Last time, we explored the emergence of artists who sought to harness the power of revolution.

The revolutions of late 18th century America and France were the central inspirations for the Romantics and other bohemian artists of the time.

Delacroix, 1830

But unlike America’s overthrow of English rule, France’s revolution led to an extended period of political instability, including several other revolutionary uprisings throughout the 19th century. Sure, the ideal of revolution was swift and drastic action for the sake of beautiful progress, yet the reality was often less clear cut, more ambiguous, and a good deal uglier than the artists and poets were willing to admit.

Fittingly, the next wave of Bohemians to take their art into radical new directions would bring a revolution that is not self-evidently revolutionary to us. More like a slight detour on our forward march toward modernism.

I am talking, of course, about the Realist movement.

Rather than build on the bombast of the Romantics, this movement gave us art that was less idealized, more modest, more ambiguous, and a bit uglier than what came before.

Make no mistake, though: this movement was a radical innovation in art, and was considered quite subversive for its time. Realist paintings tended not to shock the conservatives of the day, but instead to confound them, and make them suspicious of the artists’ intentions.

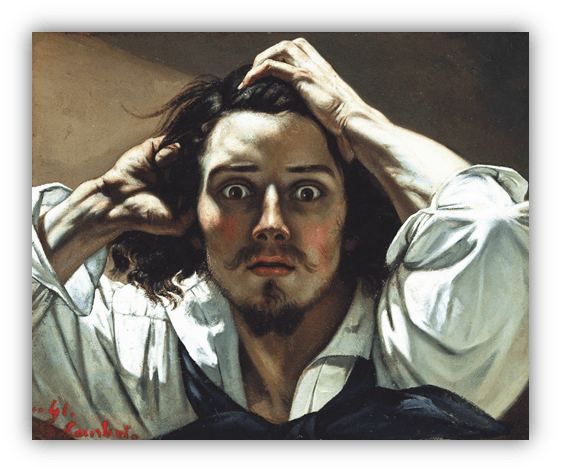

Courbet, 1845

Surely some suspicion was warranted, as these were very tense times.

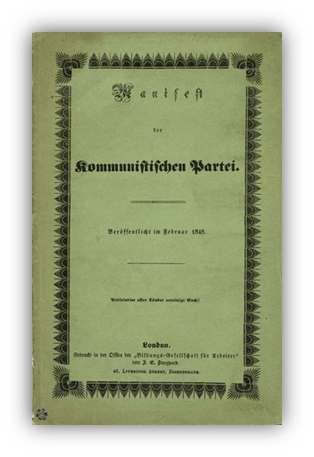

In February 1848, Karl Marx and Fredrich Engels published their Communist Manifesto in London to mobilize the working class to upend the capitalist system that exploited them.

Just one day later, a bloody revolution started in France, leading to the death of the king and the election of Napoleon’s nephew as president.

This uprising sparked similar revolutions in Ireland, Italy, Germany, Denmark, Poland, and Hungary, among other nations. Europe was a powder keg, and there were plenty of radicals hoping to provide the necessary spark.

1848 was also the year that the gifted young painter Gustave Courbet was awarded the gold medal at the Salon, the annual exhibition held by Paris Academy of Fine Arts.

The award meant that he could show his paintings in subsequent exhibitions without a selection process to determine the merit of his submissions.

Courbet used this great privilege to submit what are now considered to be the foundational pieces of Realist art.

As expected, his submissions caused a stir.

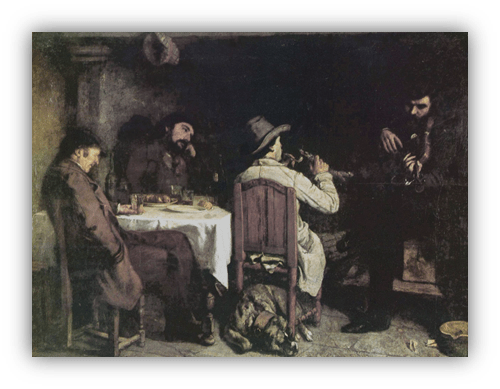

There was this one:

And this one:

And this one:

What exactly was the artist trying to convey with these gargantuan-sized paintings centered on the everyday lives of peasants and common people? On humdrum moments, quiet melancholy, or scenes of hard labor?? Why paint subjects in poses that seemed unflattering to them? Why focus on people who were plain, coarse, sometimes even ugly, rather than exalt that which is beautiful and noble and inspiring?

Courbet’s talents as a painter could not be denied, but to many his pieces were inscrutable at best. At worst, they were subversive working class agit-prop, more sparks to start another fire.

Admittedly, those paranoid takes weren’t completely wrong about Courbet the man, or his Realist compatriots. They were indeed self-styled radicals with political revolution on the brain. But a big part of what made their Realist paintings so revolutionary was not their nature as didactic agit-prop. If anything, it was its relative lack of any didactic intention that made it so radically different from what came before.

Instead, they were trying to capture the world as they saw it. No frills, no ideals, no imaginative embellishments, no life lessons supposedly drawn from history. Just individual attempts to capture life at a given moment in time.

Millet, 1857

“Painting is an essentially concrete art and can only consist of the representation of real and existing things. It is a completely physical language, the words of which consist of all visible objects,” Courbet later stated in his Realist Manifesto.

“An object which is abstract, not visible, non-existent, is not within the realm of painting.

Imagination in art consists in knowing how to find the most complete expression of an existing thing, but never in inventing or creating that thing itself.”

Gustave Courbet

Art for the Realists consisted of snapshots of the world around them. The fantastical imagination and heightened ideals of the Romantics meant nothing to them.

“Beauty, like truth, is a thing which is relative to the time in which one lives and to the individual capable of understanding it.

The expression of the beautiful bears a precise relation to the power of perception acquired by the artist.”

Gustave Courbet

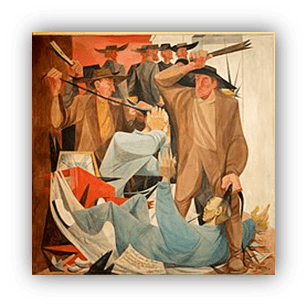

Daumier, 1864

This was a thoroughly modern way of conceptualizing art; one that reflected the growing independence of artists from the wealthy patrons who had historically supported the craft. Beyond those socio-economic considerations, it was an approach that was in many ways akin to a nascent technology of the time, one that grew and matured throughout the 19th century: photography.

Maybe a few people used photographs to reenact history or depict some mythic tale, but the clear utility of photography was its ability to capture slices of life in the present.

So too with Realist paintings.

Realist painters only sometimes cared about presenting photo-realistic images in their works. Courbet himself sought to create something like a physical sculpture onto his flat canvases, emphasizing texture and convexity with his oil application as well as color and scene layout. Other painters employed dreamier or sketchier renditions of their scenes, but overall the scenes were visual snapshots of the artists’ experiences and observations.

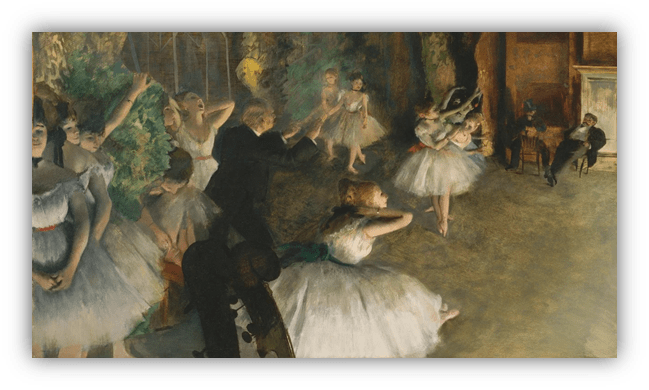

Degas, 1879

Edgar Degas is popularly considered to be an Impressionist painter, but he himself considered his work to be Realist. I’d say his work is the perfection of the Realist ethos.

Perhaps due to the growing popularity and improved precision of photographic images, painters eventually began to shift away from painstakingly photo-realistic content, and instead began to develop more obviously stylized images.

For his part, Gustave Courbet played a significant role in this new shift, with most Impressionist and Expressionist painters of the late 19th century citing his seascape works as important influences, particularly the bold strokes and rough textures he employed for his scenes.

Given the central importance of contemporary documentation to the Realist movement, it’s ironic that contemporary documentation served as evidence against the movement’s founder, to his great misfortune. In 1871, in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War, the French National Guard seized control of the nation and formed a left-wing group called the Paris Commune, which presided over the affairs of the nation for ten weeks before the French Army defeated them and restored the power of the Third Republic.

Courbet was part of this Paris Commune, and among other proposals for future plans he called for a certain public monument to be taken down and replaced: the Place Vendome Column.

Courbet was not himself involved in the toppling that later ensued, but his request to remove the statue was preserved in the Commune’s minutes.

He was captured in a photograph standing with other Paris Commune members behind the toppled column.

Once the Paris Commune was taken out of power, this evidence was later used to declare Courbet responsible for the damage done.

He was arrested and sent to prison, where he served for six months. He was released in a state of poverty and ill health. Then he was fined 323,000 francs to pay for the toppled statue.

Courbet died of liver disease from heavy drinking before the first payment was due.

Yet, his legacy lives on:

Not least because of the wealth of masterfully painted snapshots of his life and times that he left behind.

In his wake, many more artists would try their hands at slice-of-life documents of their surroundings or their lives, while others would build on his committed individualism, leading to the public puzzling more and more about what the heck a given piece was supposed to mean. For better and worse, the mentality of “It’s art because I say it is” starts here.

If you’re inclined to think of that later work as bratty and indulgent, consider a possible alternative:

After the Bolshevik Revolution, the Communist Party rose to power in Russia.

Once the regime was stabilized, the artwork they came to endorse was called Socialist Realism.

Though unlike French Realism, this was true agit-prop: idealized, simplified, and allowing no room for interpretation.

With Courbet’s Realism, as with its later descendants in modern art, the ambiguity can certainly be puzzling. Yet from that ambiguity there is the freedom of nuance, complexity, discourse, and the ability to question.

That’s an approach that gives reality its due respect. Let’s never take such modes of active cultural engagement for granted…

…because we never know what our contemporary snapshots may look like in the decades to come…

…to be continued…

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Be it by way of comment or article, I always learn something new from Phylum.

Thank you for the fantastic art history lesson.

Thanks, I’m learning a bit myself! I only knew a little about Courbet until recently, following associations that will come up later.

I don’t think I mentioned it, but this new series is my way of reviving the blog project that I had been doing on industrial and transgressive music. I stopped writing, and wanted to get it going again. Some of the posts will be reworkings of stuff I already wrote about, and some will be completely new entries. This is an example of the latter, as are the next three entries…

Is it just me or is Le Desespere a ringer for Johnny Depp?

Coubert’s seascape is particularly captivating. Captain Jack, just out of shot thankfully.

Fascinating to see the historical context and consider the impact that artists could have on the times and how that has arguably decreased now that other cultural activities like photography and film have replaced it as the most prominent and accessible forms of visual representation.

Fascinating stuff as ever Phylum.

That Desespere subject is actually Courbet himself! Maybe Depp can play him some time. His life would make for a fascinating film.

For much of the leading of edge of art (particularly but not exclusively in regards to painting) going forward from this time period, it feels like the responsibility for considering ‘beauty’ or ‘meaning’ has shifted to the observer. If they take it.

Precisely. For the abstract painters, the meaning was in the act of painting in and of itself. Once they were done, they were done. If the audience needs meaning, they’ve got to come up with it on their own, and a title like “Untitled No. 27” doesn’t give you a lot to go on.

I’m looking forward to the abstract era!

Perhaps the observers thought so, but the artists themselves felt that they were the tastemakers in terms of what beauty could be! Sometimes they cared about how the public would think, and other times (especially later) not at all.

So Gustave Courbet wasn’t accidentally political like the filmmakers who spearheaded the Italian neorealism movement. Would it be fair to say that he bit the hand that fed him. I need this part confirmed: Was the Paris Academy of Fine Arts expecting Courbet to depict the bourgeoisie? And not, oh, by all means Gustave, start a new art movement on our dime. Knock yourself out.

If the Italian war machine left the studios intact, there would be nobody to inspire Martin Scorsese. It looks as if unforeseen circumstances made Vittorio de Sica’s career. The Children Are Watching Us, which I am now motivated to watch, was made within the studio system and depicts the middle class. Who knows? Without the war, maybe DeSica would churn out any number of serviceable but unremarkable films. Because a studio system doesn’t make allowances for auteurs. Or you smuggle, as Scorsese likes to say.

“Though unlike French Realism…”

Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game can be interpreted as either a celebration or criticism of the rich. Wikipedia describes the film as an example of “poetic realism”.

Good stuff, Phylum.

At that time, the fine arts establishment did not appreciate the discreet charm of the proletariat. We need more portraits of rich fops sitting in chairs!

This Courbet fellow sounds like someone I’d like to have a beer with. I always loved that mid-19th century realism… the grit and prose of life for everyday people. And I also love the impressionism that it spawned for different reasons (I was a HUGE Monet fan in high school).

Loved today’s article and anxiously awaiting the next chapter! Thanks Phylum!!!

Courbet kept very interesting company, as we’ll eventually see. If you could have taken him up for a beer, you probably wouldn’t remember much of the night!

It’s like cinemaphiles categorizing movies over the years – 80s Action Gung Ho movies = ReaganEra sensibilities, 50s film noir reflected Cold War fears and post war traumas, etc. No matter the artistic outlet, it’ll always reflect the general trends of current society. Is that what art museums have been trying to get through my thick skull all these years?!!

A thumbs up from me and a fin up from my buddy Manny the Manatee on another excellent chapter.

There are some outstanding exceptions to the larger rule, but most art museums tend to treat their space more like zoos than a space for guided education.

“Oh let’s see what the still life paintings are up to today!”

“Just sitting there…again.”

Unfortunately for the paintings, the manatees have got them beat.

That’s generally what I shared with my students, and I used Batman as a way of showing it; from the Cold War superhero to the cartoonish 60s series, then finally to the series of movies and reboot with its “rugged” protagonist. Each said a LOT more about the period of time American culture was in rather than a winged superhero.