The Hottest Hit On The Planet…

It’s “The Yellow Rose Of Texas” by Mitch Miller

Mitch Miller.

The man responsible for more of the worst music of the 1950s than anyone else, decided that it was time to get out from behind his Artists & Repertoire desk from which he ruled the pop charts like a fascist dictator, and get his name in Big Bold Print on the label of a Big Bold Hit Record.

You can do that when you are basically running Columbia Records, the biggest record company on the planet. A position that you hold because you have found the Golden Rule for hit single-making success in the 1950s:

“It is not possible for a song to be too cheesy for the American people.”

There may have been other movers and shakers in the music industry who also understood this, but they possessed something that Mitch Miller lacked: shame.

And Mitch Miller possessed something that they lacked: the kind of twisted sensibility that allowed him to take one look at the pop landscape of the early 50s, one look at all the happening things happening in the emerging wave of rock’n’roll and think “nup, the American people are having none of that: what they really want is wall-to-wall harpsichords and French horns.” And incredibly, nine times out of ten, he was exactly right.

At his peak, in the first half of the 50s, Mitch was the guy who chose the pop stars, decided upon their image, chose the songs that they would sing, and the zany instrumentation that they would sing along to.

It was Mitch who decided that Frankie Laine, an Italian-American jazz singer from Chicago, whose father had been Al Capone’s barber, and who had previously been a Nat “King” Cole impersonator, would make a far better cowboy impersonator. He was right.

- Mitch was the guy who decided that Tony Bennet should sing country songs.

- That Rosemary Clooney should pretend to be Italian.

- That Jimmy Boyd should sing “I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus.”

Then there was Guy Mitchell, who was such a guinea pig for Mitch’s vision of covering the charts in cheese, that Mitch named him after himself! By 1955 Guy Mitchell already had six U.S. Top Ten hits, two UK Number Ones – and probably would have had more if the UK charts had started before 1952- and yet his biggest hits were yet to come.

“Success,” as a newspaper report put it in 1957, “is a trademark of Mitch Miller.”

Although, most people would have nominated his pointy beard, which made him look like a beatnik Communist.

Judging by his recorded output, Mitch Miller was the polar opposite of a beatnik Communist.

For most of those hits, Mitch’s name was only in the credits.

Or maybe in small type, as “…with Mitch Miller and his Orchestra and Chorus.” Before “The Yellow Rose Of Texas”, Mitch had only scored one hit as a lead artist, and that way back in 1950: “Tzena Tzena Tzena.”

“Tzena Tzena Tzena” contains a number of, um, qualities (?) that would become a Mitch Miller signature. It came from an unlikely source – the British Mandate of Palestine, soon to become Israel – although perhaps a little less unlikely since it had recently been an even bigger hit for The Weavers – and it was relentlessly perky. It was a harbinger of things to come (and it was a 2.)

The taking-hit-songs-from-anywhere strategy was replicated when Mitch got The Four Lads to record “Skokiaan,” originally recorded by The African Dance Band of the Cold Storage Commission of Southern Rhodesia.

But even that wasn’t as confounding a song selection as “The Yellow Rose Of Texas:“

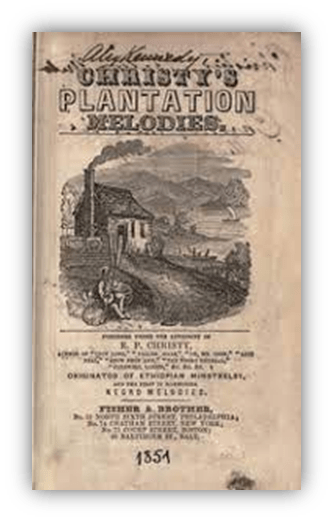

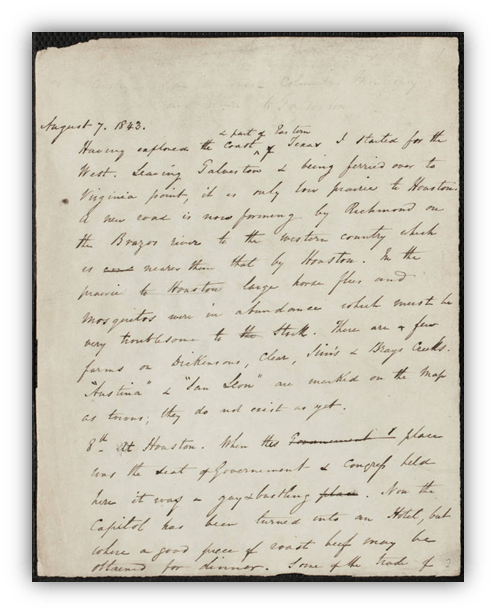

An old minstrel song first published in Christy’s Plantation Melodies. No. 2 in 1853.

Christy’s Plantation Melodies. No. 2 was the official song book of Christy’s Minstrels, one of the most popular minstrel shows at a time when minstrel shows were the most popular form of popular entertainment. “The Yellow Rose Of Texas” may have been an actual plantation melody, but it was more likely written by one of the blackface performers, written to make it sound like a plantation melody.

Mitch seems to have decided to make “The Yellow Rose Of Texas” sound as much as possible as though it were recorded in 1853.

This was, after all, just after “The Ballad Of Davey Crockett” had become a huge hit. Mitch was presumedly aiming for the same effect; the kids loved Davey Crockett, surely they’d love “The Yellow Rose Of Texas”, too.

Mitch knew all about what the kids liked: amongst all his other projects, he was the producer of Little Golden Records. Here’s his version of “Humpty Dumpty”/“Jack And Jill”/ “Skip To Ma Lou…” etc…

Let’s not forget the three records he made for the Cub Scouts:

If Mitch was aiming to make the next “The Ballad Of Davey Crockett”, he accomplished his goal.

And like “The Ballad Of Davey Crockett”, “The Yellow Rose Of Texas” was based on a semi-mythical historical figure.

Maybe.

Specifically, a character in the Texan Revolution. Even more specifically, in the Battle Of San Jacinto in 1836.

It turns out that there really was a “yellow rose.” And by “yellow rose” I mean “yellow girl.” And by “yellow girl” I mean “high yellow girl”, in the parlance of the time.

That is, a fairly light-skinned mixed race girl. In this case, a fairly light-skinned mixed race girl by the name of Emily West, born in Connecticut.

Emily found herself in Texas in 1835, not as a slave exactly – what with being born in Connecticut – but as an “indentured servant.”

But then she got kidnapped by the Mexican calvary, specifically the forces of Antonio de Padua María Severino López de Santa Anna y Pérez de Lebrón – his friends and enemies called him Santa Anna for short – who seemed to have a thing for Emily, what with her being the sweetest rosebud Texas ever knew, so much so that he was having sex with her in his tent when the Texan army attacked. What with their leader being distracted and otherwise engaged, the Texan forces overran the Mexicans in record time. Go Emily!

None of this was on Mitch’s mind when he produced his version of “The Yellow Rose Of Texas.” Nobody even knew about this whole backstory: not until the next year, when an old journal by an Englishman by the name of William Bollaert was published.

William had been told the story by Sam Houston who was leading the Texan charge. I guess it’s nice that Sam would give credit to his victory to Emily.

That story also would not have been in Mitch’s mind because not a single lyric in any known version of this song refers to the legend, or the battle at all.

Instead, Mitch had a new version by Don George on his mind, about whom nobody seems to know anything except that he was friends with Duke Ellington.

And Don George had “Yellow Rose” on his mind because it was suggested to him by a DJ named Bill Randle:

A hugely popular DJ in Detroit:

Who presented the The Interracial Goodwill Hour in the late 40s, before moving to Cleveland to become even more popular in the 1950s, when he also convinced The Crew Cuts to cover “Shh-Boom.” And Bill had “Yellow Rose Of Texas” on his mind because… who the hell knows?

So Don rewrote the lyrics into something a little less-minstrelsy; no longer, for example, does it start off with “she’s the sweetest girl of colour/ That this darkey ever knew;”

Other than that, Mitch made few changes, the record sounds more like something from the 19th century than even “The Ballad Of Davey Crocket.” There are marching drum rattles, there are pipes a-tottlin’, there are Confederate soldiers. None of this should have worked… and it didn’t.

That “The Yellow Rose Of Texas” would become a huge hit seems to have taken everyone by surprise; everyone except for Mitch himself who never for a moment underestimated how tasteless and tacky the record buying public could be.

When Columbia objected to pressing 100,000 copies, Mitch offered to buy back any copies they didn’t sell. He didn’t have to buy back a single one. They sold them all. And another million besides.

The success of “The Yellow Rose Of Texas” made no sense.

In any rational world it never would have happened. Records like “The Yellow Rose Of Texas” ought to have been the kind of thing that “Rock Around The Clock” killed off.

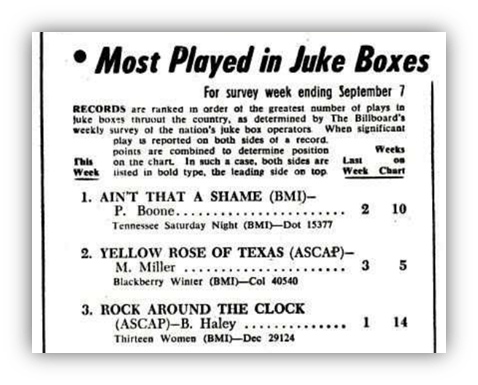

But no, “The Yellow Rose Of Texas” was the song that replaced “Rock Around The Clock” at the top of three of the four major Billboard charts – Best Sellers In Store, Most Played By Jockeys and Honor Roll Of Hits.

Only on the Most Played On Jukebox chart were the two songs separated by a couple of weeks of Pat Boone’s version of “Ain’t That A Shame” sitting at the top.

What kind of teenager in what kind of diner plays this in on a jukebox?

And to think when he started out, Mitch was a classical oboe player.

Of sufficient renown to play with the CBS Symphony Orchestra, George Gershwin, and even possessed enough hipster jazz-cred to play with Charlie Parker:

(on the Charlie Parker With Strings album of course, where he even appeared on the cover, down in the lower right hand corner)…

All musicians with too much pride and shame to ever consider making a record like “The Yellow Rose Of Texas.”

To be fair, it’s tough thinking of any other musician who would ever consider making a record like “The Yellow Rose Of Texas.”

Mitch Miller was a one-off. And “The Yellow Rose Of Texas” is a 1.

That’s a Lone Star.

Meanwhile, in Rock’n’Roll Land…

It’s “Tutti Frutti” by Little Richard

“WOP BOP A LOO BOP A LOP BOM BOM

Tutti Frutti, good booty

If it don’t fit, don’t force it

You can grease it, make it easy”

And then later on…

“WOP BOP A LOO BOP A LOP BOM BOM

Tutti Frutti, good booty

If it’s tight, it’s all right

And if it’s greasy, it makes it easy”

Those were the original lyrics of Little Richard’s first classic “Tutti Frutti.”

Sadly they didn’t make it onto the record. The world was not yet ready for a song so obviously about the importance of lubrication when engaging in anal sex.

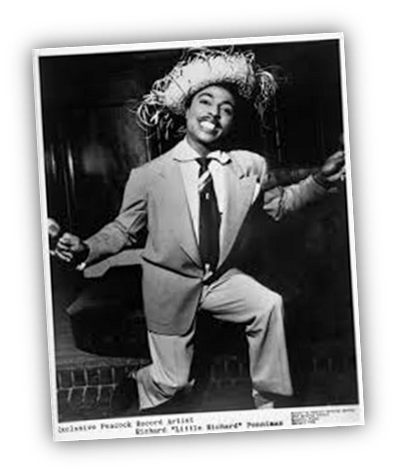

It’s quite incredible that the world was ready for Little Richard in any form.

Even in the form where the lyrics of “Tutti Frutti” were re-written into something trite enough to get played on the same 50s pop radio stations as “The Yellow Rose Of Texas.” Little Richard was the gayest thing ever to have happened to pop. “Tutti Frutti” is, after all, Italian for “all fruits.” And indeed, Little Richard was “all fruits.” “I’m the King Of The Blues” he used to announce in concert, even before he was famous. “And the Queen.”

“WOP BOP A LOO BOP A LOP BOM BOM”

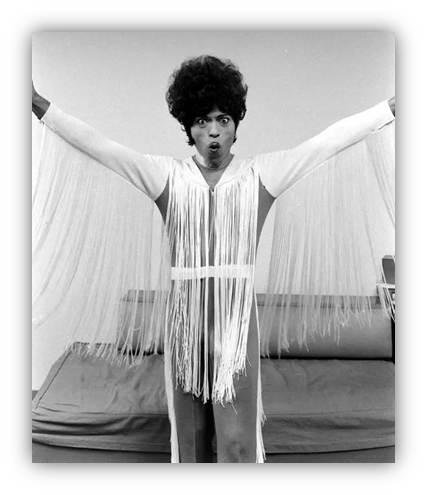

Before Little Richard was the most exciting thing in rock’n’roll, he was a drag queen.

Little Richard was still pretty much a drag queen when he became the most exciting thing in rock’n’roll.

Little Richard had started his career as a female impersonator one night when an actual female didn’t show up.

I can’t imagine he required much convincing.

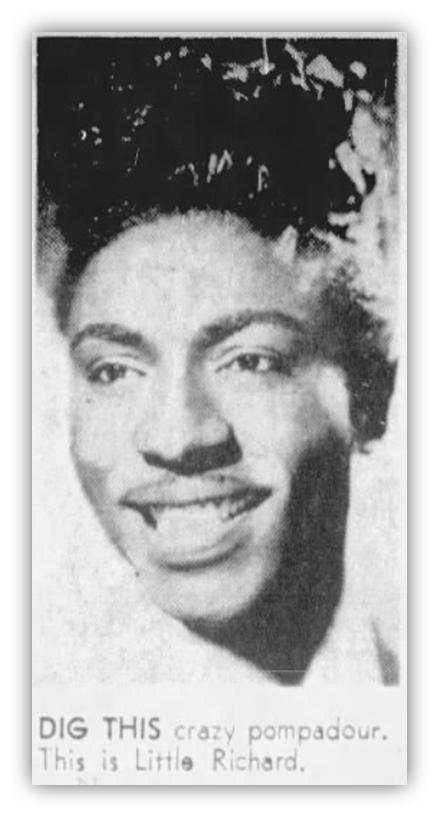

Soon Little Richard was hanging out with Billy Wright – or to use his drag name, Princess LaVonne -an openly gay blues singer, who taught Richard everything he knew about pompadour hair, tiny little moustaches and make-up.

(Pancake #31, if you yourself want to recreate the Little Richard-look)

Little Richard paid attention to it all. Particularly the pompadour.

Now it was 1955. And Little Richard was signed to Speciality Records, who were looking for someone to compete with Ray Charles.

But Little Richard said that he preferred Fats Domino. So off to New Orleans they went, to work with some of the same musos who played on the Fats Domino records. But, as the story goes, it wasn’t going too well. This may have been because they were recording slow blues ballads.

Nobody wanted a Little Richard singing slow blues ballads. Even before people knew what they wanted from Little Richard records people knew that they didn’t want that!

(Little Richard released a surprisingly large amount of music before finally figuring out what God had built him to do – that he had been built for spppeeeeeeed – having being signed to Victor in 1951, and releasing stuff like “Taxi Blues”, a song that would be vastly improved by a whole lot of “WOP BOP A LOO BOP A LOP BOM BOM“s)

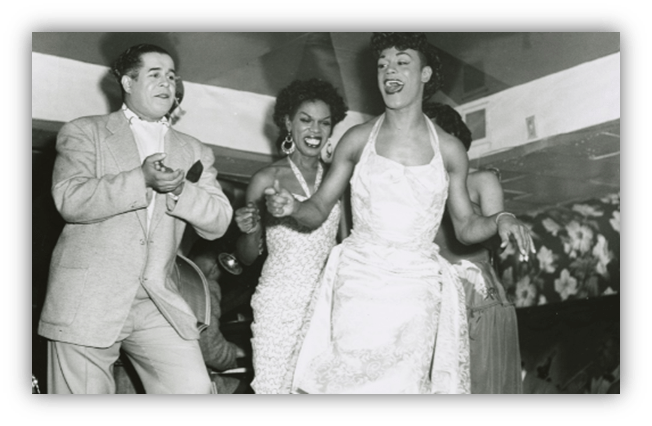

So they decided to take a break and headed off for the Dew Drop Inn.

The Dew Drop Inn wasn’t a gay bar exactly – instead it was one of the hottest Black joints in New Orleans, the joint all Black stars played when they played in New Orleans.

But one of its MCs was a drag queen, Patsy Valdeler, and they did hold the Halloween Gay Ball.

Little Richard may have previously performed there as a drag queen himself.

Little Richard felt comfortable there, and he sashayed up to the piano to…

“WOP BOP A LOO BOP A LOP BOM BOM

Tutti Frutti, good booty

If it don’t fit, don’t force it

You can grease it, make it easy”

Here, quite obviously, was a hit. Or at least a song that could be a hit, if not for the lyrics about lube.

So they called up a cook/waitress, and part-time poet by the name of Dorothy Labostrie.

He asked her to come up with something that wouldn’t get them banned; or worse.

This is where the story gets cute. Because Little Richard, faced with the challenge of having to sing those lyrics to a lady –a lady who had probably never even been to the Halloween gay ball – got all shy. In the end he either

- (a) turned to face the wall to recite the lyrics, so that he wouldn’t have to look her in the eye

- (b) or awkwardly whispered them to her.

Then she came up with new lyrics in about 15 minutes. And like all the best songs, it sounds like it.

That’s the legend, anyway.

Dorothy has her own legend that she likes to tell, that she wrote the whole thing herself, name and all, and named it after the ice-cream.

Fortunately however, they never touched the ““WOP BOP A LOO BOP A LOP BOM BOM” part, the most important – arguably the only important – part. Although there is at least one source that claims that it originally went “WOP BOP A LOO BOP A LOP GOD DAMN!”, so maybe there was a slight adjustment.

Even more adjustments were coming. Because, naturally Pat Boone had to cover it.

Unlike his cover of Fats Domino’s “Ain’t That A Shame” which went to Number One, Pat Boone’s cover of “Tutti Frutti” was only slightly bigger than Little Richard’s. I’m glad it exists.

I’m glad Pat changed the lyrics to “she’s a real gone (?) cookie yes’siree” if only because that’s the whitest thing ever.

But also because it means that someone tricked the fool into recording a song whose original lyrics were, I say it again:

“Tutti Frutti, good booty

If it don’t fit, don’t force it

You can grease it, make it easy”

Why couldn’t Pat Boone have brought back those lyrics?

Future Little Richard hits would be more obvious about their salacious subject matter, more faithful to the Little Richard-vision.

Their titles and simple rhymes likely gave kids the impression that Little Richard records were basically nursery rhymes, even though “Long Tall Sally” is very clearly about Uncle John having an affair with a bald woman (“Long Tall Sally” has a surprisingly cute origin story that we’ll get into early next year.)

“Tutti Frutti” is a 9.

Not the Pat Boone cover. Obviously, that one’s a 1.

“WOP BOP A LOO BOP A LOP BOM BOM!”

Meanwhile, in Novelty Doo-Wop Land…

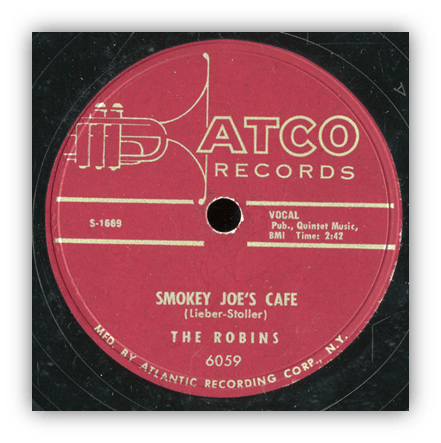

It’s “Smokey Joe’s Café” by The Robins

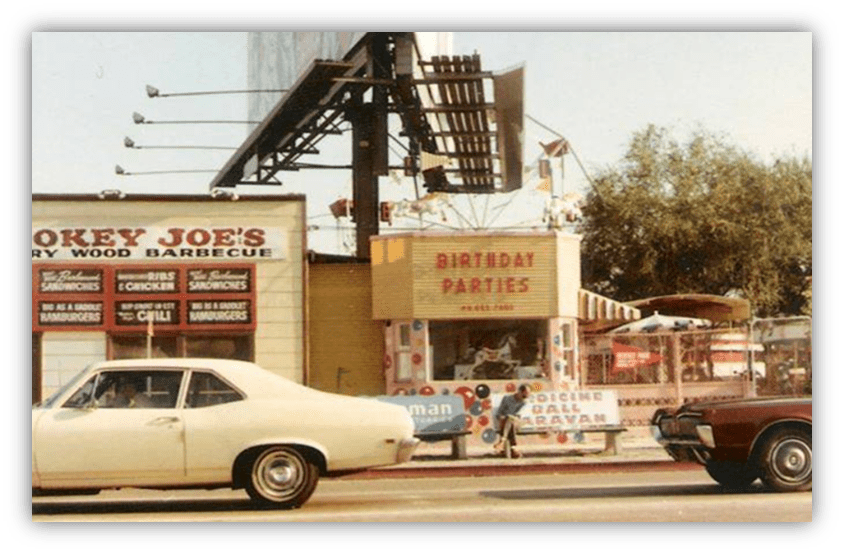

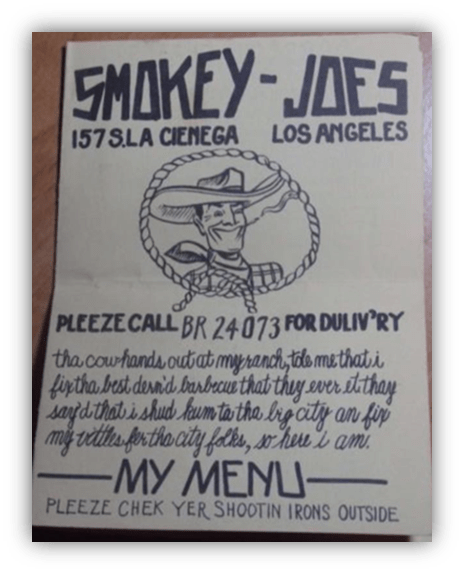

There was an actual Smokey Joe’s Café, in suburban Los Angeles. Sandwiched between an amusement park and a bunch of oil wells.

I am truly amazed at how many oil wells there were, just scattered around suburban Los Angeles. Now in Texas, I would believe it, but Los Angeles? That’s not the impression that I get from Beach Boys songs.

But I digress. This song is about Smokey Joe’s Café, and the bad service that Carl Gardner, The Robins’ lead doowopper – usually, but not always,– experienced there. Nowadays, you’d leave an angry one-star Yelp review. Back in 1955 you had to write a novelty doo-wop hit.

Calling Smokey Joe’s a “café” per se might be pushing it, which may be why they didn’t do that.

Smokey Joe’s was marketed as a cowboy themed BBQ restaurant that requested that you check your shootin’ irons outside.

That makes sense.

As the lyrics of “Smokey Joe’s Café” make clear, Smokey Joe’s weapon of choice is his great big kitchen knife.

Smokey Joe’s was the kind of cheap place where you might go to eat a plate of chilli beans.

- Did Carl choose a pot of “barbecued beans” for 30c?

- Or did he opt for the Rip-Snortin-Est Western Style Chilli And Beans for 40c?

Although: everyone’s favourite item on the menu appears to be the Barbecued Steerbeef Sandwich for 90c!! These prices are doing my head in!

Sadly, I cannot give you any information about the beans at Jack’s or John’s or Jim’s or Jean’s, although Carl makes it clear that these are all very viable options if you ever find yourself in a situation where you can no longer go to Smokey Joe’s, due to events such as those mentioned in the song.

These events are as follows:

- Carl has popped into Smokey Joe’s to mind his own business, and to eat his own beans

- When he is distracted by the sight – and smell! – of the woman sitting down next to him.

- The woman smiles at Carl.

- Carl’s heart goes boom.

Sadly this girl is dating Smokey Joe, the proprietor, chef and namesake of Smokey Joes Café. Smokey Joe, “crazy fool” that he is, storms out of the kitchen with a knife in this hand, throwing Carl out by the collar. This is truly terrible service. And maybe it’s just my imagination, but I can’t imagine that Smokey Joe is all that sanitary either.

Highly relatable “Smokey Joe’s Café” offered the perfect scenario for the goofiest group in doowop.

The Robins hadn’t always been such a goofy band.

The Robins had been one of the earliest doo-wop bands.

At about the same time as The Orioles released the first doo-wop classic – “It’s Too Soon To Know” in 1949 – The Robins were right there in the mix. Although at that point they called themselves The Bluebirds. Seriously, what was it with doowop bands and birds?

The Robins came out of the same Los Angeles doowop scene as The Penguins – birds again! – and The Platters, but their records sounded as though they came from a very different Los Angeles tradition: Robins’ records basically sounded like cartoons.

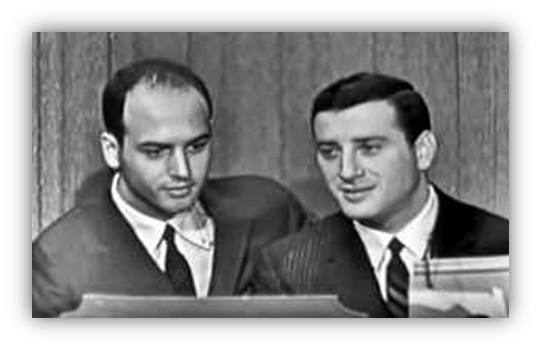

And the reason The Robins’ records sounded like cartoons was because the group were the muse of two Jewish kids, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller.

And when I say kids, I mean just that. Jerry and Mike were teenagers.

When they started writing songs and making records – and the first record they wrote was for The Robins – they were only 17. It was “That’s What The Good Book Says,” and it wasn’t a hit.

Jerry and Mike wrote songs based on, to use Jerry’s own words “a white kid’s take on a Black kid’s take on white society.” Carl felt astonished that these two Jewish teenagers got so much right about Black culture. How, he wondered, did they know?

Both Jerry and Mike had been born on the East Coast – Baltimore and Long Island respectively – both moving with their families to high schools on the outskirts of Hollywood as teenagers.

Both of their high schools have “notable people” lists on Wikipedia that just go on and on and on.

They met, discovered that they both loved R&B, and started writing songs.

And from the very beginning these were the most cartoonish R&B songs you can possibly imagine.

By 1955 – still little more than teenagers – Jerry and Mike had started their own label, to stop being screwed on the royalties they felt they should have earned from “Hound Dog” and “Kansas City.” The first band they signed? The Robins!

Jerry and Mike were not the only reason that The Robins sounded like cartoons.

There was also Carl Gardner, just arrived in town from Texas.

Carl had started performing with The Robins because the previous lead singer – Grady Chapman – kept on getting in trouble with the police.

He’d even ended up in jail. Only for a couple of weeks, but long enough that they had to hire Carl as a replacement. Nobody ever mentions exactly why Grady found himself in jail, but it is known that some of the members of The Robins were pimps, so it was probably in connection with that.

Appropriately then, their earlier hit had been “Riot In Cell Block #9.” They’d also made a record called “Ten Days In Jail” – about the amount of time that Grady had been in the lock-up – also written by Jerry and Mike.

Carl did not leave Texas for Los Angeles just to become the lead singer of a novelty doowop group. Carl had dreams of becoming a ballad singer.

Dreams of becoming Nat “King” Cole. But being a ballad singer was not what destiny had in mind for him. It’s honestly hard to imagine him being any good at it. But sounding as though he’d just stepped out of a cartoon… that he could do!

Carl sang with personality. He was a character. The goofiest of characters. He may have been pushing 30, but he sounds like a teenager. He sounds like the kind of kid who might find himself in the kind of predicament where he is barred from his favourite establishments. He sounds like the kind of kid for whom hijinks frequently ensue.

After “Smokey Joe’s Café” Jerry and Mike wanted to head back East, to New York, to take on the Brill Building crowd. And they had the opportunity to do so because, in the record industry, it’s not what you know, or how hot your records are, but who you know.

Or in this case, does Ahmet Ertegun, the co-founder of Atlantic Records, have a brother, who needs a tennis partner to go with him on his honeymoon, so that he can play tennis while his new wife goes shopping. Also, can Jerry play tennis?

And that’s how business deals are done in the music industry, and how Jerry and Mike’s got their records distributed by Atlantic and started to generate proper hits.

By this time it was obvious that Carl and ex-boxing champion/bass singer Bobby Nun were the stars of the show – Carl sounding goofy, Bobby’s bass sounding even goofier – and that the other doo-woppers were disposable.

So the rest of The Robins got dumped, and Carl and Bobby were renamed The Coasters, for once not named after a bird.

Instead they were possibly named after the fact that they were coasting from coast (west) to coast (east)).

The others stayed in L.A., kept the name, and became just another late 50s doo-wop group.

As The Coasters, Carl and Bobby’s first hit would be “Down In Mexico.” It was a similar scenario; the boss is even a cat named Joe. A chick arrives in the second verse; but instead of being threatened with a knife, she gives Carl a sexy little dance. Joe doesn’t seem to mind. His new career playing blues pianna in a honky-tonk down in Mexico appears to have chilled him out. “Down In Mexico” is a 10.

By this time novelty doo-wop was starting to become its own sub-genre.

Particularly in Los Angeles, with The Cadets taking the radio-play format that The Robins had started with “Riot In Cell Block #9” to the next level with “Stranded In The Jungle”, complete with jungle noises, cannibalism (sample lyric: “Great googa mooga, lemme outta here!”) and one verse in which he hitchhikes on a whale. It was surreal shit.

One of the members of The Cadets would ultimately end up in The Coasters, just in time for them to grab a Number One during the Great Novelty Song Boom of 1958!

the American people are having none of that: what they really want is wall-to-wall harpsichords and French horns

It’s 70 years later and I still want that.

On the country side of the tracks, Jean Shepard was riding high with “A Satisfied Mind”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z3sBY_nBPtU

Great stuff, DJPD. I’ve never heard “Smokey Joe’s Cafe” before and it’s a hoot. Also, the first time I heard “Stranded In The Jungle,” it was by the New York Dolls on Don Kirschner’s Rock Concert.

https://youtu.be/ON-RsfrhS4I?si=iKfc4sRy1_dfJ_j3

As y’all probably know, Mitch Miller kept Columbia virtually rock-free until he left the label in 1965. Clive Davis, his successor, turned that around quickly with hits by the Byrds and Simon & Garfunkel, among others. He made peace with the genre to a certain extent when he and his “gang” covered John Lennon’s “Give Peace a Chance” on the 1970 LP Peace Sing-Along.

Tutti Frutti is a 10 and I won’t be convinced otherwise.

Smokey Joe’s Cafe is a great find with the usual fascinating backstory behind The Robins.

I can get by without hearing Yellow Rose Of Texas again.

This is great. I have been listening to 50s music for a long time. But I did not know much of the back story. Very interesting stuff.

Smokey Joe’s Cafe was torn down to build the Beverly Center, which housed the first American location of the Hard Rock Cafe for several decades.

Down the street is Pan Pacific park, which used to be the Pan Pacific auditorium, which is what was used in “Xanadu”!

Presenting to Official It’s The Hits Of September-ish 1955 Spotify playlist! From “Tutti Frutti” to “Reet Pettite.”

Featuring The Coasters, Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, Jackie Wilson… and Little Richard of course, it’s a 1950s rock’n’roll party playlist!

https://open.spotify.com/playlist/4Q8usV867ErvuLuRxjFwt9?si=eb84b0301d1b48bd