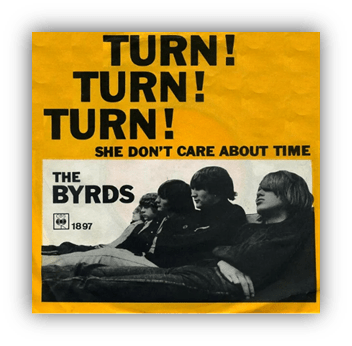

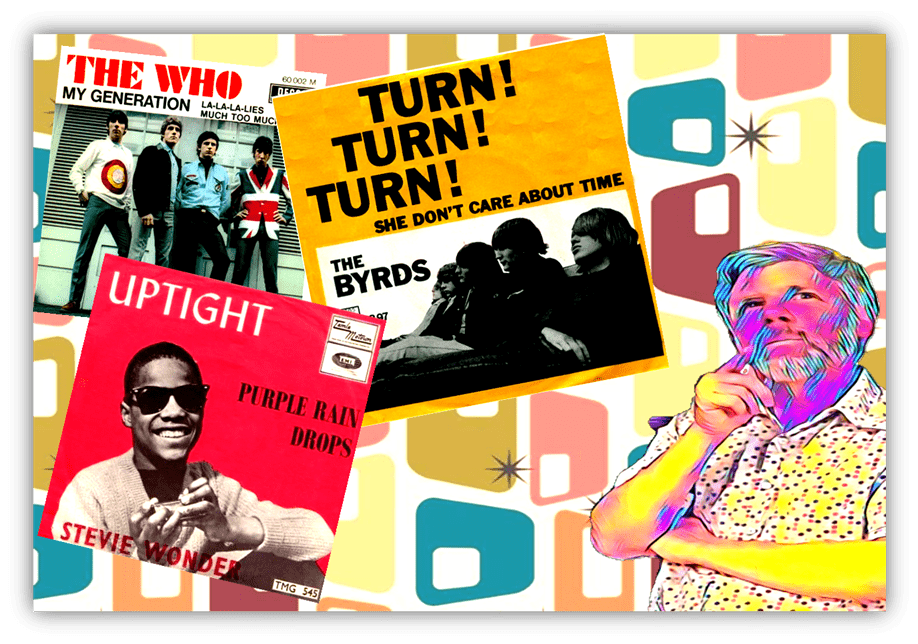

The Hottest Hit On The Planet:

“Turn! Turn! Turn!”

by The Byrds

“Turn! Turn! Turn!” is probably the oldest song I will ever cover in this column.

This might seem odd to you, given that just last week I was covering 1955. That’s 70 Years Ago! And the week before that, I was covering 1925. That’s 100 Years Ago!

But “Turn! Turn! Turn!” was written… 3,000 Years Ago! By King Solomon, in between building temples and judging court cases where he suggested sawing a baby in two (he was joking).

King Solomon wrote quite a lot of The Bible.

- He wrote The Book Of Proverbs, which is exactly what it sounds like.

- He wrote The Song Of Songs, which is apparently a book of erotic verse (I’m pretty sure my local Catholic priest never read any passages out from that!).

- And he wrote Ecclesiastes:

A book that attempts to answer the question:

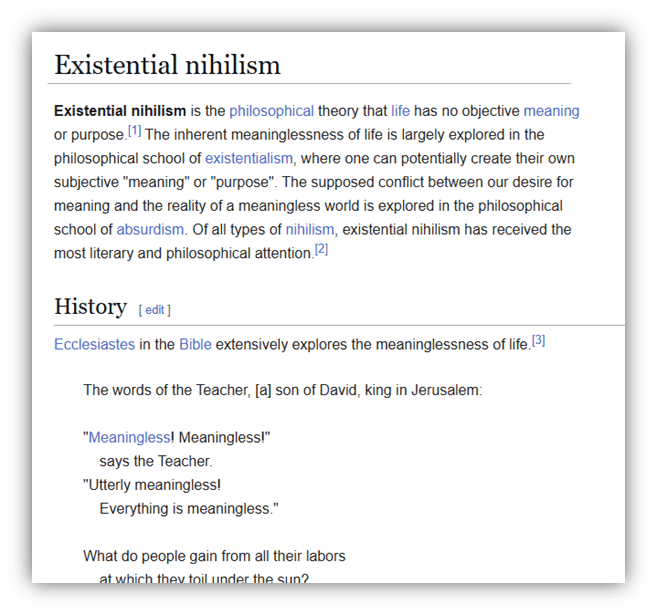

“Meaningless! Meaningless!! All is meaningless!!!… What profit hath a man of all his labour which he taketh under the sun?”

Thereby inventing existential nihilism.

(It’s actually quoted in the Wikipedia page on “existential nihilism,” so I’m not just making it up)

In Chapter 3 however, we come across this familiar passage:

“To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven:“

“A time to be born, and a time to die;

A time to plant, and a time to pluck up that which is planted;

A time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up;“

“A time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance;

A time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together;

A time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing;“

“A time to get, and a time to lose;

A time to keep, and a time to cast away;

A time to rend, and a time to sew;“

“A time to keep silence, and a time to speak;

A time to love, and a time to hate;

A time of war, and a time of peace.”

I tend to feel that, purely as a piece of literature, The Bible is a bit over-rated. Greatest Story Ever Told?… Bah… sure, it starts off strong, with Adam & Eve, Cain & Abel, Noah & The Ark, “Joseph & His Technicolor Dreamcoat, Moses In The Bullrushes, The Burning Bush and The Parting Of The Red Sea… But that’s all over by about halfway through the second season. After that, it really starts to drag.

But I have to say, that “to everything there is a season” bit is pretty good.

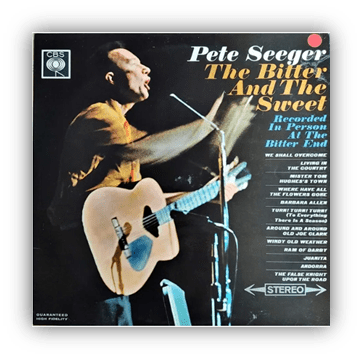

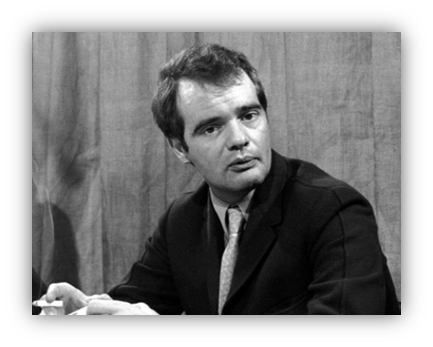

Pete Seeger certainly thought so.

Pete Seeger had been leader of The Weavers:

A folk group that – for a second at least – became the most popular group in the world in the early 1950s, turning “Goodnight Irene” into a smash. Not to mention “On Top Of Old Smoky.” All before being taken down by Joe McCarthy and blacklisted for being Communists… so long, it’s been good to know yah.

By the end of the 1950s, Pete had become something of a folkie elder statesman. Also a protest song writer.

At one point – in 1959 – his publisher got shirty, complaining that nobody wanted to buy Pete’s silly protest songs, couldn’t he write something everybody could like? And so, since “The Bible” was in the public domain, took the lyrics from Chapter 3 of Ecclesiastes, added six words:

“I swear it’s not too late”

(America wasn’t in any war worth mentioning at the time, so I guess it was just about The Cold War in general?) and, as he put it, “one more word repeated three times.”

And that was it. He gave it to his publisher. His publisher appeared to be happy. Pete also may have come up with the exclamation marks.

Certainly they appear on the artwork of his 1962 live album.

Pretty much all of the versions that would come in its wake :would also feature exclamation marks. None of them sound exciting enough to justify them. Even The Byrds’ version, the peppiest of the languid bunch, doesn’t sound like the kind of song that requires exclamation marks.

Given that The Byrds are considered by many critics to be one of the Most Influential Bands Of All Time:

- For perfecting the jangle guitar sound…

- For having its members constantly pop up in other influential bands (Crosby, Stills & Nash, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, the Flying Burrito Brothers)…

- For recording “8 Miles High”…

It’s remarkable how deeply un-cool their pre-Byrds backgrounds all were.

Gene Clark, for example, had been in the New Christy Minstrels:

Who named themselves after an old 19th century minstrel group – The Christy Minstrels.

And on this single, on which Gene – and Barry “Eve Of Destruction” McGuire – sang back-up, they provided the theme song for a movie set during the Civil War. Despite actually being a new song, it sounds far older than “Turn! Turn! Turn!”

Jim McGuinn – he’d later call himself Roger, which was his middle name – had studied folk music, at a dedicated folk music school – the Old Town School of Folk Music – in Chicago. before making the inevitable move to the bright lights of New York and the dimly lit coffeehouses of Greenwich Village.

There he was being paid $35 a week to write folk songs for fading teen-pop-star and wannabe crooner Bobby Darin:

Who had hatched a foolhardy plan to jump onto the folk-music wave.

It didn’t take.

At the same time Jim was playing guitar on folk records, including on Judy Collins’ version of “Turn! Turn! Turn!” He also played on the Limelighters version, although they just called it “To Everything There Is A Season.” It’s fair to say that Jim knew the song quite well.

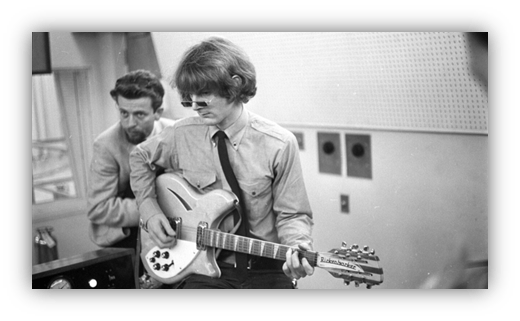

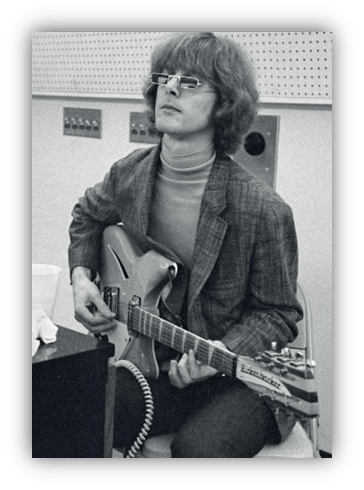

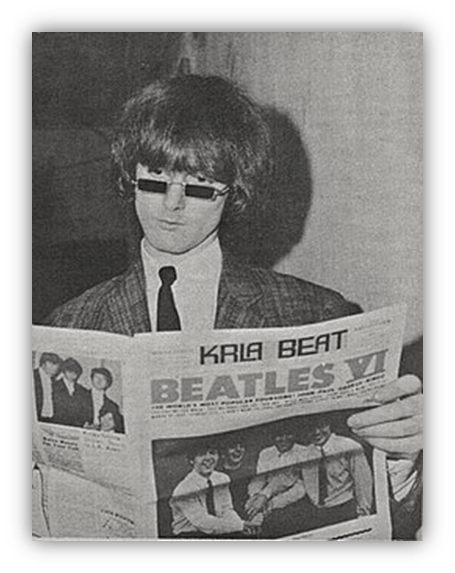

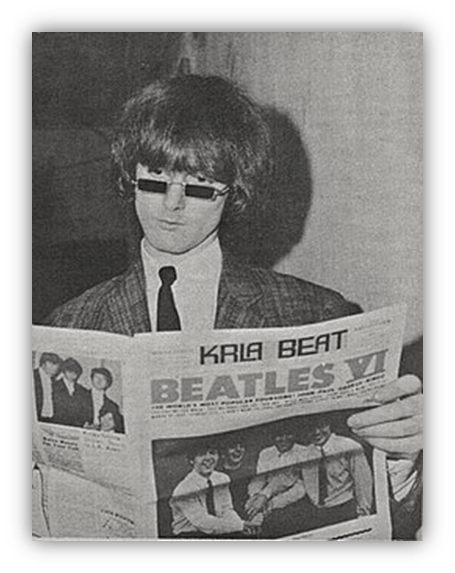

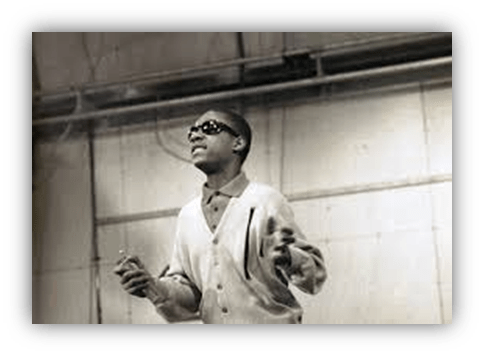

Jim probably seemed a hell of a lot cooler once he got himself a pair of the world tiniest rectangular sunglasses that Internet sleuths have concluded were probably “Pat Boone” branded sunglasses manufactured in Japan.

Then Jim, like everybody else, got obsessed with The Beatles. He got a Rickenbacker like George. He grew his hair… even longer than they did. He found himself in L.A. playing at a folk club imaginatively titled The Folk Den – it would soon become the Troubadour, a much better name – where he sang Beatles songs. And formed a duo with Gene, basing their act on The Beatles associated duo, Peter & Gordon.

At some point David Crosby…

(Who had not yet grown his patented facial hair and looked like a cheeky little monk… )

– heard them rehearsing on a stairwell and started singing harmonies along with them. David also mentioned he knew someone with a studio they could use for free… so he was in)

Then they all went to see “Hard Day’s Night” together, after which they decided that was what they wanted to do with their life.

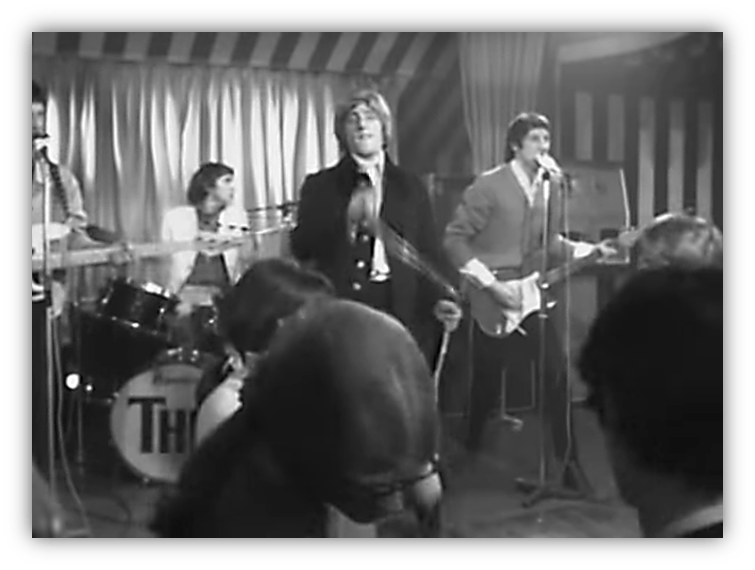

When it came to choosing a band name, they ripped off The Beatles again, by going the incorrectly- spelling-an-animal route and calling themselves The Byrds.

The Byrds managed to effortlessly combine every second trend that was running through pop music at the time:

Beatlesque guitar jangles, Beach Boys-esque harmonies, Dylan-covers, and the unmistakable sense that their records were made in California. Not necessarily made by themselves however:

Their first Number One hit, their cover of Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man” famously featured mostly the sounds of The Wrecking Crew (also a bit of Jim on guitar). The best review of the song came from Dylan himself: “Wow, you can dance to that!”

Well, I guess you can. Sort of. You can shuffle your feet a little at least, which was not something you could do to most Dylan songs yet.

“I’m not sleepy,” The Byrds sang, although it genuinely sounded as though they were. Their vocals would again sound sleepy on “Turn! Turn! Turn!” and once again, typing those exclamation marks feels wrong.

It’s not like The Byrds couldn’t sound like an exclamation-mark- worthy band when they felt like it.

Between “Mr Tambourine Man” and “Turn! Turn! Turn!” they released the Gene-penned and catchy-as-Hell “I’ll Feel A Whole Lot Better.”

An argument could be made that they invented power pop with that one. It may be the best thing they ever did. But nobody seemed to care about The Byrds when they weren’t making folk covers you could sort of shuffle your feet a little to.

Back to finding a folk song to cover, then.

Initially the plan was to cover Dylan’s “It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue”, but that would’ve been too obvious. They’d already released two Dylan covers as singles in row.

(“I’ll Feel A Whole Lot Better” had actually been a B-side, the A-side had been a cover of Dylan’s “All I Really Want To Do”)

So they were in danger of just becoming “that Dylan tribute act.” In the end “All I Really Want To Do” flopped, although that was mostly because it was competing with another version, by Cher. Nobody should ever try and compete with Cher.

So “Turn! Turn! Turn!” it was, then.

If you were not aware of its Biblical origins, “Turn! Turn! Turn!” does not sound especially old.

Sure, it contains words that people do not use very much anymore, or even in the 60s. Such as “rend.” And sure, it mentions activities such as casting stones, which nobody does anymore, except metaphorically. And gathering stones together (so you have a supply of stones handy for the next time you need to stone someone?)

But The Byrds weren’t trying to sound like David playing secret chords on his harp.

They were trying to sound like The Beatles playing that secret chord at the beginning of “Hard Day’s Night.”

When they sing though, The Byrds sound reassuring, as though calmly coaxing someone from jumping off a cliff… or a country from jumping into Vietnam… but there’s an energy to it. This one you can dance to, particularly during the “a time of” bits… where the drumming gets all jazzy.

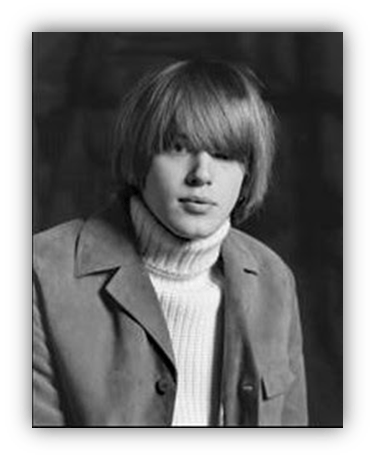

Not bad for a drummer who was only hired because he looked like Brian Jones, thereby allowing The Byrds to look like both The Beatles and The Rolling Stones in the one band.

It’s not enough to earn exclamation marks, but The Byrds’ version of “Turn! Turn! Turn!” is groovier than anything King Solomon could have imagined.

“Turn! Turn! Turn!” is an 8.

Meanwhile, in Mod Land…

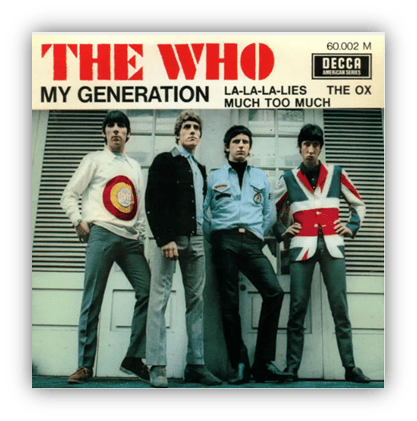

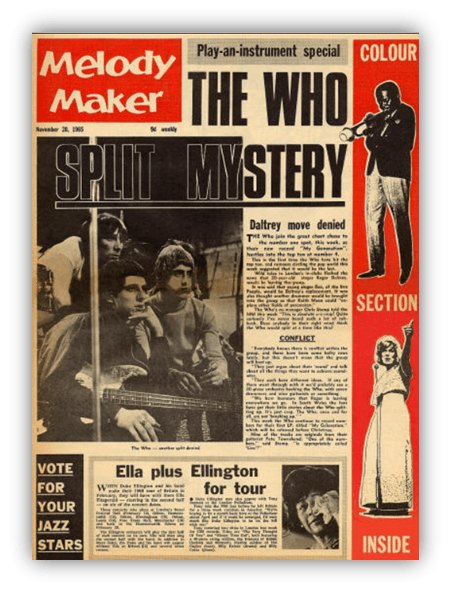

It’s “My Generation” by The Who

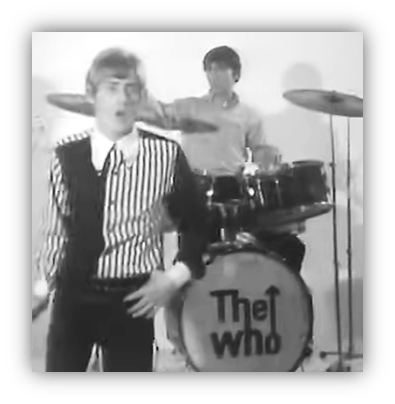

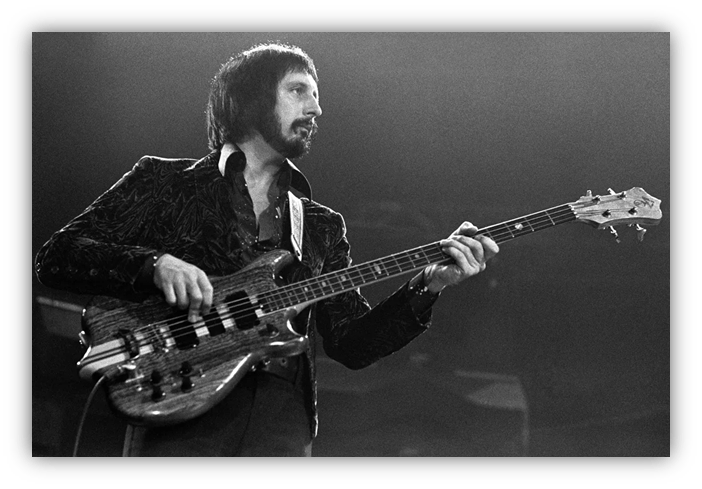

The Who were – probably – the loudest band in Britain.

They described themselves as “Maximum R&B.” That seems weird now, but it made perfect sense back then.

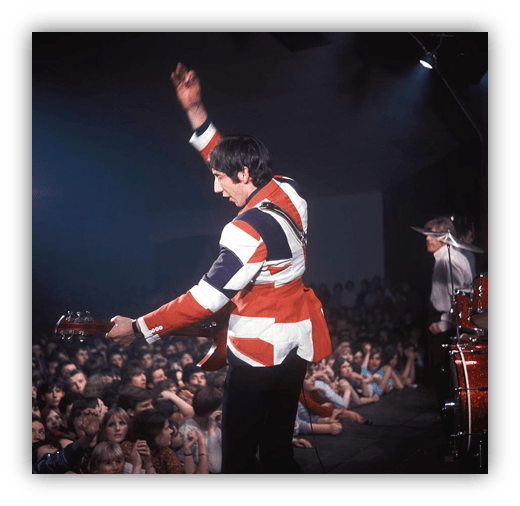

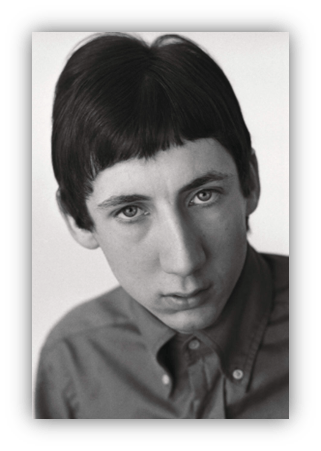

Everything about them was loud, including the Union Jack that Pete Townshend liked to wear as a jacket.

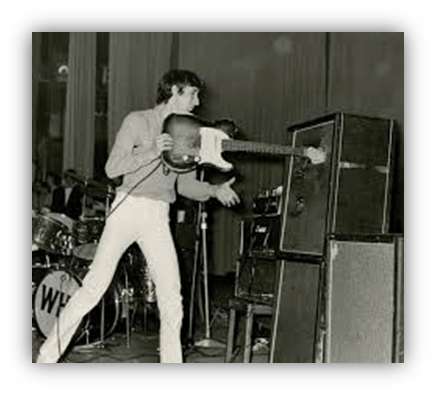

A lot of this was due to Pete’s love of amassing larger and larger speakers and then making far-out noises with his guitar to make amassing such a collection worthwhile. Many of those far-out noises were the result of his smashing his guitar and other innocent bystanding equipment into pieces. Also from playing slide-guitar with his microphone stand.

Also from shoving his guitar right into the horn of his speakers.

Also from shoving his guitar right into the horn of his speakers.

(A speaker needs to be pretty big for you to be able to shove your guitar into its horn). He also had this thing where he’d hold his guitar like a machine gun, and make it make machine gun noises.

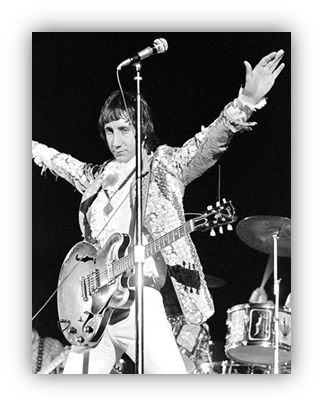

And he had a move he liked to call “The Birdman” – raising his arms up and out whilst his guitar just wallowed in feedback.

Whilst Pete was doing all of this, the audience would largely be ignoring him.

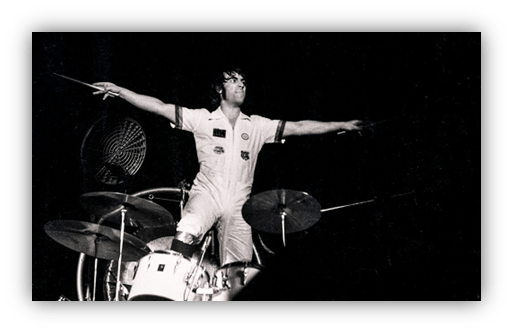

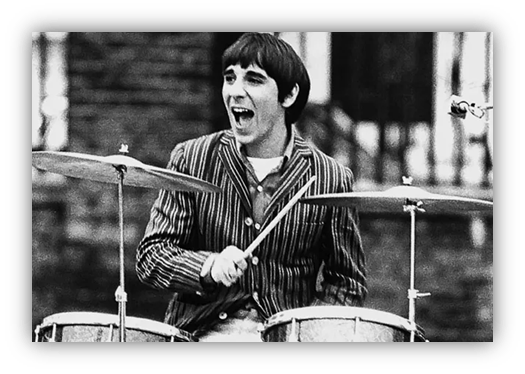

That’s because the audience were too busy staring at Keith Moon on the drums.

The fact that the audience was staring at the drummer at all was new. Drummers were traditionally not to be stared at. The drummers in most bands could be safety ignored. They rarely did anything interesting.

Keith Moon on the other hand, drummed like – and looked, and by all accounts was – a man possessed.

He also juggled his drumsticks, which, given everything else that he was doing with them, looked especially impressive.

Rock’n’roll drumming can be divided into a pre-Keith Moon and post-Keith Moon era. It’s truly weird watching pre-Keith Moon drummers; even the more animated ones, like Ringo, seem oddly nonchalant (compare Keith to the half-hearted tapping of Byrds’ drummer Michael Clarke, even at his jazziest)

Keith, on the other hand, goes at it like an animal.

There is a reason his art teacher had previously described him – in a school report – as “idiotic”, thereby establishing the cerebral reputation of every drummer that would come in his wake. And then, at the end of the gig, as if in competition with Pete, he’d trash his drum kit.

This should give you a rough idea what they were like:

So… loud band… lots of feedback… a maniac for a drummer… all the rebellious rock band cliches were there… they even made sure they had a proper lighting show, which was pretty much unheard of at the time… what was missing?

Swearing, I guess.

“Why don’t you all just f..f..f…. ade away” Roger Daltry stutters, in what may have been the closest thing to the f-word ever to feature on a hit single. The BBC banned it for a while. Not because they thought he was swearing, but because they thought he was making fun of stutterers.

Turns out, Roger wasn’t initially almost-swearing. Neither was he intentionally making fun of stutterers. All of those stuttering bits… the “My.. My.. My… G,g,g-eneration” bits – were meant to sound like a Mod on uppers. The BBC probably missed that reference. So, most likely, did most of their fans.

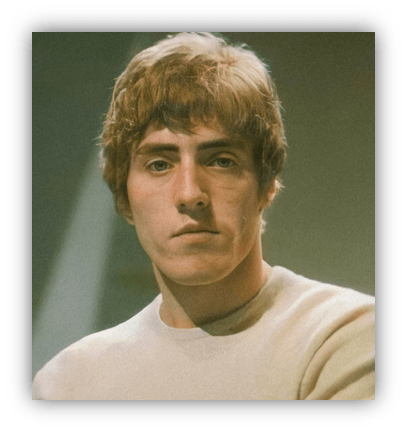

Roger Daltry looked like the kind of guy who might be tempted to swear on a hit single.

There’s a reason that the top comment for this photo on Instagram is “always looks like he wants to kill somebody”

Turns out this wasn’t entirely an act. The Who would have band arguments that ended in Roger punching other members in the schnoz.

Probably Pete’s, since it was pretty hard to miss.

Roger was so violent, so prone to punching other band members in the face, that he was temporarily kicked out of the band.

It was after they’d recorded “My Generation”, but before it had become a hit. Keith was supplying Pete and John – the bass player – with amphetamines before a show. Roger wasn’t into that, because that would mean they’d play too fast and it would sound shit. So he flushed the pills down the toilet. So Keith came at him with a tambourine (apparently more dangerous than it sounds). So Roger punched him in the face. So they had a band meeting and kicked Roger out of the band.

But then “My Generation” became a hit, so they had to accept him back.

Roger liked to attribute this violent streak to the fact that he grew up in a tough working-class environment; that he was born with a plastic spoon in his mouth. They all were to a certain extent, but Roger was the most. He’d been expelled from school at 15. He’d worked on building sites. He’d hung out with a gang of toughs.

Not just working class, but decidedly masculine.

The Who were probably the first band to incorporate the male symbol into their band logo.

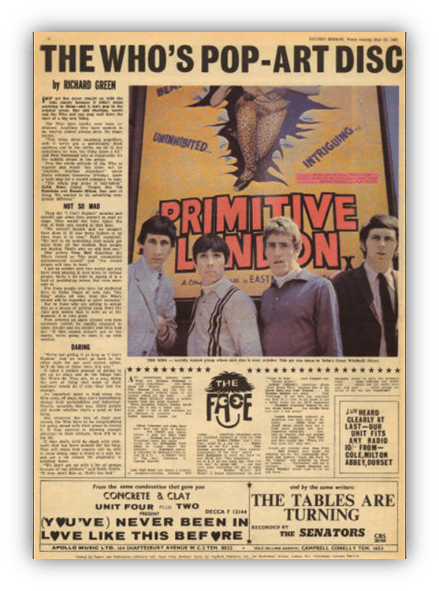

All of which makes it odd that, when they were initially gaining media attention, it wasn’t necessarily for being loud, or violent, or their toxic levels of masculinity… it was because Pete couldn’t stop banging on about how they were “pop-art”… he simply couldn’t stop saying things like “we stand for pop-art clothes, pop-art music and pop-art behavior..”

Rock stars talk a lot of rubbish don’t they?

“Well,our next single is really pop-art.” Pete said, almost certainly referring to “My Generation”.

“I wrote it with that intention. Not only is the number pop-art, the lyrics are ‘young and rebellious’ It’s anti-middle age, anti boss-class and anti-young married. I’ve noting against these people really – just making a positive statement.”

“The big social revolution that has taken place in the last five years is that youth, and not age, has become important. Their message is: “I’m important now I’m young, but I won’t be when I’m over 21.’ ”

Pete was 20 at the time of this quote. 20 when he released “My Generation.”

The whole pop-art idea probably wasn’t Pete’s. It was their new manager’s, Kit Lambert.

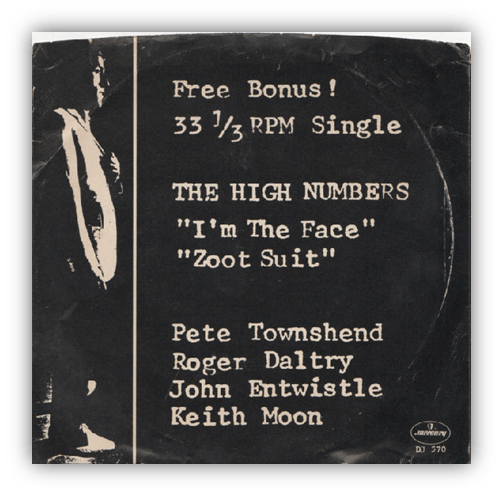

This was after their previous manager – Peter Meagan – had the idea of turning them into the ultimate Mod band:

Mods being the best dressed subculture in Britain at the time.

Their first single – under the moniker The High Numbers – was virtually an undisguised, shameless bandwagon jumping single named after Mods’ favourite article of clothing, the “Zoot Suit.”

To make sure they kept to the ‘We’re A Mod Band” brief, Peter wrote the song himself.

The B-side was even more blatant. In every Mod community there would be one Mod who was manifestly the most popular, the one who set all the trends.

That Mod was called “The Face.”

So the B-side to “Zoot Suit” was titled “I’m The Face.”

Nobody bought the record – other than Peter, who bought a whole bunch to try and get it into the charts – not even the Mods. It turns out that Roger Daltrey was not, in fact, The Face.

So The Who had to come up with a different plan. And get a different manager.

They got Kit Lambert, who wanted to make a movie about them. Or at least he wanted to make a movie about a band, and The Who, what with their trashing their equipment on stage act, seemed like a good band to make a movie about.

Kit had previously made a documentary about an exhibition into the Amazon.

Where an uncontacted tribe killed the explorer, Richard Mason, the star of the movie, after which Kit had been arrested for his murder.

Managing a rock band probably seemed like a safer option.

Sadly, The Who movie never came out – neither, as best as I can tell, did the Amazon movie, probably because the star was dead – but The Who became famous anyway.

Now, since Pete Townshend had at least been to art-school – and wrote all the songs – Kit decided to mentor him, teach him about “pop art” and set him up around the corner from Buckingham Palace.

It turns out that Pete owned a hearse.

It was the only car he could afford to drive. And he parked it on the street.

The Queen Mother saw the hearse, and it reminded her of her dead husband. His funeral procession had included a hearse that looked very much the same. And so she had Pete’s hearse towed.

Pete was pissed off, and that’s when – so legend has it – he wrote “My Generation.” God Save The Queen Mother. She’s got into a bother. She towed my hearse car. She wouldn’t tell me where it are.

As a record “My Generation” is a raucous ruckus.

The bass guitar breakdown, dead-simple because John Enthwhistle, already forced to give up lead guitar because his fingers were so big, found that they were still too big to play his favourite bass without breaking the strings.

It’s as though every single member of The Who was so badass that their instruments couldn’t handle being in the same room as them.

Then Keith goes apeshit on the skins towards the end… it’s probably the most apeshit anybody has ever drummed on any hit single before. And Pete makes a whole lot of noise on guitar.

As a song however, as an anti-authority generational anthem, “My Generation” feels a little obvious… it’s probably the most self-conscious generational anthem ever recorded.

Perhaps that’s because every second anti-authority generation anthem written since then has basically just been a rewriting of it.

But “why don’t you all fade away, don’t try to dig what we all say, I’m not trying to cause a big sensation, I’m just talking about my generation” is extremely rudimentary stuff. Which of course is the point.

You don’t expect poetry from someone prone to punching people in the face. I think I’m just mad because they say they’re talking about their generation, and then they don’t actually say anything. Which, again, I guess, is the point.

You don’t expect considered political commentary from someone prone to punching people in the face.

But instead, they just sing the same two verses a second time.

Presuming that one of the things the olds say to “put us doowwwwnnn” is that kids these days are too lazy to write proper songs, “My Generation” might just be an own goal.

Is “My Generation” “anti-middle age, anti boss-class and anti-young married”? Is it really? How can you tell?

For all of that, at least it’s not “Zoot Suit.”

“My Generation” is an 8.

Meanwhile, in Motown Land…

It’s “Uptight (Everything’s Alright)”

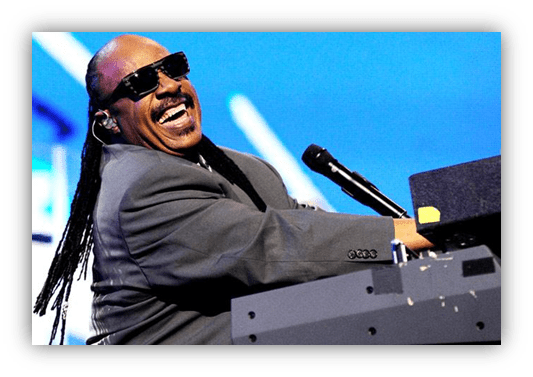

by Stevie Wonder

Stevie Wonder’s career was not alright.

Stevie Wonder’s career was in trouble.

Stevie Wonder was 15 years old, and it looked as though his career was over. Word heard through the Motown grapevine was that Stevie Wonder was about to be dropped.

Was Stevie Wonder worried? Judging by this evidence, he was not. Judging by this evidence, he was still radiating positivity.

Then again, radiating positivity is the Stevie Wonder way.

Prior to “Uptight”, Stevie Wonder was mostly famous for being Little Stevie Wonder, a baby Ray Charles impersonator who held the record for the youngest ever artist to have a Billboard Hot 100 Number One, with “Fingertips Part 1 & 2”, a record that might also hold the record for being the oddest Number One of all time. Although obviously, there’s a lot of competition there.

“Fingertips” was not really a song, but a live concert performance with a bunch of “EVERYBODY, SAY YEAH!” bits, a whole lot of blistering harmonica solo, and that part where Stevie finishes, is guided by his minder off to the side of the stage, but then surprises everybody, not least the band – who clearly hadn’t been paying attention for Stevie had just spent an entire verse telling everybody this was exactly what he was planning to do – by popping back onto the stage again for another blistering harmonica solo!

A few years later, Stevie was still impossibly young, but at least he had dropped with Little from his name.

Unfortunately, his voice was also dropping, and Motown was worried Stevie was about to lose his pre-pubescent charm. Motown didn’t know what to do. They did not know how to market Stevie anymore. They had known how to market a pre-pubescent blind boy – as a novelty act – but they had no idea how to market a horny teenage blind boy.

Even before his voice had broken, Little Stevie’s chart fortunes had been in freefall.

It was as though “Fingertips” had been a happy accident – which it basically had – one that could never happen again. Whatever it was that had made “Fingertips” special, “Happy Street” did not have it. Even after being featured in “Muscle Beach Party,” nobody liked it enough to buy.

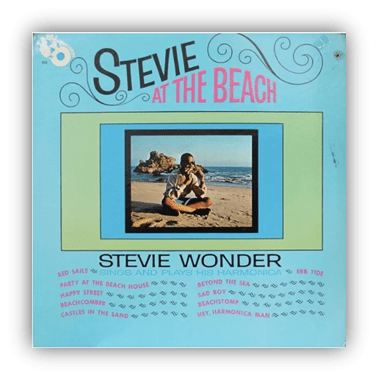

Flailing around for a new gimmick to salvage Stevie’s career, Motown came up with the “Stevie At The Beach” album, an attempt to catch the surf-music wave that had already crashed a year before.

Truly, they did not know what they were doing.

It was time for Motown to count their loses and put all their efforts into The Supremes once more.

If Stevie had been feeling anxious about the likelihood he was about to be dumped, “Uptight” shows no sign of it. “Uptight” sounds like pure swagger, pure confidence.

Even when on the precipice of becoming a one-hit loser, Stevie sounds like a winner.

“Uptight” sounds like a victory lap. “Uptight” sounds as though it knows just how good it is, and feels certain that the whole world would soon know as well.

“Uptight” gave the world it’s first inkling that Stevie Wonder was a musical genius in the making.

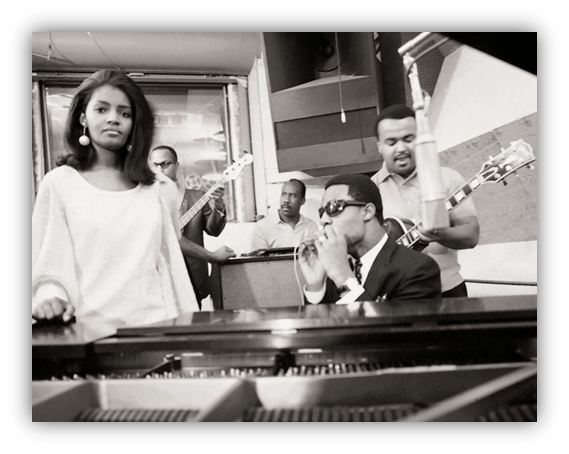

For although Stevie didn’t write all of “Uptight”, he came up with all the important bits: the title, and, most crucially, the horns, rumoured to have been based on “Satisfaction” by The Rolling Stones who Stevie had been touring with.

And sure, okay, I guess I can hear that. “Uptight” is what “Satisfaction” could have been if Mick could have got no satisfaction (or could have got satis… oh, you know what I mean…)

So, the horn section and the chorus… that’s basically the whole song, right?

The story, of Stevie being a poor man’s son from across the railroad tracks, no football hero or smooth Don Juan… all that came from Sylvia Moy:

Who would go on to help Stevie with a whole bunch of songs – also “It Takes Two” – and who, since she hadn’t time to translate the lyrics into braille, sang them to Steve as he was recording – feeding Stevie each line a couple of seconds before he sang it.

This can’t possibly be true, can it? That sounds like a terrible way to make a record.

Then again, maybe that’s why Stevie sounds so excited singing the words; they were totally fresh to him!

So… poor man’s son from across the railroad tracks, no football hero or smooth Don Juan… Stevie’s girlfriend, on the other hand,

“The right side of the tracks she was born and raised

In a great big old house full of butlers and maids”

“Uptight” is basically a poor boy falling in love with a rich girl song. Like so many other songs. Like pretty much every teenage rom-com.

Like The Great Gatsby.

Poor-boy-falling-in-love-with-rich-girl is a timeless theme.

“Uptight” might be the best poor-boy-falling-in-love-with-rich-girl pop moment ever… better that Gatsby, better than Dirty Dancing, better than Titanic, better than Aladdin, better than Notting Hill, better than The OC, better than Gossip Girl…

Or at the very least the easiest to dance to…

(“Common People” doesn’t count because, although it features a rich girl and a moderately-middle-class boy, Jarvis is not in love with her, but merely tolerating her so he can get free rum & Coca-Colas)

You could hear “Uptight” a million times and not notice the class-warfare aspect, what with being so carried away by the drums – although not as apeshit as Keith Moon, the drum rolls on this thing are like next-level! – and the horns, and simply the whole sensation of Stevie sounding on top of the world… and when Stevie’s on top of the world, everything’s alright… uptight… clean out of sight!

Stevie himself gets a little carried away towards the end… “HA HAHAHAHA YEAH!!!” and rightfully so.

Now THAT’s what I call “Maximum R&B”!!

“Uptight (Everything’s Alright)” is a 10!

P.S.:

The title – “Uptight” – possibly seems a little odd, yes? I mean, “uptight”, that means a neurotic person, right? But back then, on the streets, “uptight” was slang for, well, “everything’s alright.” Apparently the other definition – that of a repressed person – wouldn’t emerge for a couple of years, when the hippies made it up.

P.P.S.:

And just to clarify, despite what the cover artwork might have you believe, Stevie Wonder did NOT write “Purple Rain” in 1965… it’s a very different song called “Purple Rain Drops.”

And presenting the Official It’s The Hits Of November-ish 1965 Playlist…

Featuring The Who, The Strawberry Alarm Clock, the Lovin’ Spoonful, The Human Beinz, The Velvet Underground… and The Byrds of course… it’s a very 60s rock party playlist, from “Turn, Turn, Turn” to “Run, Run, Run”.

https://open.spotify.com/playlist/5dmiXvjcLBF0Ol5bSJavRJ?si=9eb2f24debec426d

On the country side of the tracks, one of the most “of its time” songs ever to top that chart was charging toward the top.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dSOvjgTLqOE

Fun fact: Country legend Kitty Wells sings backup on this song.

Clicking on today’s article and immediately finding DJ Professor Dan discussing the bible was somewhat concerning, as in, “where is he headed, and do I want to be in this car?” But as someone who considers Ecclesiastes 3:1-15 to be a stone-cold jam, I was glad to see you seemed to appreciate it as well. That’s about all I have for today.

I have a hard time imagining Bob Dylan dancing, though he’d probably dance The Shrug well.

“My Generation” is indeed an 8, but the bass solo is a 10.

You’re right. I never caught on to the poor-boy-rich-girl storyline. You just made a great song better for me.

I had no idea of the origins of Turn! Turn! Turn! I wasn’t brought up with religion, are there any other songs that so blatantly crib from the bible?

And just typing the title it feels very wrong adding the exclamation marks. If you’re setting the bar that low for excitement where do you go when you actually having something worth exclaiming about?

I’d also never considered the negative connotation of the word Uptight is at odds with the joyfulness of the song. I’m learning things today.

Somebody somewhere wrote something for a bunch of somebodys some time ago, re: exclamation points in late ’65 pop music:

I wonder if ‘Turn! Turn! Turn!’ holds the record for most exclamation points in the title of a song during the rock era, or just for no. 1s. Speaking of exclamation points, the Beach Boys, whose new single ‘The Little Girl I Once Knew,’ is currently rising on the charts, put together a string of three albums in a row in the mid-’60s with exclamation points: The Beach Boys Today!, Summer Days (and Summer Nights!!), and Beach Boys Party!. Keep ‘em excited, demanded Murry Wilson, just before threatening Brian with a mic stand. Luckily, we didn’t get Pet Sounds!.

are there any other songs that so blatantly crib from the bible?

1970’s “Rivers of Babylon” by Reggae artists The Melodians was taken word for word from Psalm 137. The song was covered by Boney M in 1978, and this version went #1 or charted very high practically everywhere but in the U.S. It’s fun to imagine people disco dancing all over the world to a song of lament ripped right out of the Bible. There is also a 3 part round that incorporates a shorter passage from the same text. It was covered by Don McLean, as “Babylon” on his American Pie album. It’s haunting and great.

The oft-discussed “The Lord’s Prayer” by Sister Janet Mead, charting at #4 in the U.S. and #3 in Australia, is a rock setting of the common Christian prayer, The Our Father, the words of which come directly from the Gospel of Matthew 6:9-13.

The words to the verses of “40” by U2 all come from Psalm 40, but the chorus is a derivative of Psalm 13 (“How Long, O Lord?”), but the texts work well together, as they both come from a place of crying out to God and trusting in God’s deliverance amidst hardship.

I would say those are examples on par with “Turn! Turn! Turn!” There are many other songs that to a lesser degree will borrow their title or snippets of lyrics from Bible passages. “Fight the Good Fight” by 80s Canadian prog-ish rockers Triumph would be a fine example.

I included only songs that had mainstream popularity, not songs from the genre of Christian Contemporary, of which there are scads of examples, as that would be like shooting fish in a barrel.

Thanks rb! I know there are plenty of songs with biblical references but you came through with the ones that take it to extremes.

I’m well aware of both those versions of Rivers Of Babylon. Boney M were huge here and The Melodians version is on The Harder They Come soundtrack that I own. Should have got that one.

Looked it up to see who is credited as songwriter. Boney M credits two members of The Melodians along with the man behind the M; Frank Farian and George Reyam. Easy pickings for them, I guess cribbing from an ancient text there’s no danger of copyright issues.

Interestingly enough, there were copyright issues with the music portion of “Rivers of Babylon”. Farian didn’t initially give credit to the songwriters from the Melodians and on subsequent pressings that was rectified.

Tangentially related:

https://youtu.be/qWzpJoaZYlo?si=TGm0WE4wHSBABOuU

I obviously went to the wrong church.

Not to yuck on someone elses yum, but yuck. And assuming the Boss didn’t approve it, YouTube’s algorithm should have sniffed that out for copyright violation within seconds. I’m really surprised it hasn’t been removed. Yes, I’m a killjoy on multiple levels.

Actually, The Who did get the actual f-bomb onto the charts in 1978. “Who Are You” clearly had the word in the chorus. I have heard that it was played on the radio because the word was buried so deep that the censors didn’t catch it. I don’t know if that is true, but I do know that every teenager in America heard it. And we loved it. IT was NOT buried in the lyrics when we sang it.

Daltrey went back into the studio and re-record that line replacing the f-bomb with “hell” for the radio version. It was one of the shorter recording sessions ever and some stations preferred the original.

All of the stations in Louisville and Indianapolis played the original version. I have actually never heard the “clean” version that I am aware of.

The current Walmart commercial which uses “Who Are You” decidedly does not drop an F-bomb.

That always amazed me. It seemed that this particular song got a pass for some reason. You would always wait for it and then think, “wow, on the radio?”

It always surprised me, too. But I loved it.

After “Uptight”, my favorite poor boy who isn’t good enough for rich girl song is Frankie Valli’s “Dawn(Go Away)”. I hear the advent of Morrissey at the 1:32 mark. Three seconds of frustrated falsetto without words before the chorus. Valli knows it’s over.

I’m right with you. Their best song. Much more raw pain and emotion in those vocals than any of their other hits by far.