As the first world war ravaged the lands of Europe:

As Futurists, Fundamentalists, Fascists, Stalinists, and Surrealists all formed and advanced their radical ideas:

Some folks in America were quietly starting to spearhead their own artistic revolution.

In 1925, the New Music Society was founded by composer Henry Cowell to promote his own works, as well as that of any kindred spirits.

This was a society for the American composers labeled both by their admirers and critics as “the ultra-modernists,” those who embraced the new, and reveled in the unknown.

As a whole, these ultra-modernists tended to be a good deal more modest than their European peers. Perhaps because the cultural foundations for avant garde art were not as strong here. Or perhaps their economic foundations were less certain.

But, modest or no, there’s still plenty of weird and wonderful gems to be had. Let’s have a quick meet-and-greet for some of the members of this group.

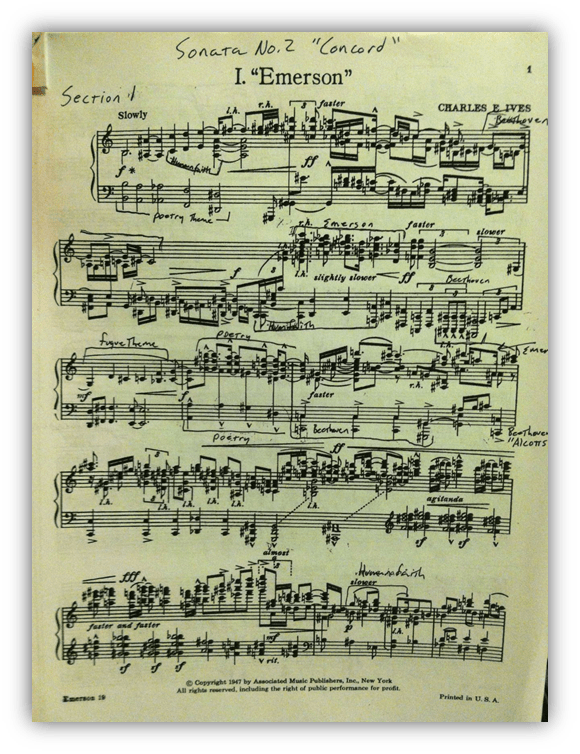

Charles Ives

Charles Ives had been composing since the 1890s, and by the 1920s had largely ceased all composition beyond tweaking some of his older works. Even so, most of his works would not be performed until the 1950s and 60s. In fact, the world probably wouldn’t know him at all if it weren’t for the support of Cowell’s New Music Society. Why is that?

Well, let’s take his New England Holidays symphony as an example.

The “Fourth of July” portion of the piece requires two conductors to lead separate teams of musicians to play separate parts of music, simultaneously. So you basically have two songs played at once, each with their own melodies, rhythms, keys, and tempos. All of it crashing together, like two rival marching bands at a double-booked parade. The resulting earful can be exhilarating to adventurous listeners, but one thing it’s not is accessible!

One signature of Ives’ music is this discordant interplay of separate elements.

Why would he do it? The general notion originated in some of his father’s musical ideas.

His father literally did arrange to have two marching bands pass and play two sets of music simultaneously. One wonders what the family’s nightly meals were like. Or the worship services at the family’s church in Danbury, CT, where young Charles would play organ.

But there’s a deeper reason for it. In his Holidays symphony, as well as in “Central Park in the Dark,” Ives wanted to capture the chaos and energy of a celebration in a public space, which often involves the hustle and bustle of competing sounds. A bit of musical realism if you will, at least for listeners familiar with town or city life:

On the other hand, sometimes he used musical discordance to evoke something more existential. His piece “The Unanswered Question” is quite short, and yet it perfectly conjures a feeling of disconnection, one that finds no resolution. A bit of musical philosophy, if you will.

As ear-piercing as his work can sometimes be, Ives’ work is only rarely dark. In fact, those moments of discordance were only one way that Ives played with irresolution. Another method often shows up in his warmer and friendlier passages, in what resembles a composer’s version of sampling.

Ives loved the folk tunes of his youth. But unlike most composers, he had no desire to adapt or integrate his borrowed melodies into a larger, coherent, symmetrical piece. Instead, he wanted the borrowed bits to remain as they were.

So Ives’ works are full of fragments of well-known songs, stitched together willy nilly, like a patchwork quilt of sound.

He even wrote special notation to preserve all the various idiosyncrasies of down-home folk playing in his grand symphonies.

His works are collages of memories, observations, and feelings–and the various pieces are rarely resolved or assimilated. Barn dances mingle with Brahms, and ragtime gets the same respect as Richard Wagner. The resulting music sometimes sounds like the orchestra is drunkenly humming whatever tune comes to mind. Ives’ work can certainly be warmer than the other modernists of his day, but it is also a good deal weirder.

Not surprisingly, it took quite some time for many in the music world to catch up and appreciate his resolutely unrefined brand of genius.

Henry Cowell

San Franciscan Henry Cowell started writing music in the early 1900s, with his first truly important pieces being written around 1916. Many of his pieces feature simple inviting melodies, but his early seminal works are more famous for introducing strange new tones to musical composition and performance.

The use of discordant passages had been growing more common in modern compositions, but Cowell’s clusters were a giant leap forward.

In 1924, Cowell debuted “The Banshee.” Stop and listen to the track, and try to think what instruments are being used. Emerging from soft tone clusters and a somber piano melody, there are ghostly wails and shrieks that mimic the spirit of the song’s name. Those banshee sounds were created by Cowell opening up a piano, and stroking or striking its strings.

Perhaps you’re inclined to dismiss Cowell’s sonic innovations as mere gimmick:

Or like a child banging away at an instrument rather than the work of a skilled adult.

You’re not completely wrong! Cowell’s early music is undoubtedly imbued with a sense of humor, even mischief. For a certain type of avant gardist, there will always be accusations that they’re not “real” musicians. The artist might even agree, and take it as a compliment. But to focus solely on the conceptual trappings while ignoring the expression through sound is to miss out on their true power.

Then again, if you’re not getting angry reactions, you’re not doing your job as a modernist. When Cowell toured Germany in 1923, his music instigated angry uproars at the concerts in Leipzig, Munich, and Vienna. Job well done, sir.

Still, Cowell’s later work shows that he wasn’t just in it for the edgelord points. Those pieces are a good deal more compositionally complex, yet also with a sense of restraint. He also incorporated musical ideas from Japan and India, a direction that would influence the next generation of avant-gardeists in America.

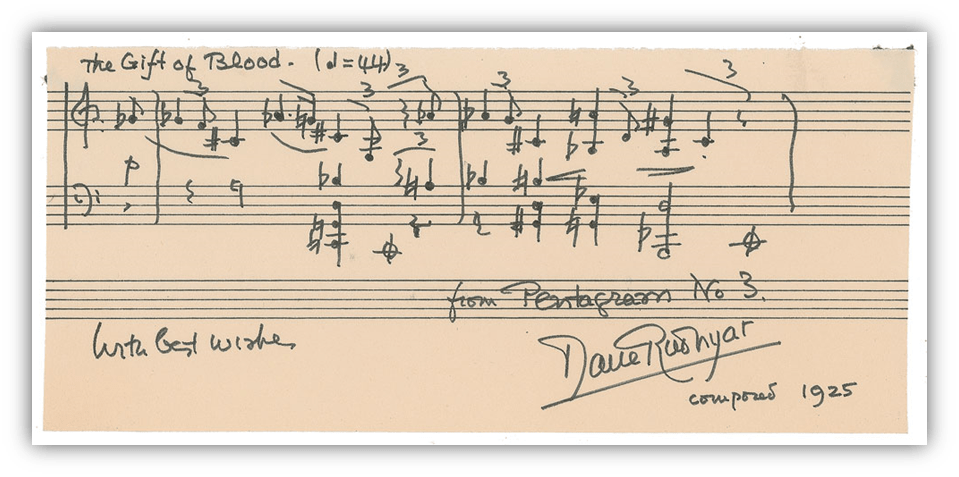

Dane Rudhyar

Speaking of Eastern influences, Dane Rudhyar was thoroughly into the pan-cultural hermetic mysticism of the Theosophical Society, and also Zen Buddhism and whatever else gave good vibes. Born in Paris as Daniel Chenneviere, he later chose to call himself by a Sanskrit name based on the Hindu god Rudra. While living in Montreal, he was turned onto the musical innovations of Russian composer Alexander Scriabin, who himself was dedicated to unlocking theosophical truths with his music. In his own works, Rudhyar came to employ what he called dissonant harmony, or notes that exist in complimentary tension with one another.

The notion made sense to him metaphysically:

“Dissonant music does not solve once for all the problem of unification, does not resolve dissonances into consonances.”

“It propounds problems which the hearer must solve for himself subjectively,”

Dane Rudhyar – 1928

He wrote in 1928: “Music, as well as life spiritually considered, is not something done, to which we have but passively to respond. It is something being done.”

Get to it, people!

As such, listeners may find his works to be a bit on the eerie side.

But there are plenty of softer, meditative passages that are more traditionally pretty:

Rudhyar also helped to develop humanist astrology, an approach that has informed my own system for tarot reading. He continued to pursue both music and astrology into the 70s, and is now considered one of the early proponents of the New Age movement.

Ruth Crawford Seeger

Ruth Crawford studied composition with the ethnomusicologist Charles Seeger, who had also taught Henry Cowell. Ruth was the first female composer to receive a fellowship from the Guggenheim Foundation, which she used to travel and study with European modernists such as Bela Bartok and Alban Berg. Shortly after, she married Charles Seeger, who had a son from his previous marriage, Pete. Yes, the Pete Seeger.

Like Dane Rudhyar, Seeger was really into Theosophy, and really into Scriabin’s music.

To my ears though, Ruth Seeger’s music feels closer to Bela Bartok’s—and Ligeti, who was born the same year that Seeger wrote her first compositions.

Her open tonality makes the music thoroughly modern, yet it’s still melodic, and still bubbling with emotion. Some of her pieces are cute, others are hypnotic:

While others still are thrilling:

She and her husband would later work with Alan Lomax in archiving American folk music, an effort that no doubt made an impact on her stepson’s choice in career.

Carl Ruggles

If I ever make excuses about not writing seminal musical works due to the fact that I never had any lessons or training, just remind me of Carl Ruggles.

He too lacked formal training, but was making innovative modernist pieces with the best of them. His method of writing was one of ceaseless trial and error: play a bar or two, try some variations, try some more, and then some more, and determine which is best. Then go to the next bar.

This was an extremely time-consuming process. No wonder the man’s long life only yielded about an hour’s worth of music altogether!

Alas, Ruggles’ music is not really for me. His pieces heavily resemble the German modernists Schönberg, Webern, and Berg. And to me, Schönberg is like Wagner with the randomizer settings set to max. Some of it is intriguing, but only rarely does it move me.

His orchestral work is more melodic. But I can’t help thinking it sounds like chopped up Holst and Strauss. Definitely some German cosplaying going on in this music. Not for nothing did he change his name from Charles to the more German-sounding “Carl.”

Sorry, Chuck. Danke, aber nein danke…

Edgar Varese

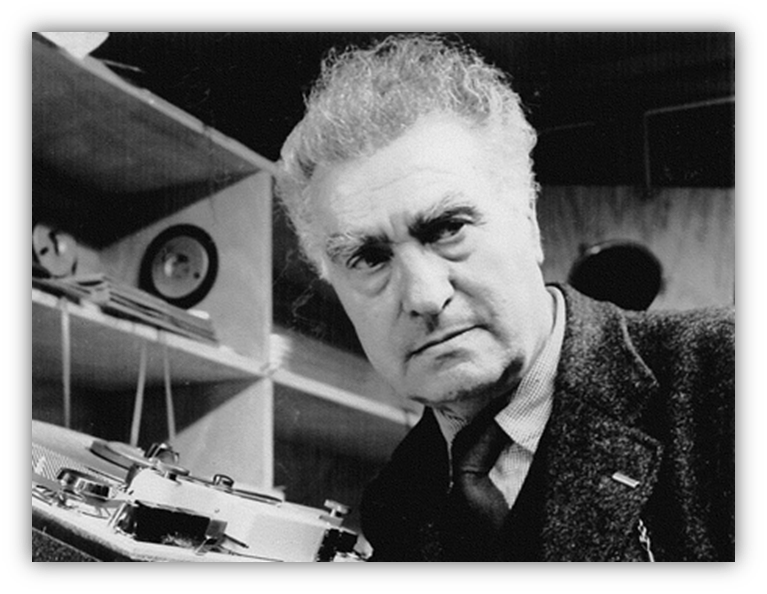

Edgar Varese was another French composer who fled to the US in the midst of the war. He was said to have been composing since the late 1800s, but that earlier music was purportedly all lost in a warehouse fire.

Whatever those older works may have sounded like, the ones written in America lay the best claim for the title of “ultra-modernist.” Unlike most modernist composers of the day, who played with open tonality or dissonant counterpoint, Varese had almost no interest in tonal music whatsoever.

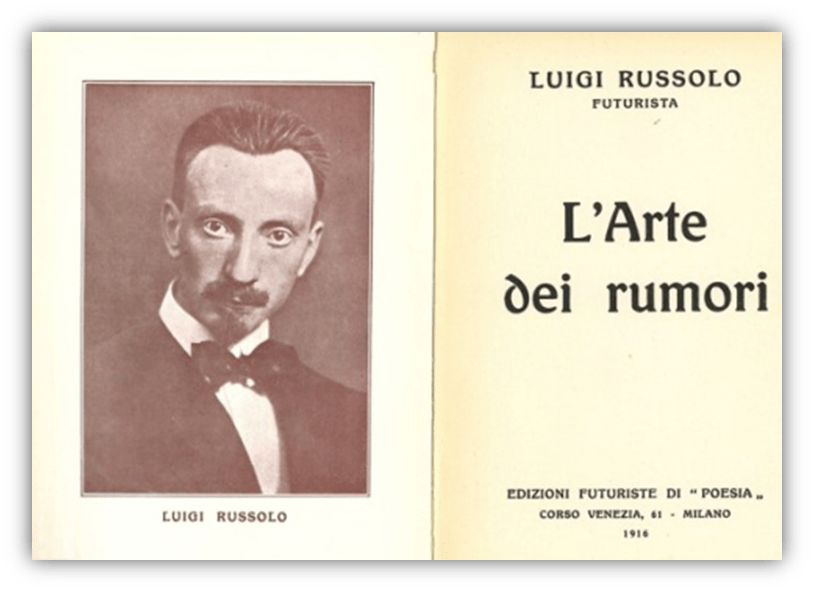

One of his major inspirations was “The Art of Noises,” the manifesto of Italian Futurist composer Luigi Russolo. Accordingly, his emphasis tended to be placed on rhythms and textures.

In many respects, Varese’s music foreshadowed the development of electronic music, and indeed, he was one of the first composers to actually include electronic instruments in his music. I often think of his works as being more like “sound sculptures” than proper music.

Then again, Varese later famously asked “What is music but organized sound?” To which I can only answer: Touché.

We’ll hear a little more about Varese’s music in future entries.

For now, just enjoy his 1921 work Ameriques, one of the most conventionally melodic works he made.

Like Charles Ives, Varese was attempting a sonic snapshot of chaotic city life, going so far as to include a fire siren in the piece. Think it sounds like the pagans from Rite of Spring wandering the streets of Manhattan?

Well, take what you can get, cuz it’s tuneless blocks of texture from here on out!

I should mention that one eventual champion of the work of Charles Ives is the late great Leonard Bernstein. If Henry Cowell was the Berthold Heinrich Kaempfert of the Ives story, Bernstein was the Brian Epstein.

I recall reading a story years ago about Frank Zappa seeking out Edgard Varese for a meet up. Varese honored the request, and if I’m remembering correctly, it was a fascinating recounting by Zappa.

I’m unable to look for it right now, but if anyone beats me to it, might make for a nice read.

A cursory search proved fruitless for me.

But indeed, my first encounter with Varese’s name was almost certainly thanks to Frank Zappa.

Is it this?

https://dadasurr.blogspot.com/2014/10/frank-zappa-sur-edgar-varese-1981.html

Boy, it sure is. That’s it exactly. From Stereo Review. Well done!

I bought Penguin Cafe Orchestra’s Signs of Life based on a Stereo Review review.

I was promised ukuleles.

Oh boy! I’m going to be clicking these links all day long. With random Talking Heads and Taylor Swift tunes thrown in.

I like the Carl Ruggles piece very much. Thanks for this!

Maybe some day I’ll vibe with Carl. He is beloved by the conductor Michael Tilson Thomas (who I somewhat recently saw do an astounding performance of Mahler’s 2nd symphony). He recorded all of his works. Unfortunately, he did not call it Meet the Ruggles.

“ Meet the Ruggles.”

Boy, you are all lucky that I’m behind the wheel today. Otherwise, there would be a ‘shopped album, cover incoming…

“His works are collages of memories, observations, and feelings–and the various pieces are rarely resolved or assimilated.”

So Ives was a latter-day DJ Sabrina the Teenage DJ?

Kind of. We’ll get into more direct ancestors soon enough, but this is as close to sampledelia as orchestral compositions can get.

Not heard any of these names before but an as fascinating as ever delve into the world beyond the norm. Charles Ives in particular sounds like a riot – his story anyway, I’ve not yet pressed play on any of the links. And Carl Ruggles methods being so painstaking that his whole life amounts to an hour of music is mind-blowing. Nevermind Axl Rose taking a decade to make Chinese Democracy or Stone Roses protracted effort at making The Second Coming. Positively prolific in the face of Carl’s perfectionism.

For a while I only knew Varese as that composer that Frank Zappa loved, and Henry Cowell as the guy that the band “Henry Cow” was named after.

Cowell is probably my favorite of this bunch, though Ives is a close second.

I only just recently got into Ruth Crawford Seeger and Dane Rudhyar, and am enjoying them immensely. I think Ives and Seeger were really important predecessors of Gyorgy Ligeti’s signature sound to be developed in the 50s and 60s. At least based on their similarity.

Perhaps Carl Ruggles could have written more efficiently if he had worked in collaboration with his musically-trained peers. It certainly speaks to his determination, but given that Ruggles was an infamous misanthrope, perhaps it speaks to other things as well.

Great article, but, in terms of the subject:

https://youtu.be/cDGlN6mluGA

I can relate, and wasn’t really into most of these artists when I first heard them. And they’re not trying very hard to be liked, so it makes sense!

But I do recommend sitting with stuff like this from time to time. Like the socially awkward loner in class, sometimes they reveal their humor and humanity to those who give them a chance. Not guaranteed, but it’s great when it happens.

Outside film, I can’t name a single female composer. I’m going to do the Ruth Crawford Seeger deep-dive.

Some people forget that Rachel Portman and Anne Dudley won Oscars for Best Original Score because there was a brief four-year period when they split the category between Drama and Comedy/Musical. Yeah, I forgot. Google forgot, too. Looking at the category’s history, perhaps, it was created with the expressed interest to acknowledge the existence of women in music, without offending the real composers. Not coincidentally, the women batted .500.

Hildur Guonadottir broke through in 2019 for Joker. The imbalance is noticeable. Between 2000-present, only three women were nominated: Guonadottir, Rachel Portman(Chocolat), and Germaine Franco(Encanto).

I wonder if this gender inequality was the inspiration behind Anne Dudley Plays the Art of Noise. When The Art of Noise was an active band, I presumed, wrong, that J.J. Jeczalik was the alpha musician.

Bjork seems suited for soundtrack work.

It’s not as if I’m self-consciously a feminist. I just know that Dudley’s original scores for Paul Verhoeven are as Oscar-worthy than some established names, whose nominations seem to be preordained.

Yeah, I hardly know any female composers.

I just looked at this list of the greatest ones, and beyond Anne Dudley (Rachel Portman is also named) I didn’t know of any of them!

https://www.classicfm.com/discover-music/latest/great-women-composers/

The ones I know are Ruth Crawford Seeger, Joanna Beyer, and Franghiz Ali-Zadeh. And Wendy Carlos, though she mostly did interpretations of older compositions. Not many at all!

Bjork did do the soundtrack for Matthew Barney’s piece Drawing Restraint 9 (and Dancer in the Dark, but that was more of a pop soundtrack). I think she’s even better suited for film than ever, as she’s been paying more and more attention to arrangements and moods in her recent albums rather than singalong anthems. It is somewhat strange that she doesn’t make more soundtracks.

LOL. Matthew Barney. I saw The Cremaster Cycle with a general audience. Cycle 3? Cycle 3, I think, features a short exercise in Tavrovsky-paced sci-fi. There is a speculative blimp. There is a football stadium with a blue turf. Some guy in the front, half-screams: “Hey! Hey! That’s Boise State stadium!”

Some people can’t believe Bjork is the creative force behind her work. I’m looking at the writing credits for Selmasongs.That’s a lot of names.

I saw Cremaster 3, and have no recollection of a blimp or football stadium. All I remember is Finn McCool, something about the Chrysler building, and the bloody rag man in the Guggenheim Museum. It’s been years, but also, I feel like my brain is the hard ground in the Parable of the Sower. All of that esoteric imagery just bounces off for those of us without a decoder ring.