“The interpretation of dreams is the royal road to a knowledge of the unconscious activities of the mind.”

Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams

Of all the avant garde movements of art history, Surrealism is one of the most popularly known, even now. It’s known even by people who know nothing about art.

Melting clocks.

Guy with an apple for a face.

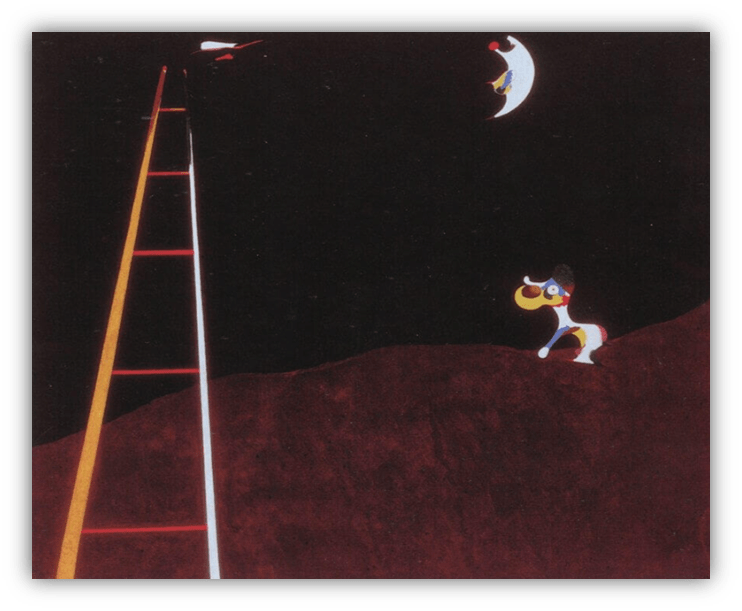

A dog under a moon, and the dog kind of looks like an amoeba. You know the one:

What was the deal with the Surrealists?

Just a bunch of weirdos trying to stand out with some outlandish imagery?

One too many hits from the bong? Or is there something more potent underneath the surface?

Let’s investigate…

The term “surrealism” was coined by poet Guillaume Apollinaire around 1917 to describe the aspirations of his modernist compatriots such as Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau, and Erik Satie.

Their works and his own were radical new artistic expressions of a transcendent reality that “kept pace with scientific and industrial progress.” After World War I, several groups of artists followed Apollinaire’s lead to pursue this notion of Surrealist art.

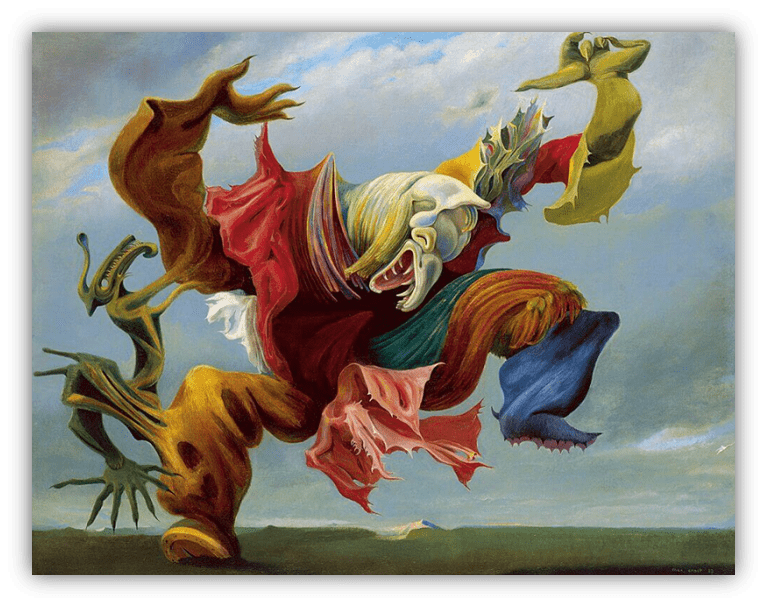

Most prominent among those groups were the artists that had unleashed Dadaism upon the art world. After raging against rationalism through performative nonsense, Dada artists such as Andre Breton, Andre Masson, and Max Ernst began to devote themselves more seriously to the idea of exploring the unconscious mind through their art.

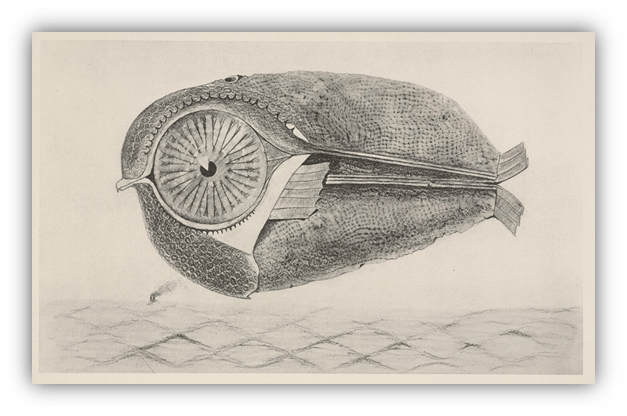

The poets would engage in “automatic writing,” putting to paper whatever came to their minds without reworking or censoring. Man Ray contributed striking images via experimental photography. Max Ernst refined his approach to photo collage to make some oddly arresting scenes.

He also pioneered the technique of “frottage” (rubbing of a pencil against variously textured surfaces) to yield uncanny shapes and creatures, as if pulled out of a dream.

In his 1924 “Surrealist Manifesto,” Breton gives the term an explicit definition:

The Surrealists believed that if people could awaken the dormant irrational psychic energies that modern life tended to repress, then societies would undergo a cultural revolution that would lead to a more liberated and just world.

If this sounds familiar to you, it’s because you’ve been keeping up with this series!

If you think it also resembles the acid-infused bohemian idealism of the 1960’s hippies, it’s because Surrealism was a huge inspiration for that movement.

Unlike the hippies and earlier avant garde circles, drugs didn’t play a role in Surrealist art.

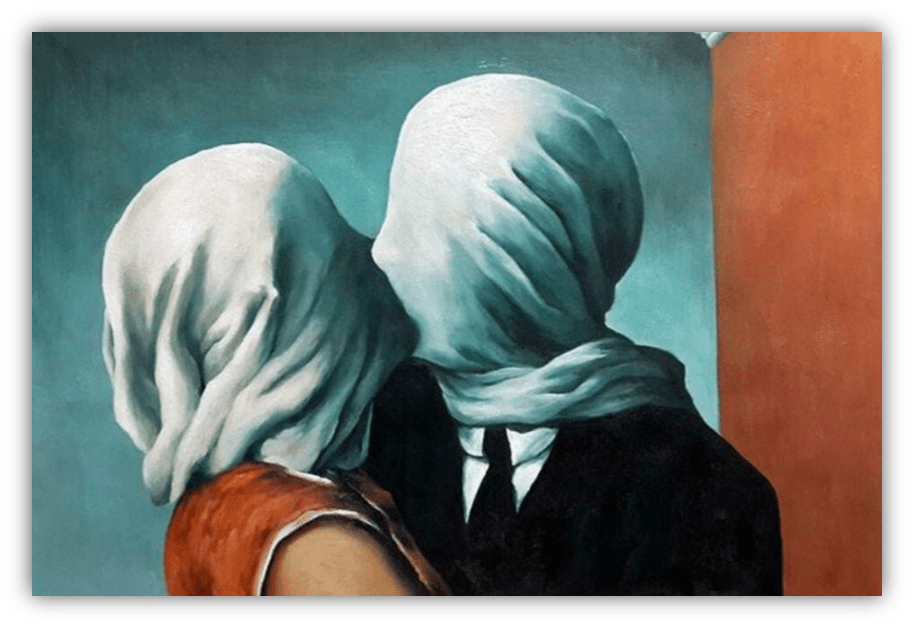

The principal influence for the movement was the scientific writing of Sigmund Freud, the psychologist who introduced the world to the idea of unconscious desires that drive human thought and behavior. The uncanny images evoked by Surrealist painters and poets arose from their attempts to suffuse the ordinary aspects of modern life with the raging lusts, terrors, and contradictory feelings that dwelled in the recesses of their minds.

This was an artistic circle that had some quasi-scientific layers to it. A few of the members even had backgrounds in psychiatry and medicine before pursuing art. Accordingly, the Surrealists met regularly to transcribe their dreams.

They held formal group discussions about sexual desire, an effort that predated the research of Alfred Kinsey by a few decades.

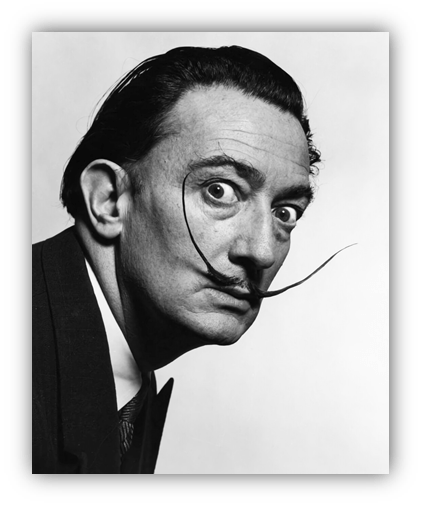

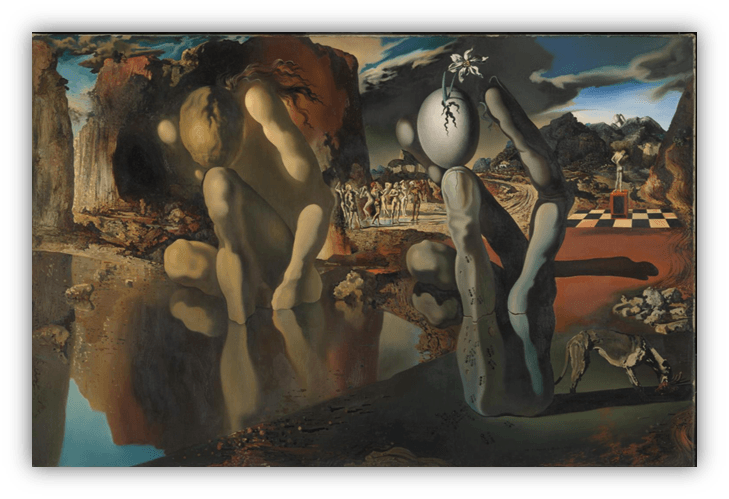

Salvador Dali, who joined Breton’s group in the 1930’s, employed what he called “critical paranoia”–chance misinterpretations of ambiguous scenes or objects–to inspire the beguiling ambiguities and double images that feature prominently in his paintings.

Without realizing it, Dali seemed to wade into waters of visual perception research that the Gestalt psychologists were formalizing around the same time. (Or maybe he was just into M.C. Escher.)

Sigmund Freud, for his part, would not prove a willing father figure to the Surrealist movement. Breton wrote to Freud a few times in the early 30’s, and Freud politely demurred on lending his thoughts on Surrealist works, saying that his expertise lay in science and not in art. After decades of controversy surrounding his ideas, Freud’s pioneering efforts in psychoanalysis had since been accepted by his academic peers, and he likely did not want to risk tarnishing his reputation as a man of science by giving credence to some upstart artistic weirdos.

And yet in 1938, after Dali visited Freud and gave him a copy of his painting The Myth of Narcissus, Freud changed his mind somewhat. He wrote to the man who had arranged the visit:

“I really have reason to thank you for the introduction which brought me yesterday’s visitors.

For until then I was inclined to look upon the surrealists – who have apparently chosen me as their patron saint – as absolute (let us say 95 percent, like alcohol), cranks.

That young Spaniard, however, with his candid and fanatical eyes, and his undeniable technical mastery, has made me reconsider my opinion.”

Sigmund Freud – 1938

Interestingly, Dali himself got the impression that Freud wasn’t interested in engaging with him.

Little did he know that Freud had grown quite deaf at the time, and was not intentionally ignoring him as Dali probed for his thoughts about the painting. So, our young Narcissus did not get the validation he was seeking from his hero. But at least the tragic irony of the meeting adds a touch of mythic drama to our remembrance of his life story, no?

“The virtuous man contents himself with dreaming that which the wicked man does in actual life.”

Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams

Less than a year after his meeting with Surrealist phenom Salvador Dali, Sigmund Freud would flee to England to escape the Nazis, where he would soon succumb to cancer and die. After witnessing Europe descend into war and desolation not once but twice, after the rise of the Nazis and their systematic demonization of Jews, Freud’s take on human nature had grown quite cynical in his later years. He knew the cruelties and atrocities that supposedly civilized men were capable of, and he doubted that human societies would survive these tensions and explosions of animal aggression.

Given everything that was happening around them at the time, how did the Surrealists feel about cruelty and aggression with regard to human nature?

That is a harder question to answer than you might think.

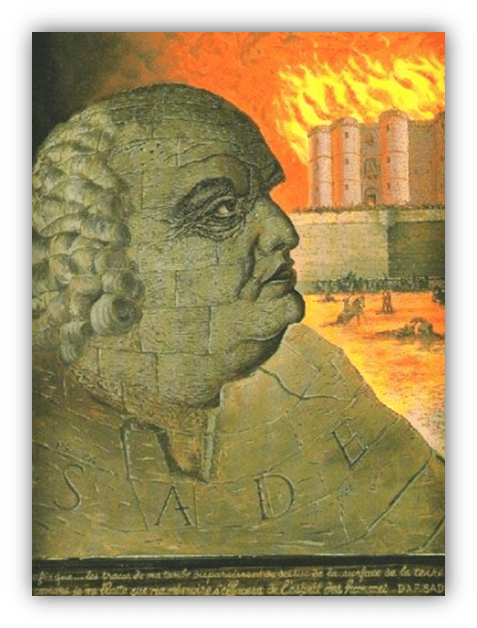

Part of the difficulty lies in the influence of someone who was praised as the other patron saint of the Surrealist movement: the Marquis de Sade.

Yes, the notorious 18th century French nobleman who was arrested and jailed for acts of lewdness and cruelty–from which we now have the term “sadism”–had become a central inspirational figure for bohemian artists around this time. To writers like Apollinaire and Breton, “the Divine Marquis” was the embodiment of Romanticism before the movement had even started. They saw him as an independent thinker who was unfairly imprisoned and later demonized for his eccentric sexual preferences and his revolutionary sensibilities. Indeed, in 1789 Sade shouted from his cell of the Bastille to call the revolutionaries to break in and free the prisoners.

Sade’s written stories, such as Juliette, Philosophy in the Bedroom, and 120 Days of Sodom, were lauded as radical literary works that transgressed conventional notions of morality for the sake of sublimity and artistic emancipation. Georges Bataille even argued, via a brilliant mix of psychoanalysis and sociology, that Sade’s legacy could serve as inspiration for cathartic and purgative practices to keep a society’s fascist impulses in control.

Strange as it might seem for Marxist bohemians to worship a man who took aristocratic privilege to sociopathic extremes, it must be said that the Surrealists never entertain the notion that Sade actually had tortured or raped anyone. In other words, those who worshipped The Divine Marquis focused on the mythic power of his biography and his transgressive written work. Not unlike Freud, they were more interested in the deeper meanings than with the surface explanations. Their treatment of Sade actually resembles how William Blake wrote of Satan in his 1793 work The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: as representing the libidinal will that challenged reason. Thus the Surrealists did not take the allegations of Sade’s cruelty at face value. To them it was a symbol, a banner for their own cultural rebellions.

Now, with regard to more contemporary figures of cruelty, most of the Surrealists passionately denounced Hitler, Nazism, and any form of fascism. They were also prominent opponents to colonialism and the subjugation of other cultures. Most of them pined for communist revolution, but from their historical vantage point, that utopian ideal had not yet been soured by reality. Despite their inflammatory rhetoric, most of them did actually aspire to be humane and considerate people.

Were there exceptions to the rule? What about that eccentric young Spaniard, with his candid and fanatical eyes?

Well, that’s harder to say for sure. Perhaps it depends on how you look at it.

“Human life should not be considered as the proper material for wild experiments.” — Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams

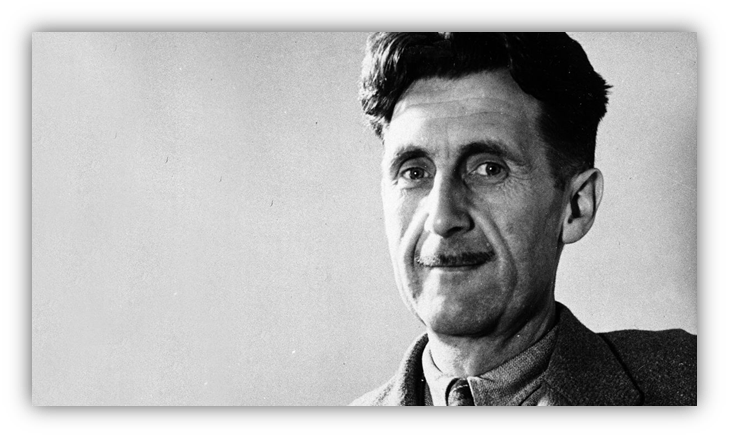

In 1944, George Orwell wrote a scathing review of Dali’s autobiography, “The Secret Life of Salvador Dali.” To be fair, Orwell looked down on Surrealist excess in general.

“If you threw dead donkeys at people, they threw money back,” he jibed. But he considered Dali to be uniquely poisonous.

He cites numerous autobiographical anecdotes involving cruelty to animals and other humans as evidence of his character defect. “Which of them are true and which are imaginary hardly matters, “Orwell writes, “the point is that this is the kind of thing that Dali would have liked to do.” In other words, Orwell thought it important to take the myths of cruelty at face value.

The Surrealists certainly had their own suspicions about Dali.

In 1934, the Spanish painter was put on trial by his colleagues, who accused him of harboring sympathies to Hitler and to fascism more broadly. Their suspicion was motivated at least in part by Dali’s irreverent treatment of leftist hero Vladimir Lenin in his painting The Enigma of William Tell.

That’s a line of thinking that may seem naive from our point of view, but in the 30s the horrors of Soviet communism had not yet been exposed. In any event, the political turmoil of the 1920s through the 40s provided European artists with nearly nonstop opportunities to make it clear where they stood with respect to the rise of fascism.

And yet Dali never really did so. Instead, he ruminated on Hitler as some sort of mythic symbol, painting cryptic tributes to him in The Enigma of Hitler and The Weaning of Furniture-Nutrition (see below).

“I dreamed of Hitler as a woman, “ he later wrote in his autobiography: “His flesh, which I imagined as whiter than white, ravished me. I painted a Hitlerian wet nurse sitting kneeling in a puddle of water.”

Personally, I don’t think that it’s clear that Dali had fascist sympathies. In this particular painting, he seems to draw some connection between his own bourgeois upbringing and the rise of fascism, which could actually be a trenchant critique of both. His anecdotes about young cruelty could have been tasteless fabrications to whip up controversy, an attempt to build a mythos around himself to compete with the Marquis de Sade. Decadent, to be sure, but not necessarily evil. In his defense to Breton’s charges of fascism, Dali pointed out that his own paintings would in fact be burned by Hitler, which was certainly true.

Still, Dali reveled in ambiguity, and it remains possible that shocking comments like “Hitler turned me on in the highest” were more candid than absurd. Ultimately, just as with his films and his paintings, there is no clear interpretation of Dali’s stance that makes itself known to the public.

The Triumph of Surrealism

“The sheer size too, the excessive abundance, scale, and exaggeration of dreams could be an infantile characteristic.

The most ardent wish of children is to grow up and get as big a share of everything as the grown-ups; they are hard to satisfy; do not know the meaning of ‘enough.”

— Sigmund Freud, The Interpretation of Dreams

Admittedly, Dali’s guarded approach to his art often leaves me cold. My favorite work of his is the aforementioned Myth of Narcissus painting, which is at once visually sumptuous, emotionally expressive, and rich in symbols that are not completely obscure.

The Narcissus myth is about vanity and endless self-reflection, with the beautiful youth wasting away as he gazes upon his own image in the waters.

But as with all myths, there are deeper layers of meaning to access. While Dali’s own clues about the work point to a theme of same-sex longing, I also think the painting’s imagery serve to comment on the introspection and self-reflection processes that are central to all Surrealist art.

Reason is a crucial ingredient for human progress, but it’s important to acknowledge that we humans are not perfectly rational creatures. We have feelings and thoughts that we can’t always explain, sometimes we experience a mix of contradictory emotions. While the cultivation of reason was historically important, it’s arguably just as important for humans to give voice to the irrational aspects of our nature.

Max Ernst once described his goal in art as having one eye open, fixed on reality, and having the other eye closed, looking inward.

To me, the best Surrealist art manages to strike that balance between open and closed, between reality and the dream world.

However, this approach has its own peril. There is the risk of veering into confabulation, of wasting away like Narcissus in unchecked self-indulgence. Or, to put it more crudely, of getting stuck inside your own butt.

Sigmund Freud was a trailblazer for the field of psychology, endeavoring to explain puzzling aspects of human nature without much guidance from previous thinkers, yet nowadays Freud’s field of psychoanalysis is dismissed by the scientific community as pseudo-scientific, a province for confabulists and charlatans.

It is true that Freud’s theories were never amenable to scientific testing. Yet it is also true that the scientific method still hasn’t yielded much insight into the rich tapestry of feelings and drives that we humans experience consciously and not-so-consciously. It may simply be that the largely quantitative and disconfirmatory nature of experimental testing is poorly suited to capture the subtleties and detail of subjective mental states.

If that is the case, perhaps philosophical ruminations and evocative art are the closest we will be able to get to capturing our inner dreamworld for others to see, however imperfect those endeavors may be.

The Surrealists represented perhaps the clearest instance yet of the need to challenge the rationalist excesses of modernity. They could certainly be accused of having their heads lodged up their own butts. And they should have tried to reckon with the face value of Sade’s legacy, with the reality of cruelty and power, and how they can readily feed the flames of fascism and tyranny.

Regardless, their best work managed to capture something special about human experience: the intricate dance between the conscious and unconscious, between rational and irrational. And while a lot of the imagery they generated at the time was shocking or at least uncomfortable, such confrontation can be a healthy counterpoint to the culture of easy escapism that modern commercialism tends to generate.

Their cryptic, irrational approach to cultural commentary will never be as politically expedient as the revolutionaries often wish, and maybe some outright monsters will co-opt the approach for evil purposes.

Regardless of the risks involved, it is nevertheless a crucial thing from time to time to wake people up to the reality of their dreams.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Nice job, Phylum! Surrealism, like Jazz, is hard to explain but you did good work here.

Anyone visiting Florida should skip one theme park or another and go to the Dali Museum in St. Pete. The collection is fantastic, literally. I haven’t been there since they opened their new building, which interestingly was designed by Yann Weymouth, brother of Tina Weymouth from Talking Heads.

Also, “Upstart Artistic Weirdos” would be a good band name.

Thanks! I didn’t realize that there was a Dali museum in St. Pete. Pretty appropriate, as Florida definitely has a surreal vibe to it.

Usually if I visit Florida, it’s in the Tampa/Clearwater area, so I should definitely check that out.

Another great article, and I have to say:

Dog Barking at the Moon by Joan Miro is my favorite painting of all-time. It’s usually at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but not on display at this time.

We’re members, and every time we go my kids want to see it… but haven’t been able to yet.

Thanks! I wanted to comment more on Miro’s approach to painting, but this write-up was already pretty big as it is. I will probably include him again in a future article.

I can’t find Miro’s quote about art, but in response to someone who questioned his (I think) Circus Horse, he said something to the effect of, “when I painted it, I saw a circus horse. When someone comes to see it, they can see whatever they want to.”

I used to use the quote when I taught Modern Art.

I was always partial to Dali’s The Temptation of St Anthony…

“…Or: I Deserve a Break, But Does it Have to Be a Fracture?”