The glamorous, glorious, uproarious 1920s ended with a bang, and then a whimper.

At the close of 1929, stock market prices were in a tailspin, and the resulting crash heralded the arrival of the Great Depression, a period of severe global economic hardship that lasted for a whole decade.

These times were hard for all but the wealthiest families.

For musicians, it was a time of great uncertainty, of rapidly shifting opportunities and threats to one’s fortunes.

The 1920s had seen jazz music evolve from a folk dance fad into a pop modernist phenom. For the white urbanites in juke joints knocking back glasses of hooch, those irresistible sounds simply commanded their bodies to dance.

But once Franklin Delano Roosevelt was sworn in as President in 1933, he ended prohibition. Speakeasies were effectively rendered extinct once folks could simply stay home and get hammered.

Add to this the advent of sound films in theaters, and the new boom of radio broadcasting and home listening, and suddenly the flood of possible live gigs to play slowed to a trickle. In this new economic environment, only a handful of jazz artists were able to truly stand out and make a living.

Here are a few such snapshots of success, as captured by the tech of the times.

Ain’t Misbehavin’

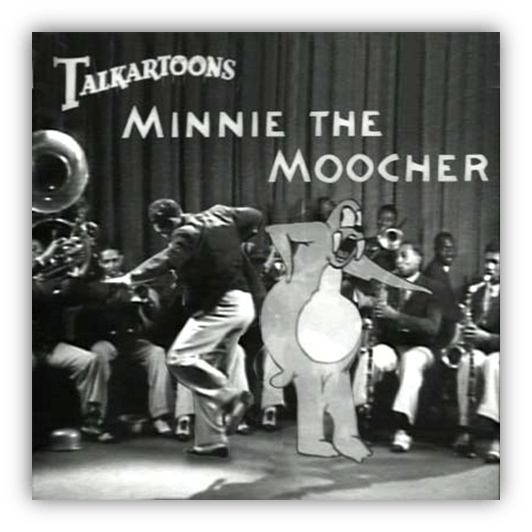

In 1932, movie theater patrons were treated to something new and oddly fascinating. In the latest cartoon short from Fleischer Studios, Betty Boop runs away from her home with her friend Bimbo, and the two find themselves wandering into some scary territory.

They hide inside a cave where the ghost of a walrus starts to sing one of the biggest hits of the previous year: Cab Calloway’s “Minnie the Moocher.”

Throughout the song, the walrus shows off some impressively fluid dance moves, while other ghosts play out a series of silly, surreal, and sinister scenes, scaring the runaways back to their homes.

Betty Boop cartoons had always been linked to jazz culture, as the character was initially created as a loving caricature of Helen Kane, an actor and singer who exemplified the flapper style of the Jazz Age. An earlier cartoon featured the jazz classic “St. James Infirmary Blues” as part of its background music.

So it made sense for the creators to eventually bring that music into the foreground, to expand on the studio’s brand as the more innovative and irreverent entertainers than their competitor, Disney.

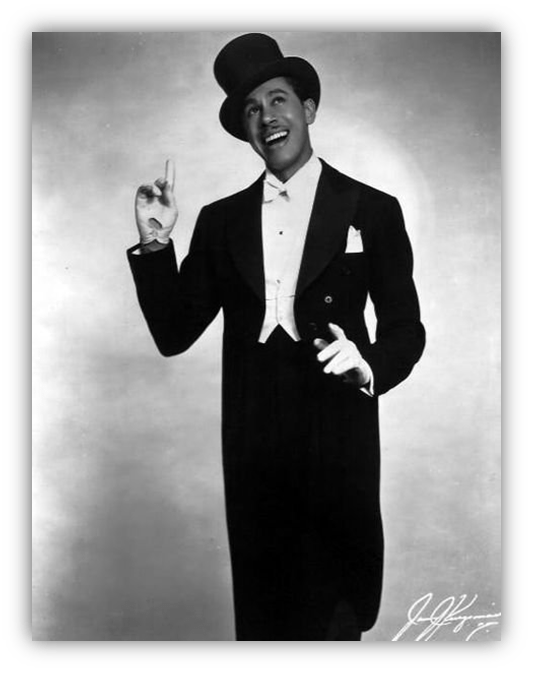

Cab Calloway had recently found success as singer and bandleader in New York City. After Louis Armstrong had recommended him for a musical revue, he soon found himself replacing Duke Ellington for a coveted residency at the Cotton Club. Cab was influenced by Louis’ approach to singing, including his use of scat improvisation, but from there he crafted his own style.

He was a powerhouse singer and a consummate entertainer, unrivaled in the skill of working a crowd, whether by leading the audience into a scat call-and-response, or by showing off his flashy dance moves.

Some of those moves were immortalized in the Boop cartoon, as the animators drew their walrus ghost over video footage of Cab dancing, a technique they had pioneered called “roto-scoping.” Cab was likely pleased with the result, as he returned for two more appearances.

Louis Armstrong would also be featured with Betty Boop, playing the disembodied head of an African native, singing “You Rascal You.” This setup was likely inspired by a video short Louis had just done called “Rhapsody in Black and Blue.”

In that one, Louis stars as some jungle prince dancing in a cloud of soap bubbles, performing “Rascal” as part of some guy’s fever dream, the result of said guy getting knocked on the head with a mop.

Very weird stuff.

Despite featuring tropes straight out of the minstrel shows, the video has a batty and edgy energy to it, and Louis really leans into that, slurring the song beyond comprehension and laughing maniacally throughout. What was perhaps the first music video was also a Dada pop-art masterpiece. And the Betty cartoon ran with that vibe.

It was a bold move for cartoonists to center their work around Louis’ song. One full of dark humor about infidelity, even featuring a wiener joke: “Just what is it you got, that make her feel so hot? You dog…”

Then again, Cab’s signature song “Minnie the Moocher” was about drug addicts.

Most of the listeners who propelled “Minnie” to success didn’t get the references, but the Fleischer brothers likely did. They were New Yorkers, hip to the latest fads and trends, and they reveled in the same sort of edgy, zany humor as Cab and Louis did.

Unfortunately, in 1934, the Hays Code imposed content restrictions on motion pictures, forcing creators to soften their works.

That included Betty Boop, who became a much more benign domestic figure in subsequent releases.

This new image was a lot less successful than the original, not surprisingly. Parents may have been frightened by what they saw in that cartoon, but plenty of white kids and teens grew more than a little curious about what happens on the other side of town.

Sing, Sing, Sing!

In December 1934, the National Biscuit Company sponsored a radio program called “Let’s Dance” featuring the music of three jazz bands.

The program lasted for three hours every Saturday evening, with hot new bandleader Benny Goodman playing the final hour.

There were many white bands playing jazz music at this time, but Benny Goodman was one of the most formidable band leaders around. Revered even among black jazz veterans for his hot clarinet sound and his demand for the very best musicianship, Goodman was determined to make a name for himself.

However, despite being an excellent player, he was not a composer, and at the start of his career, he lacked a good body of tunes and arrangements to stand out from the rest.

Fortunately, once he moved from Chicago to New York City, he met a patron who would prove crucial to his rise.

John Hammond was a wealthy socialite, a member of the Vanderbilt family.

Yet despite his upbringing, he leaned into left-wing politics, civil rights activism, and a fervent love of the hot jazz music that he had first heard in Harlem as a teenager.

In addition to playing and interviewing jazz musicians of all races as a radio DJ, and recording them for Columbia Records, Hammond provided his assistance and connections to the musicians he most admired so they could find gigs and other opportunities.

Hammond was impressed with Goodman’s playing, and he offered to help him play the hottest songs around.

In the late 20s and early 30s, Fletcher Henderson had composed intricate works that captured the hotness that he had first heard from Louis Armstrong, but tailored the sound for an entire big band.

But during the Depression, Henderson was having trouble finding work, and he was deep in debt. On Hammond’s suggestion, Henderson sold his arrangements for Goodman’s use, and Hammond also paid to have Henderson’s band train Goodman’s musicians how to play the hot style properly.

On the strength of some singles recorded by Hammond, Goodman was invited to play for Nabisco’s radio show, where he played his rip-roaring swing music in the final hour of every Saturday broadcast.

Unfortunately, this late night slot did him little favors in New York City, as most families would tune out and go to bed. And once Nabisco’s workers went on strike, the radio program was canceled after just six months of broadcasting, and Goodman feared that his shot at fame had fizzled out.

Hammond convinced Goodman to take his band on the road, to spread his sound around the country. This cross-country tour did not start out well, as the crowds were quite timid, and Goodman and his band found themselves playing traditional ballroom music rather than the hot swinging sound they were known for.

By the time they reached Los Angeles, they were ready to call it quits, to accept their failure as anything outside of New York, to end the band, and move on. But their final show, at the Palomar Ballroom in LA, was a moment of magic.

It started tense, with the band playing the boring traditionals that every other audience expected them to play.

But at the end, they decided to go out as themselves, and simply let it rip. And the crowd went wild. After all, that’s the music they had come to hear!

While New York fans of the Let’s Dance radio series missed Goodman’s music because it aired so late at night, listeners in Los Angeles heard his set during prime time, and they couldn’t get enough of this outrageous new dance band.

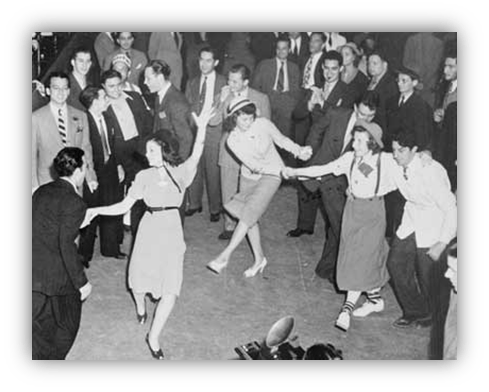

Goodman’s success marked the point when jazz went from cult sensation to national craze. Soon enough, white teens everywhere were getting hip to swing music.

They were wowed by the impeccable musicianship, the catchy, freewheeling tunes, and the wild dances.

In 1935, Goodman became a superstar for championing this strange yet irresistible music. Partly it because he was white, but it was also because his band was damn impressive. And in the midst of heightened scrutiny, he invited black colleagues into that band and they performed together publicly, a first for the time.

Thanks to the fervor of America’s youth, records sales once again began to rise after years of decline. In the heart of the Depression, the nation broke into a jitterbug, and nothing was ever the same again.

In My Solitude

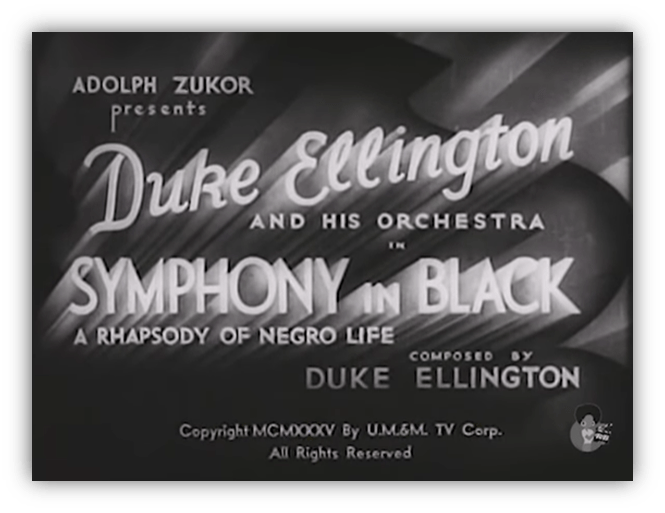

Also released in 1935 was the film short for Duke Ellington’s piece, “Symphony in Black.” Don’t confuse this one for the aforementioned video with Louis Armstrong. Despite both films having titles that reference Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, they couldn’t be more different.

Symphony In Black is all class. Which is to say, it’s a rumination on the social conditions of black Americans at the time—but also, Ellington’s understated elegance is present throughout, as always.

Beyond its multiple sections and narrative themes, the video is also notable for being the screen debut of a new vocal talent. After getting knocked to the street by her lover, a young woman breaks into song. Brought low, the lady sings the blues. Never leaving the ground, she voices her pain with a plaintive croon.

This was Billie Holiday.

Billie has stated that she didn’t like straight singing. She wanted to use her voice like the jazz masters played their instruments. Her croon was definitely influenced by Louis Armstrong’s voice, but even more, her singing was inspired by the tenor sax playing of her friend, Lester Young. Both were relaxed, reserved, quietly powerful, comfortable in their own introverted skins.

Style aside, the “Symphony” video nicely encapsulates the unique power of Billie’s music.

This was an artist who understood pain and sorrow, and she brought forth those emotions without the slightest hint of melodrama in her voice. But there was also a toughness to her.

No matter how hard or bleak her circumstances got, she never lost her sense of dignity. And that strength comes through in her music as well.

Her demeanor presented a sharp contrast from the older jazz artists, almost the complete opposite of personalities like Cab Calloway and Louis Armstrong. All black musicians had to act as pleasant and as affable as possible in front of white audiences, and often had to take undignified roles.

Cab and Satch made such roles part of their gimmick; they leaned into the camp and turned it into their form of bizarro proto-punk theater.

Billie Holiday would have none of that. She was no cartoon; she was a person, like everyone else in the audience. On-stage, she rarely even smiled, focusing instead on the emotion of the song. Off-stage? “She used profanity with the deftness of an ice skater doing a figure eight,” to quote Toni Morrison.

She also spoke truth to power, even at risk to her career.

Imagine the courage it took for her to perform and record “Strange Fruit,” her 1939 protest against the horrors of lynching. Yet she made that a staple of every show she did.

In 1941, Duke Ellington was asked to explain the dissonance in his music. He said that it embodies the lives of black men and women: “Dissonance is our way of life in America. We are something apart, yet an integral part.”

If any one jazz musician could embody that symbolic dissonance that Ellington spoke of, it would be Billie Holiday.

She suffused swing numbers and pop ballads with weighty emotional content, and hard truths. Her life would unfortunately come to spiral into severe drug addiction and an early death.

But most of her life was spent entertaining crowds with music that was without question or qualification, art. Or perhaps: changing and shaping audiences for the better with art that was generous and accessible.

However it may have started, jazz was life now.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Another gorgeous article!

There was (is?) a YT channel that I found fascinating, though he stopped updating it during Covid. He covered Rotoscoping in one of his short videos – if you have time to explore, I’d recommend his whole series:

https://youtu.be/bfXAlqx0H1g?si=NgG0jVuPsxAmlmrq

Thanks!

I also recommend this short documentary about the Fleischer brothers to get an appreciation of their craft and impact. Fantastic stuff.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xemq4sNfMf8

We’re once again covering the same stuff but from different angles. I wondered about the connection between Henderson and Goodman, but had no idea about Hammond. Good info!

I love the Ellington quote about dissonance. The story of the United States is the story of race, and the same is true of our music. They’re all completely intertwined.

Nice job, Phylum. Already looking forward to the next one!

Yeah, Hammond proved to be a vital connection for jazz musicians during the Depression. He broke with jazz once bebop came to the fore, and moved on to more explicitly political terrains with the folk recordings of a young talent, Robert Zimmerman…

As for the next one, I’d be very surprised if we overlap!

“As for the next one, I’d be very surprised if we overlap!”

Not so fast. Spoiler from the editor’s desk: it’s:

“What Makes Monaural Audio, Monaural Audio?”

and

“Dude, Where’s My Lone Speaker?”

If there’s one thing that needs to be done in stereo, it’s going back to mono.

Phil Spector has returned from the grave and entered the chat.

The boxed set came with a “Back to Mono” pin. When I threw away my backpack, I forgot to unpin it.

“As for the next one, I’d be very surprised if we overlap!”

Me too! Unless, of course, your topic somehow involves Aladdin.

I’m thinking it could be a whole new world for at least a few readers…

Nicely done, as always. From Betty Boop to Billie Holiday in a few short steps. It’s quite the journey.

Another gem – thank youi!!

Betty Boop looks so harmless by today’s standards. But if you put her in a period piece and have bygone era people react, the latent sex of Boop becomes less latent. Isn’t the “p” a double entendre? She’s wearing a strapless dress. Boo(p), wink, wink. Maybe Pee Wee Herman learned a lesson from old school “children’s entertainment”.

Among the many scenes I love from The Fablemans was the mother’s reaction to seeing young Spielberg being subjected to violence in The Greatest Show on Earth. That look on Michelle Williams’ face. It’s as if she just saw Joe Pesci stab a man repeatedly with a knife in the car trunk.

The allowance of having black entertainers sing “Strange Fruit” in public never ceases to amaze me.

Nice job, as usual, Phylum.

I don’t think that children were the main target demographic for the original Betty Boop cartoons. It was teenagers and young adults. The “boop” in her name came from the “boop-boop-a-doop” from Helen Kane’s hit song, but that’s not to say that other shades of meaning were not on the creators’ minds.

Just look at her screen debut and notice how many of the gags have a sexual charge to them:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M3_KbMd-xQU

She was the Jessica Rabbit of her time (and the creators of Who Framed Roger Rabbit were culturally aware enough to explicitly reference this fact in their film, with Betty feeling upstaged by the new toon phenom). Certainly the first time I saw Jessica Rabbit I was a child. But those “boops” were not drawn for me.

My mistake. I’m seeing something that is just a coincidence. Both lower case “b” and lower case “p” are the beginning letters of words that describe the female anatomy in slang. I know. Get my mind out of the gutter.

Thanks for the clip. I never actually sat down to watch a Betty Boop short.

Okay. Just watched it twice.

Even before her blouse makes a break for it, you didn’t see too many women lying down in beds. And when you did, there was a subtext. Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt, for instance. You see both niece(Theresa Wright) and Uncle Charlie(Joseph Cotten) in the same position on different beds. Did you see this film? Uncle Charlie wass unusually evil for a film from 1942; an actual monster. You can tell there was something between Charlie and his sister. The guy has no moral code.

Why does Betty Boop’s eyes get wide? Is it because the trombone elongates? And I don’t want to get gross. But does Mose have an orgasm? He explodes.

It’s not completely clear, but your interpretation is certainly a possibility. All of the early Boop cartoons have a bit of surrealism to them. Sometimes a trombone is just a trombone, but other times the outlandish imagery does have a subtext.

On FOX’s The Tracy Ullman Show, in a sketch that nobody bothered to save for future generations on YouTube, Ullman plays a psychologist, and admits to a colleague that she has no idea what “sometimes a cigar is just a cigar” means.

For a comedian, there is no conditional. The dick joke is eternal.

Just had a dream about Noel Fielding searching for opium dens in Chinatown.

Too much Cab Calloway on the brain!