After World War I, the cities of the US found themselves at a new peak of consumerism and escapist decadence.

This was the Roaring Twenties.

While the Temperance movement advocates had successfully lobbied for a federal prohibition on alcohol, this ban did little to curb the public’s drinking habits.

It may in fact have encouraged more people to drink, in defiance of the law. People with a thirst for booze simply went to speakeasies run by the mafia, instead of establishment saloons or bars.

Women drank in public more than ever during this time, as they previously had not been allowed in many drinking establishments.

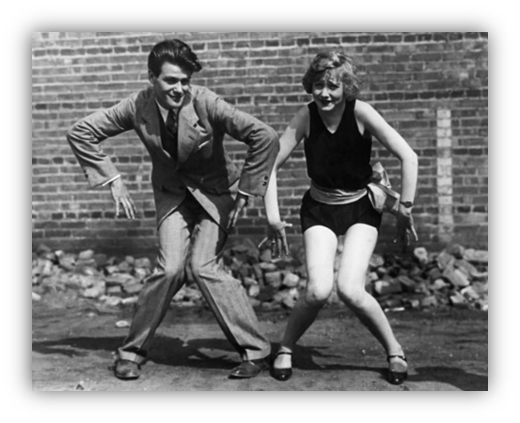

This was the time of the flappers, with their stylish new bobs and their open embrace of sexuality.

In New York City, it was the advent of dance crazes like the Fox Trot, the Lindy Hop, and the Charleston.

It was also a time of major artistic fruition among black communities.

In the 1920s, there was no more significant cultural capital for black Americans than New York City.

Particularly the neighborhood of Harlem in Manhattan.

In the early and mid 1900s, once southern states started to adopt Jim Crow laws to reverse rights that blacks had been granted after the Civil War, there was a mass exodus of black families out of the South, in search of a better life. Northern cities were common destinations, with the most popular being New York City and Chicago.

In the northern part of Manhattan, the historic Harlem neighborhood had flowered into a prosperous community.

Even more, it was a major center of black political, intellectual, and artistic life. Harlem was home to black literary journals that published new works by James Weldon Johnson and Claude McKay, and by promising young talents such as Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston.

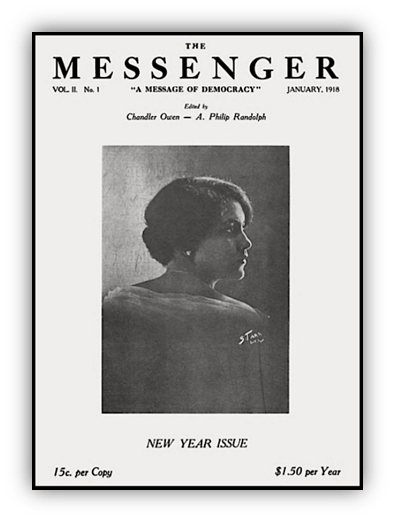

It housed the offices of several black newspapers, such as The Messenger and The New Amsterdam News, who commented on political and artistic events of the day.

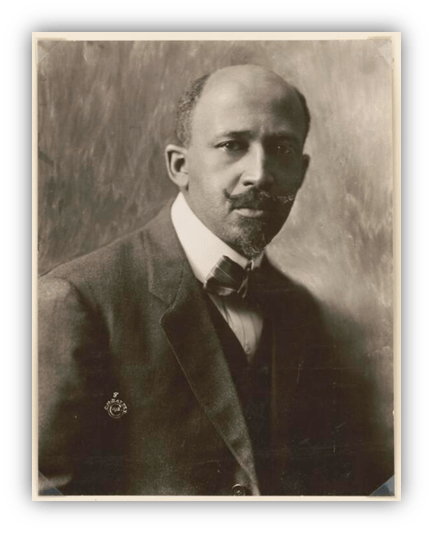

Harlem was the original home of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, or NAACP, a civil rights advocacy group founded by the cultural titan W.E.B. Dubois.

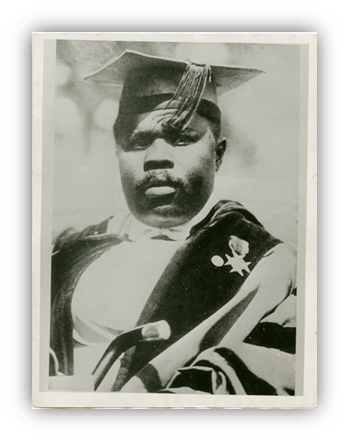

Harlem was also home to Marcus Garvey, who championed a separatist stance for black Americans to counter Dubois’ integrationist efforts with the NAACP.

In short, Harlem was the center of what we now call the Harlem Renaissance.

Though back then it was referred to as “the New Negro Movement.” It was a movement dedicated to help black Americans find their own sense of self worth.

To display their dignity to the rest of the nation, and to claim their rights as citizens without cowering in fear from the threats that surrounded them.

So, what about the music of the Harlem Renaissance?

What was this community listening to at this time in history…which, you know, was also dubbed by F. Scott Fitzgerald as “the Jazz Age?”

Well, jazz. Kind of.

I guess.

It’s a bit complicated, though. I’ll explain. But first, let me go back a bit:

In the final decades of the 19th century, several black American musical traditions were forming, mixing, and evolving together.

One was the jubilant music of the cakewalk competitions from slave plantations, later called “ragtime” after its syncopated, or ragged time. This had originally been inspired by marching band music, but was mainly made for piano.

After the Civil War, ragtime music spread across the country via blackface minstrel shows. Then, thanks to the advent of radio broadcasting, it eventually became a global sensation.

There was also the development of songs with specific 12-bar chord progressions that were labeled as “blues” numbers. Some of these were rollicking marches or lively dance numbers, but a growing number of blues tunes from the rural South began to conjure a feeling of melancholy.

By the late 1910s, several black minstrel show performers had shifted to cabaret performances.

They spread this passionate rural variant of the blues across the cities.

Some such piano blues tunes were on the bawdy side, but they nevertheless also gave voice to the raw feeling, pain, and heartbreak that we all now associated with someone “playing the blues.”

And then, there was “jazz.”

A musical gumbo of various black styles that first simmered together in New Orleans.

Jazz bands descended from marching bands, but also included banjos and piano. Other than the steady, stomping four-four rhythm, the musicians played in ragged time, and they often played blues progressions.

Yet most of the early jazz was bright and jaunty dance music, like ragtime, except louder and more freewheeling, with its many instruments contributing to a cacophonous rush of joy.

Sometimes the players would chime in with improvised melodies for added excitement. Sometimes they’d throw in Afro-Cuban rhythms and stop-start dynamics for extra flavor. There was no one recipe for jazz. What was most important was the collective effort of the players in the band to make the liveliest party music anyone had ever heard.

Thanks to jazz bands being booked to play on riverboats and on trains, the hot new music of black New Orleans spread to the major cities in the 1910s.

It also spread as blacks migrated North to escape the stranglehold of Jim Crow, as previously mentioned.

By the time of the 1920s, musicians from New Orleans could find easy work in Chicago or New York City, playing in one or more of the countless speakeasies that had popped up in the wake of Prohibition. The players thus began to develop their own variations of the style that suited each locality.

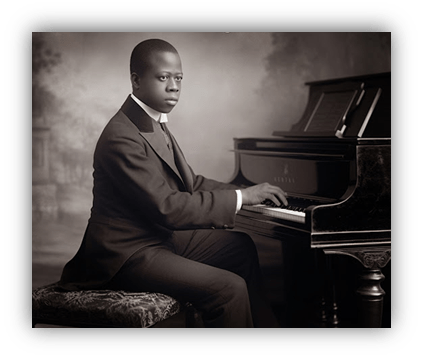

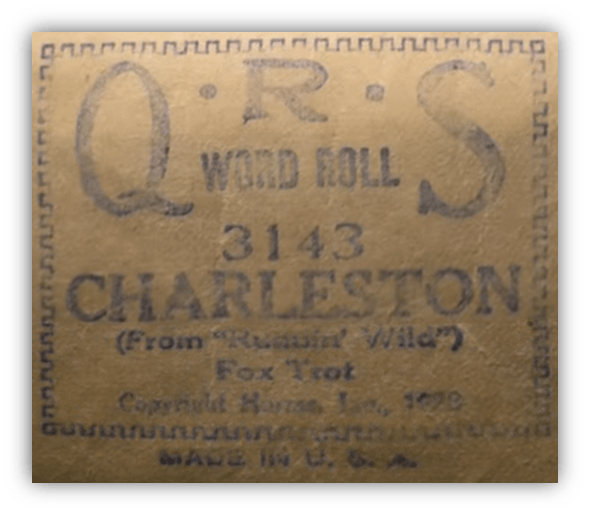

The sound that dominated Harlem in the early 1920s was the stride piano style. The father of stride piano was James P. Johnson, and his 1923 tune “The Charleston” also happened to kick-start the dance craze of that same name.

It was fun novelty music, sure, rooted in ragtime piano music. But the top stride players were formidable talents, having to stand out in a city known far and wide for its classical musical elite. They honed their skills together via “cutting” contests to determine who was best.

Stride legends like Johnson, Willie “the Lion” Smith, and Fats Waller were able to take dance tunes to dizzying new heights of musical virtuosity and showmanship with which to captivate their audiences.

However impressive their playing may have been, some audiences could not be swayed. This unfortunately included many pioneers of the Harlem Renaissance, who felt that ragtime, stride, blues, and jazz music were an embarrassment for black America.

These folk novelty tunes and dance fads were leftover echoes from the minstrel shows. They were not a music befitting the dignity of the New Negro.

Quoth a black journalist on the growing jazz craze:

“Jazz is a razz of aborted syncopation and instrumentation.”

“It is probably here to stay, in order to appease the exotic period which recreation seems to demand nowadays.

It is the “chop-suey” of the musical world – but the world seems to want more and more of it, sad though that fact be;

and it is a blessing that Schumann, Mozart and Mendelssohn are not present to hear it,

for they would think, indeed, that they had lived in vain.”

New Amsterdam News, October, 1926

To us, this sounds like standard class snobbery. And that certainly was a factor in black distaste for the entertainment styles of the time. Harlem was, after all, home to a large concentration of black wealth in America—and class contempt is one thing that unites all races, unfortunately.

But it’s more complicated than that. Following the re-emergence of the Ku Klux Klan in the mid-1910s, anti-black violence once again began to increase across the nation.

The NAACP had fought to censor D.W. Griffith’s klan-worshipping film Birth of Nation due to its role as dangerous propaganda.

They were unsuccessful, and the film did indeed incite anti-black violence.

While figures such as Marcus Garvey saw such violence as more evidence that blacks needed to separate themselves permanently from white society, integrationist leaders like W.E.B. Dubois longed to counteract such hate mongering with their own cultural counter-programming;

with art that could move hearts and minds to the humanity of black people, and to the common humanity of us all.

“Thus all Art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists.

I stand in utter shamelessness and say that whatever art I have for writing has been used always for propaganda for gaining the right of black folk to love and enjoy.

I do not care a damn for any art that is not used for propaganda.

But I do care when propaganda is confined to one side while the other is stripped and silent.”

The Crisis, October, 1926

Dubois was born shortly after the end of the Civil War, and in 1895 he became the first black man to get a PhD from Harvard University.

He dreamed of new musical movements inspired by African American traditions such as spirituals.

But like Antonin Dvorak, Dubois’ dream took place in the elite sphere of composition in the European classical tradition. He could not fathom how his dream of black dignity and common humanity could possibly come from the entertainment world, where musicians shamelessly pandered to their patrons for a few extra bucks.

The revolution of the New Negro simply could not come from below.

…Or couldn’t it?

(To be continued…)

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Great job as always, with a good hook for the next installment…

I see you and V-Dog moving like mostly parallel lines that are sometimes wavy and intersecting… I’m sure our artistically inclined editor could come up with a Venn diagram or other interpretation.

Thanks! Yeah, it’s not pre-planned, but it weaves together nicely.

🎶🎵🎶

It’s a nice coincidence, isn’t it? I’m currently writing about this period (for publication some weeks away) and it dovetails nicely into what you’ve got here.

“Thus all Art is propaganda” is a great quote. I’ll have to remember that one. Nice job, Phylum!

Yeah, and I know what he means…as long as we’re talking about changing people’s hearts and minds to have more compassion, and advocating for a cause.

My previous post was about propaganda, but for me that one’s the less savory variety. Appealing to emotion and identity are obviously important for persuasion, but throwing away all notions of reasoning to rig market demand and to exacerbate popular fears feels much more cynical. It’s persuasion without any recognition of the audience’s own autonomy and dignity, i.e. manipulation.

What definition of propaganda did Dubois have in mind? I can’t say for sure. I lean toward the former. But he was a complicated figure, so it’s possible he had a more shrewd and severe vision than I infer.

More about this in part two!

Thanks Phylum, this is awesome! I have always had a soft spot for the Harlem Renaissance. Claude McKay, Nella Larsen, Jean Toomer, and of course Langston Hughes and Zora Neale Hurston. Their literature helped me to peel back the onion and start to fathom the inner lives of black people of that era. How would you see a white woman after people you knew were lynched? How would you understand what it means to be black if you immigrated to the US from another country? If you could pass as white, would you do so, gaining significant advantages in life while feeling like a traitor?

Point being, the history books only frame being black in Jim Crow era as an unmitigated tragedy. Which it certainly was. But the people are not solely defined by their victimhood. The writers of this era helped me see them not as victims but as people, who are behaving more or less exactly as I would or as you would given the same circumstances. Plus it all stands on its own as excellent literature… it’s not just a empathy lesson, or that would be boring.

I love me some Zora Neale Hurston. Researching this topic has made me a little more familiar with writers beyond her and Langston Hughes, but more than anything it pointed out just how much there is for me to dig into!

Any recommended works?

Jean Toomer’s Cane is a great collection of vignettes — some sort fiction and poems. Nella Larsen’s Passing was recently made into a Netflix movie starring Ruth Negga — I preferred the book to the movie. Claude McKay can be difficult because he uses a lot of vernacular, but I liked Home to Harlem.

I am currently reading Bob Stanley’s, Let’s Do It, which chronicles pre-Rock’n’Roll from roughly around early 1900s. It is fascinating and this piece nicely compliments it. Well done, and I need to go back to read previous your previous columns. A plug for the Stanley book which is also filled with astute observations and a good deal of humour. It has also given me an even bigger appreciation for Louis Armstrong, who was so influential, and does not get his proper due. Perhaps he was in a previous column?

Next one!

I just ordered “Let’s Do It.” Thanks, R.S.!

A very talented man is Bob. Very accessible writing, filled in a lot gaps in my knowledge and fits a lot in without feeling like he’s rushing through it all. Let’s Do It and Yeah Yeah Yeah do a fine job of covering the entirety of popular music through the 20th century.

I previously read Yeah Yeah Yeah and was amazed at how anyone could cover so much and make the lot so informative and entertaining. I am less familiar with the music covered in Roll, so it is a different type of read. The humor is more prevalent in Roll and there are numerous audible laughs as I read each chapter. I especially like how he compares/contrasts what was happening in the UK and US. Between the books, the articles, the band, and the assembly line of Ace compilations, I don’t know how he does it. And then there is also the computer database of hundreds of thousands of songs in his brain. Possibly, a music loving, human/AI hybrid? Blessed to live in the same world.

I didn’t know about the Ace Records compilations. Thanks for switching me on to them. Just been having a look and just the artwork and album titles are fascinating aesthetically. Looks like lots of deep cuts within the compilations, lots to dig into.

#JusticeForChopSuey

The term chop suey is a lot older than I thought. I watched The Flower Drum Song in a classroom. The song “Chop Suey” isn’t the stuff of earworm, but I can’t unhear it. Chop suey: Chinese food or fake Chinese food? There doesn’t seem to be a consensus online. Chop suey is slang here for a person who has too many ethnic heritages to count on one hand.

I read There Eyes Were Watching God as an assigned book during my senior year in high school. It was a simpler time. Our only objection was that we had to read any book.

There used to be an African-American section for fiction at Borders. I wonder when that practice stopped?

The Trees showed up on the NYT Notable Books list in 2022. I thought Percival Everett was a new novelist. I never heard of him. As it turns out, Everett’s been publishing since 1983.

I’m looking at Zora Neale Hurston’s Wikipedia page right now. Seraph of the Suwanee interests me. It ended her career. I bet it’s more interesting than her more celebrated works.

I wonder (with not much insight other than noting some of the noise surrounding the topic from both sides) how much this stratified response to jazz is similar to the continuing discussion of hip-hop.

And are we going to through this with every new artistic direction emerging from downtrodden and disenfranchised groups?

As always, great grist for thought, PoA.

Thanks!

Yeah, probably, to some extent. If something is new and it’s from “not us,” it must be defective in some way, rather than simply different.

Part of it might also be generational. Certainly for Dubois.

There’s one more reason that I will go into next entry, and it seems fairly relevant for hip hop as well.

Ah the Lindy Hop. More energetic than I generally liked even in my youth.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qkthxBsIeGQ&t=1s

Wow, I’m exhausted just watching it. That is being played at the right speed?!

The original breakdancing! Not just via the broken limbs that my brain jumps to when I see some of those moves, but some of the actual moves look like precursors. Particularly the one where the woman does that crab walk across the floor.