In 1892, the Czech composer Antonin Dvorak came to America to serve as director of the National Conservatory and to learn the music of the new world.

In a move that was unconventional at the time, he chose an African American student, Harry Burleigh, to be his assistant.

From Burleigh, Dvorak first heard the music of Black communities, specifically spirituals such as “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and “Go Down Moses.”

Dvorak was struck by the beauty and power of this musical tradition. He later stated:

“I am convinced that the future music of this country must be founded on what are called Negro melodies.

These can be the foundation of a serious and original school of composition, to be developed in the United States.

These beautiful and varied themes are the product of the soil. They are the folk songs of America and your composers must turn to them.”

Antonin Dvorak – 1893

Dvorak himself would incorporate the influence of spirituals into compositions for the music elite—most notably his 9th symphony, called the New World Symphony. Burleigh too would experiment with similar musical hybrids. But white American composers would do no such thing, at least not for a few more decades. The musical elite was not yet ready to recognize the dignity of the African American tradition.

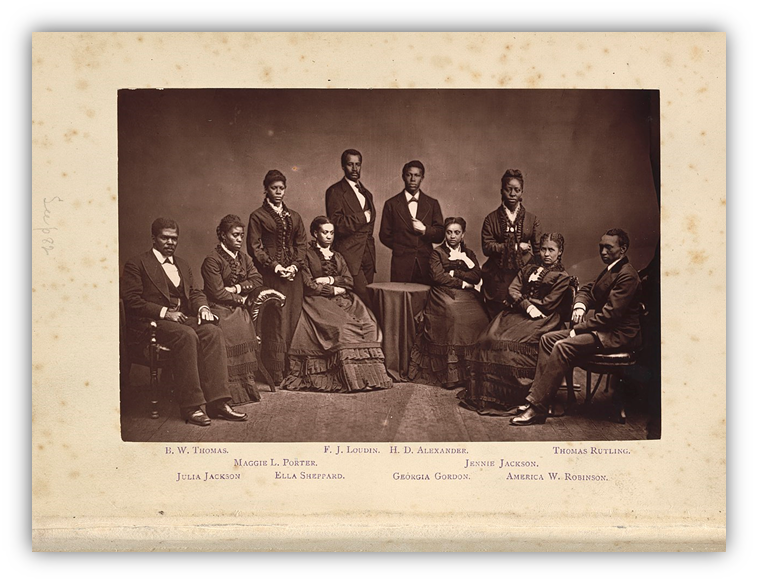

Still, in the wake of emancipation following the Civil War, there emerged some opportunities for black American musicians to actively engage with and influence the wider culture.

Their efforts helped to transform the nation, and eventually the entire world.

There were important earlier impacts, of course. The banjo was an instrument with African roots, and was made and played by the slaves in their downtime.

It grew in popularity among white communities, especially once white entertainers incorporated banjos into their minstrel shows.

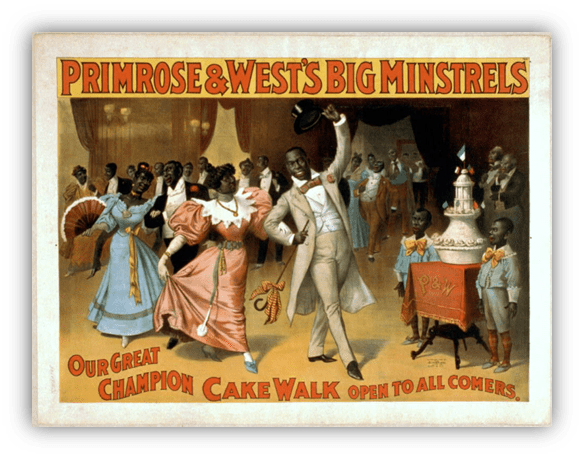

Starting in the 1830s, American minstrels began to paint themselves with burnt cork and perform the cartoonish stereotyped pantomime of African Americans known as blackface. There were other stereotyped ethnic personalities performed at the early shows, but the blackface bits were the most successful, and by the 1840s there were dedicated blackface minstrel shows.

After the war, some black men and women took the opportunity to become minstrels themselves. Degrading work to be sure, but it was a way to earn some sort of a living. It was also a way to spread their own music around.

A sound that caught on in the minstrel shows in the 1880s was cakewalk music.

Like banjo playing, cakewalks emerged from slaveholding plantations. Originally, it was a bit of reverse minstrelsy: at events, the slaves would subtly mock their masters by parading around in exaggeratedly elegant style. The masters either didn’t pick up on the mockery, or saw it as harmless fun. It became a custom for slaveholding families to hold cakewalk contests, where the best performer got a cake as a prize.

To our ears, a cakewalk means something that’s easy or effortless; a piece of cake.

That’s because of the seemingly effortless grace of the cakewalk contestants.

But it likely took those performers great skill to master their walks, not to mention great nerve to mock the men and women who kept them in bondage, who could brutalize them in an instant if something went wrong. And somehow they made it all joyful in the process.

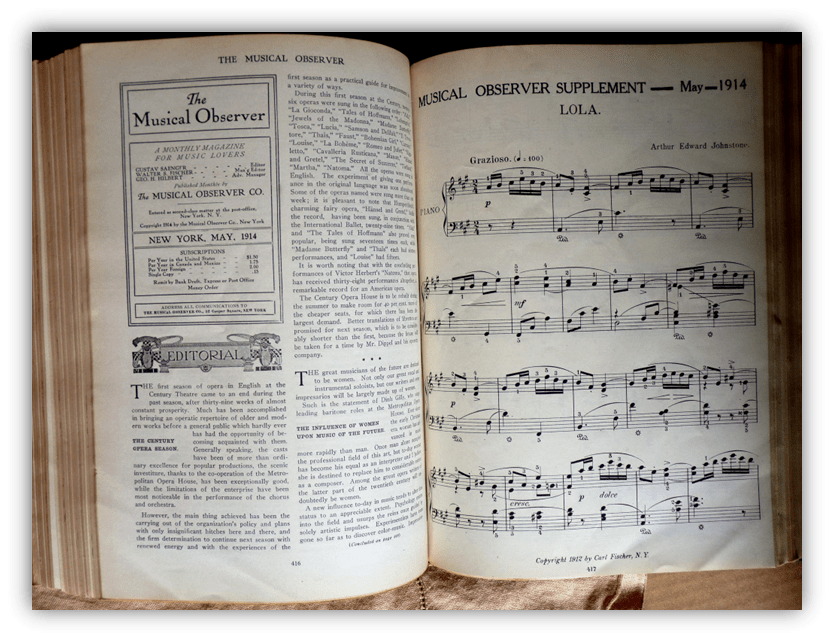

As we learned earlier from our resident musicologist, the music of cakewalk eventually came to be known as ragtime, as the prominent swinging rhythm—or syncopation—was regarded by its players as a ragged time, loose and well worn. Ragtime took the steady driving bass lines of marching band music and tied them to top melodies played in ragged time. The resulting music was lively, jubilant, and highly catchy.

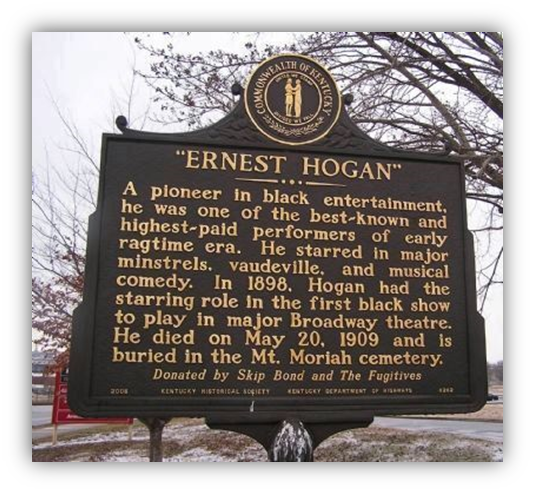

In 1895, a black minstrel performer Earnest Hogan recorded the first piece of ragtime music, and it was a hit. Unfortunately, the song was called “All Coons Look Alike to Me,” and it subsequently spawned a trend of so-called coon songs.

Considering the limited options available to black men during the Reconstruction era, Hogan’s actions seem understandable to me. Still, even at the time, black performers were angry with him for this move, and Hogan later admitted his shame for doing so. In any event, the coon song craze gave birth to the much broader popular boom that we now know as ragtime.

While cakewalk music was originally made for dancing and frivolity, it was tailored to entertain white audiences who were not themselves dancing.

Perhaps this is why ragtime music became popular as music for parlor rooms.

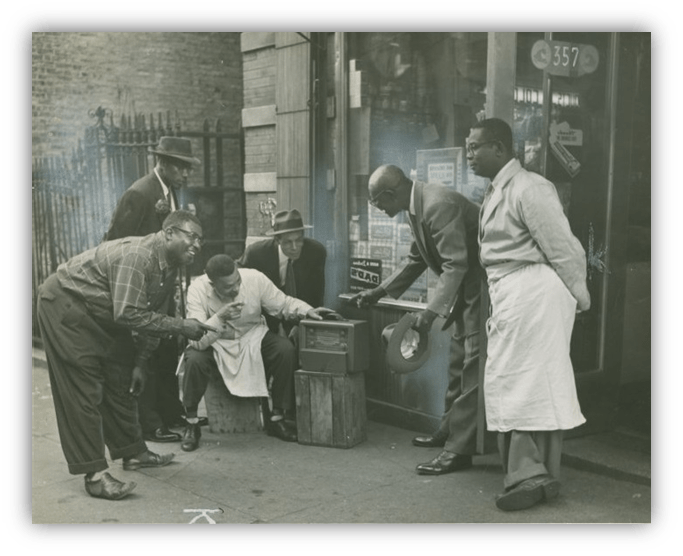

In the early 1900s, once radio broadcasting took off, ragtime became one of the most frequently played styles of music, making it a national and then global sensation.

Naturally, there were those who interpreted this new sensation to equal the doom of our culture:

Man, these prudes had no idea what other movements were stewing in black communities, getting ready to rise up and change the world.

Entertainment was the first big break for black American musicians.

But some of the most important styles of the 20th century formed when the entertainers were together playing music for themselves, on their own time. These sounds emerged outside of the spotlight of the white American populace. They were birthed in an underground of sorts, and would only gain attention later, in the 1920s and 30s.

Ragtime was an important ingredient for these sounds, but the older spirituals were as well.

Yet while the spirituals had been sung in the hope of attaining freedom, these new songs were written by freed men and women who had heard Booker T. Washington’s calls for black self-reliance.

Their songs thus began to foster a culture of individualism, even rebellion.

So began the growth of black America’s own sort of outsider art: its own cliques of debauched bohemian hipsters.

Similar to the avant garde of Western Europe, but, fittingly for a new devil’s music, this revolutionary fire would come from below.

Here’s to a brilliant new counterculture. Bottom’s up!

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

I should have also mentioned that Ernest Hogan subsequently starred in the first black musical to debut on Broadway: “Clorindy: The Origin of Cake Walk.” This too was full of brazen minstrelsy. And yet, beneath its goofy veneer, there was a confidence to it, and a sass toward white audiences, just like the original cake walk. It even had these lyrics:

“On Emancipation Day,

All you white folks clear de way,

When dey hear dem ragtimes tunes,

White folks try to pass fo coons

On Emancipation Day.”

It’s almost like the reverse of what Dvorak had said should happen, and closer to what did actually happen.

Incidentally, this was written by Will Marion Cook, a young black musician who had also studied with Dvorak!

Really great breakdown on an essential part of music history. I had never read about Dvorak and how the New World Symphony came about, and how about that prophetic quote? “I am convinced that the future music of this country must be founded on what are called Negro melodies.

Yeah, that’s pretty dead on.

This will segue nicely into Friday’s article. Excellent timing!

Blackface was simply terrible. Sure, it was a product of the times so we can forgive some of our forbearers, but a few of our contemporaries long for those good old days. They weren’t good for everyone.

I have great hope for the future, but it really can’t arrive soon enough.

Nice work, Phylum, and I appreciate the shout out.

Yes, it’s an uncomfortable history to sift through. We shouldn’t forget it by any means, and yes, some of the blackface performers, like Al Jolson, were doing their part to promote African American music in a way that the culture was ready for. But anyone who thinks of it as the good old days probably isn’t thinking very carefully about it.

I stumbled upon this fantastic poem from 1895, which perfectly speaks to the predicament that Black Americans had to deal with at the time, and for at least a few more decades to come:

We Wear the Mask by Paul Lawrence Dunbar

We wear the mask that grins and lies,

It hides our cheeks and shades our eyes,—

This debt we pay to human guile;

With torn and bleeding hearts we smile,

And mouth with myriad subtleties.

Why should the world be over-wise,

In counting all our tears and sighs?

Nay, let them only see us, while

We wear the mask.

We smile, but, O great Christ, our cries

To thee from tortured souls arise.

We sing, but oh the clay is vile

Beneath our feet, and long the mile;

But let the world dream otherwise,

We wear the mask!

In reading about some of the Black artists from the beginning of the 20th century, it was clear that some were very successful, but there was regret from some of them at the compromises that they had to make to be successful among white audiences…often playing into existing stereotypes.

Rhiannon Giddens sorta reclaimed the banjo, especially when she led Carolina Chocolate Drops.

Yes! And I’d like to enter Amythyst Kiah into the conversation as well-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PLDc1S_nbqg

I hit pause when Amythyst Kiah started singing. That’s quite a voice. Thank you, rollerboogie.

You got it. I love her. If you want more, check out her acoustic cover of “Love Will Tear Us Apart” by Joy Division. It knocks me flat every time.

Love her. She is from the eastern part of Tennessee and really retains that Appalachian sound. While also being contemporary. And also being uniquely herself.