“Oh great star! What would your happiness be if you did not have us to shine for?”

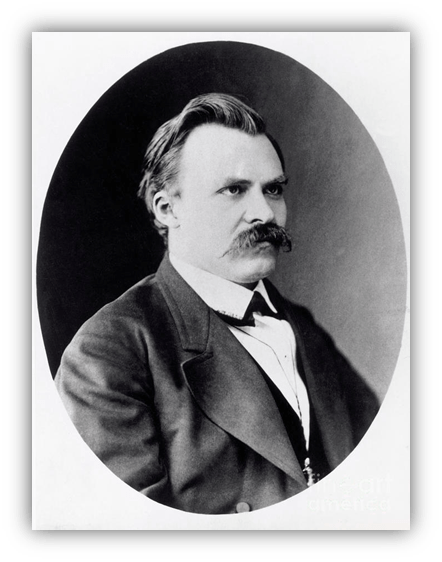

Friedrich Nietzsche

Thus Spoke Zarathustra: A Book for All and None- 1886

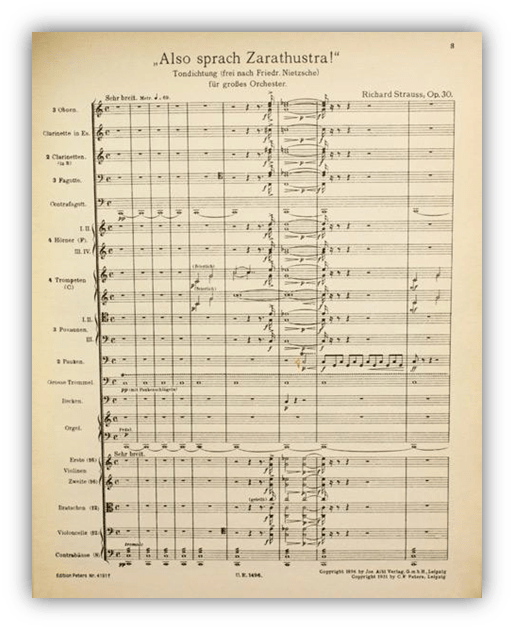

In 1896, Richard Strauss completed his orchestral tone poem, “Thus Spoke Zarathustra.”

Everyone these days will recognize its opening section, even if they don’t recognize the work’s title or its composer. Over the years, the theme was used by…

Stanley Kubrick for 2001: A Space Odyssey

by Elvis Presley for his stage entrances…

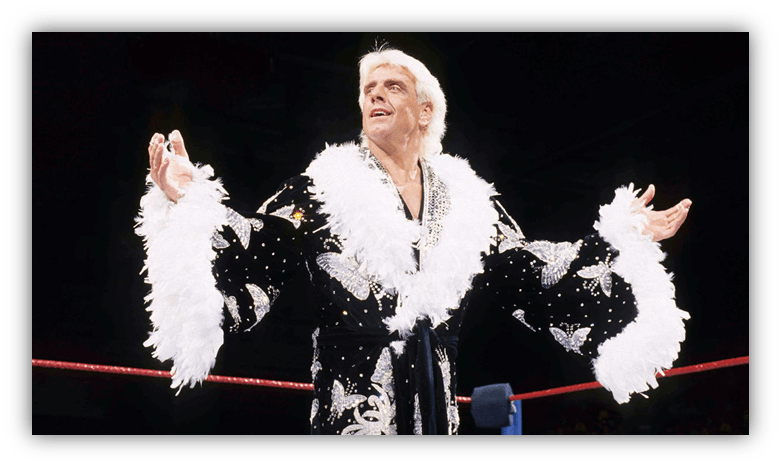

and by the wrestler Ric Flair as approached the ring.

Among many others.

The piece has since become cultural kitsch, an easy way to signify and lampoon an air of dramatic significance or self-importance.

I wrote a while back about how “getting” a work of modern art is often a sort of perceptual trick, like seeing an image of a Dalmatian emerge from what had seemed to be random splotches of ink. So too with the compositional music of Europe in the late 19th century.

If you’re not listening with the right ear, what you hear can sound obnoxiously grandiose, and/or just plain silly.

But if we want to better understand the intention and the significance of these works, we need to listen more carefully.

So, some context:

Strauss wrote “Zarathustra” as a musical rendering of a book by the same name, written by the philosopher Frederic Nietzsche.

In his score, Strauss attempted to capture the broad strokes of the story, a fictional account of the ancient Persian prophet and founder of Zoroastrianism. Nietzsche’s story was a “sequel” of sorts, in which the legendary man who once divided the whole world into forces of good vs evil now tried to understand the world in a more modern context.

Over the course of 30 minutes, Strauss’ piece evokes Zarathustra’s struggles to find meaning and purpose in the face of an indifferent natural world.

After religious tradition and science fail to provide ultimate meaning, the prophet eventually finds consolation in small moments of dance and laughter.

Yet the piece ends with unresolved tension, highlighting the uncertainty and ambiguity that continues to persist even after existentialist enlightenment.

Heavy stuff, to be sure, and radical for its time.

Musically, Strauss built on the innovations of Richard Wagner, the late great composer who had advanced exciting new ways of heightening emotional drama and tension in his opera scores.

Strauss’ father had forbidden him to study Wagner as a youth, but he came to revere the rising titan as a major inspiration for his own rebellious music.

Many musical historians today point to Wagner’s opera Tristan and Isolde as the most significant seed for what would later become modernism.

Strauss’ “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” was a musical tribute to this innovator, following in his footsteps in the hopes of attaining that same ecstatic grandeur.

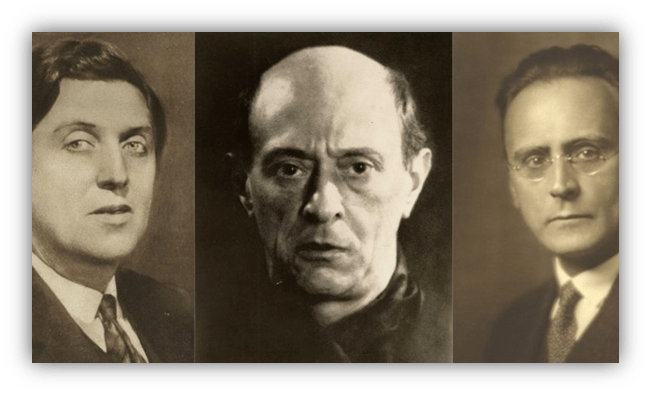

Strauss’ celebration of Nietzsche and Wagner together in the same piece is itself extremely interesting, because the two men had once been friends.

Nietzsche, too, had looked up to Wagner as a sort of rebel father figure. He had believed that Wagner’s music held the power to wake people up and transform society for the better.

That is, until the two men grew apart, and never reconciled.

Wagner passed away in 1883, and a few years later, Nietzsche published several essays denouncing Wagner’s works as embodying the decadence that ails modern society, the very sickness he sought to rise against.

It was the last work he published before his complete mental breakdown, brought on by syphilis. Talk about unresolved dissonance!

At the heart of their break was a fundamental philosophical difference about German identity, and what it meant for the future of society. After the French Revolution, and especially once Napoleon Bonaparte began to expand the French empire, the sense of national identity surged dramatically among territories under threat, Germany included. Over time, Richard Wagner came to advocate for this more strident German nationalism. Nietzsche attacked such mythic traditionalism as perpetuating the problems of modernity rather than finding a way out of the trap.

To some extent, Wagner’s position had changed over time.

Both men had once dreamed of revolution for societal transformation. Wagner had even taken part in the 1848 uprising in Dresden, yet this effort ended in failure. He lived in exile for several years as a consequence, and his ballooning debts during this time no doubt colored his desire for more practical and lucrative applications of cultural influence.

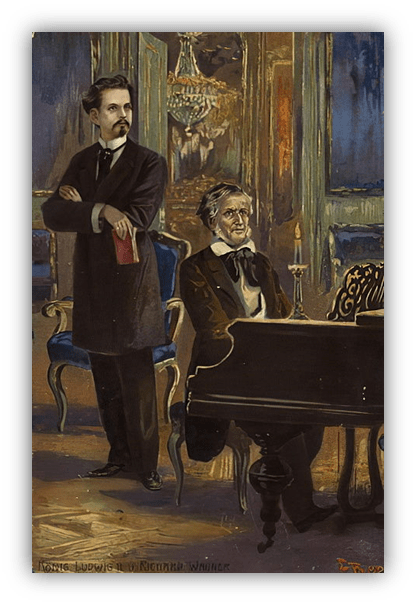

When the newly crowned King Ludwig II offered to be his benefactor, Wagner happily complied. He would start to make some of the most musically radical operas of his career—such as the Ring cycle, and Tristan and Isolde—while at the same time living more and more as part of Germany’s institutional elite.

While Nietzsche raged against the machine, Wagner became part of the machine, hoping to tweak and retool from the inside, thinking more and more about how to make Germany great.

Nietzsche himself dreamed of a pan-European identity, a global culture where the most brilliant thinkers and artists (his idea of “supermen”) have the freedom to inspire and advance the larger culture in meaningful ways. Such a solution was never practical, of course, and it existed more as an aspirational stance than any real proposal. In some ways, Nietzsche re-articulated the revolutionary utopianism of the Romantic movement, but in other ways he foreshadowed the existentialists of the 20th century.

As in: we may be powerless to stop the societal systems and cultural forces we find ourselves in, but even if that’s the case, we have the responsibility to try and try, to never give up.

And his diagnosis of modern society was truly on point.

Scientific progress and technological advancement had indeed led to a widespread disenchantment with the natural world. The decline of religion in modern society was leading to a growing sense of meaninglessness. Mass culture provided cheap and easy entertainment to distract people from their problems, but not to help them grow or heal.

Even if he didn’t have a practical cure to offer, he could confidently determine what was a meaningful change in society versus more of the same sickness. To him, German nationalism was just more decadence, more sickness, more spiritual rot.

Wagner wished to elevate the people of Germany with his musical narratives, but Nietzsche was convinced that this path would only make things worse.

History proved Nietzsche right, but in the worst possible way. The works of Wagner and the works of Nietzsche were both used in the early 20th century to stoke aggressive German nationalism, and the rise of fascism. Just as Nietzsche had used the ancient Zarathustra as a mouthpiece for his own ideas, his sister and Adolf Hitler bowdlerized Nietzsche’s writings and used them to advance their National Socialist agenda.

Even when one tries to escape the system, the machine cares not.

The unresolved ambiguity of Strauss’ tone poem for “Thus Spoke Zarathustra” is in many ways perfect for Nietzsche’s take on life, as we never know quite where life, and especially modern society, will take us.

Yet for me, there is a more important work from around this time to consider in order to understand the real power of late Romantic art.

A work that seems to perfectly embody Nietzsche’s aspirations, even more so than Strauss’ thoughtful tribute. Like “Zarathustra,” this music was deeply informed by the innovations of Wagner, but taken to such extremes that it still sounds unsettling to us, even now. It’s a piece that is not just inspiring, but deeply challenging, cathartic, and thus transformative:

This is Gustav Mahler’s second symphony, which was completed in 1894.

Mahler enjoyed fame as one of the world’s finest conductors, but he was largely unappreciated as a composer during his life. Part of his struggles had to do with his Jewish heritage, though it was mostly due to the radical maximalism of his compositions. It was only many decades later that he started to enjoy popular acclaim as one the last great Romantic composers, though still not for the larger public.

Mahler lived a life filled with personal pain and misfortune, yet he strove to make the best of his time on earth, and to elevate the culture around him.

His second symphony is a long, loud, and astoundingly complex work, requiring quite a lot of patience to endure. It’s a torrent of roiling emotions, with the dread of death aggressively pervasive throughout.

But those who sit through the whole performance come out of it transformed, and improved. At least for a moment, they can stand defiant in the face of death, and exult.

Nietzsche would have been proud, even if this man was advancing Christian sentiments. Wagner would have been jealous, and resentful that he was bested by a man thought to be of lesser stock.

Several young composers of the time were listening attentively, such as Alban Berg, Anton Webern, and Arnold Schoenberg.

They would later develop what we would call Modernism proper. While it’s sometimes tempting to lump all of these more avant garde musicians together as “difficult,” the central difference is that the later composers had no concern for what the public may have thought or felt about their work.

Mahler demanded a lot from listeners, but he cared very deeply about how his music affected his audience.

His work will never be easy entertainment, but it makes for some potent therapy.

Like Nietzsche’s esoteric rants, this is art that exists on its own terms.

But it’s also there to guide anyone willing to make the effort.

To help them brave uncertain terrains, to confront the anxieties and uncertainties that we all have, and often try to avoid.

To make some sense out of our confused and confusing time in this rapidly changing world.

We don’t know where our lives will take us, but we can use the time we have to live those lives to the fullest.

As for me, I’m going to exult in the dazzling beauty of the great stars out there that shine for us.

All the better if I can convince others to do the same…

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Amen!

Sorry for the spoiler…

Good job, Phylum! And you saved me from writing “What Makes Romantic Romantic?”

Maybe you can answer a question I’ve had for a long time. So much of philosophy is about man’s search for meaning. Why do we need meaning? Is it egotistical of us to assume there’s some deep meaning behind life, the universe, and everything? Horses and elephants and dogs don’t look for meaning. Only humans. Can’t we, like the other animals, just be?

“Can’t we, like the other animals, just be?”

Not easily, and it’s our blessing and our curse. I love the intro chapter to Karen Armstrong’s The Case for God for detailing how it’s our blessing, our nature as homo religiosis. But being a hyper-social, self-aware primate has its drawbacks (see Robert Sapolsky’s Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers for the curse side of things), and the search for meaning is one way to deal with these anxieties.

Is it egotistical for us to assume there’s deep meaning behind life and everything?

Certainly some of the stories we cling to for meaning can be egotistical. As for the general phenomenon, though, I think of it as egoistic rather than egotistical. Not necessarily a bad thing, it just reflects the only way we can make sense of the world, through our own experiences.

As for Romanticism, I can’t cover music from a technical perspective. So I await your astute musicological insights there!

Oh, to be a zebra, eh? Of everyone I ever met, most balanced, the happiest, and the one that tried the hardest to make people happy, was my golden retriever. I strive to be more like him.

Enlightenment:

❤ ❤ ❤ “I think I’m in love.”

“Religion is the smile on a dog” – see, Edie Brickell knew.

“Philosophy is the talk on a cereal box.”

There is this scene in The Lady in the Water that suggests M. Night Shaymalan knows who Edie Brickell is.

A child, an oracle, sees secret messages in a host of cereal boxes. I miss this period in Shaymalan’s career when he obviously had final cut. I just went along with wherever his muse took him. e.g. “Swing away, Merrill,” in Signs. He took chances, and risked ridicule.

French critics like The Lady in the Water.

This Black German Shepherd is incapable of looking bad in a picture. He’s always “on”. My rescue looked different at this age. This is not the east German line, or is it? If I send this to my mother, she’ll cry. You have a great dog.

My Black German Shepherd’s timeline overlapped with the death of my father and my maternal grandmother. I was able to keep it together because Lucky to hug. When he died, it’s as if I really felt the loss of my father and grandma for the first time.

A reverent skyward hat tip to your loyal black German Shepherd.

My own dog is a mix of various Asian breeds: Jindo, Chow Chow, and Japanese Chin. And she’s actually full-grown; she already had two litters of pups before we rescued her. Pup in appearance, graceful lady in demeanor. Aside from sniffing the ground for pee, of course.

Whoops. All my dogs are/were male. I have this annoying habit of presuming all dogs are dudes. My friend has a golden retriever. When I saw his dog do his duty for the first time, I told him: “Oh, look. Basil pees like a girl.” My friend responded: “Brah. Basil iz one girl. Dat’s why, cuz.”

“Is she named after Tony Basil?”

“What?”

As it turns out, Basil has a sister named Olive.

I looked up all three breeds. I never heard of Jindo and Japanese Chin. Was the mix intentional, like a golden doodle, or just a wonderful convergence of three breeds? Because your dog is one pretty lady.

I doubt it was an intentional mix, as she was a village dog, born on the streets of Donghae, South Korea. Jindo is a popular dog in Korea, and yet (like in Japan) abandoning mutts is unfortunately a pretty common practice there. I think she was born on the streets to an abandoned mutt, who mixed with another mutt. And she carried on the tradition. Probably good to shake-up all those centuries of inbreeding.

But yeah, I agree, more people should try the Jindo/Chow/Chin mix. She gets a lot of attention from passersby when we walk her.

OMG, if I had a pet named Basil, I’d be calling it’s name like Prunella Scales in Fawlty Towers. I’m laughing just at the thought.

Anyhoo, I was gonna say how our late male Bulldog had bladder stones that required emergency surgery, where the vet literally had to redo his piping with a differnt outlet. So for about 8 months after, dude was squatting to pee. Then over time, I noticed him lifting his leg again when I’d take him for walks. As in, the piping reverted back to its original state. Vet said it does happen, but only about 5% of the time.

I was like , dude, I know you feel you have to live up to your stubborn reputation, but that’s extreme, dog. 😆

I used to pet-sit Basil every Sunday. No response to her name. Basil is smart. The non-response was a mystery. So last Friday, I finally got my answer. The third figure in the original “cappiethedog” avatar was visiting from North Bend. He was staying with the second figure from the original “cappiethedog” avatar. The husband, my friend, the second figure, was calling her Basil with a long ‘a’, and his wife and two sons went with the short ‘a’ version.

Oh, I don’t think my friend is that literary. Her sister is named Olive. The dialogue about Toni Basil is true. I’m being constantly reminded that I sound like a podcast.

The surgery you’re describing for your late great bulldog sounds complex. I’m not sure if there is anybody local who knows how to do that.

I’m a great believer in dogs as being hairy human beings, like the aliens in Earth Girls Are Easy. So I don’t think it’s necessarily anthropomorphism; he knew how it looked to the other dogs on the block. He wanted to feel like a dude again.

Just remember if you’re around German Shepherds, don’t mention the war.

That totally got a hearty hoot out of me, brilliant. 🤣

Oh, look another Mahler recommendation. (I say that sorta nicely and sorta tongue in cheek). My first exposure was in our high school concert band which played exerpts from a Mahler symphony (I don’t remember which one). It was guest conducted by a local university’s conductor. He was over-the-top passionate about Mahler and seemed funny to us how emotional he was about the composer. Over the years I’ve heard so many claims to his being the best ever. I’ve listened to several of his symphonies over the years (including live), but I must confess that I just haven’t ‘gotten’ him yet. Maybe if I live long enough he will eventually click with me.

I definitely think that it’s me and not him. Enjoyed the read, Phylum. 🙂

Well, his style is not for everyone. It took me a while to get him, and I love dark and difficult music.

Here’s one piece that you might like, though it’s often considered uncharacteristic of his work. It’s actually kind of light!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bgmmx6z2TCs

“Mass culture provided cheap and easy entertainment to distract people from their problems, but not to help them grow or heal”

Goodness, this could probably describe every culture/society/empire/country/civilization that ever existed since the dawn of time, right?! You’ll always have the vast majority of folks who are content to just exist and have no qualms about complaining while never actively doing anything to change the source of the complaints…..

And then there’s the tiny percentage of folks each generation determined to do their part to truly make the world a better place. And because of them, mankind somehow continues to find its footing and keep stumbling forward. Those are the true artists. Inventors are artists. Skilled politicians are artists. Teachers are artists. Good parents are artists. Thank goodness for these unselfish folks, stubbornly trying to advance society and help others in the best way they know how.

It’s true, the idea that the masses can be contained with bread and circuses (ie., basic satiety and distractions) goes all the way back to ancient Rome.

But technology often makes everything crazier. Aside from inspiring countless revolutions and sectarian factions, the printing press enabled the rise of local and then national-level press, offering the masses a daily circus of inane stories and ideas.

Things would get even crazier with the advent of radio broadcasting, though Nietzsche himself was not alive to witness that development. Therefore, enter a new prophet/scold: Theodor Adorno.

Ooh, there’s another fascinating topic for discussion – has technology improved society, or does it just make things worse?

It’s like the argument most scientists have over the years – they have honest and supposedly the best of intentions when researching and making new discoveries, only to have some schmuck then steal it and weaponize it.

Yeah, technology grants new opportunities for life improvements, but there are usually hidden costs or other ramifications. So it’s both, but in practice it’s usually not so easy to see the costs, at least until time grants us some hindsight. The general topic is something that I do wish to touch on in this series, so let the discussions commence!

On scientific research, I definitely feel that. I never pioneered something that would require a patent or anything, but I did contribute to the general study of individual differences in brain activity patterns. Now I hear that certain nations are trying to use remote devices to scan people’s brain activity without their consent as information for legal or commercial reasons. A horrifying thought. Not least because the “information” they’re getting is not as reliable as they probably would assume it is, such as for lie detection.

If you build it, they will come…and use it for their gain…