By the late 1800s, European artists had a powerful new rival to contend with.

Over the last few centuries, painters had placed increasing emphasis on realistic visual details in the scenes they depicted, and thus provided a means to accurately represent the people and events of the surrounding world.

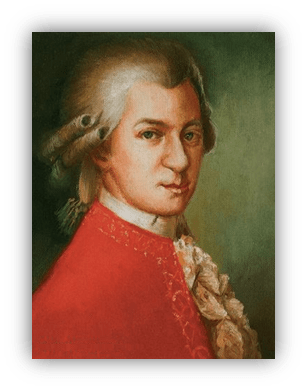

We have a good idea of what Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart looked like, purely based on portraits of him that were painstakingly realized by expert craftsmen using oil on canvas or ink on paper.

Through their portraits, landscapes, and historical pieces, artists could thus bestow to their subjects the gift of immortality.

But once photography emerged as an easier and more reliable way to capture a scene, painters and illustrators lost their authority as the gatekeepers of visual records.

Suddenly, there was a new wizard in town.

What were the fine artists of Europe to do in this new environment? How would they command the respect of the public? To circumvent the redundancy imposed by the Kodak camera, many painters ultimately turned to…Fuji…for inspiration.

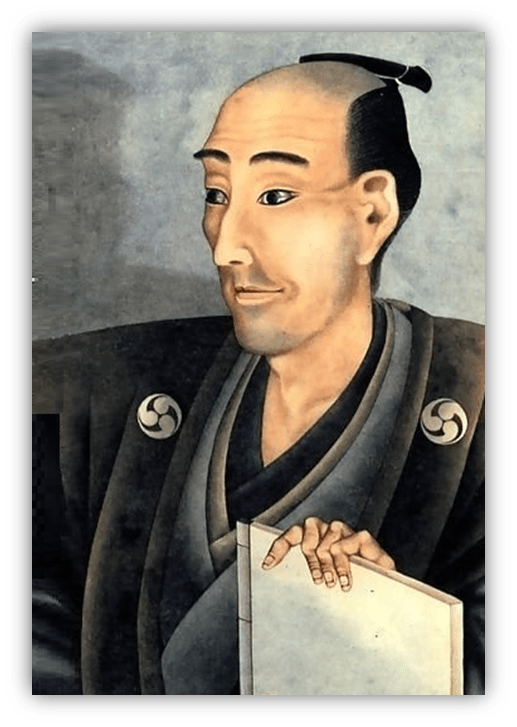

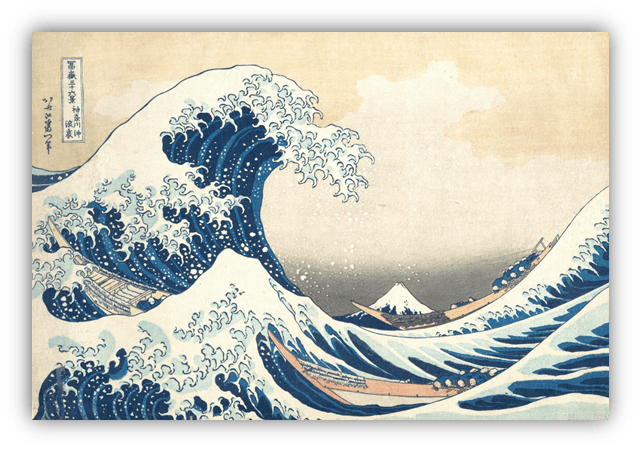

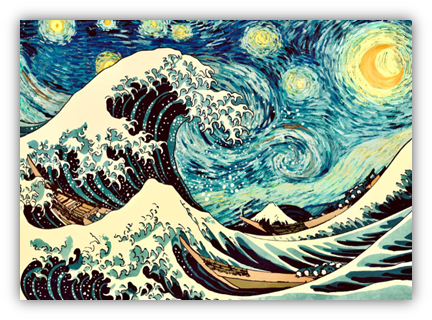

Hokusai, 1832

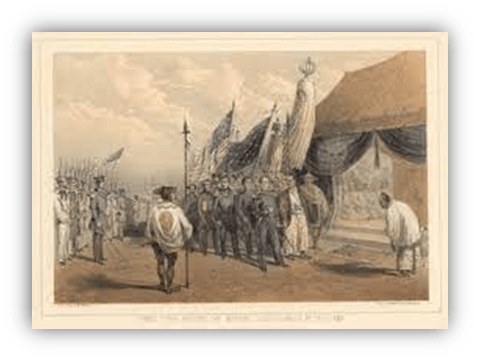

On March 8th, 1854, Commodore Matthew Perry set foot on the shores of a forbidden land.

His thinly veiled military threats against the surrounding towns proved effective, and the nation’s de facto ruler, the shogun, soon met with Perry to charter a treaty that would open Japan’s ports to trade with the United States.

This action officially put an end to a two-hundred year period of isolation, and led to a flood of trade with foreign powers such as England, the Netherlands, and France.

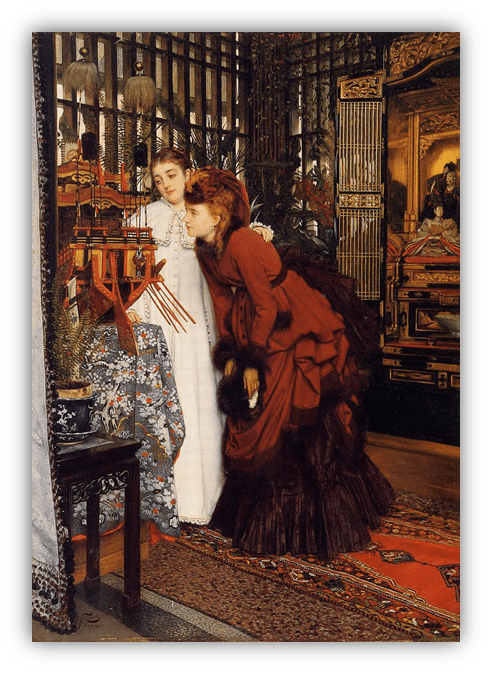

Shortly thereafter, Japan began its slow process of modernization. And all across Europe, people became enamored with the silk kimonos, folding fans, samurai swords, paper umbrellas, decorative plates, tea sets, woodblock prints, and other exotic treasures from the newly opened empire.

Some of these elements eventually found their way into European paintings of the time, though the earliest examples were just superficial touches, more like cosplay than anything truly inspired.

Monet was clearly a fanboy.

But eventually, some key painters would look directly to Japanese artwork for ideas about linework, figure drawing, coloring, perspective, and many other aesthetic considerations for visual representation. The most important sources of inspiration were woodblock prints, known in Japan as “ukiyo-e,” or “pictures from the floating world.”

The earliest ukiyo-e prints focused on depictions of famous kabuki actors, pretty geishas, or erotic scenes from the pleasure districts, and the term “floating world” was a Buddhist reminder of the transient and worldly nature of such distractions.

More importantly, there was a class distinction to be made. Unlike watercolor painting, which was reserved for the nobility, woodblock prints were not considered elevated or refined. They were regarded as commercial fare, bought and collected by merchants.

Despite its lowly origins and relative availability, ukiyo-e art eventually matured into a visually impressive art form, mostly due to the innovations of the great illustrator Hokusai.

Hokusai transitioned from celebrity portraits and advertisements to intricate landscape designs, and scenes of life and culture throughout Japan.

He was followed by Utamaru, Kuniyoshi, Hiroshige, and other legends of illustration who continued to elevate the form.

Hiroshige, 1857

Late 19th century European art is famous for the emergence of several artistic movements exhibiting a dramatic departure from conventional visual representation.

- Impressionism took the slice-of-life documentation approach of Realism, yet the scenes were conjured with dreamy pastel tones and dazzling textures that evoked our subjective impression of shadow and sunlight.

- Expressionism was similarly Realist in content, but its bold lines, crude dimensions, and globbed textures were employed in pursuit of a childlike, primitive invocation of deep feeling.

- Art Nouveau showcased flat perspective and clean lines for an intricate, highly decorative form of commercial illustration.

What do these works have in common?

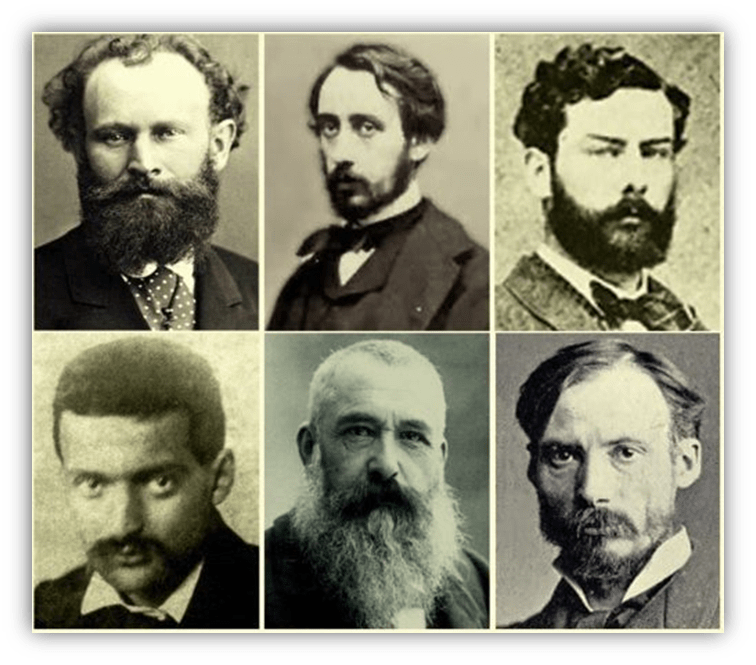

Think of any major late 19th century painter:

Monet, Manet, Renoir, Degas, Toulouse-Latrec, Beardsley, Van Gogh, Munch, Klimt.

You’ll find that Japanese art was a foundational influence for them.

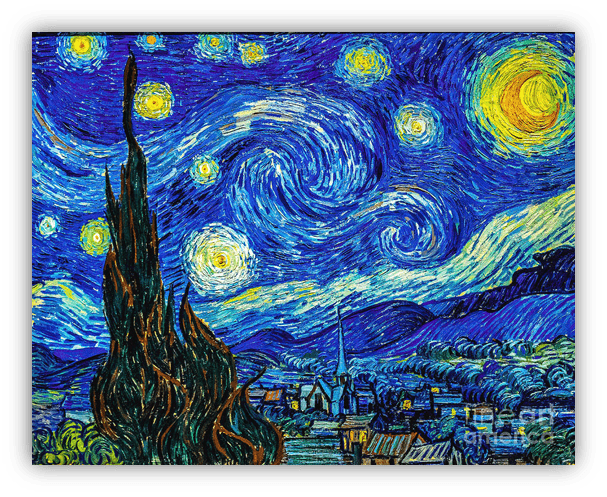

Vincent Van Gogh didn’t mince words: “All my work is based to some extent on Japanese art.” Even Gustave Courbet, whose influential Realism landscapes inspired the shift into Impressionism and Expression, these were themselves inspired by Japanese watercolor paintings and ukiyo-e prints.

Indeed, the woodblock printed images of ukiyo-e really made their mark on the minds of Western artists everywhere.

The sure lines and the bold colors. The occlusion of the background by objects in the foreground. The avoidance of the center as the main point of interest. The “floating” perspective, as if the viewer were a drone flying low and facing down onto a scene.

This wasn’t just a random kimono or a folding fan appearing in a scene; this was outright devotion. And as such, this collective moment of “Japonisme” was a true fusion of styles for something completely new.

Van Gogh, 1889

That’s all well and good for the visual arts, but what about music?

Did the Japanese aesthetic resonate with European composers?

Admittedly, most of the references to Japan around this time were superficial exoticism, such as Camille Saint Saens’ 1872 opera, unfortunately titled “The Yellow Princess.” But was there something more like true fusion, like musical Japonisme?

The most prominent example to me is Claude Debussy.

Nowadays, Debussy is often likened to a musical version of Impressionist art- a comparison that irked the composer quite a bit.

Interestingly, Degas himself hated being called an Impressionist painter, yet he and Debussy both expertly conjured the delicate, contemplative beauty of Japanese aesthetics in their own works. So maybe that’s the connection that resonates with the public.

Debussy’s piano music is like watercolor painting put to sound: somber, meditative, spacious, and fairly static. They are mood pieces rather than musical narratives.

One of his more dramatic orchestral works, La Mer, was inspired by Hokusai’s most famous print, The Great Wave.

The drama comes not from a story, but from a natural scene: the music is structured to churn and break like the waters, taking listeners into uncertain and sometimes frightening territory.

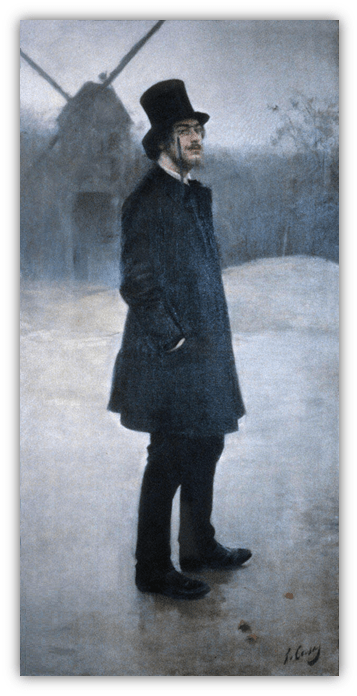

There is also Erik Satie, who mostly composed for solo piano.

Satie’s work is even more minimal than the most minimal work of Debussy, who he befriended in 1890. More sketch-like in design, more grounded in open space, and more repetitive. Works like his “Gymnopedies” are almost like rendering a haiku into musical language.

I don’t have hard proof that his work was directly influenced by Japonisme in the same way that Debussy was.

Given the nature of his music, and the larger cultural context of the Paris art scene in the 1890s, I would be very surprised if the seeming connection was nothing but mere coincidence.

Though I’m a huge enthusiast of international art and cross-cultural fusion:

I must say that the earliest examples of such things in Western history are often quite…problematic.

There’s no shortage of styles that were plundered and thoroughly enjoyed by a dominant elite, all while caricaturing the plundered culture as primitive or beastly. Certainly some of the Japanese content in 19th century Western art had an air of superficial exoticism to it; a fascination with the new Orientalism du jour.

But Japonisme was something different.

This was the rare instance of mutual respect among independent powers, and of certain artists in the West deeply revering the work of Eastern masters.

This was two worlds of humans coming together, drawn by a common understanding of life and of beauty.

Subsequently, the influence went both ways, with Impressionist and Expressionist art becoming quite popular in Japan.

The newly opened nation would continue to modernize in its own unique way, with European culture being the dominant external cultural reference up until World War II.

And the impact of Eastern art on the Western avant garde was only just beginning.

We’ll surf those waves soon enough.

…to be continued…

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

I used to have a poster of Hiroshige’s The Plum Garden in Kameido. I didn’t even notice the humans in the painting until the 3rd or 4th time I looked at it. I think the painting has its priorities straight — nature is beautiful and powerful and man’s rightful place is but a speck in its existence.

Mrs. Pauly and I just finished binging Burn the House Down on Netflix. I don’t necessarily recommend the show… a very melodramatic Japanese production. But the food, the clothes, the whole aesthetic of Japan the show presented was very eye-opening and comforting. We have a lot yet we can learn from our neighbors to the East.

I never heard of “Burn the House Down,” but if it’s in Japanese, my wife will want to watch it!

It is in Japanese, and I believe it’s a fairly recent Netflix addition. Started off kind of intriguing, but by the end the melodrama was telenovela-level.

I know what Japanese melodrama looks and sounds like. Also, I remember the melodrama between my grandparents as in regard to the superiority of K-drama over J-drama, and vice-versa. I keep repeating myself, but I can’t get over the crossover of Asian National entertainment into the mainstream. I literally dropped my EW when I saw a full-page article on K-dramas.

Also, Japan(and sometimes Korea) can learn something from their neighbors to the west about melodrama by watching Douglas Sirk.

I really didn’t get impressionism, and everything since, until my art history professor talked about how photography changed everything. Then, very suddenly, I understood it all. Thanks for renewing my knowledge!

I never realized the full influence of Japanese art on the European world – when I taught the Impressionist period, I simply told my students to remember that photography changed the rules of the game. This was very enlightening!

I was the same way. Then, in my recent trips to Tokyo, NYC, and Lyon, I went to several art museums with Impressionist and Expressionist art, and was struck by how much I could relate to Japanese art. So much so that I looked into the scholarship, and found that Japonisme was very much a thing, one of the defining things for those artists, in fact. Pretty neat!

I won’t shame myself by revealing that when you asked what the works had in common, I looked at the photos of the six artists and thought; facial hair. Oh…..

Seriously though, this has been such an insightful read. It’s the art equivalent of Bill’s Friday music classes. I’d never considered the historical context of the opening up of Japan and the influence that had on European art. Its obvious now you’ve pointed it out.

Need to visit some galleries to put this insight to use. Off to Italy in four weeks, staying near Pisa. We’re aiming to get to Florence for the day and visit the Uffizi gallery – thats if the infernal heatwave relents otherwise I’ll be basking in the pool trying not to combust. I know that focuses on the Italian renaissance rather than this period but looking forward to the experience.

Ah, jealous! I’m sure you’ll see some fantastic stuff. Maybe even some early esoteric works if you have an eye for it…

The Uffizi is awesome! And you’ll find all the gelato you need to beat that heatwave.

OMG, too funny Chuck. Of all the things we saw in Florence, my friend was most impressed with the size of the gelato’s. It was hysterical. I had to take a picture of her looking totally gob-smacked at the Gelato she had purchased. So funny you mention that!

Ooh, fun JJ! That’s where my friend and I stayed on our Italy trip, a trattoria in Tuscany. Dumb luck we chose to visit Siena the day before the Il Palio horse race. We were eating lunch at a place on the Piazza del Campo and wondering what the deal was with all the flags and grandstands and pomp everywhere in that square. Kinda wished I’d known about it before our trip so I could have appreciated it more, but oh well.

Didn’t make it into the Uffizi, but we did the Il Duomo tour at the Florence Cathedral. The kind of seeing is believing trek up through the dome itself, quite a trek to the top, but the views’ amazing.

Have fun, we expect a future multi-chapter entry of your travel experiences upon your return!

The Vincent Van Gogh quote totally floored me. I have to pick my jaw off from the floor. Like, wow.

Shout out to mt58 or whoever did the Hokusai/Van Gogh, Great Wave/Starry Night mashup. It’s pretty great.

That was indeed mt, and it is perfect!

He’s good at this stuff it seems…

*CASTING DECISION SPOILER ALERT* Is David Lynch(as John Ford) referencing the “floating world” in The Fablemans, when he explains to a young Spielberg that when the horizon is at the bottom or top, it’s interesting, and when it’s in the middle, “it’s boring as ****”?

I certainly thought of that when I was watching it!

Wait, really? All that Japanese art I’ve always been drawn to my entire life had a name associated with it, and it influenced a multitude of 19th century western artists?

Well, I’ll be!