“This orchestra grows rambunctious, rears on its hind legs and attacks the tonal veil with primitive fury, rending it, clawing it until it breaks through to the jungle beyond.

I follow those heathen–follow them exultingly. I dance wildly inside myself;

I yell within, I whoop; I shake my assegai above my head, I hurl it true to the mark yeeeeooww!

I am in the jungle and living in the jungle way. My face is painted red and yellow and my body is painted blue.

My pulse is throbbing like a war drum. I want to slaughter something–give pain, give death to what, I do not know.

But the piece ends. The men of the orchestra wipe their lips and rest their fingers.

I creep back slowly to the veneer we call civilization with the last tone and find the white friend sitting motionless in his seat, smoking calmly.

“Good music they have here,” he remarks, drumming the table with his fingertips.”

Zora Neale Hurston, How It Feels to Be Colored Me, 1928

The artistic Rubicon Crossing for jazz music occurred in Manhattan, New York on February 12, 1924.

Bandleader Paul Whiteman, dubbed by the press “the King of Jazz,” held a concert called “An Experiment in Modern Music,” where he debuted the radically unique composition “Rhapsody in Blue” by a young George Gershwin.

Just kidding. As important as Gershwin was for the world’s embrace of jazz, his work was modern classical, albeit with respectful nods to jazz and blues.

The real Rubicon Crossing for jazz music occurred in Manhattan, New York on September 13, 1924.

This was when a hot young trumpet player arrived from Chicago to join the band of the esteemed Fletcher Henderson, who had recently scored a gig playing for white audiences in Times Square’s Roseland ballroom.

In most respects, this arrival was a non-event. When band members Don Redman and Kaiser Marshall came to pick up the newcomer from the train station, Redman observed: “He was big and fat, and wore high top shoes with hooks in them.

“When I got a load of that, I said to myself, ‘Who in the hell is this guy?’

“It can’t be Louis Armstrong.”

Armstrong had been raised in deep poverty in the slums of New Orleans, a place that may as well have been a Kentucky farm to Fletcher Henderson’s band. This big Southern hick stuck out like a sore thumb in the elegant Manhattan entertainment scene. And maybe for that reason Louis only remained in New York for a year before heading back to Chicago.

Regardless of all that, Louis Armstrong’s playing hit the city like a bomb, and the jazz scene was never the same again.

Armstrong introduced the “hot” style of New Orleans jazz to the New York crowd, who were more known for a “sweet” and elegant style.

He introduced them to the blues.

Not blues tunes per se, but the raw blues style that had formed in the rural South. He blew his horn with more passion than anyone had ever heard.

His sense of melody was remarkable: economical, yet clear and bright, even when improvising. His sense of rhythm was just as impressive, lending the songs what Fletcher Henderson came to call his “New Orleans punch and bounce.” Or what jazz musicians everywhere would later call “swing.”

Armstrong was a sensation at every concert he played.

And soon, every jazz musician in New York wanted to play like he did.

In order to play with Henderson’s band, the young trumpeter had broken away from his mentor, Joe “King” Oliver, another transplant from New Orleans, who headed the hottest jazz ensemble in Chicago.

Oliver was a talented trumpeter who was known for playing with guttural effects that made his trumpet sound like a singer getting wild and bawdy with the blues.

But even he had known that young Armstrong was a better player than he was. He told his pianist as much, and admitted that part of why he kept Louis in his band was to prevent him from rising higher than himself.

But Oliver’s pianist happened to be the woman who would soon marry Armstrong, and Lil Hardin urged her husband to leave Joe Oliver’s band, to go out on his own and take his talent as far as he could.

So he did.

Armstrong grew to be one of the first great jazz soloists in the history of the style. When he played with Oliver, he was given opportunities to solo, but only as brief moments in a larger ensemble piece. Oliver’s approach as a leader was perhaps the pinnacle of the older jazz style, with each player given more or less the same presence, all of them components of the collective effort.

In fact, when Oliver’s band recorded some of their cuts to vinyl, he instructed Armstrong to play 15 feet from the rest of the band, in order to keep the young trumpeter from playing over everyone else on the record.

Yet even in Fletcher Henderson’s band, Louis felt like he was being sidelined, held back from his potential.

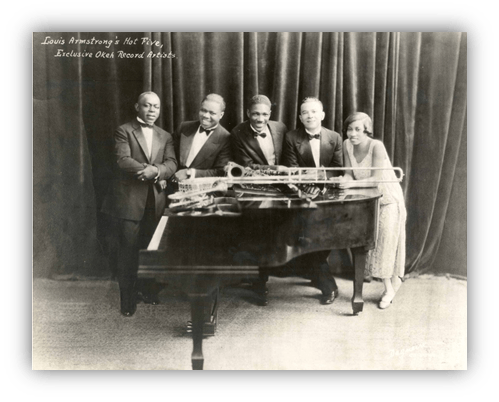

So once he got back to Chicago, he formed his own band: The Hot Five.

On these Hot Five recordings, it’s sometimes hard to hear the other players, as Louis’ trumpet just bulldozes over everything in a nearby frequency range.

The older ensemble approach to jazz was great for its collective jubilation, but in all honesty I find it hard to listen to. It sounds crowded and muddled. Part of that is due to the poor recording quality of the old records, but a lot of it was due to the traditional egalitarian approach to playing. Louis’ executive decision to embody the leader in his recordings gives the songs a lot more breathing room, so that you can start to appreciate what’s going on. Also thanks to Louis, what was going on was a whole lot more creative, relatable, and exciting than what came before.

Armstrong was a major catalyst for the artistic growth of jazz in the 1920s, but he didn’t do it alone.

For instance, New Orleans clarinet and trumpet legend Sydney Bechet had learned a lot from Louis, but he was also regarded as Louis’ toughest competition in soloing, and soon he was giving other jazz musicians advice on how to play.

Fletcher Henderson’s band dedicated themselves to playing the hottest music that New York had ever heard.

Their arranger Don Redman put much more focus on instrumental solos to let individual personalities have their time to shine. One such personality was tenor saxophonist Coleman Hawkins, who became one of the great jazz pioneers of his instrument.

Despite their change in style, Henderson and Redman never lost their sophistication in musical arrangement, and their innovative compositions came to serve as the blueprint for big band swing music, which would become a national phenomenon in the years to come.

There was also Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington, a transplant from a well-to-do neighborhood in Washington D.C. who came to New York in search of a bold new sound that was not found in his formal music lessons.

Like Henderson, Ellington was thunderstruck by the playing of Louis Armstrong (he famously said to his band members that he wanted Louis playing on every instrument), and he also married that hot New Orleans style to a more sweet, elegant and sophisticated sound.

Whereas older jazz was always upbeat, Ellington’s jazz could also be sad, soulful, sinister, sexy—sometimes in the same track!

And Louis himself would continue to expand and refine his sound, such as with his rendition of “West End Blues” in which he and pianist Earl Hines create a dreamy little slice of heaven.

By the late 20s, this dance craze from Dixieland had been completely transformed into something far more dynamic, emotionally complex, dignified, and inspiring than most people could have ever imagined.

Jazz continued to be entertainment music for nightclubs, but it would do so more and more according to the terms of the artist.

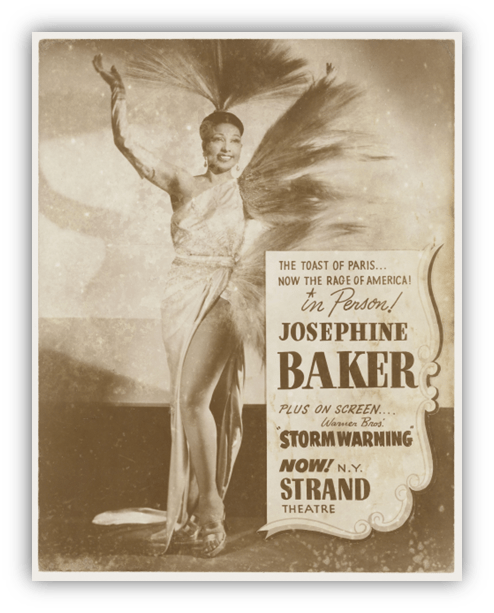

That’s not to say that there were no indignities to endure, of course. The artists and scholars of the Harlem Renaissance who looked down upon jazz and blues simply had to point to the many jazz cabaret shows that featured women dressed in makeshift African costumes dancing wildly to what was supposed to represent primitive tribal culture.

The singer Josephine Baker is the artist most known for these demeaning shows, but she was by no means the only one.

Even Duke Ellington, that conscious purveyor of black dignity, played with his band alongside exotic dancers in banana dresses and tribal paint, and his own work was labeled as “jungle music.” Clearly there was still a lot of progress yet to be made.

And yet, what better way is there to capture hearts and minds than to win them over with something seemingly innocuous, and fun?

To be sure, there were plenty of racist tropes still in effect during the jazz crazes of the 20s. But there was one crucial difference that set this entertainment scene apart from the minstrel shows of old. Namely, the white audiences who came to the clubs and enjoyed the music became active participants in the cultural moment.

Some of them simply drummed their fingers, but plenty more learned black dances such as the Foxtrot, the Charlestown, and the Black Bottom, and they shook their white bottoms til the sun came up.

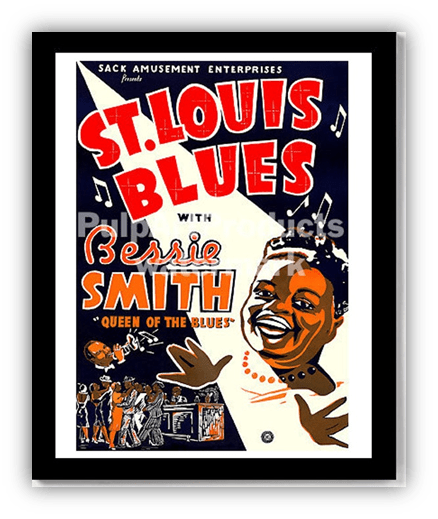

Perhaps more importantly, they were awed by the presence of a talented soloist like Sydney Bechet, or the raw emotion of a singer like Bessie Smith. Jazz in this age wasn’t simply entertaining. It was utterly impressive, it was the epitome of hip.

And sure enough, some white fans of jazz tried their own hands at the music. A lot of early white jazz was enjoyable, but not particularly impressive compared to the best of the black bands. The mid and late 20s saw a few ultra-talented white jazz players come to the fore and actually start to inspire black musicians.

At the head of the pack were Bix Beiderbecke and Frankie Trumbauer, both of whom played for a time in Paul Whiteman’s band in Manhattan.

Their softer, lyrical solo styles would influence countless musicians to come, including the later pioneers of “cool jazz.” Beiderbecke in particular brought in influences from classical, such as Debussy and Satie, further opening up the harmonic possibilities of what jazz could sound like.

Paul Whiteman himself gets little love from jazz fans these days, as he’s commonly regarded as the Pat Boone of his era. The comparison makes some sense, in that he did play a safer and more conservative variation of jazz sounds for wealthy white audiences.

Still, he was a huge proponent of black jazz musicians.

He wasn’t a jazz musician proper, but he was a composer who wished to blur the lines between white and black styles. In that, he was much like George Gershwin, whose work Whiteman also helped to promote.

He also debuted a more avant garde jazz fusion piece by George Antheil, which was performed by the early legend of jazz and blues, W.C. Handy.

No matter what the white press said, Whiteman wasn’t the king of jazz, and neither was Gershwin. Still, they contributed to a broader cultural climate that allowed white fans across the nation to accept this predominantly black style of music, this weird and exciting new musical modernism, as America’s music.

And in the process, white fans began to accept the idea that black musicians like Louis Armstrong or Duke Ellington could in fact be regarded as geniuses, as icons, as heroes to look up to.

Younger artists of the Harlem Renaissance, such as Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston, did enthusiastically embrace jazz music as a vital part of their movement.

So maybe part of the resistance was merely generational. But part of the misunderstanding was the rapid evolution of jazz itself during this time.

This was its own Renaissance of sorts. What started as a collective effort to entertain became the central medium for individualistic self-expression and creative experimentation in music. This revolution did in fact come from the bottom up. And as a result, black communities found themselves armed with some powerful cultural programming tools with which to fight for the soul of the nation.

Dr. Dubois, you’re very welcome.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

This is excellent, Phylum. We can’t overstate Armstrong’s importance to, well, everything that came after him. He’s a towering figure in music and civil rights.

And once again, I’m covering a very similar topic on upcoming Fridays. This could start a conspiracy theory that we’re the same person.

Hmm.

Batman and Bruce Wayne.

Superman and Clark Kent.

The two Darrens from Bewitched.

I’m just saying.

I’d express surprise, but somehow I’ve known all along…

That quote from Zora Neale Hurston that you open with is outstanding. So vivid, life affirming and then the pay off of the contrast with their white friend moved only so far as to drum his fingers.

Thanks as ever for the insight. It scrambles my brain to think this was all 100 year ago. Its so distant but at the same time thanks to being there at the onset of film and recording along with the longevity of the likes of Louis and Duke they almost feel part of the modern world. We’ve come a long way in a short time.

Speaking as someone with plenty of Irish guilt and inhibition, my spirit leaps into that eternal shamanic dance just like Zora does, regardless of what my body might be doing or not doing. Of course, with a little hooch, those inhibitions just melt away…

The early hours, around 6AM, without fail, an AM radio station would play an audio excerpt of Good Morning, Vietnam, followed by “What a Wonderful World”. Oh, wait. No wonder. The song charted. That’s amazing. It reached #32. I thought the radio station was being creative.

I miss Robin Williams.

I still think to myself, what a wonderful song.

But yeah, if the DJs wanted to shake things up, maybe they could have played Satch’s musical tribute to smokin’ doobies:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qY6Yo6lE-Jg

Phylum, I’m really enjoying these early jazz articles. There’s a lot to learn and keep organized in my head. And even though I love a lot of this old music, I never consider myself an expert at it. Good stuff!

Thanks!

I’m by no means an expert either. Most of what I’ve learned beyond the original works comes from academic articles, The History of Jazz by Ted Giola, The Rest Is Noise by Alex Ross, and of course, Ken Burns’ Jazz series.