.

Also, Sam Cooke had released “A Change Is Gonna Come”, The Anthem Of The Civil Rights Movement.

At the time Sam died, however, it was little more than a deepcut. It’s unlikely that the LAPD or the FBI was keeping tabs on Sam Cooke deepcuts. After Sam’s death however it was released as a single, or at least a B-side, the A-side being “Shake”, a joyous party-romp, that feels completely inappropriate given the circumstances (“Shake” is a 9.)

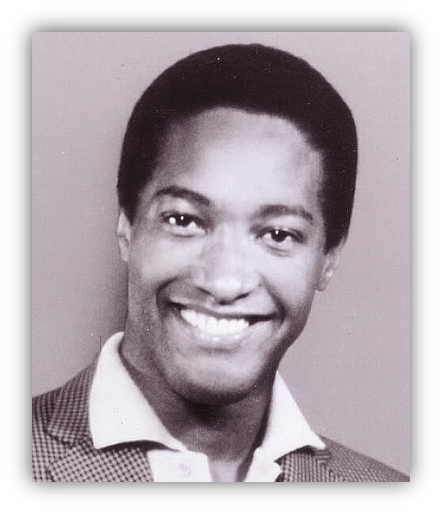

Sam’s death needed a conspiracy, otherwise it made no sense. Being shot in a seedy motel felt like such an un-Sam Cooke way to go. This was a guy, remember, who had originally become famous, as a teenage gospel singer.

Sam Cooke had been a gospel singer since he was a child.

His father was a Minister, so it was to be expected.

Sam’s father had moved the family north to Chicago when Sam was just a baby; moving away from Clarksdale, Mississippi, where Sam had been born… sort of near a river – the Sunflower River to be precise – but, almost certainly, not in a little tent.

Sam’s gospel career peaked with The Soul Stirrers, probably the biggest gospel group of the 50s. He had the voice of an angel.

He had the face of an angel. He made good use of that face. You may not think that gospel singers have groupies, but when you look like Sam Cooke, you do.

Then he decided to go pop. There was more money in pop. Also more groupies. Results were varied. For every “Wonderful World” (it’s a 10) or “Cupid” (it’s a 9), there was an “Everybody Loves To Cha Cha Cha” or a “Having A Party” (which are both very much lower).

It wasn’t Sam’s fault.

He was simply trying to be a pop star. For Sam Cooke, being a pop star, was a political act. By being a pop star – not a niche R&B star, but a fully-fledged pop star, one whose appeal stretched from teenage girls to their parents partying with the Rat Pack at the Copacabana – Sam Cooke was showing that a Black man could do anything.

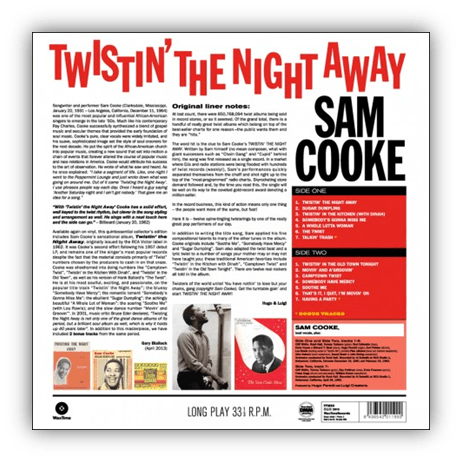

For Sam Cooke, recording an album full of nothing but songs about The Twist was a subversive act.

Then “Blowin’ In The Wind” came along. And suddenly, merely being a pop star no longer seemed enough.

Sam realized that this was the sort of thing that he should be writing… not silly songs about doing the twist and the cha-cha-cha. So he started singing his own version of “Blowin’ In The Wind”, turning it into a great big R&B rave on! And he started writing “A Change Is Gonna Come.”

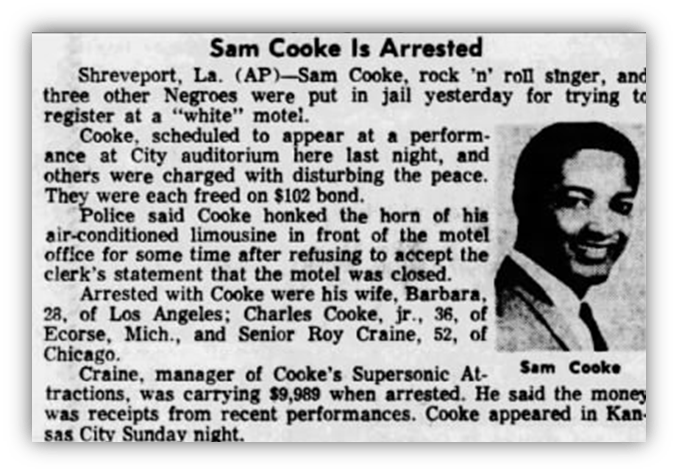

But Sam was worried. Sam realised that “A Change Is Gonna Come” would put a target on his back. He had, after all, recently been arrested.

For “disturbing the peace” aka “raising his voice at a white man” aka “raising his voice at a white man because he wouldn’t let him stay at his lousy Holiday Inn.”

That experience almost certainly inspired the “I go to the movies and I go downtown / Somebody keep telling me, don’t hang around” verse of “A Change Is Gonna Come.”

Turns out that things aren’t always great when you’re downtown.

Sam was worried enough about the power of “A Change Is Gonna Come” that he only sang it live once, then no more. Worried enough that he agreed when Bobby Womack told him that it sounded like “death.”

Worried enough that, when it was released as the B-side to “Shake”, the verse about going to the movies, and going downtown, had mysteriously disappeared.

Which is such a damn shame that everyone seems to have agreed to pretend that version never existed, and that the album version is the only version there is. At the very least, I can’t find a YouTube video of the single version to embed. Nor is it on Spotify either. You’ll just have to imagine it for yourselves.

There are people who believe that “A Change Is Gonna Come” is not about society or Civil Rights per se, but about Sam’s own inner monologue and his conscious decision to become more conscious.

To start using his profile to drop truth-bombs about society. To become more than just a pop star.

Sadly, Sam never got the opportunity to drop truth-bombs about society. Instead he found himself shot, in sordid and convoluted circumstances, in a freak incident that nobody could have foreseen.

He did however, end up becoming far more than just a pop star.

“A Change Is Gonna Come” is a 10.

Meanwhile, in Van Land:

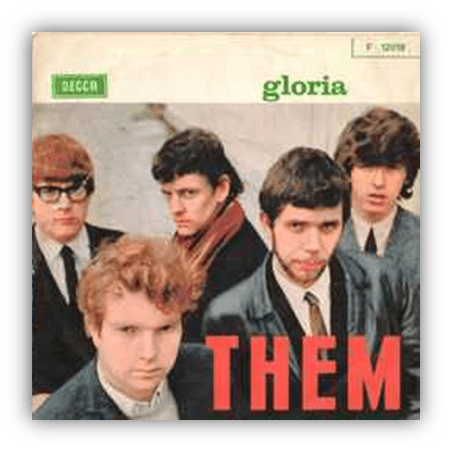

“Gloria” by Them

Had all the good band names been taken? Of course not, it was 1965, and…

- Butthole Surfers…

- Someone Still Loves You Boris Yeltsin…

- I Love You But I’ve Chosen Darkness…

- … And You Will Know Us by the Trail of Dead…

They were all still up for grabs!

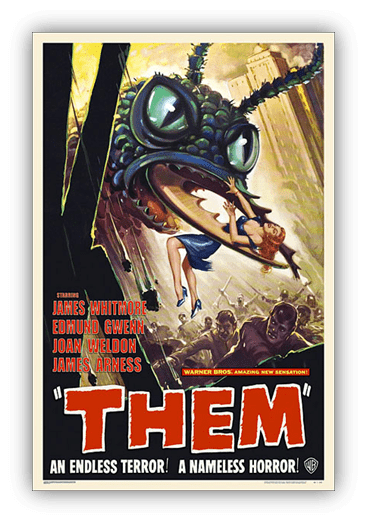

It could have been Them!, with an exclamation mark.

Them were named after a 1950s monster movie, about “A HORROR HORDE OF CRAWL-AND-CRUSH-GIANTS” – otherwise known as bugs – “CLAWING OUT OF THE EARTH FROM MILE DEEP CATACOMBS!” Turns out they’ve been radiated by nuclear goop, or something? I don’t know, I’ve never seen it.

So I guess, Them isn’t that bad a band name. After all, it allowed for advertisements raising curious questions such as “Who Are? What Are? THEM” Not to mention the puntastic album title: The Angry Young Them.

Them came to be because the Belfast’s Maritime Hotel – whose patrons, you will not be surprised to learn, included a lot of sailors – was starting an R&B night, and they needed a band to play there.

The Maritime Hotel has been described as a “spartan seaman’s hostel”, which doesn’t sound like a particularly promising place to party. Even worse it had previously been a police station.

But there’s not a lot to do in Belfast, and not a lot of buildings that haven’t been bombed, so there were soon hundreds of kids crowding into the cramped premises, to listen to Them, and their version of the blues. And to listen to Van Morrison preaching over the top of it all.

Prior to this Van Morrison had been a teenage high school drop-out who’d spent his childhood listening to his father’s record collection.

Since his father had one of the biggest record collections in Belfast – he’d lived in Detroit for a while and picked up a lot of good stuff, mostly blues, jazz and Woody Guthrie – that took up a lot of his time. It was exactly the musical education a boy might need if they planned on growing up to become Van Morrison.

Van hadn’t quite grown up by the time he wrote “Gloria.” He was still a horny teenager. I realize now that he’s been looking like The Penguin for decades it’s hard to imagine that Van was EVER a horny teenager.

But long before he wrote such 21st century classics as “Why Are You On Facebook?:”

A real, actual song, that does exist…

… a horny teenage was what he was. A horny teenager playing the blues in a Belfast pub. Reputedly turning “Gloria” into one long 20-minute jam. Building up all that sexual tension and longing, as Van tells us about his baby. How she comes around HERE! Just about MID-NIGHT!!! How she makes Van feel SO GOOD!!! How she makes him feel alright… how she comes walking down Van’s STREET!!! How she comes to Van’s HOUSE!!! – what she going to do next Van? – she’s gonna knock on Van’s DOOR!! etc

You can tell that Van is pretty excited about all of this. He makes it sound as though we are witnessing some kind of spiritual awakening… which is presumedly why he chose that name.

It’s unlikely that Van didn’t realise that crying out “GLORRRRIIIAAAA” was going to sound religious, even if you don’t follow it with “in excelsis Deo.”

Or maybe he just needed a girl’s name with a lot of vowel sounds, stacked towards the end, so that he can recite them, spell them out… Her Name Is G… L… O… R…I…G.L.O.R.I.A…!!!!!

Or at least I think the last letter is A, from the context – and also the song title – but honestly, it sounds like “OOPOOLLLAAARGGGGRRRRRL!!!!!!”

“Gloria” was the B-side, and fair enough really… hit singles aren’t supposed to sound like that; all hypnotic organs and ragged shards of guitar.

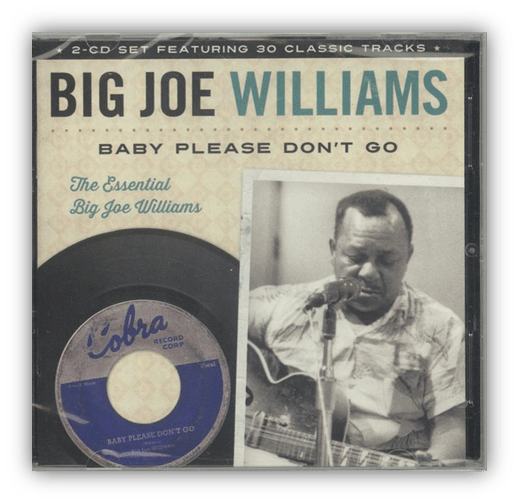

The A-side was a cover, of an ancient blues song, presumedly one from his father’s record collection: Big Joe Williams’ “Baby, Please Don’t Go” from 1935.

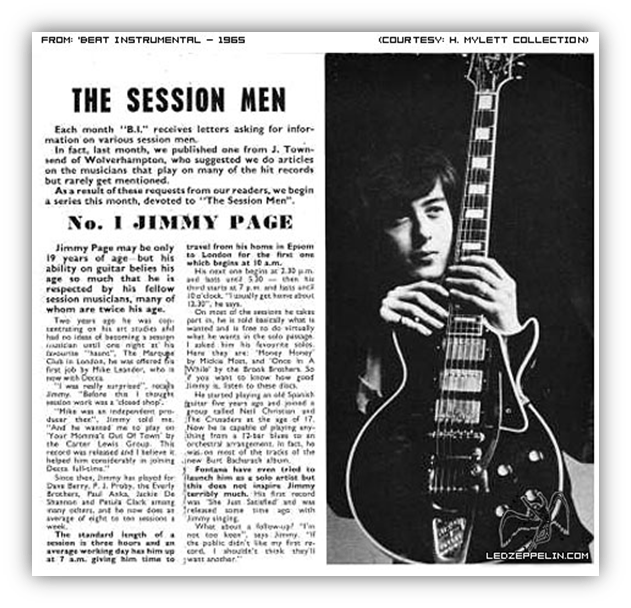

It seemed for a while that somebody would record a classic rendition of “Baby, Please Don’t Go” about once every ten years; Muddy Waters in the early 50s, AC/DC in the mid-70s… but those other versions don’t have Jimmy Page!!

Jimmy Page was on a whole bunch of records in late 1964. He is rumoured to be buried somewhere deep in the mix of “Downtown,” although nobody seems to know for sure.

Everyone is pretty sure however that he’s on “Baby, Please Don’t Go.” He’s the one playing – and possibly may even have come up with – THAT RIFF!! If so, that makes it Jimmy Page’s first ever classic riff?!?!

“Baby, Please Don’t Go” is an 8…

And “Gloria” is a 9.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

“Downtown” is just a magical song, and part of it is for the reason that Petula points out towards the end of your segment on the song. I’ve always thought the same thing. I don’t think of it really as a downer, though. But I do think the main theme is “Life isn’t easy, and sometimes you get depressed, but might I suggest a visit downtown? It will provide a temporary break from your troubles, and you might make a friend.” And you can listen to the music of the gentle bossa no-VA.

Also, I am reminded of reading a music critic’s analysis of “Downtown”. He called it the greatest record ever made. https://jackfear.blogspot.com/2003/10/greatest-record-ever-madethis-is.html

Coming hot on the heels of this from last week, ranking Petula Clark’s 20 best songs.

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2025/jan/02/forget-all-your-troubles-forget-all-your-cares-petula-clarks-20-best-songs-ranked

The lyrics in I Know A Place seem to be an attempt to reference the beat boom. Just slightly too late and in a way that comes off rather naff (as that Guardian article puts it). It could be referring to RlThe Cavern, especially as it gets in the phrase ‘a cellarful of noise’ which was the title of Brian Epstein’s autobiography from just a few months before.

It is impossible to think of Van Morrison as a horny young man. The title of their debut album sums it up well; The Angry Young Them.

Obligatory Lucille Ball / Petula Clark reference:

https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=2667290733585214&vanity=thelucylounge

Thank you…I think?

I know. I’ve got some splainin’ to do.

I have always loved “Downtown,” but it’s taken on a different aura here in Nashville. On Christmas morning three years ago, I was still lying in bed when I heard an explosion. It was loud and hard to believe, as I found out later, it was six miles away.

A disturbed middle aged man had packed his RV with explosives and parked it on Second Avenue downtown. He had mounted speakers on its outside and it continually played a voice saying to stay away because it was going to explode. It played the same message over and over for hours, and then played “Downtown” once before returning to the message. Shortly after daybreak, the RV blew up. Thanks to the repeating message, the area was evacuated and only the bomber was killed. There were no major injuries. Second Avenue is still closed and is slowly, slowly, ever so slowly being repaired.

I don’t think they ever figured out a motive, but maybe it’s right there in the lyrics. “When you’re alone, and life is making you lonely you can always go downtown.” I still love the song but it sounds more melancholy now.

I had forgotten about that. Yikes.

“Twistin’ The Night Away” is an easy 10

“Downtown” was the biggest hit for Mrs Miller and probably the best example of her inability to sing despite hitting the notes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fw07CDid0JM

Petula Clark’s appearance on Jools Holland was very moving. It’s how I remember COVID. Spending more time on YouTube. She sang “Downtown”, of course. I like surprising covers. Clark made me like Steve Winwood’s “While You See a Chance”. It’s from her last studio album Living for Today.

I like proper Van Morrison. I also like weird Van Morrison. “Ringworm” is classic weird Morrison. But my favorite deep track from The Authorized Bang Collection is “Want a Danish”.

I don’t think “Take Me Back” is in the Morrison canon but Jennifer Jason Leigh covered it in Ulu Grosbard’s Georgia.