What music best captures the people living through the Great Depression?

In those days, a popular option was to not capture it in music.

Most people wanted songs to divert their attention away from their trials and tribulations, like the glamor and energy of jazz, or maybe the sweet whimsy of pop.

Some jazz and pop musicians channeled the blues in their songs, and that was one way to conjure somber moods.

Of course, the 1930s were when talented troubadours from the Mississippi Delta and other parts of the rural South were putting their seminal brand of guitar blues to record.

These musicians grafted complex arrangements upon standard blues chords, sometimes using the neck of a beer bottle as a slide to bend their notes into stylized twangs

.More than anything, the lyrics of the songs focused on sorrow, on people falling on hard times. Of the more commercial singers, only Billie Holiday knew how to channel pain this raw.

In white America, there was the music of Woody Guthrie. In addition to being gritty and unvarnished like Delta blues, several of Guthrie’s folk tunes actually talk about the conditions of the Depression. He put particular focus on the Dust Bowl, a man-made ecological disaster of drought and dust storms (brought on by rampant overdevelopment) that consumed the Midwest. Guthrie’s songs were stark, sometimes grim snapshots of middle America at the time, and accordingly he has been dubbed “the troubadour of the Dust Bowl.”

But we’re not here to talk about him either.

For today’s entry on Depression era musical documentaries, we will be heading to the realm of weirdo avant-folk.

Ladies and gentlemen:

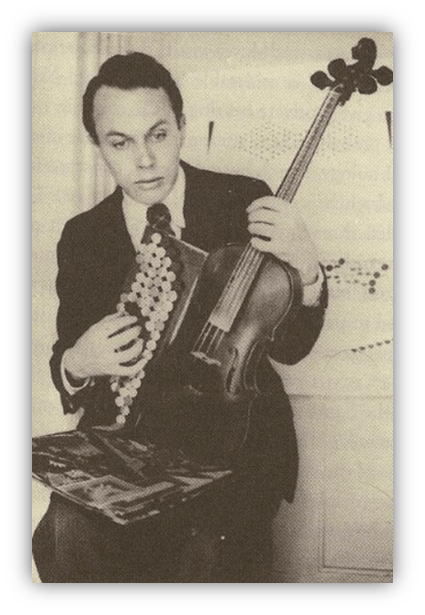

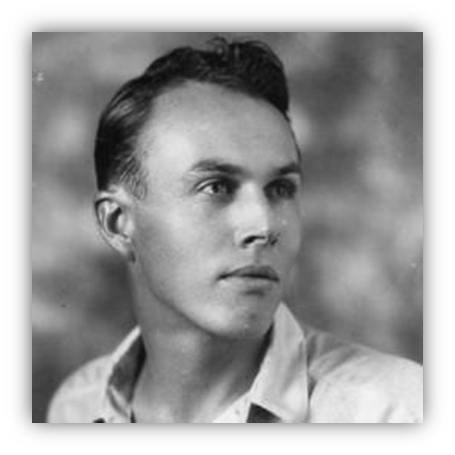

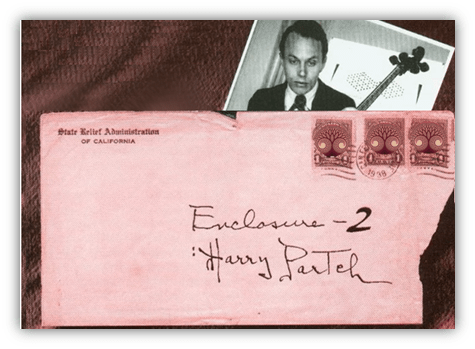

Meet Harry Partch.

The composer, inventor, and all-around outsider artist Harry Partch was born in Oakland, California, 1901 to parents who were both missionaries. Harry would eventually grow contemptuous not only of religion, but of society and conformity in general.

As a gay man living in rural America in the early decades of the 20th century, he would learn to seek freedom in absolute individuality.

Partch attended the University of California in 1920 to study music. But he soon left dissatisfied, finding the conventions of contemporary Western theory to be stifling, tired, and…wrong, for a reason he couldn’t quite articulate.

Upon reading a book by the German physiologist Herman van Helmholtz: On the Sensations of Tone as a Physiological Basis for the Theory of Music, Harry’s life was transformed.

He learned that the tempered tones of the Western classical tradition did not in fact correspond to pure tones of sound.

In Helmholtz’s work, Partch found scholarly validation for his feeling that these revered musical traditions were simply off. He would eventually come to regard these traditions as fraudulent. As a lie perpetuated by conspiracy.

“For some hundreds of years, the truth of just intonation, which is defined in any good music dictionary, has been hidden.

One could almost say maliciously, because truth always threatens the ruling hierarchy, or they think so.”

THUS SPOKE HARRY PARTCH

To create his own music, Partch largely started from scratch. He found inspiration from ancient Greek music theory, but his musical ambitions required that he develop and perfect his own musical tone system: a radical new world of sound to completely supplant the old order.

Naturally, Partch found some kindred spirits in Ultra-Modernists such as Henry Cowell and Charles Seeger, and also Aaron Copland. And in time Partch would create musical works with his unique tone system.

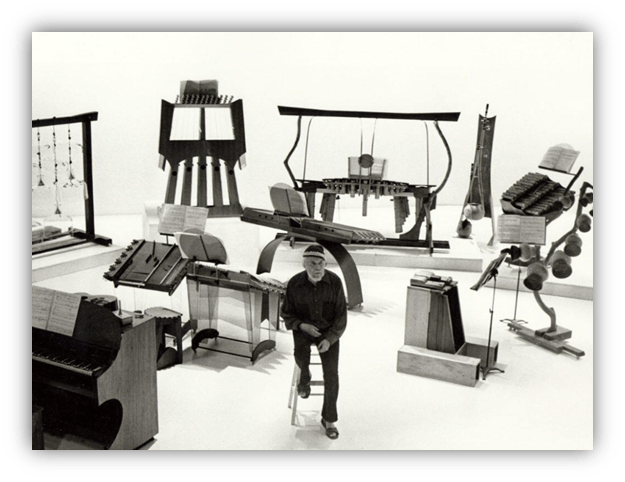

That tone system is perhaps best realized in Partch’s later career works, which showcase his many elaborately self-designed instruments. Fascinating stuff, truly, but they can also be somewhat operatic and ostentatious.

His early recordings, in contrast, are wonderfully rough pieces of oddball art.

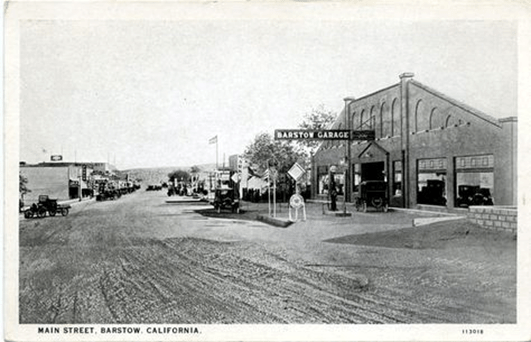

My favorite is one of his first compositions, called “Barstow: Eight Hitchhikers’ Inscriptions,” recorded in 1941.

“Barstow” was composed from notes he wrote during his years spent traveling the country as a hobo. It is a vivid collection of musical snapshots of vagrant people waiting for rides and better prospects during the Great Depression.

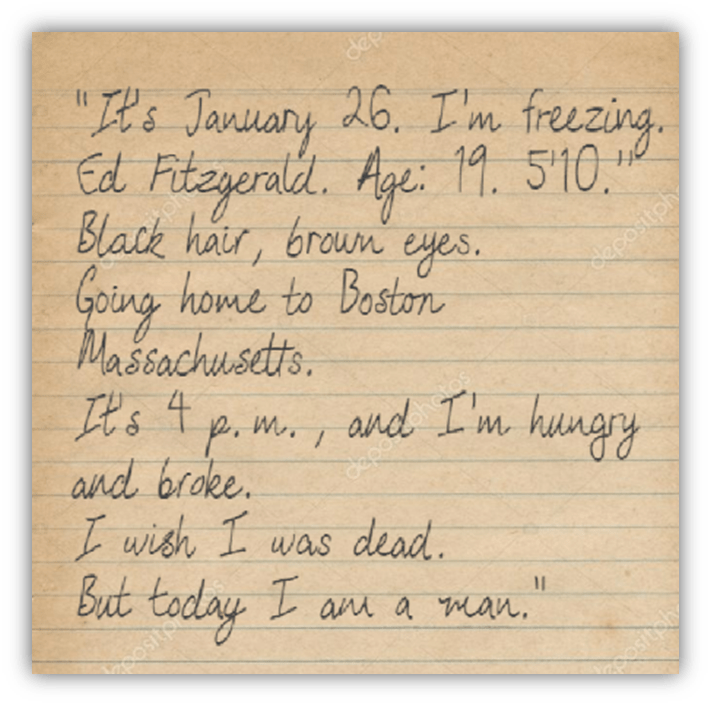

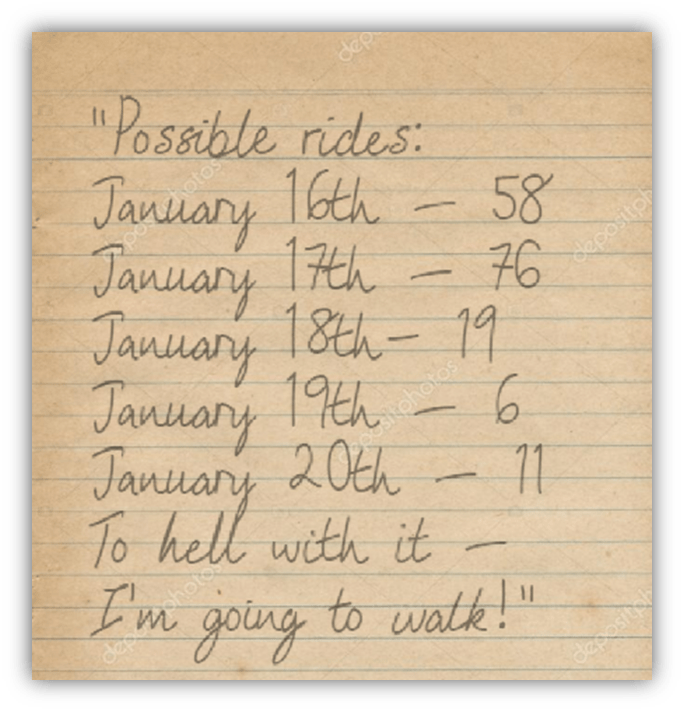

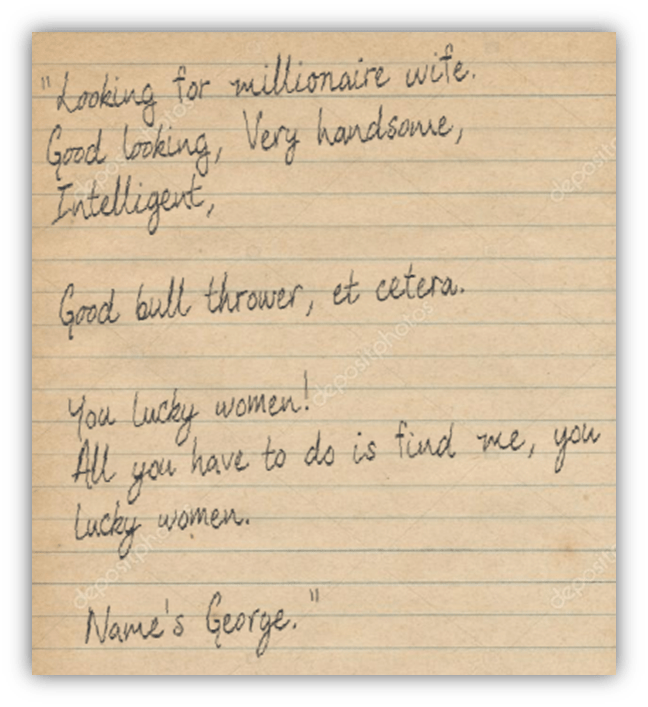

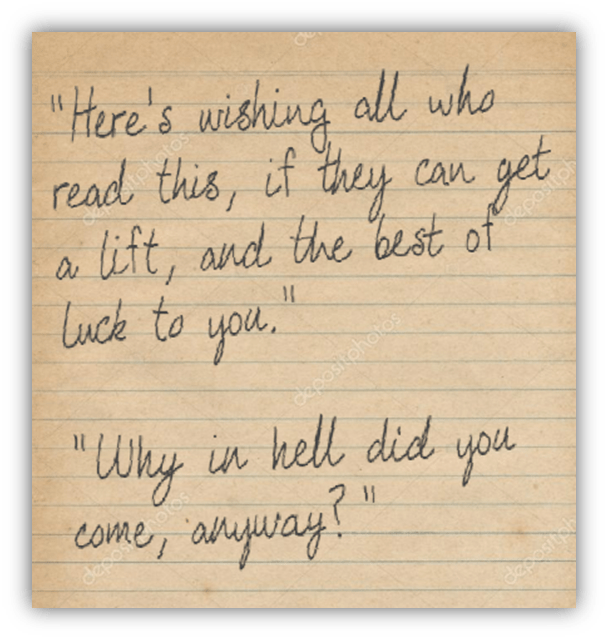

As the subtitle of the piece indicates, the lyrics consist almost entirely of writings that Partch had observed in Barstow, California during his travels. They were scribblings from fellow hitchhikers that happened to catch his eye.

After announcing the inscription number for each entry, Partch reads the inscription itself rather straightforwardly, then repeats the content in a more dramatic, singsong style.

Although the inscriptions are not without some dark moments (“I wish I was dead”) the tone is typically light (“but today I am a man”), made even more so with Partch’s giddy singing, voice acting, and yodeling.

What results is an undoubtedly bizarre, often enigmatic, but also surprisingly touching and humane portrait of an oft-forgotten folk during an impossibly bleak time.

You truly have to hear it.

The 1967 re-recording of “Barstow” is worth a listen as well. This version is much more intricately arranged, with even more of a dramatic, affected approach to reading and singing. Listeners of Dr. Demento’s countdowns will recognize parts of this one.

Partch’s radical new musical system never did supplant the work of Bach or Beethoven in terms of fame or influence, but he did sow the seeds for plenty of outsiders to come. Before there was Moondog, or Captain Beefheart, or Tom Waits, or Daniel Johnston…there was Harry Partch.

Not to mention.

Thanks to his astute observations, and his rather detached way of endearing himself to broader society, Partch was able to shed light on some transient life moments of poor vagrants, and give voice to their own words.

These people, so often neglected as nobodies, were granted pride of place in a musical work. One that brings warmth and humanity to those people and their uncertain circumstances.

Let’s all give a toast to this other Depression Troubadour and his Hobo’s guide to hitchhikers.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

There are a few documentaries about Harry Partch available. This BBC one is pretty good:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aKD3zm0WZjA

Partch had several other works based on his experiences as a Depression-era hobo. Here’s a recent performance of one he wrote in 1946. It’s neat to see people playing his unique instruments.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wjk4c8l-WJ8

Oh, and here’s a cool tour of his instruments:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9UZjhTlGT0o

Whew! An acquired taste, for sure! But the comparison to the likes of Beefheart are valid. I like to think of these types as pioneers more than geniuses. 🙂

Perhaps “Holy fools” is apt. 😀

I’m pretty sure I’ve never come across the music of Harry Partch, nor have I even heard his name mentioned until today. What he did was admirable, and his music became a voice for the voiceless. That has great value, whether or not the vast majority of people heard it or not, or how it was received by those who did. I like how you talked about how most music during the depression was entertainment whose main purpose was to divert people’s attention from the dire circumstances so many were facing. While there will always be a place and a use for entertainment and I won’t judge or put it down, music and musicians who connect with the reality of what is happening and find a way to express it, by whatever means, are vital and shouldn’t be pushed to the side because their message is inconvenient or unpleasant. Harry Partch is one of those musicians. I can’t say that his music is appealing to me, honestly, but his music is a portrait of people’s real experiences during a time that most would have rather ignored, and his story needs to be told. You did a great job of doing that, Phylum.

Interesting! I’ve never hear of Harry Partch. This is going to require a deep dive. Thanks, Phylum.

I’m sure he’s fascinating from a music theory perspective. I can’t even begin to describe his system beyond what I wrote.

Of course, my wife, who is classically trained, doesn’t find him so fascinating. And unfortunately for her, I tend to sing “Barstow” a lot…

Partch’s Damascus moment reading Hermann von Helmholtz struck a chord with me, as it sounded quite like my graduate advisor’s experience in turning to science.

He was working in DC as a lobbyist, then came across a copy of Helmholtz’s Treatise On Physiological Optics, and was completely engrossed by his exploration of physiology and visual perception. He finished the book over the next few days, and decided then and there to enter a doctoral program in psychology to explore visual processing in the brain.

Keep inspiring, Hermann!

In your opinion, is Devandra Barnhart unconventional enough to belong in the school of “weirdo avant-folk”, a Harry Partch acolyte?

I’ve seen Festival, the documentary about the 1967 Newport Folk Festival. Sadly, Partch wasn’t invited. He would’ve been 66. Is he part of the “outsider art” tradition? Is Henry Darger an accurate analog?

Also, the line about Woodie Guthrie being part of “White America” made me stop and think. I’m a little embarrassed to admit this, but I thought he was a crossover sensation, like Buddy Holly and the Crickets playing the Apollo.

Another entertaining entry.

Another opportunity for me to say “the more you know”.

I’m afraid to watch Cannibal Holocaust. Doesn’t a turtle die on-camera? But that’s being hypocritical. Every time you watch a foreign film, there is always, at the minimum, a 5% chance of an on-camera animal death, because they don’t have any Humane Society observers watching the production. If the setting is a farm, the percentage goes up to 99%.

It does, and I don’t really recommend the film unless you’re really into grindhouse exploitation stuff. Tetsuo, on the other hand, is a masterpiece. Drill penis and all.

Devendra’s first release “Oh Me Oh My” has a rough quirkiness to it that’s somewhat reminiscent of Harry P’s earliest recordings. I’m not sure if he’s a fan in the same way that I’m confident Tom Waits is. But Devendra’s a connoisseur of offbeat music, so perhaps.

I’m not sure how Harry Partch would feel about the Henry Darger comparison, but I can see the similarity. Henry Darger is like the perfect case of the untrained savant. Partch was trained, but then tried to untrain himself. Maybe he’d take it as a compliment. But only if he respected self-illustrated epic tomes about little girls being martyred by Glandolinians.