The Hottest Hit On The Planet:

“Sh-Boom” by The Chords and The Crew Cuts

Two versions of a silly little love song were racing up the charts. A silly little love song, with silly little lyrics. Silly little lyrics like…

“Day dong da ding-dong

A-lang-da-lang-da-lang

Ah, woah, woah, bip

Ah bi-ba-do-da-dip, woah”

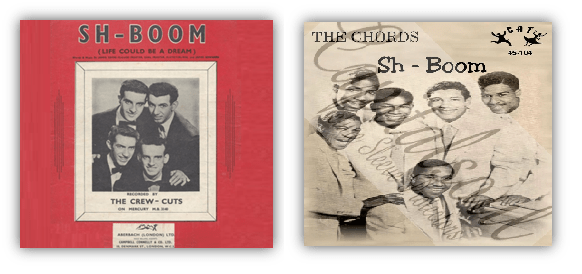

The song was called “Sh-Boom,” and it was both written and performed by the members of a doo-wop group from the Bronx known as The Chords. They wrote it while they were sitting in a car. “Boom”, it turns out, was a popular piece of Bronx slang. As best as I can make out, it was a way of verbalizing a period, which feels completely unnecessary.

“Sh-Boom” was racing up the charts. Then suddenly, as if out of nowhere – or more precisely, from Toronto, Canada – came barbershop quartet The Crew Cuts, and they too recorded “Sh-Boom,” and that little record overtook The Chords’ original… and became the Number One song in the country!

This upset a lot of people.

It continues to upset people decades later.

This sort of thing – an R&B hit “crossing over” to “Pop”, usually when an extremely naff white performer covered it – was happening an awful lot at the time.

The McGuire Sisters version of The Spaniels’ “Goodnight, Sweetheart, Goodnight” is a classic example, if not exactly a classic recording.

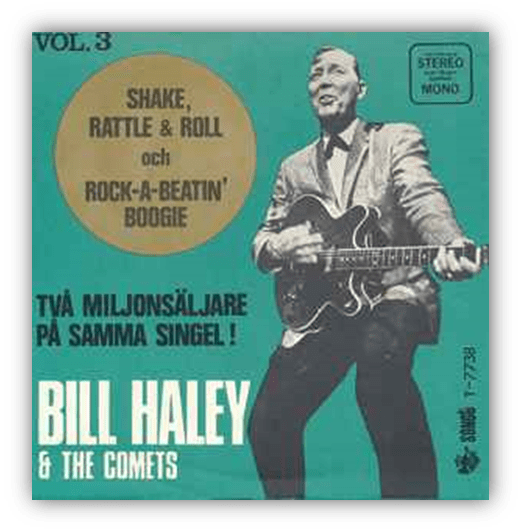

The somewhat less-naff Bill Haley version of Big Joe Turner’s “Shake, Rattle & Roll” is another. Each of these cover versions raced up the “Pop” charts only a few short weeks after the originals began their accent of the “R&B” charts. Plenty more examples would follow.

Having lived through such a trend, many people have understandably embraced the theory, that all these “Pop” versions of R&B songs were part of a deliberate campaign to keep the Black man down. Also that the etymology of the term “cover version” can be traced back to the racist act of “covering” a Black original with a white copy, concealing it like white-wash paint.

According to amateur rock’n’roll historian Don McLean (please read to the tune of “American Pie”):

“Back in the days of black radio stations

and white radio stations (i.e. segregation),

if a black act had a hot record the white kids would find out

and want to hear it on “their” radio station.This would prompt the record company to bring a white act in-

to the recording studio and cut an exact, but white, version of the song

to give to the white radio stations to play

and thus keep the black act where it belonged:On black radio.”

DON MCLEAN, AS QUOTED BY RAY PADGETT IN “Cover Me: The Stories Behind the Greatest Cover Songs of All Time

Don’s probably exaggerating a tad for effect. The man can do that. He’s an artist.

And whilst there is no doubt that the major record companies were producing “Pop” versions of R&B hits for the “Pop” market – Billboard often gushed about the practice – it’s debatable that it quite as calculated as Don suggests. It’s not impossible that Don is flexing his Boomer-saviour-complex, claiming that his generation rid the world of racism through the power of rock’n’roll.

There were certainly a few hit records that do sound “exact, but white.” Such as the infamous 1948/9 case of “A Little Bird Told Me”…

… a case that actually did turn into just that: a court case. The two versions were so alike that the makers of the original Black R&B record – sung by Paula Watson – took the makers of the white “Pop” cover – sung by Evelyn Knight – to court for copyright infringement. Sadly, Paula lost. Turns out you can’t – or couldn’t – copyright an “arrangement.”

But this does not really appear to be an issue for “Sh-Boom.” Nor for “Shake, Rattle & Roll” and “Goodnight, Sweetheart, Goodnight” for that matter (given that The Spaniels were practically-teenage boys, and The McGuire Sisters were grown adult women, nobody was ever going to confuse the two). The Crew Cuts version of “Sh-Boom” is certainly similar, but it’s not even close to being “exact.” It is very white, though.

As for the etymology of “cover version”, the phrase does seem to have first appeared at about this point.

A Chicago Tribune journalist is said to have reported in 1952 that the phrase was “trade jargon meaning to record a tune that looks like a potential hit on someone else’s label.”

By 1954 Billboard had shortened “cover version” to just “covers”, a phrase they used to describe… a Bing Crosby version of “Secret Love.”

The phrase “cover version” didn’t just appear in 1952 because the music industry was suddenly filled with cover records. The reason the phrase had not existed before then was because there was no need for it. Virtually every record in the stores at the time was a cover. It was the norm. Once a song looked as though it might be a hit, every pop star would rush to the studio to record their own version – or at least every record label would – sending all these multiple versions off to fight it out in the marketplace.

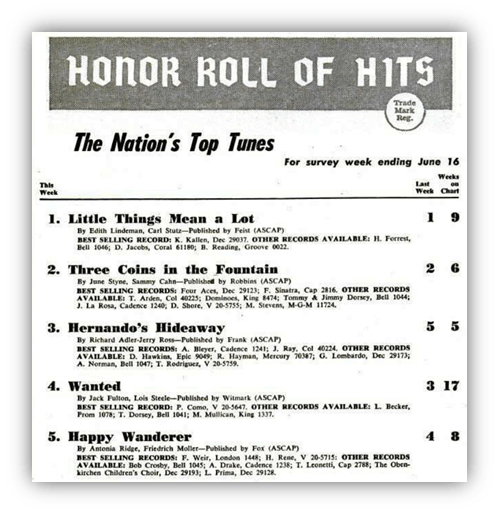

So prevalent was the practice of having multiple versions of the same song in the stores, and on the radio, that the most important Billboard chart in 1954 – based on the fact that it was printed in a font about five times as large as all the other charts – was the “Honor Roll Of Hits.” This chart included the song title, the names of the writers and publishers, and then a long list of the available recorded versions. It was a song-based chart, based on the sum of all the sales of all the different versions of a song.

A Louis Prima version of “The Happy Wanderer”?

The Dominoes covering “Three Coins In The Fountain?” Seriously?

Apparently so…

These songs typically came from Hollywood or Tin Pan Alley. They were written by professional songwriters who couldn’t sing, and not – as was often the case with doo-wop and sometimes the case with R&B – the performers themselves.

In such a world, why would anyone have intuitively thought that Rhythm & Blues songs might be off limits?

If they heard an R&B record and it sounded like a hit, why wouldn’t they rush to the studio to record a “Pop” version? Of course it would be a “Pop” version. They were “Pop” stars. And rushing into the studio to record a version of the latest hits is what pop stars had been doing since before there was a word to describe the practice.

Don’t get me wrong: the practice of “black radio stations and white radio stations” was, by definition, racist. But is it that much different to what we have today, with segregation simply being replaced by market segmentation? With separate radio formats, each with their own chart, for Pop and Country and Latin and Christian and Dance/Electronic and R&B/Hip-Hop and Rock/Alternative? And with race still being a factor in deciding who gets played on what?

The primary difference between then and now is that now we have a Hot 100.

A One Chart To Rule Them All.

In 1954 they did not have a Hot 100. They didn’t even have anything that might remotely be considered as a sort of substitute proto-Hot 100.

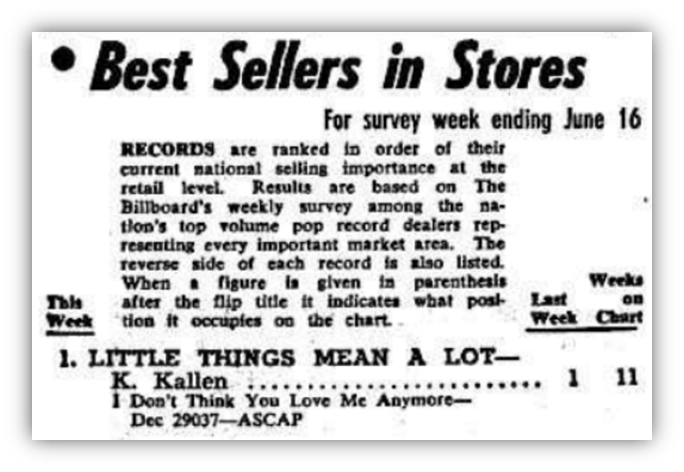

Most sources – Wikipedia, Joel Whitburn, Billboard itself – when forced to discuss chart positions during the pre-Hot 100 era will point you to the “Popular Records- Best Sellers In Stores” chart. That sounds like a logical direction in which to be pointed.

But the “Popular Records- Best Sellers In Stores” chart doesn’t tell the whole story. Not even close.

So: I’ve spent way longer than I should have, going down the rabbit hole of Billboard’s chart tabulation methodology during the pre-Hot 100 era, trying to understand how it all worked. I will now present to you, my findings.

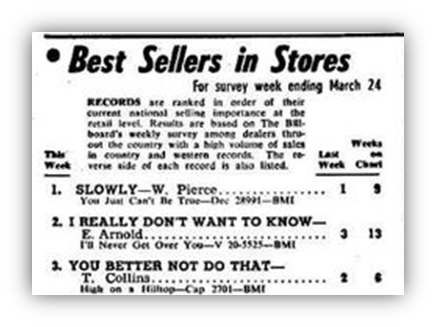

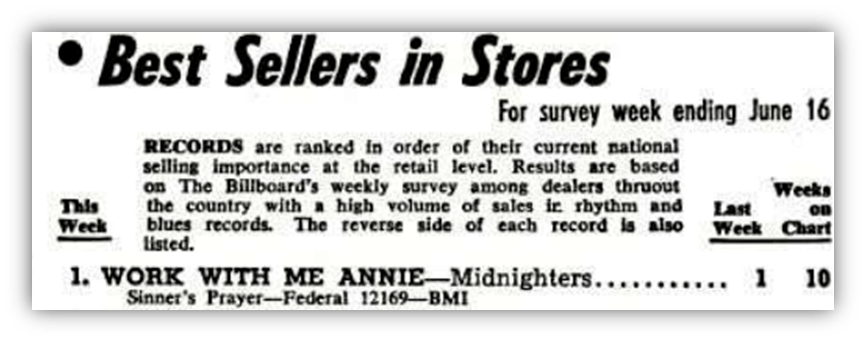

By 1954 there were three charts. Actually there were more – there were eight – but let’s keep things simple. Let’s try to compare like with like and focus on the “Best Sellers In Stores” charts. Of which there were three. A “Popular Records” chart. A “Country” chart. And a “R&B” chart. So, what were their methodology? What were they measuring?

Well for one thing, they were all separate. The “Country” and “R&B” chart were not simply components of the “Popular Records” chart. Records tallied in the “Country” and “R&B” chart were not also counted in the “Popular Records” chart. The “Popular Records” chart was off in a world of its own.

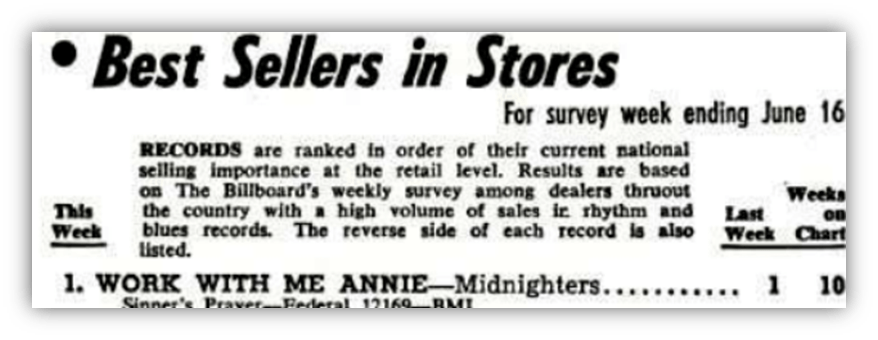

Here’s Billboard’s brief description of how they gathered the data for “R&B – Best Sellers In Stores” which is that they surveyed “dealers throughout the country with a high volume of sales in rhythm and blues.”

Bit vague – makes you wonder what the cut-off point was – but it seems simple enough.

This is much the same methodology as for “Popular Records”, in which Billboard surveyed “pop record dealers.” If you want to read that as being synonymous with “white record dealers” you probably can.

This is the chart that everyone uses as a Hot 100 substitute.

One that does not include sales through record stores “with a high volume of sales in rhythm and blues.” Or “with a high volume of sales in country” for that matter. One that is just the non-R&B, non-country, “Pop” market.

Using the 1954 “Popular Records – Best Sellers In Stores” as a Hot 100 substitute, would be like using Pop Airplay today (current Number One? “Too Sweet” by Hozier). Or, since few Baby Boomers were old enough to buy records yet, the Adult Contemporary Radio chart.

(Current Number One? You’ve got to be kidding me? Still, Miley’s “Flowers”? It’s been Number One – on and off – for over a year!!!).

Now, the “Popular Records” market was far larger than the “R&B” market, but it certainly wasn’t the whole game. “Popular Records – Best Sellers In Store” should never be considered as any sort of proto-Hot 100. By acting as though it is, it’s almost as though we are asking the question, if a Black artist sells a million copies of a record – and a whole lot of R&B records were selling a million copies – – but no white people hear it, does it make a sound? And deciding that the answer is “no.”

This also leads to a twisted reading of rock’n’roll history.

If looked at from a purely “Popular Records – Best Sellers In Stores” perspective, then “We’re Gonna Rock (Around The Clock)” looks like a Big-Bang moment.

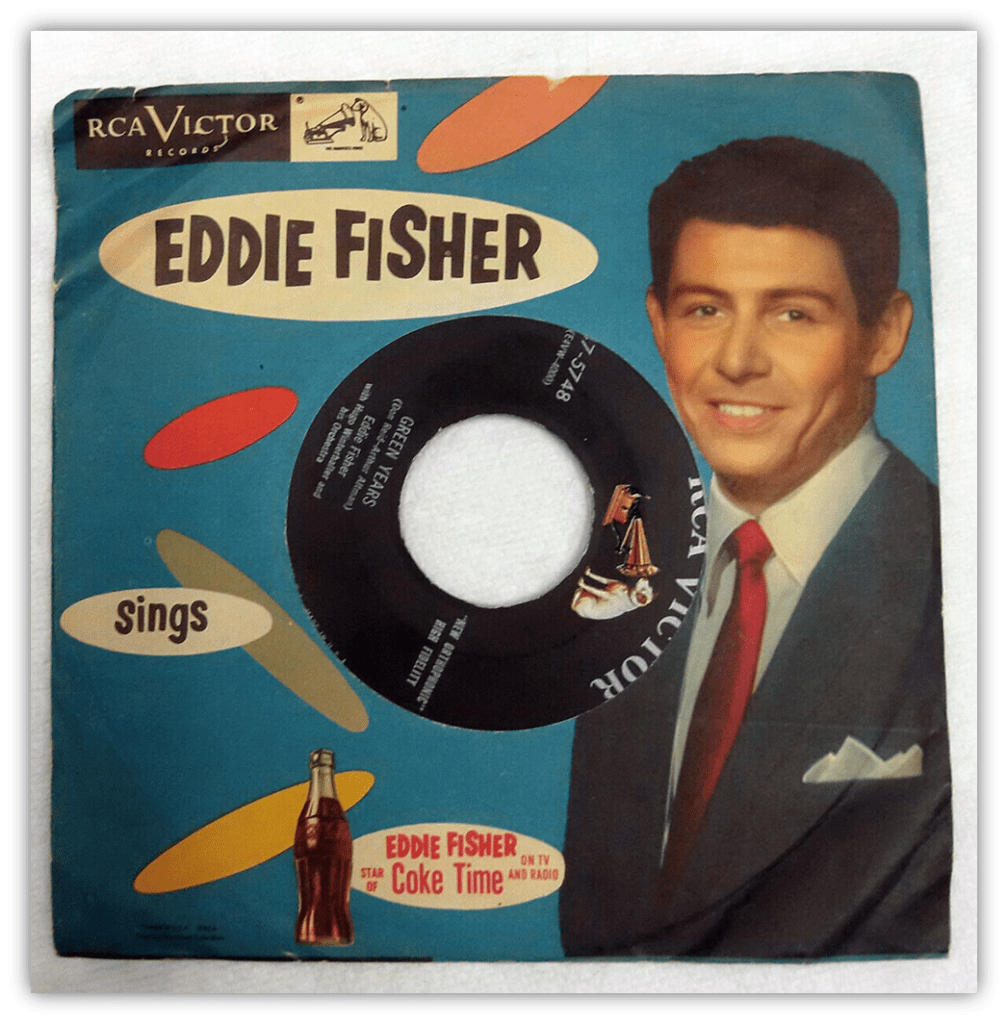

For years there’s nothing but Perry Como, and Doris Day, and Rosemary Clooney, and Jo Stafford, and… ugh… Eddie Fisher at Number One…

…and then suddenly… “OneTwoThreeO’ClockFourO’Clock Rock!!! Boom!”

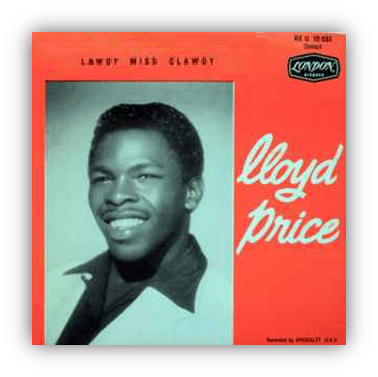

But “We’re Gonna Rock (Around The Clock)” looks far less like a Big Bang moment if you realize that, had they been included as part of a Hot 100-style all-inclusive chart, then such classics as Big Joe Turner’s “Shake, Rattle & Roll,” The Drifters’ “Money Honey”, Lloyd Price’s “Lawdy Miss Clawdy”, and several Fats Domino records – all of which sold more than a million copies – could very well have already reached Number One before it. At the very least they would have come tantalizingly close. I guess we’ll never know.

When looked at purely from a “Popular Records – Best Sellers In Stores” perspective – where a classic like “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” doesn’t make the chart at all – these songs seem like obscure underground records, pop-prophets completely ignored in their own time, when they were pretty much the hottest hits in the country!

So, what does all of this have to do with covers? What does this have to do with “Sh-Boom”?

A lot of the frustration with the “Sh-Boom” situation stems from the belief that, if an R&B song was ignored by “Pop” radio – if it didn’t then appear on the “Popular Records – Best Sellers In Stores” chart – then it was being consigned to the margins. But the R&B market was quite a big margin. If you can sell a million copies of a record just to R&B fans, do you really need “Pop” fans?

The “Pop” ecosystem and the “R&B” ecosystem were their own separate worlds, with only a handful of records occasionally crossing over from one to the other. If an R&B song sounded as though it had potential to be a “Pop” hit, then record companies would race to record a “Pop”-pier version, much as they had been doing for Tin Pan Alley and Hollywood songs for at least a decade.

It went the other way too: with doo-wop and R&B performers recording doo-wop and R&B versions of “Pop” hits. The Orioles recorded “Secret Love.” The Dominoes, as mentioned above, recorded “Three Coins In The Fountain.” The doowop/R&B cover strategy doesn’t appear to have been nearly as lucrative on the R&B charts as the “Pop” cover strategy was on the “Pop” charts, but it certainly existed. Case in point, the debut single by the heroes of our story, The Chords.

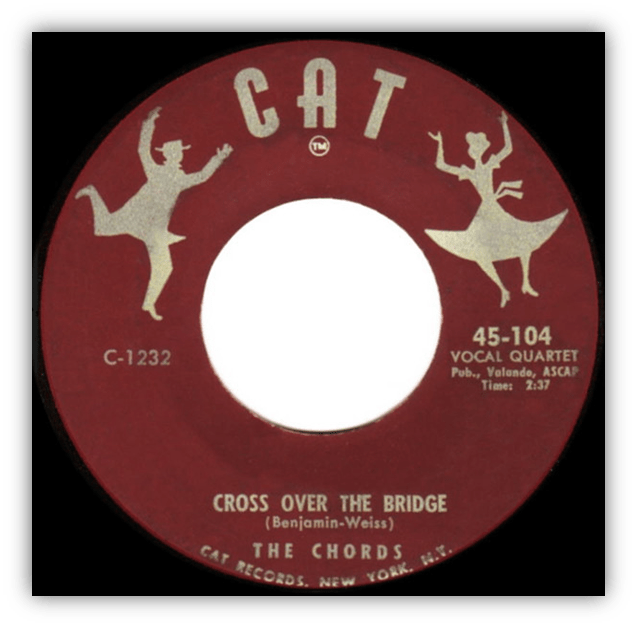

The Chords had recorded a doo-wop version of a Patti Page hit – “Cross Over The Bridge” – co-written by Bennie Benjamin, a Black man who wrote the music for a ridiculous number of 40s pop classics: “I Don’t Want To Set The World On Fire”, “When the Lights Go On Again (All Over the World)”, “Wheel Of Fortune”, “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood”…

The Chords weren’t especially keen about the idea. They wanted to release “Sh-Boom.” They thought “Sh-Boom” was a hit. Their record label – Cat, an offshoot of Atlantic – disagreed. They didn’t think “Sh-Boom” sounded like a hit at all. I know, I can’t believe it either. They finally allowed The Chords to use “Sh-Boom” as the B-side.

The Chords’ version of “Cross Over The Bridge” was a complete flop. Then a DJ in California decided to play “Sh-Boom” instead – and suddenly, it was everywhere!

Whilst most R&B hits stayed R&B hits and didn’t find much – or any – success on the “Pop” charts, “Sh-Boom” was different. The Chord’s record was almost as popular on the “Pop” chart as it was on the “R&B” chart! It was a hit on multiple radio formats!! There was simply something magically universal about it. It spoke a universal language. A language with words such as:

“Day dong da ding-dong

A-lang-da-lang-da-lang

Ah, woah, woah, bip

Ah bi-ba-do-da-dip, woah”

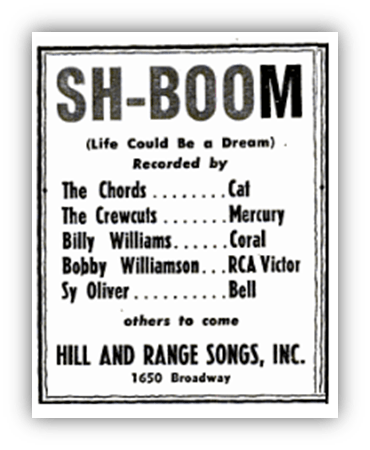

“Sh-Boom” was so irresistible that within a few weeks there were already five versions battling it out on the market, with multiple more versions still to come.

According to one source, this was Atlantic Records idea. “Sh-Boom” was blowing up so fast they simply couldn’t keep up with demand. The easiest way for them to satisfy demand was to outsource to other record companies and other artists. Since Atlantic owned the publishing rights, they got a slice of the royalties anyway.

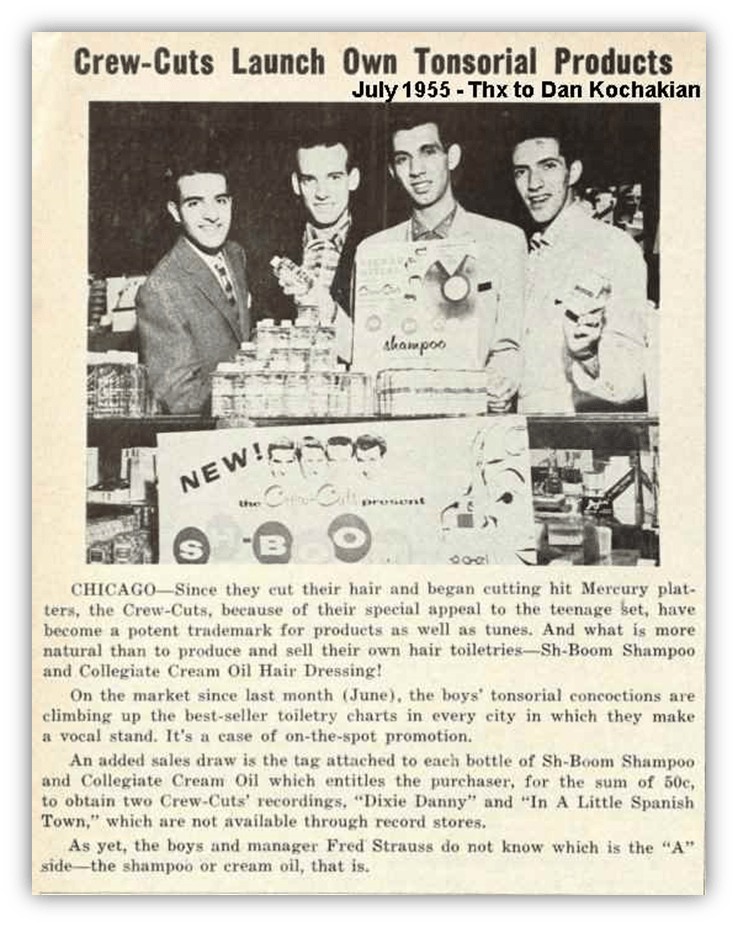

I’m unclear of how much of this money got back to The Chords themselves, although rumour has it, they capitalized on their success by starting a company that marketed a Sh-Boom shampoo.

Let’s have a listen to these versions.

The Billy Williams version was a bouncy R&B bop and a lot of fun. Even more fun than The Chords version if that’s possible. But it wasn’t a hit.

Bobby Williamson – oh this isn’t confusing at all – was a country singer and his version ain’t great. A few weeks later another country version would appear, Leon McAuliffe & His Western Swing Band, sounding not a little like Bing Crosby. It might be the only version of “Sh-Boom” ever recorded that didn’t aim to sound as ridiculous as it possibly could.

Two country versions of “Sh-Boom” in quick succession might seem odd.

But then again, Hill and Range were predominantly a country-music song publisher.

At least they were until they met Elvis… but that’s another story. They also weren’t exactly shy about diddling songwriters, another reason to feel concerned that The Chords may not have gotten quite as large a slice of the “Sh-Boom” pie as they should’ve.

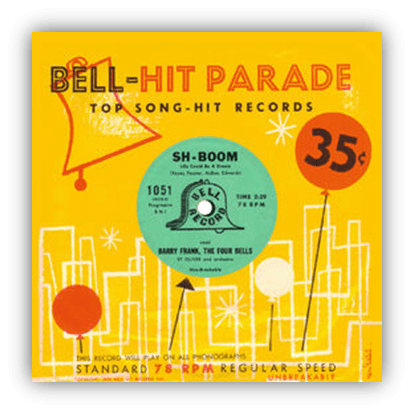

Sy Oliver was a Black jazz trumpeter, which sounds promising. Maybe it’s a be-bop version! It’s not.

Sy is just leading an orchestra playing behind yet another doo-wop group: Barry Frank and The Four Bells. Ho-hum.

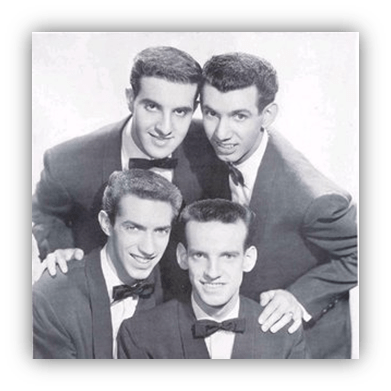

The most successful version of “Sh-Boom” by far was by Canadian barbershop quartet, The Crew Cuts, sporting the 50s rendition of that titular hairstyle. Since pretty much all male hair was short and tidy at the time, it’s difficult to tell the difference between The Crew Cuts hair and that of anyone who wasn’t Elvis. But I do believe it’s slightly shorter.

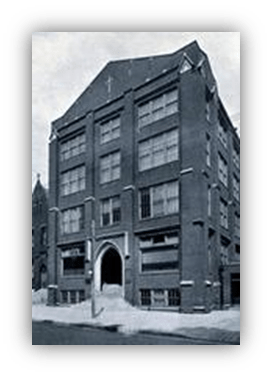

Canada in the early-to-mid 50s was a hot spot for barbershop quartet talent.

This was largely due to the teachers at St. Michael’s Choir School in Toronto, a school that not only produced The Crew Cuts, but also The Four Lads!

St Michael’s Choir School was initially called Cathedral Schola Cantorum, but now it’s St Michael’s Choir School, not Cathedral Schola Cantorum. Been a long time gone Cathedral Schola Cantorum…

The Crew Cuts had scored a handful of hits by this stage, including the deliriously perky “Crazy ‘Bout Ya Baby,” which they admitted to writing themselves (it’s a 3) and which made the “Pop” Ten.

You couldn’t really call them famous exactly, but more people knew who they were than knew Barry Frank and The Four Bells.

Also in their favour was the immense and unfathomable popularity of barbershop quartets in 1954. Elsewhere in the “Pop” Ten were The Four Aces with “Three Coins In The Fountain” – yep, it was still hanging in there – and The Gaylord’s with “Little Shoe Maker” (it’s a 4). Although The Gaylords were technically a trio, and not a quartet, they feel as though they belong in this list.

The Crew Cuts also benefited from the fact that, if you have lyrics such as “day dong da ding-dong, a-lang-da-lang-da-lang, ah, woah, woah, bip, ah bi-ba-do-da-dip, woah” then you want them to sound as ridiculous as possible. It shouldn’t be hard. After all, the lyrics are “day dong da ding-dong, a-lang-da-lang-da-lang, ah, woah, woah, bip, ah bi-ba-do-da-dip, woah.” The Crew Cuts did not disappoint. The Crew Cuts sounded ridiculous.

Also, the gong.

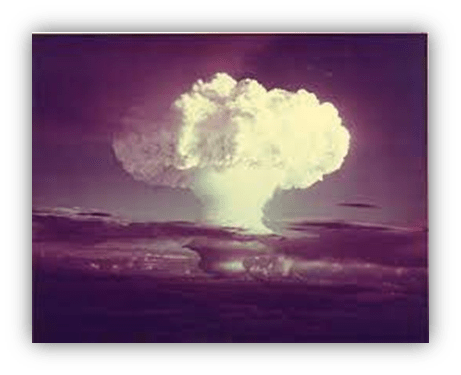

The Crew Cuts version of “Sh-Boom” was the only version of “Sh-Boom” with a gong. I don’t think we can underestimate the appeal of that gong. Some have suggested that the gong was supposed to represent the explosion of an atomic bomb, specifically the one that the United States had just detonated at Bikini Atoll.

A cute little reminder that there was a (Cold) War going on.

I like that theory, even though it’s about as ridiculous as “day dong da ding-dong, a-lang-da-lang-da-lang, ah, woah, woah, bip, ah bi-ba-do-da-dip, woah.”

What The Crew Cuts didn’t have going for them however, was looks. All the special effects – by 1954 standards at least – cannot obscure the spooky spectacle of those ears, or the freaky forehead of Frankenstein’s monster singing “day dong da ding-dong” towards the end.

Whilst most of the white “Pop” versions of the R&B and doo-wop tunes of the mid-50s have been forgotten, with widespread agreement that it was a terrible idea that should never have been attempted, the appeal of the “Sh-Boom” gong has helped The Crew Cuts hang in there in the cultural imagination.

Sure, The Chords original has four times as many Spotify streams, and rightly so, but The Crew Cuts haven’t totally embarrassed themselves.

The Chords’ version of “Sh-Boom” is an 8. The Crew Cuts’ is a 7.

Meanwhile, in R&B Land:

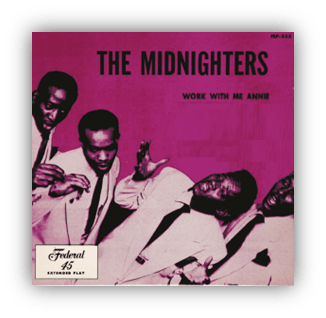

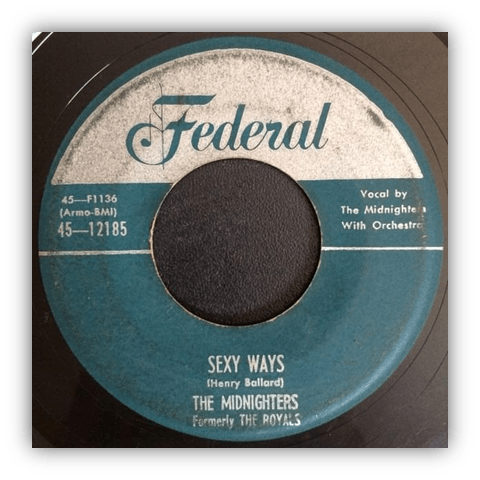

“Work With Me, Annie” by Hank Ballard & The Midnighters

“Work With Me, Annie” was written by Hank Ballard in an attempt to equal – or hopefully exceed – the naughtiness of his favourite song: “60 Minute Man” by The Dominoes.

That was quite a challenge he’d set for himself, and I’m not convinced that he altogether succeeded. After all, “60 Minute Man” was a song in which a character by the name of Lovin’ Dan smoothly lays out his schedule of seductive satisfaction: 15 minutes of kissing, 15 minutes of teasing, 15 minutes of pleasing and 15 minutes of blowin’ his top! Phew, I’m exhausted just thinking about it. (“60 Minute Man” is a 10)

“Work With Me, Annie” didn’t quite match the titillating dirtiness of “60 Minute Man,” but it certainly matched its success. It sold a million copies. Thus we can add “Work With Me, Annie” to that list of R&B hits that probably would have gone to Number One in an all-inclusive Hot 100-style chart.

I guess we’ll never know.

One factor that may have impeded the success of “Work With Me, Annie” on such a hypothetical chart is that it didn’t receive much airplay. It couldn’t. It was banned by the FCC.

A lot of R&B records were being banned at the time.

The New Pittsburgh Courier – an African-American newspaper – had been campaigning against “smutty” records since a year earlier. But in November 1954, they took their campaign to the next level, with a front-page headline proclaiming: “Sin, Sex and Seduction Records Fouling Airwaves,” damning “the medium of smutty records” and irresponsible DJs “making the air blue with records that fall little short of sheer filth!”

It also featured a picture of this charming fellow.

“The blues is good music.” it concluded. “So is food, but it can poison you. Smutty records poison minds, and you can’t use a stomach pump on the mind.”

You can’t argue with that logic.

In Houston, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People campaigned against indecent records on the radio, leading to the Juvenile Delinquency and Crime Commission establishing a sub-committee by the name of “Wash Out The Air.”

Which proceeded to ban 26 songs thought to be “suggestive, obscene, and characterised by lewd intentions.”

To be fair, many of those songs were “suggestive, obscene, and characterised by lewd intentions.” That’s one of the things that’s great about them.

It wasn’t just “Work With Me, Annie” and “Sixty-Minute Man” that got banned. Ray Charles’ “I Got A Woman” was on the list!

I know, right? You would have thought that Ray’s song – which promotes a decidedly conservative world view, what with his woman knowing that “a woman’s place, is right there now in her home” – would have been safe!! (“I Got A Woman” is a 9)

“CONTROL THE DIM-WITS!!” Billboard demanded, worried that “a number of disk manufacturers – by overstepping propriety and good taste – have already precipitated legislative action.” Legislative action such as Memphis police confiscating jukeboxes and fining the operators $50.

The police were particularly eager to stamp out any jukeboxes that contained the particularly delightful “Honey Love” by The Drifters. There was something suggestive about the way Clyde McPhatter kept on singing “it”(it’s a 9)

Billboard was particularly concerned since, as they noted, the R&B market was booming! “To allow a narrow band of dim-witted men to impede the progress of the burgeoning field would be an inexcusable folly.”

Hank Ballard was clearly one of those dim-witted men.

Lyrically – or as the pun went at the time “leer-ically” – “Work With Me, Annie” doesn’t sound that lurid. For one thing there aren’t many lyrics to be offended by. “Give me all my meat”? I guess that’s the most objectional. Or is it “our hot lips kissing”?

But what “Work With Me, Annie” lacks in lyrical content, it more than makes up for in other vocal noises:

A whole lot of horny “ooooh-weeee”s for example – which could, I suppose, be imagined to represent pleasurable pelvic thrusting. And probably were. There’s no doubt that “Work With Me, Annie” is “suggestive, obscene, and characterised by lewd intentions.”

Hank and The Moonlights followed up “Work With Me, Annie” with “Sexy Ways.” Which also sold a million copies.

“Sexy Ways” is “Work With Me, Annie” squared: the guitar intro is pretty much the same, but this time it’s distorted, dirtier. And as for the lyrics?

“I said a shake baby shake baby shake till the meat rolls off your bones

Shake baby shake baby shake till your mama and your papa come home

Shake baby shake I just love your sexy ways”

Hank was clearly obsessed with meat.

Also:

“Wiggle, wiggle, wiggle, wiggle, wiggle, til your hips get tired and weak”

“Sexy Ways” is probably just vague enough for Hank to being able to plausibly claim that it’s about dancing. Not that anyone would have believed him. And clearly they didn’t, since it got banned as well. (it’s a 9)

Hank followed that one up with “Annie’s Aunt Fannie,” by which time they were clearly just taking the piss. Not to mention “Annie Had A Baby,” the inevitable conclusion to all of this working. And what a sad conclusion it is. Annie’s baby means that she can’t work no more. Poor Hank!

As you may have noticed, these songs pretty much all sounded the same. And when other artists started releasing their own answer records, grabbin’ them some of that Annie money, they all sounded much the same as well.

The biggest of these was the weirdly named “The Wallflower,” the first hit by the fabulous Etta James. Weirdly named because it should clearly have been titled “Roll With Me, Henry.” I don’t think anyone has ever called it anything else.

“The Wallflower” was too a huge hit and would likely have been even bigger if not for… but that’s a story for another time.

“Work With Me, Annie” is an 8.

Meanwhile, in Doo-Wop Land:

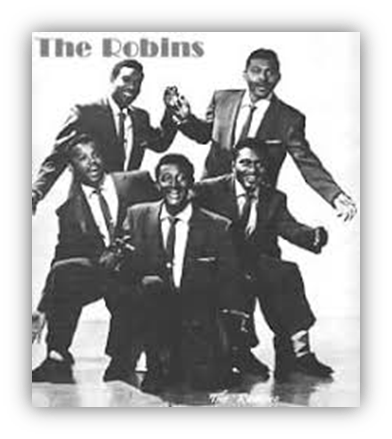

“Riot In Cell Block #9” by The Robins

Mike Stoller and Jerry Leiber were two Jewish kids who met in L.A. in 1950. Mike was attending Los Angeles City College in East Hollywood. Looking at the list of alumni there, I don’t think a single graduate of Los Angeles City College – everyone from Clint Eastwood to M.C. Hammer – has not gone on to become a megastar.

This was not, you might be thinking, the kind of upbringing that might prepare you for a career writing blues songs.

Mike and Jerry do not appear to have had much lived experience with “hard times.” But they wrote a song about them anyway, and it became a hit for Charles Brown.

Just to confuse matters they would later write a big hit called “Charlie Brown,” but that song wasn’t about him. It wasn’t about the “Peanuts” character either.

Mike and Jerry followed “Hard Times” with “Hound Dog,” a big hit for Big Mama Thornton, Elvis Presley and Doja Cat. By 1954 they were successful enough to start their own record label and sign up doowop group The Robins with whom they would create a uniquely cartoonish doo-wop blues aesthetic.

Now, The Robins would later become The Coasters – well, sort of, some of the members left, and they added some new ones – whose records Jerry once described as “a white kid’s view of a black person’s conception of white society.”

I’ll pause for a second so you can read that again and get your head around it.

The Robins records were not quite so thematically complex. It was more two white kid’s view of Black society.” Or a Black doo-wop group singing two white kid’s views of Black society. Naturally one of those songs is a cartoon blues song set in a jail. And it’s an absolute hoot! Or, if you prefer, a riot!

There are sound effects! Sirens! Tommy guns are being fired! And that’s just in the opening couple of seconds. Then there’s a Muddy Waters style, “da-da-da da-da” blues hook, suggesting that Muddy’s hook had already become short-hand for “the blues.” And there’s a slurred lead vocal that’s supposed to sound menacing but just sounds wonderfully goofy.

The slurred lead vocals on “Riot In Cell Block #9” were not performed by one of The Robins.

It’s by Richard Berry, who, as luck would have it, also played the role of Henry on Etta James’ “The Wallflower.”

He was having a moment, but no-one knew who he was. He’d later write both “Louie, Louie” and “Have Love, Will Travel,” and still no-one knew who he was. He was forever in the background, changing the sound of rock’n’roll. I guess there just wasn’t enough room for two famous Berrys in the 50s rock’n’roll scene.

“Riot In Cell Block #9” is a… 9!

Meanwhile, in Memphis Land:

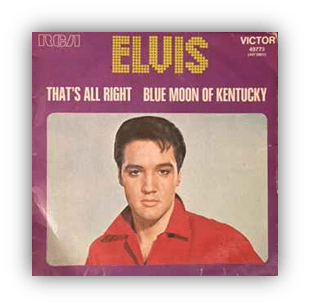

“That’s All Right” by Elvis Presley

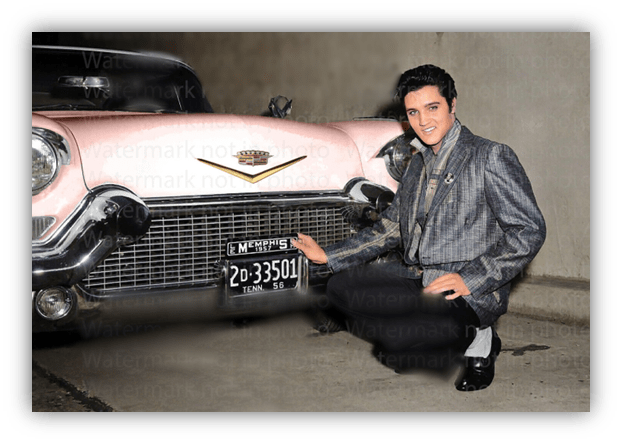

Before he was famous – and after he was famous too – Elvis was a fashion misfit. He wore loud socks. He wore bright clothes, mostly in combinations of black and pink. Elvis really liked pink.

The first time he got a royalty check, he rushed off to buy a pink Cadillac.

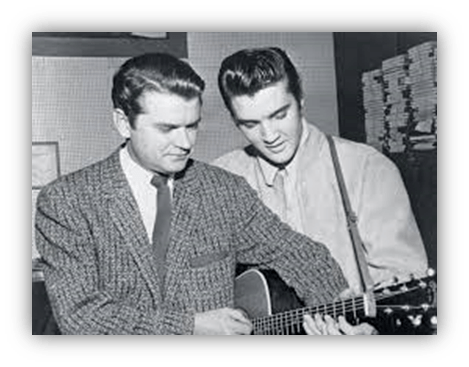

But as loud as his socks were, his personality was weirdly quiet. When he popped into Sun Records to make a record – he had no contract, but they’d make a record for you if you gave them $4 – and was asked what he sang and who he sounded like, his answers were virtually monosyllabic: “I sing all kinds”, “I don’t sound like nobody.”

Sam Philips – the owner of Sun Records – thought he sounded like a ballad singer.

Elvis would end up singing a lot of ballads. Some say too many. But the first record they put out started its life as Elvis messing around – apparently “jumping around the studio, just acting the fool” – to a decade old blues song by Arthur Crudup, a blues singer with a bunch of decent sized R&B hits in the mid-40s.

A fun blues song. With a groove. A groove that’s practically Bo Diddley. But, as you can from the record cover, it’s a groove played by a middle-aged guy who liked to sit down a lot, and possessed the stubbornly unglamorous name of Arthur Crudup.

Arthur’s version is fun and all, but Elvis’ goofing-off version is an absolute blast! It sounds like a kid bouncing across the room, having the time of his life. It sparkles with personality and confidence and swagger, and it makes Elvis sound like the coolest kid that ever lived.

Which apparently came as a bit of a surprise to the kids of Memphis, since, back in high school – and as weird as this might seem now – nobody really seemed to think that Elvis was cool. Like, at all. They were always picking on him.

They seem to have thought he was a bit of a tosser because he was always fixing his hair. Constantly combing his hair. Then messing it up so that he could comb it again. He was dressing like a Black R&B star. He was shopping on Beale Street. His favourite store was Lansky Brothers. But it turns out that buying your clothes on Beale Street – and wearing a lot of pink – was not the key to popularity in a 1950s white Memphis high school.

But they thought the record was cool.

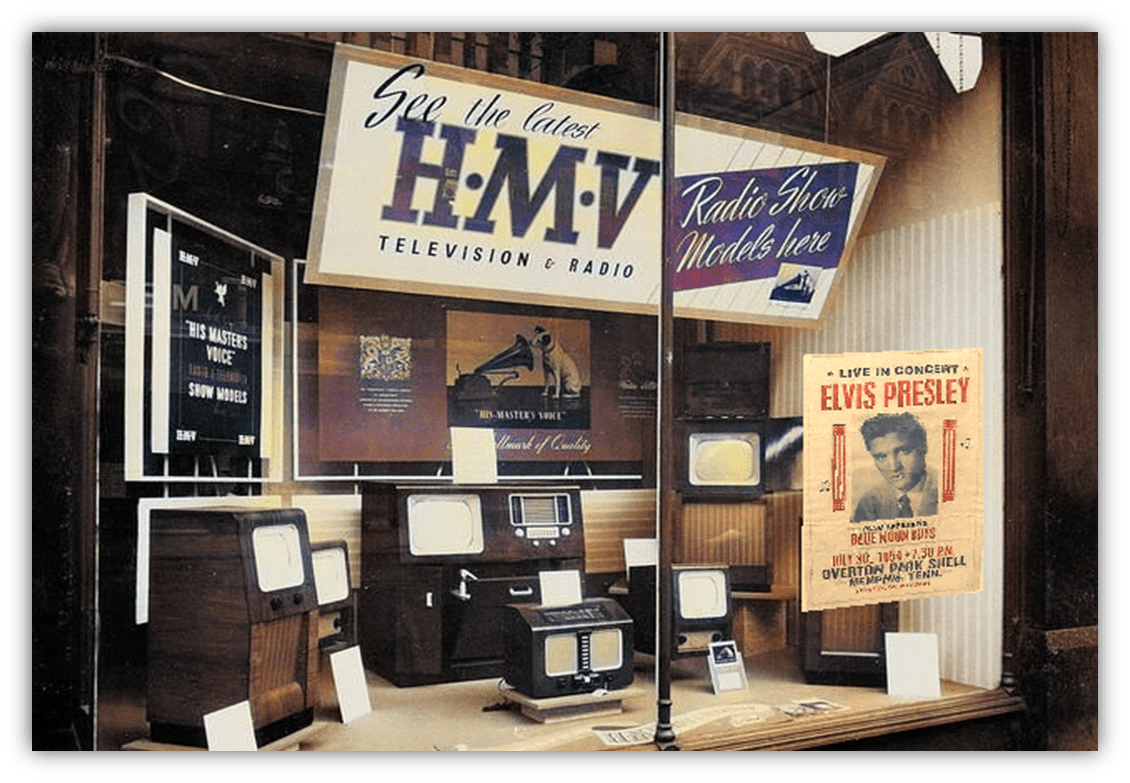

So cool that when it was played on Memphis radio for the first time, they played the thing eleven times in a row.

And got so many people calling up to find out who it was – and, it appears, particularly to find out whether he was white or Black – that they called the Presley household and dragged him down to the radio studio to do an interview straight away!

Clearly the kid had something. And his life would never be quite the same again.

“That’s All Right, Mama” is a 10.

To hear these and other 60s hits, tune into DJ Professor Dan’s Twitch stream!

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Whew! That “Sh-Boom” deep dive is an article all by itself!

I’ve wondered where the term “cover” came from but never bothered to look it up. What’s more interesting is the transition from songs that sell regardless of who recorded it to artists that sell regardless of their songs’ quality. In 1954, anything that said “Sh-Boom” would sell. Four years later, anything that said “Elvis” would sell.

Thanks for making it all the way to the end.

Oh, so it was The Crew Cuts who marketed the shampoo. Obviously. That makes more sense. Given their name and all. Good find mt58.

I strive to rinse and repeat.

Elvis’ best songs are about Kentucky… “Blue Moon of Kentucky” (a royalties gift to bluegrass legend Bill Monroe) and “Kentucky Rain” (a royalties gift to pre-fame Eddie Rabbitt).

Besides those songs and maybe one or two more, I’m not much of a fan of his music. However, my first ever pocket knife, which I still have, was an Elvis knife gifted to me by my great uncle, who was a bit of a pocket knife collector.

I grew up in Kentucky and I have an Elvis pocket knife. Maybe my limited Elvis taste was written in the stars?

Those Billboard shenanigans made my head hurt. How difficult can it be to come up with a chart that shows the biggest selling records?

Fortunately there was Riot In Cell Block 9. I haven’t heard this in so long, it’s a lot of fun. Even if it seems unlikely that a gang called The Robins could start a riot.

They were doing the best they could in a difficult environment. Founder Bill Donaldson established an editorial policy of not identifying artists by race. Billboard hired James A Jackson to write about black artists in 1919, when no black writers were being hired by national magazines.

Presumedly not too hard. But, although it seems incredible now, nobody seems to have considered the possibility that an all-inclusive all-genre all-demographics chart might be of interest to anyone.

They couldn’t imagine a time when kids might hover around the radio, dying to know what the Number One song was that week. They couldn’t imagine a time when hundreds of pop nerds might gather around a website, reading about a Number One song from decades before.

Part of the reason for that was that “Billboard” was, and still is, primarily a trade publication. It’s written for the music industry, not music fans. When it had started, decades earlier, it had sections on Vaudeville, Burlesque, Circuses, Magicians… And one of the earliest proto-charts – in 1913 – was a list of songs being performed on Vaudeville in New York, followed shortly by one for Burlesque (Alternative Vaudeville?), just so their readers could see what songs their competition were singing. There was no reason for Billboard to collate an overall chart. Why would vaudeville performers care what magicians were singing?

Things were different in the UK where New Musical Express – written for music fans – began publishing their charts in 1952, starting off with a Top… 12? Which, because it was a tie for 12th place was actually a Top 15.

It may have been NME’s success with a proper chart that led to Billboard eventually going “hey, that’s not a bad idea… we should have one of those.”

I appreciate the detailed attention to the racial divide in how it relates to the charts, and pointing out the wrongness of viewing the Popular Records chart as the sole predecessor to the Hot 100. This is still done all the time.

I missed all of last week being out of town and away from internet, but I’m glad I took the time to come back and read this,Dan! I knew some of this, but you definitely were exhaustive and filled in a lot of blanks for me, too. I think you did a great job with the delicate balance of explaining the racial oddities of the pop music scene in the 50s.

Also, you mentioned that we have a universal HOT 100 now which allows any genre to go to #1…but also, if a country star wants their song to cross over to the pop charts, they just do their own re-mix. That keeps it out of the hands of someone else doing a quick cover version.

Thanks for a good read.

If you had given “60 Minute Man” anything but a 10 I would not have been responsible for my response.