“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

Thus begins the Gospel of John.

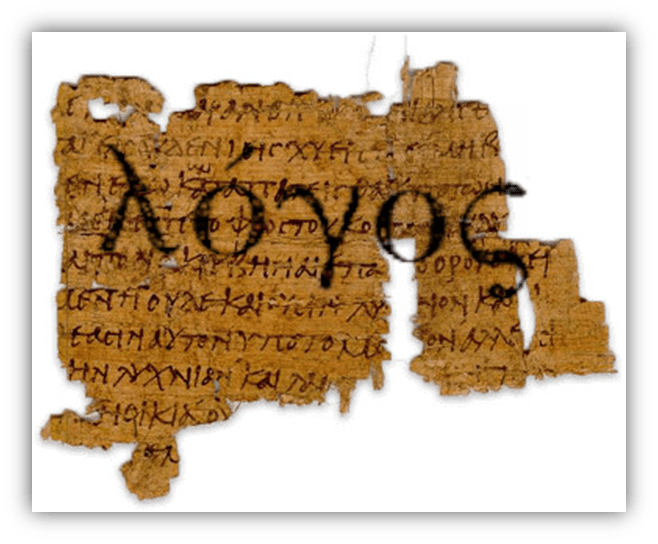

In the original Greek, the term used was “Logos,” which does not actually mean “word,” though it can mean “words,” as in speech. Taken in that sense, “In the beginning were the words” may refer to the commands uttered in the cosmic void by the Almighty to initiate His creation.

Appropriately, “Logos” also denotes a rationale, or logic, or plan.

God’s act of uttering those words manifested his grand design for the universe, putting thought into action and setting into motion the exquisitely crafted laws of the world and everything in it.

To revere Logos is to revere the perfectly articulated and expertly executed design of a higher knowledge.

Just in case you were wondering, this article isn’t about God or religion in a conventional sense.

If anything, this is about the Devil.

The anti-Logos, if you will. It’s about the spirit of rebellion and revolt, and specifically, it’s about the first wave of artists to separate themselves from mainstream society to form a vanguard of sorts to try to lead the larger culture into awakening and revolution.

I’m talking, of course, about the Romantic movement.

The first collective utterances that signaled the emergence of modern art.

In my series about Tarot Cards from Renaissance Italy, I talked a bit about the early seeds of the Enlightenment, which was a period of technological, intellectual, artistic, and political expansion in Western Europe that blossomed from around 1600 to 1800. Look to the major artists and philosophers from this time, and you will see that Logos reigned supreme.

Take for instance, the visual arts.

Starting from the Renaissance, painters used their oil and canvas to render scenes with astoundingly realistic visual details.

The proportions of the human form, the interplay of object surfaces with conditions of light and shadow, certain visual cues to elicit a sense of spatial depth relative to the viewer’s perspective—these details were depicted with increasing precision and intricacy over the centuries.

As for their content, the paintings became markedly less spiritual, and more materialistic: the Enlightenment era is most known for its photo-realistic still life paintings showing off impressive bounties, and its portraits of nobility donning jewels and furs and other treasures. This was an early era of bling, of opulence intended to demonstrate the natural order of the world, specifically the people naturally endowed to subjugate, plunder, and rule over it.

The American Revolution of 1776 was the first major challenge to that prevailing narrative of Enlightenment as manifest destiny, or at least was a major complication of it.

The principles of humanism that inspired America’s founding fathers came straight from the Enlightenment, so their founding of a government of, by, and for the people (with the potential to expand on who actually counted as “the people”) could arguably be seen as the culmination of the era’s philosophical ideals.

Still, this was a devastating disruption to imperial powers who assumed that their rule truly reflected the natural order of the world, as designed by the Almighty.

Suddenly, a prevailing rationale, or Logos, could be upended, by sheer force of will. France’s revolution starting in 1789 further strengthened the notion that rebellion was necessary to upend the order of the day for radical transformation.

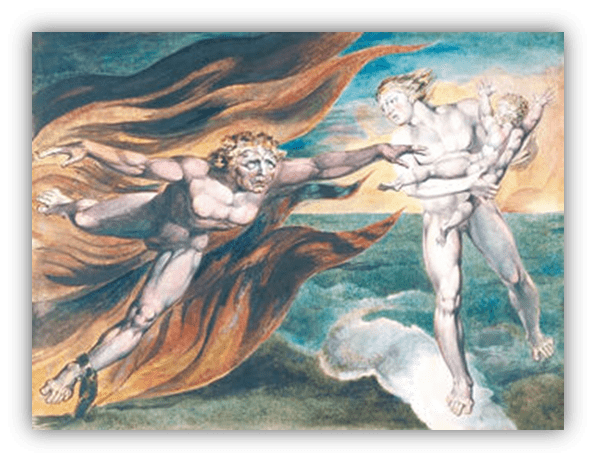

And it was around this time that a man in Britain began to independently publish writings and artwork in order to articulate and exalt the power of revolt. This man praised America’s revolution over his native empire, and he encouraged the people of France to similarly topple their ruling powers.

This man was William Blake, and he was pretty much a personal embodiment of the radical bohemian sentiment that would soon take hold of artists and writers throughout Europe, those we now call Romantics.

Blake was the son of a humble hosier, yet he came to study art at the Royal Academy. He was a sex-positive libertine who communed directly with spirits and angels.

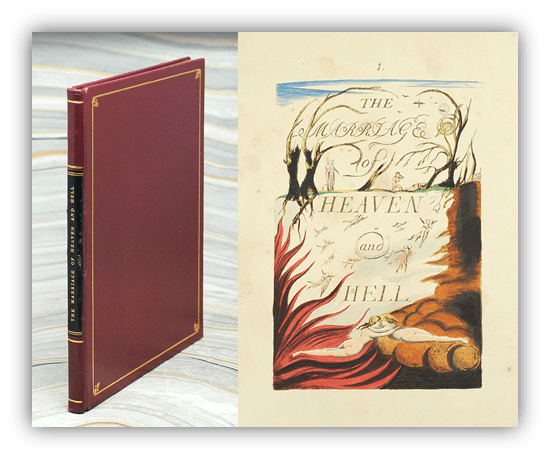

He created illuminated works resembling medieval tomes in order to espouse radically progressive ideas, calling to upend all unjust power structures, not least the bonds of slavery.

You could say that he was a walking contradiction, but he would simply say that he was a fully balanced human. Consistency and order, after all, is only half of the story.

In his 1793 work The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Blake made his outlook clear. Blake did not see the world as divided between forces of good and evil.

Instead, he saw the human soul as divided between warring impulses of order, stability, and repression versus vitality, passion, and transformational energy.

Both of these forces are venerable aspects of God’s will as well as necessary qualities of human nature, yet the forces are often in direct conflict with one another.

In accordance with tradition, Blake depicts Jesus as the Logos made flesh, the perfect manifestation of divine rationale for the sake of cosmic order. But while Logos is an essential part of who we are, so is anti-Logos. Thus Blake also exalts Satan, the first rebel according to the lore of his time, as an equally essential component of God’s nature, and of ours.

Contention, conflict, and even violent revolt are sometimes necessary for God’s true will to unfold within a society, which constantly struggles to reconcile its dual urges for order and for progress, for stability and for transformation.

And since the Enlightenment had pushed so hard for the prominence of Logos in the Western world and their colonies, a countervailing force of anti-Enlightenment was needed to really shake things up.

In other words, Satan deserved his time in the spotlight.

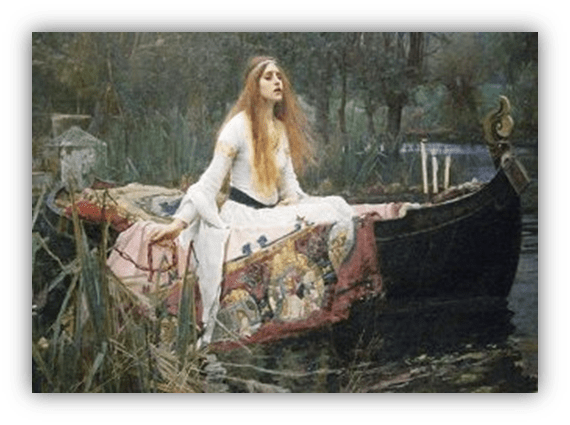

In the decades that followed, more writers and artists followed in Blake’s footsteps.

There were Byron, Goya, Wordsworth, Radcliffe, Coleridge, and later on: Hugo, Bronte, and Baudelaire, among others. These people centered their works on irrational passions rather than on order or human reason. They elevated awe for the supernatural over knowledge used to strip the world of its mysteries.

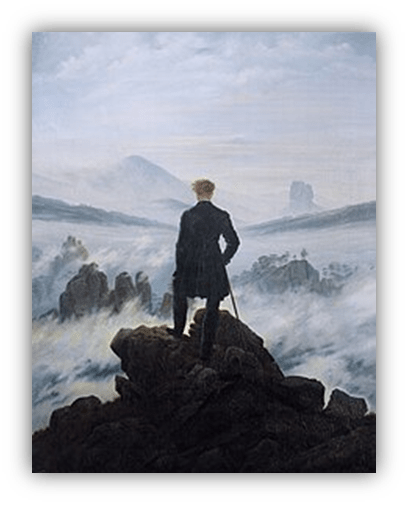

They decried the expanding sea of loud, filthy, overcrowded urban districts imposed upon them by rampant industrialization, and instead praised the simple beauty of nature.

They venerated rogues, rebels, and openly flawed humans whose main virtue was the exercise of their liberty, or simply speaking truth to power. Rather than calm or uplift the public with works of pleasing beauty, the Romantics sought to shake audiences out of their complacency.

The role of artists was not to placate or to pander, it was to challenge, to wake people up and tune them into the raw, incomprehensible, transcendently beautiful messiness of life.

I mentioned the term “vanguard” earlier.

(Or maybe you prefer avant garde, you French elitist, you,) which is a military term implying a forward march, wherein a small band of brave souls situated at the front of the pack leads the way ahead.

Given their disdain for rampant materialistic exploitation, I doubt that the Romantics would have thought of themselves as a vanguard per se. If anything, they wished to shake society out of its forward march rather than lead the way ahead.

Still, the Romantic view of life and human nature as inherently contradictory is a thoroughly modern one, one that we all still wrestle with.

And whether they liked it or not, the Romantics did in fact serve to inspire later groups of artists who openly considered themselves to be the vanguard of culture, and whose work could be readily labeled as modern art.

So, the vanguard of the vanguard? Probably not the legacy that they were hoping for, but the engines of progress churn on with or without us and do what they will.

Coming to these works some two hundred years later, we won’t find them nearly as radical as they were originally seen.

Still, their impacts on our culture were deep, and are felt even today.

Love stories featuring a cynical yet sympathetic anti-hero?

Or a badass hero who typifies rugged individualism?

Have a taste for gothic horror?

Maybe some overt displays of sex, drugs, and rebellious decadence? Or maybe just some clamorous musical movements to add drama to whatever it is you’re watching.

For any and all of these, be sure to give thanks to the dark lord Satan, and the anti-Logos he represents.

Or, at the very least, maybe raise a glass of absinthe and give a toast to the Romantics, whose libidinal, brave, revolting, and darkly beautific passions still churn through us today.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Great opening to the series — I’m hooked already! The Romantic period is definitely a lot more up my alley…

Nice! I knew there was a more effective way to shovel Bible verses into my articles…

Great stuff as ever.

It’s interesting to consider how the Romantics would have been viewed at the time and how they are now in their homeland.

William Blake’s most recognisable legacy is Jerusalem which has been adopted as an alternative national anthem. It gets played at some sporting events in place of God Save The King. The fact that the orchestration by Hubert Parry and then Edward Elgar make for a much more rousing tune than the official dirge certainly helps though I can’t imagine what Blake would think of his words being co-opted into rampant patriotism.

Byron and Shelley have a legacy as the rock and roll stars of their day, living fast and dying young. Whereas Wordsworth is seen as romantic in a negative sense, outdated and reduced to two lines about wandering lonely as a cloud and finding some daffodils. Though at least in his case its the poetry people remember rather than his lifestyle.

Somehow I feel that Byron, Shelley, and Wordsworth would all be happy with their legacies.

Oh, my comment was lost!

tldr: I think Americans only know Blake through references via pop culture. I myself only got into him from Alan Moore and Philip Pullman.

I didn’t know that about Jerusalem. Listening now, it’s a pretty song. I doubt Blake would like the blind nationalism. I’ll be touching on that phenomenon relatively soon, via another iconoclastic prophet figure.

Here they talked of revolution

Here it was they lit the flame

Here they sang about tomorrow

And tomorrow never came

“You’re always a day awaaaayy….”

Oh sorry, wrong musical.

Well, now I’m in the mood for a showtune:

14 weeks on the Billboard Hot 100, peaking at #13 position… 51 years ago this month:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cSs3mr3C4pA&list=PLVPcx1ubmgzeqn3YTE2wNnMSPPG8gHHRY&index=3

Thanks for another expansion of our knowledge base, PofA. Flipping through Blakean-adjacent Wikipedia pages, I see that in Infinite Jest, David Foster Wallace made a flippant reference to The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Blake’s reach truly does reach into the contemporary.

Yeah, pop culture is riddled with Blake references.

Aldous Huxley named his autobiography The Doors of Perception, and Jim Morrison named his band after one or both of those.

Party Monster uses the great quote “the road of excess leads to the Palace of Wisdom.”

His painting was used in the movie Red Dragon for the titular mythical beast.

I guess “The Tyger” is a fairly famous poem in its own right, but the first time I encountered it was via Batman: The Animated Series!

“Cinema is king.”

-Francois Truffaut in Day for Night

That’s French New Wave elitist.

Damn you, Jean Luc Godard for making Agnes Varda cry.

Varda is the reine.

I’ll get to those snooty French films at some point! 😉

“That’s the movie you wanted to see?…Had to read the whole [insert curse word] movie. [insert curse word] subtitled. Some guy from a road crew recommended it to you, a [insert curse word] subtitled movie?”

-Amy Adams in The Fighter

You have to tell me if Amy Adams’ Massachusetts accent was accurate or not. How could I possibly know? She lost to costar Melissa Leo in the 2011 Academy Awards. [insert curse word] Watching Belle Epoque through her character’s eyes was a whole new experience. I was laughing at things that weren’t meant to be funny.

In my mind, the date scene in the David O. Russell film is a classic, but according to YouTube, it’s not.

My poetry seminar professor told our class that Andrei Tarkovsky once said that watching a film should be a torturous experience. She explained how Tarkovsky wanted no special effects in Solaris. He thought Solaris was too Hollywood. Holy crap.

Godard is homework.

Truffaut’s films have warmth.

Spielberg’s The War of the Worlds, to me, is the absence of Francois Truffaut’s life on this mortal coil.

I have comments related to your excellent essay.

I got sidetracked by that line.

Thinking about what constitutes an art film in the 21st century is, admittedly, snooty.

Dude, if only my college semester of Humanities had been a tenth as interesting as this article was Phylum, I might not have dreaded it so much for 4 months.

Very intriguing topic! I’m curious to see where this journey takes us this time….

Thanks!

I think a major problem with the Humanities is that there aren’t nearly enough manatees. Wouldn’t that be more interesting?

I will try to rectify that.

One of the handful of things I loved about living in Florida – going to Blue Springs in January and February to see all the manatees congregate in its warmer waters off the St John’s River. And squealing when spotting a baby manatee. Love those creatures.

One time I was canoeing with my family on the St John’s near Blue Springs, and we encountered a rather active manatee pod. They were splashing around and playing like a dolphin pod, it was amazing to actually witness.

Humanity would most certainly benefit from more manatees. 🥰

I’ve never been to St John’s but Weeki Wachee Spring closer to Tampa is absolutely gorgeous. With plenty of manatees if you time it right.