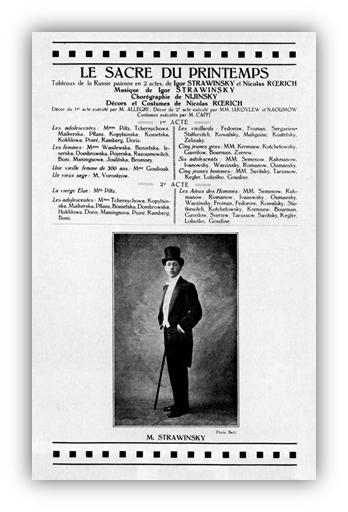

On May 29, 1913, a ballet was debuted at a brand new theater hall in Paris, the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées.

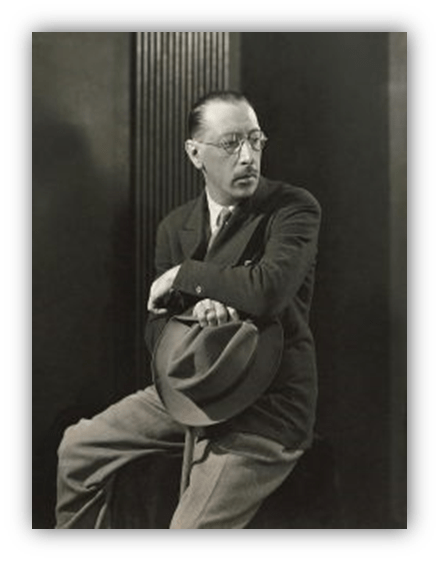

The ballet was The Rite of Spring, featuring music by Igor Stravinsky and choreography by Vaslav Nijinsky.

Those who had attended the Russian duo’s previous ballet Petrushka must have known that they were in for something unique, at the least. But many in the audience had no idea of what to expect.

As the crowd waited for the curtain to rise, the ballet’s introductory music began to play. It was the sound of a single oboe, its melody sweet and seductive. Or was it a bassoon?

Musicians in the audience chattered about what instrument they were hearing.

Whatever it was, the sweet melody curdled as additional woodwinds played a descending arpeggio that seemed to stumble around drunkenly, at once ominous and queasy. None of the parts that played on top of one another did so harmoniously.

Clarinets snaked in and out of the mess, then turned into panicked shrieks, all while the low notes of a bass bassoon jabbed with rapid staccato punches like a professional boxer going for listeners’ guts.

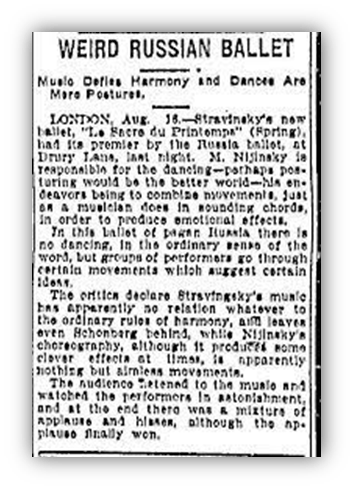

Some in the crowd cackled at this unpleasant noise, and they were harshly shushed.

Once the curtains rose, some strangely dressed figures were seen on the stage, against a backdrop of verdant hills.

Instead of lithe bodies in tights trimmed with frilly tutus, these dancers were completely covered up in rough, primitive garbs, and their faces were painted crudely.

Suddenly a loud, fierce rhythm pounded out, and the dancers jumped in unison to the tribal pulse, violently jerking their heads and limbs as they leapt. What was this bizarre, bestial grotesquerie? It was too much for some in the audience, and they began to jeer loudly. Then some angry shouts, and some fights ensued.

The event was later described as a riot, but that was an embellishment.

It was a rowdy disturbance, one that eventually required police intervention, but in fact the orchestra and dancers performed the entire ballet despite the disruption. Though the dancers needed to have their cues shouted at them to get their moves right, as they couldn’t hear any of the music over the crowd.

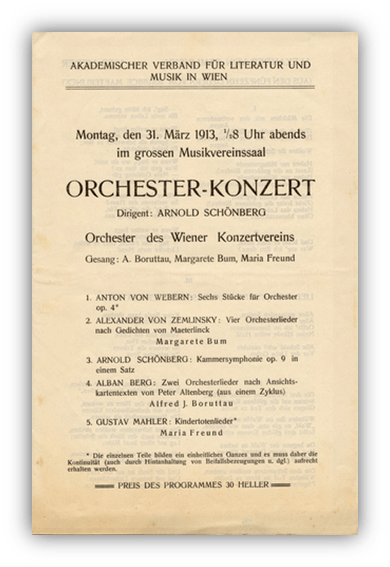

More extreme was Arnold Schoenberg’s so-called “skandalkonzert” held two months earlier in Vienna, which was canceled midway through the program due to the unrest that it incited.

Amidst the chaos, the event’s organizer had slapped a concert-goer in the face, and a snarky attendee remarked that the slap was the most pleasant sound of the whole evening. Zing!

Ladies and gentlemen: welcome to the era of modernism.

If you regard the music of The Rite of Spring with the same mix of confusion and anger as the hecklers at the ballet’s debut, don’t feel bad about it.

The work was made to be bold and unique, inscrutable, confrontational, and aggressive. As such, it’s the perfect entry point to understand the predicament of Western Europe at this time.

The first few decades of the 20th century saw some dramatic changes in technology and culture. Humans had learned to successfully fly in man made aircrafts. Ford Motor Company had begun assembly line production of automobiles. Improvements in photography and printing led to a world filled with arresting images for ads, newspapers, and books.

Motion pictures continued to expand on the wonders of special effects and editing, and some films even had plots!

Perhaps most significantly of all, radio broadcasting brought music and entertainment to the citizens of all developed nations, not to mention news of events from all around the world.

“Did you hear that an enormous British commercial liner was sunk by an iceberg?”

“What to make of the new emperor in Japan?”

“These conflicts among the Ottoman Turks sure sound worrying, but their affairs won’t affect us… right?”

Meanwhile, the artistic avant garde kept pushing for new ways to capture and excite the energy of the time.

In the early 1910s, Erik Satie was making odd, hermetic piano pieces such as “True Flabby Preludes for a Dog.” Marcel Proust drafted the modern novel, which tracked the thoughts and memories of a narrator as he went about his day.

The poet Guillaume Apollinaire was starting to write poems with the words carefully arranged on the page to produce an image, yielding a heady dance between lexical and pictorial meaning.

Then there were the painters.

Pablo Picasso was gaining notoriety for the wildly eccentric new form of painting, dubbed “Cubism” by Apollinaire.

This style eradicated traditional notions of spatial representations in a picture, attempting to capture a person or object from all perspectives at once.

Woman in Chemise Sitting in an Armchair

– Picasso, 1913

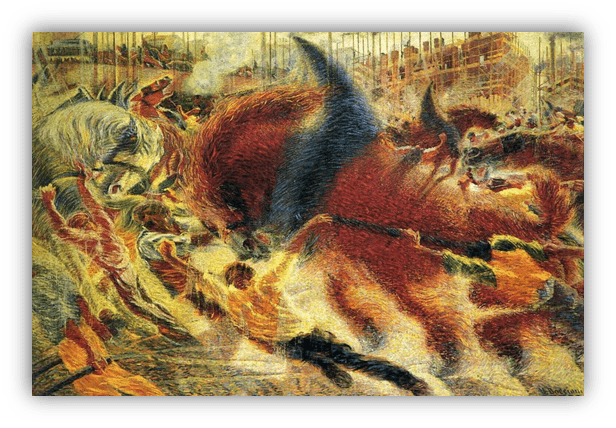

Other rising painters such as Wasily Kandinsky, Henri Matisse, Umberto Boccioni, and Paul Klee were similarly taking their work a good deal closer to what we would now call abstract art: images that correspond more to feelings and ideas rather than objects or scenes observed in the world.

The City Rises

– Boccioni, 1910

Most of their paintings at this time did still have some sort of representation there, but like Picasso’s cubist deformities, what they actually depicted took some effort to puzzle out.

A quick and easy way to understand Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring is to think of the music as somewhat analogous to the visual art at the time.

It is bold, strange, conflicted, confounding, overwhelming, and damn exciting for all that. Compared to most ballets of the time, even compared to his own work The Firebird from 1909, the music of The Rite sounds jarringly angular, more like an assemblage of cacophonous sound blocks than a sweeping musical story. Stravinsky uses prominent dissonance throughout, and even more prominent rhythm. Most ballet music strived to be lighter than air, while The Rite was heavy and physical, and tied to the earth.

The premise of the ballet is an ancient pagan ritual sacrifice to the god of Spring, wherein a virgin girl dances herself to death to bring the rains that will nourish the people.

For this reason Stravinsky thought of his work as Primitivist rather than Modernist, but primitivism had long been a vital component of avant garde art, from William Blake to Van Gogh to the Symbolists, to Pablo Picasso, who even dabbled in imagery inspired by African art before shifting to Cubism proper.

The aim in all of these examples was the same: to momentarily strip the audience from the strictures imposed by civilization (that is, to mute the repressive power of Logos) and to unleash the primal forces of passion, dreams, nightmares, creation, destruction, energy, and will.

The Rite of Spring was inspired by the art and music of pagan Russia, but it was designed as a grand rite of passage to bring in the awakening of modern society.

I’m not sure if Stravinsky had a particular future in mind; he was likely tapping into the sentiment of the time and seeing where it would take him.

Of course, there was a separate set of avant garde artists who did have a certain future in mind. These individuals mocked figures like Nietzsche for their sentimental attachments to ancient myths and bygone times.

These were the Futurists, and they didn’t want to wake the masses up to some bohemian dream.

They wanted violence.

Chaos on the streets.

Societal collapse. And war.

Only then could their nations truly advance and grow stronger.

Futurism was founded in 1909 Italy by the poet Fillippo Marinetti. Unlike his predecessors, Marinetti openly embraced modernity in every sense. He gloried in never-ending forward progress, in urban landscapes, in crowds and commotion, in pollution, in the noise and the unrivaled power of machines. He therefore sought to develop a radical new approach to art that would usher in a new age of artistic power.

The Futurists dreamed of fusing human bodies with machines. But they also wanted to transform society, to accelerate its ruin and make way for a better world. The movement started in Italy, but a rival faction soon formed in Russia to bring about their own destruction and rebirth.

Futurist artists would stage parties and performances where the actual aim was to incite violence from the audience, to amplify tension and unrest, and thus speed up the revolution. Sometimes they got only heckling and tossed vegetables.

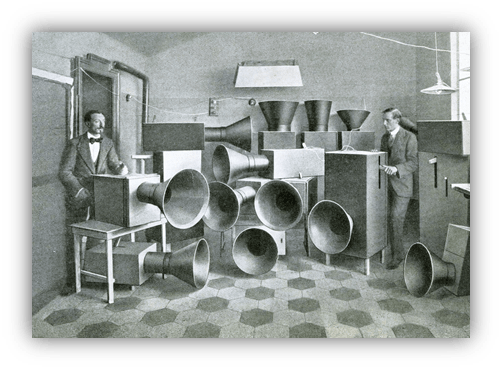

But other times, such as during Luigi Russolo’s proto-industrial noise concerts featuring his own sound machines, they got the violence they wanted.

They also, ultimately, got the war they wanted.

A Great War, the War to End All Wars.

Russolo, 1911

In 1914, rising geopolitical tensions throughout Europe and the Middle East crossed a threshold that led to the first World War. The Futurist artists excitedly joined the army and fought for the glory of Italy. Then, in 1918, Marinetti joined the newly formed Fascist Party of Italy, and helped to write its manifesto.

It seemed that there was much demand for his highly regimented program of militant masculinity and hardline utopian nihilism.

Ultimately, fascism proved to be an ill fit for the Futurists, as it depended on strong national traditions and a mythical past to keep its movement together.

Marinetti was never outright rejected, but he was sidelined from influence, and Futurism fizzled out. Those darkly brilliant works of forward progress are themselves now curious relics of a bygone era.

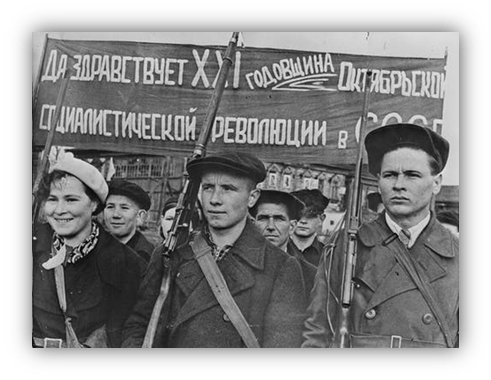

The Russian Futurists met a similar fate, with the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 completely transforming society but leaving the avant garde agitators to languish in obscurity.

For his part, Igor Stravinsky was cut off from Russia following the Communist takeover. And he remained in France and then the US for most of his life. He never publicly agitated for war or revolution.

Still, in 1930 he expressed admiration for the fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, and later related fond memories of meeting with the Italian Futurists.

This doesn’t necessarily implicate him as a fascist, but at the very least it shows how aggressive utopian rhetoric could appeal to certain enlightened bohemians in the avant garde.

The past hundred years or so of art were dedicated to unleashing primal emotions for the sake of radical social change.

Whether this change was idealized or practical, it fed into a larger political climate of rising tension, even bloodlust. Even the artists were not immune to the appeals of these forces.

The thrill and seductive power of The Rite of Spring, with its violent clamor and primal rhythms, is both the perfect embodiment of modernism in the early 20th century, and a convenient symbol of where its invocation of dark passions can possibly lead us as individuals, and as a society.

May our own sacrifices be willing, carefully considered, and meaningful.

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

For people who haven’t heard the Rite who might be interested in giving it a chance, here is my personal favorite recording of it. It’s conducted by Seiji Ozawa with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=G1-ltNoUAn8

Most performances of the Rite these days unfortunately don’t include any dancing. This video here is not complete, but it gives you a look into Nijinsky’s wildly original choreography.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jF1OQkHybEQ

And here are some proto-industrial recordings by the Italian Futurist Luigi Russolo:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IC3KMbSkYNI&t=2s

Here is a recent demonstration of his noise machines at a museum:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BYPXAo1cOA4

And here’s a recent attempt at Futurist cooking from PBS. They attempt Marionetti’s recipes for “Meat Sculpture” and “Like a Cloud.”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4v4e5WmEDtk

Finally, a correction: I wrote that Nijinsky did the choreography for Petrushka, but that was wrong. Petrushka and Rite were both productions of the Ballet Russes under Sergei Diaghilev, but Rite was Nijinsky’s first production with Stravinsky.

Oh, and here’s a great production of Petrushka. It’s not nearly as wild as the Rite, but it was getting there.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=esD90diWZds

Seems strange to consider that just over a century ago a ballet and classical music could instil such discord and a passionate response. From being brought up on rock and roll being the prominent form of cultural rebellion its instructive to see that what was being presented as the staid and refined world of classical music was not so long ago just as revolutionary. Possibly more so.

Tying into Marinetti, while I was in Italy last week we visited a small gallery in Viareggio that currently has an exhibition showcasing the life of Gabriele D’Annunzio. There wasn’t too much in the way of English translation but I picked up his involvement with the same factions as Marinetti. Sure enough just done a quick Google search and found references to them together which doesn’t exactly sound like a harmonious relationship – they had a way with an insult at least;

“d’Annunzio will say of Marinetti, to his friends, that he is “a thundering nonentity” or “a phosphorescent cretin” or even – it seems – “a cretin with some flash of imbecility”; and Marinetti reciprocated by confidentially calling him a traditionalist, a “Montecarlo of all literature”, “boring and anachronistic”. But in public, with clenched teeth, they will praise each other and in the infrequent meetings they will even exchange flowers, gifts and hugs”

I don’t know D’Annunzio, but it seems that he had been associated with the Decadent and Symbolist movements, which like the Futurists were also interested in accelerating the ruin of the Old Era and bringing in something new.

As for the insults, I imagine that being called a traditionalist stung even more than the eugenics-derived terms.

OK, I’m saving “a thundering nonentity” for a special ocassion. Hope I never have to use it. 🙂

That and “A Phosphorescent Cretin” should totally go on the list of band names.

Done!

My alma mater ranks relatively high in the international university rankings. #337! Woo-hoo! “WE’RE NUMBER 337!” But the lower campus/athletic department makes unforced gaffes that thankfully don’t make the national wire.

*I didn’t notice, I admit, knowing neither what the Canadian national anthem nor “The Rite of Spring” sounded like. I did notice the players on the court, though. One was bent over with his hands on his knees. The other one was covering his mouth. So I knew something went awry.

It’s a lot of work, getting classical music-literate.

Prior to Mr. Bois’ articles, I would play any piece that Haruki Murakami namechecked in his novels. But I was always interested in Shostakovich.

Wow, that’s an impressive list!

Well, despite the confusion and possible insult, I imagine that playing The Rite took a hell of a lot more effort and talent to play than “O Canada,” so hats off to your school band…

Don’t worry, films are coming soon enough!

Incidentally, the first bit of the Rite that caught my attention was a sample used as the stage entrance music on Siouxsie’s live album, Nocturne. Then I heard that same music as a sample in Coil’s “The Anal Staircase.” Only later did I learn it was Stravinsky!

Here’s the Rite Of Spring… WITH DINOSAURS!!

https://youtu.be/5Vw-fy-Gfl8

Stokowski’s rendition of the piece was on the friendlier side, but it was nevertheless a pretty bold move on Walt’s part to animate over this modernist insanity. And the visual sequence is fairly grim for a cartoon!