Take some time to read the scenario below and try to decide if the people in the scenario did anything morally wrong:

“A family’s dog was killed by a car in front of their house. They had heard that dog meat was delicious, so they cut up the dog’s body and then cooked it and ate it for dinner. Nobody saw them do this.”

I can see those gears in your head turning.

Okay, how about this one?

“A man goes to the supermarket once a week and buys a chicken. But before cooking the chicken, he has sexual intercourse with it. Then he cooks it and eats it.”

(Don’t judge me, this is science! Blame Jonathan Haidt, not me!)

Are these actions morally wrong, or are they simply non-conventional behaviors that just personally kind of gross you out?

Well, the answer you get will depend on who you ask!

Jonathan Haidt intended his book The Righteous Mind to be read by people of all sorts of moral persuasions, but I think he knew that the vast majority of readers would end up being educated liberal elites, the type of people who love to gain new perspectives via TED talks. When reading his book, it becomes obvious that Haidt himself is such an educated elite, with many of the same desires and assumptions.

So it’s no coincidence that he structures the central lesson of his book’s second part to go against the conventional moral order of liberals:

“There’s More to Morality Than Harm and Fairness”

Much of the moral psychology research that came before Haidt was centered on harm and fairness, as Haidt recounts in his story of how he came up with his own questions and theories.

The strange scenarios I included at the start of this post were constructed by Haidt with harm and fairness in mind. Specifically, he created what he called “harmless taboo violations,” fictional situations where unsavory actions were committed, but no other party was affected by or even aware of those actions. It was a way to see how people’s moral reasoning worked when harm and fairness were taken out of the equation.

Haidt concluded that the old theories of morality were lacking: at very least, they didn’t really describe morality as all communities saw it, just how certain communities saw it.

He found several groups of participants who tended to conclude that the people in the harmless taboo scenarios did not do anything morally wrong. The more Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic the communities were, the more leeway they tended to give for taboo behaviors with no harm or cheating.

On the other hand, poorer communities, less industrialized areas, cultures not steeped in the Western democratic tradition, people from these communities tended to condemn the harmless taboos as clearly morally wrong.

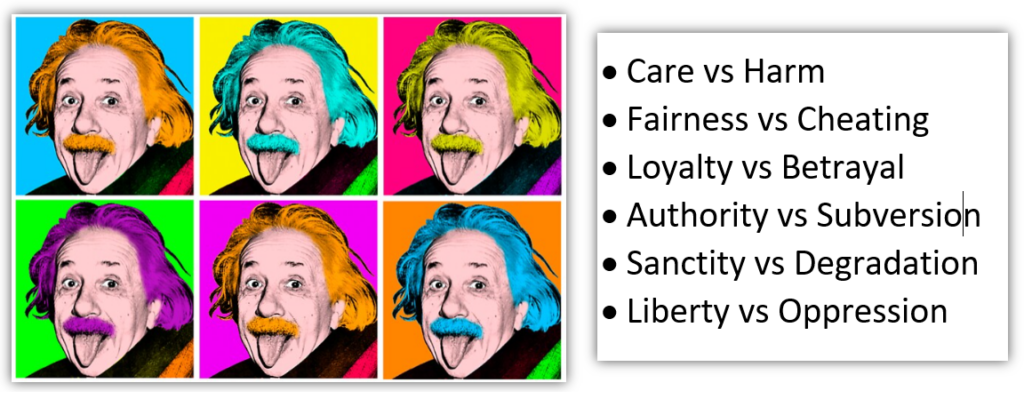

The central metaphor for Part Two of the book is a tongue with six taste receptors.

This is the basic map of the righteous mind: a sense organ that can detect distinct moral “tastes,” both pleasant and unpleasant. Based on his own and other research, Haidt has concluded that the six different types of moral tastes are (in both positive and negative forms):

Now, all humans have these six different moral taste buds, all of us can feel positive or negative intuitions in any of these six dimensions. But different regional “cuisines” across communities can accentuate different “flavor” combinations. And so different moral tribes prioritize the various dimensions differently.

And here’s the short of it: Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic populations tend to rate Care/Harm, Fairness/Cheating, and Liberty/Oppression as much more important than the other three moral dimensions, while poorer, less educated, less industrialized, less Westernized, and less democratic populations tend to rate *all* of the dimensions as equally important.

It’s not to say that Ivy League undergraduates don’t feel flashes of disgust when contemplating the scenario of the man and his chicken. It’s just that those moral intuitions ultimately prove subordinate to the perceived non-violation of the harm, fairness, and oppression dimensions.

As I’ve already mentioned, these “thinner” morality profiles tend to be the more liberal or libertarian ones. Can we say that the “thicker” morality profiles are conservative? Well, yes and no. Certainly, social traditionalists tend to have a broader moral profile. Anyone who fears cultural differences, uncertainty in knowledge, or cultural change.

But notice that I said that people from communities that are Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic tend to have thinner profiles. Well, much of conservative thought developed within the Western Enlightenment tradition, among educated individuals living in a democracy. What the profiles of those particular philosophers and academics look like is perhaps not yet explored. What is more obvious, though, is that self-identified conservatives in America are not so conservative in this sense anymore.

Through decades of resentment and distrust, most have divorced themselves from those old pretensions – even the politicians who came from money and good schools have to pretend to this new, anti-elitist reactionary style. And so a self-identified conservative in the US will be very likely to have that broader morality profile.

Note that I don’t think of typical right wing voters as evil or delusional, or weird, or even exceptional for human psychology. In fact, what we liberals and institutional conservatives are trying to preserve, that’s actually what’s exceptional.

That’s what’s downright weird.

Maybe now you appreciate why I kept repeating the words “Western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic.”

It spells out WEIRD!

And I think it’s important to highlight this.

Because while it represents the background of a good chunk of people these days, including myself, in the grand scheme of human psychology across lands and history, this mind set is rather…WEIRD. It’s the exception for human psychology, a convenient historical nicety, rather than the rule.

The people who offer the most cogent threats to secularism, pluralism, and even democracy, are largely people who typically don’t know any better. They didn’t get the special training that others got. There should be institutions in place for better civic education, both in schools and in national media, but they don’t exist at the moment, at least in the US.

These are people from poor or working class backgrounds, born and raised into a lot more stressors than others, usually in small towns or tight-knit communities. Even beyond educational knowledge, there is a huge gap between their daily lives and the social/cultural/moral complexity and dynamism that a secular society demands its citizens tolerate. Even ignoring the shameless demagogues for a moment, it’s no wonder these people are not so well-prepared for the weirdness and frustration of pluralistic democracy. There’s almost nothing that trains them for it.

Not to mention: humans are born with innate differences in their sensitivity to threats and novel stimuli:

- Low-threat individuals tend to be more curious and novelty-seeking, more likely to be more liberal

- High-threat individuals tend to be more cautious and familiarity-seeking, more likely to be community-minded and traditional.

Early life opportunities and even later experiences can help shape how open or cautious a person ultimately grows to be, but we still can’t choose our dispositions. And so even if all differences of opportunity, education, and experience were somehow wished away, we would *still* see individuals differ in their caution versus novelty-seeking, with some people better prepared for diverse democratic society than others.

And then there’s that matter of the shameless demagogues who profit from riling people up for their own selfish ends. That just makes everything even worse.

For his part, Haidt does note that the US Republican party, as shamelessly opportunistic as they can be, are really good at moral psychology. Much better than Democrats are, in fact. They tend to frame issues in ways that highlight all six moral foundations, making moral “meals” that taste really good to their constituents.

I don’t think Haidt quite reckons with the sheer advantage that their brazen demagoguery provides those Republicans, but it still is a fair point that any message pushed by a politician should be formulated to stimulate more than the simple harm, fairness, and oppression dimensions. Those three-flavor meals are solely for policy wonks who write for Vox (no offense to Vox or policy wonks; this is me jabbing my own general demographic).

If we want to advocate for a cause, we’ve all got to learn to cook meals that taste good to people (i.e., make passionate and inspiring moral arguments)…

… while also avoiding the poisonous additives that the competition likes to use.

Be as effective as ethics will allow!

tnocs.com contributing author Phylum Of Alexandria

So, an important question remains: what happens when people are excited—or turned off—by a particular moral meal?

Put more plainly, what are the group-level dynamics of moral psychology?

…stay tuned for Part Three.

Let the author know that you appreciated their article with a “heart” upvote!

Hmm … lots to chew on here. (I was repelled by both of the initial scenarios beyond the yuck factor, but I need some time to discern why that was so … initially I would say both violate my sense of soul — in the first case, both the family’s and the dog’s, in the second, the man’s … and yet, I do understand that this is my own take on it, and others can and will have other takes.) I’ll see whether I feel different upon more reflection.

I’d rather keep such reflection to a minimum…particularly chicken guy. *blegh*

In terms of Haidt’s moral foundations (the 6 taste buds), the dog story would be a mix of loyalty and sanctity violations, eating the remains of a loved one. We might excuse such behaviors in circumstances of extreme starvation, but not for the sake of foodie curiosity.

The chicken story is a sanctity violation, but the taboo feels even stronger for me than the dog example, the act much more degrading. Why that would be is not something that Moral Foundations Theory is designed to unpack, but it’s interesting, and possibly important, to ponder.

Is there any research into whether people who are highly sensitive to threats are more likely to be threats to others? And if so, which came first, their sensitivity or their threatening nature?

I’m not an expert on the topic, but researchers like Karen Stenner have studied authoritarian dynamics and traits quite extensively. People who are threat-sensitive are more likely to engage in authoritarian social dynamics, both interpersonally (such as authoritarian parenting style) and collectively, if they feel their identity or way of life is under threat.

As I mentioned, we all start with an innate disposition putting us somewhere on the scale of threat sensitivity, biasing our early development. But early life environments and opportunities are crucial, and even later life developments can help us down one path or another.

Finally, I thought it was a bit off-topic for my post proper, but I should mention that threat sensitivity ain’t all bad. In the instance of a real threat, these people tend to be the most committed to acting on behalf of those they love–and in groups, they tend to be the most cohesive and efficient at collective action. The problem for the most threat sensitive is that they are not so well equipped for the various frustrations and complications of a diverse, democratic society in peace time. But give them a real threat to deal with, and they will jump in with valor and self-sacrifice for those in their group.

Whereas we liberal cosmopolitan globalists, we love everyone equally, just not all that much. And collectively we’re a herd of cats. 🙂

Its fascinating stuff. I’ve read it twice to make sure I follow. Which isn’t a criticism at all, more that I needed to get my brain in gear to take it in. Something that interests me is adjacent to the point about how the WEIRD see these issues from a different perspective to those from a non-WEIRD society. I wonder how a non-WEIRD equivalent to Jonathan Haidt would see things and whether that would tally with his assertions but from the opposite perspective. Maybe its overthinking it to wonder if the fact that its being written from the WEIRD perspective carries an innate if inadvertent bias in how he views other societies as operating.

Looking forward to exercising my brain again with part 3.

Thanks!

I think Haidt would agree with you that his view is biased, and probably very much biased by WEIRD considerations.

Still, in his defense, he tries his best to push against those biases, and fought quite vociferously against more established moral psychologists who asserted that the only way to be fully morally developed was to adhere to what were essentially liberal/WEIRD moral codes. Certainly if we’re talking about the best way to live in a diverse WEIRD society, that would be the best way…but they were trying to pass it off as the peak of human development more generally.

On a non-WEIRD equivalent of Haidt, I wonder if something like that is even possible! People open to other points of view tend to be curious and questioning, live in diverse societies, and learn ways to challenge their perspective. Such a person will almost by definition, be WEIRD! The less WEIRD one is, the more they tend to think that their way is the only way.

Though maybe what you’re thinking is something closer to what I mentioned about institutionalist conservatives, people who are rooted in Enlightenment values (and so are fairly WEIRD), but who advocate for more traditionalist and collectivist considerations, albeit within a liberal framework. Maybe someone like David French, or David Frum, or Ross Douthaut (all Americans, apologies if they’re not so popular in the UK)?

I think Haidt is eager to learn from such individuals, and indeed has admitted that he’s since shifted his views a bit since writing the book, not as far to the left as he used to be, though still plenty WEIRD.

Sophie: I wouldn’t eat a domesticated dog.

Frances: You just say that because they’re cute.

I’m thinking of Okja right now. Okja is a girl’s pet; a super-pig. The pig isn’t cute; the girl’s love for the pig makes it loveable. Late in the film, you see a whole sea of super-pigs. Most people aren’t going to eat industrial farm-raised(I’m using my own dog as an example: Would you eat me?) Pomeranian/Maltese mixes even if they tasted good. Like a cow, it’s okay to eat the super-pig because a cow is not the most handsome of animals. Bong Jong Ho manipulates the viewer into caring about the animals’ plight, but it’s agitprop. In real life, I don’t think the fate of cows enter people’s minds.

If you substitute “family’s dog” with “family’s chicken”, nobody will blanch.

Still need to watch Okja! His Parasite was great.

Maybe it’s a different type of agitprop, but man, the slaughterhouse scene in Fassbinder’s In a Year of 13 Moons really made me care about the fate of cows.

Haidt actually goes into the psychology of cuteness in the book, and how it relates to the Care/Harm foundation.

Sarah Vowell writes about how “art films” exhaust her in her first essay collection The Partly-Cloudy Patriot. Vowell cites Fassbinder. In a Year of 13 Moons might’ve done it.

Scenario #2

If you believe that animals have souls, then the person’s behavior becomes problematic; you have a ghost chicken. The chicken already endured one trauma, being processed, and now adding insult to injury, undergoes a second trauma, being violated.

Well, hopefully even people who don’t believe animals have souls find chicken guy’s behavior problematic!

I don’t believe in souls that survive beyond death, but I do tend to think of active nervous systems that allow an organism to process and react to the surrounding world as kind of a soul: something astounding and profound, and yet ephemeral and fragile.

That doesn’t mean I’m a vegetarian, but I do understand the value in having those older sacrifice rituals when killing animals: they helped humans to process their own sanctity violations. Of course, as you suggested above, industrial processed meat renders the reality of killing pretty much invisible for most consumers, which makes it easier for our everyday consumption, but with an enormous hidden cost that we really should be more conscious and honest about.

Phylum. You bring up many questions I used to propose in my history and geography classes. The Western nations were not afraid to send naval vessels all around the world to explore ( and, by extension, conquer) other parts of the world.

The Asian countries of the time ( the middle centuries) were less adept at sailing and tended to stay close to home. Thus making them more vulnerable to the Western countries when they arrive by ship.

So, by the theory presented, does that make more “civilized” countries more likely to explore just not our world but the universe as opposed to those worlds just trying to survive.

Which begs the question, should we use our resources to help those left behind or should we invest in the future by leaving the planet itself.

In the book, Haidt tries to describe human moral psychology as it exists, both in its generalities and in its many variations. He keeps most of his opinions well shielded throughout (and with good reason! He wants to win over readers of all different moral leanings).

But in recent years he has become more of an advocate on certain topics. I think he might agree that powerful and selfish individuals like Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg should be shipped off and sent to Pluto for the good of the planet. Or maybe he’d at least “Like” or “Share” such an idea from a semi-anonymous account. 🙂

Regardless of where we head in the future, I agree that we should understand how we got where we are from the context of history.

For what it’s worth, my music history blog does try to grapple with this notion you raised, of “Progress” and “Enlightenment” being inextricably tied to expansion, exploitation, materialism, consumerism, and other less savory things. Not that I have a clear answer or understanding of it all, but the opportunity to chew on the idea does help understand some aspects a bit better, certainly in the context of transgressive art and music, and the traditionalist reactionaries who demonize such art.

Phylum delivers another big fat juicy turkey leg to feast our minds on….😀 Much obliged for that fantastic read!

One caveat I’d throw out there (simply because I see both Rebublicans and Democrats doing a lot of questionable behavior, one side isn’t any worse than the other from my perspective) is that certain veins of the liberal agenda are just as skilled at manipulating minds they are well aware they can easily manipulate as their conservative counterparts. Honestly, it’s a whole lot of thinly veiled condescending preaching, and borders on cult leader behavior, assuming everyone they are speaking to are far less intelligent than them.

It is disgusting behavior for elected officials who are supposed to represent their constituents, not brainwash them….. and yet it is how it’s always been for all of mankind.

No, I don’t trust any politician; why do you ask??!!

A few companies ago in my career, I worked at a commercial real estate group. Every year they’d fly every employee from around the Southeast US to their HQ in Atlanta for several days of classes, seminars, etc. (The 5% of us who made maps for these brokers had our own side conference) Easiest way for all their brokers to stay current on license requirements and the like. One of the seminars they had all of us attend was a lecture from a Georgia Tech Ethics Professor. First, and so far, only time in my life I was absolutely blown away with a speaker – he was fabulous. Personable, knowledgeable, assumed his audience was at his level, engaging, and the topics he was discussing were so relevant and spot on when it came to ethics in your life. I heard sooo many of these jaded brokers at the dinner party that evening saying how terrific that guy was, and how weird it was that ethics should be common sense, only to have him articulate so clearly it is NOT common sense, and really has them rethinking their behavior. That’s a rarity, and the kind of person needed in politics. So I continue to hold out hope for such a politician, because I heard and saw THIS dude.

Man, I sound like I witnessed a future Saint perform a miracle, ugh. It kinda had that impact on me though!

Thanks, I hope people find my leg to be tasty. 🙂

I certainly didn’t intend to say that Democratic politicians are more moral people than Republicans. I mean, they are politicians after all!

For one, I think there are different incentives that motivate the parties differently. The Republican voter base is a lot less diverse and less fractious than the Democratic one, which means that it’s easier to gin up Republican voters in a way that unites most of the whole. Certainly, Democratic politicians are not above pandering to a particular group, but few such messages truly unite the whole coalition, and can often risk inter-party fragmentation. So we often get mushy, bloodless, focus-grouped talking points that are spit-shined so as not to offend any of the particular interest groups in the coalition. Yay.

They can definitely sound preachy or condescending too, but is that actually effective political messaging? Even Obama, who is in many ways a genius at communication, could sometimes sound condescending, so when the less charismatic tap into that vibe, it’s just painful.

Like Haidt I do wish that people like Biden or Chuck Schumer could master effective ways to marshal attention and inspire passion. At the same time, such an approach will always be at the risk of demagoguery. Without some way to keep a team’s perspectives in check, they might not even realize that they’re being hysterical and irresponsible: it just looks different in the bubble.

Nicely stated; I enjoyed that response!!

Nom-nom-nom….

Not to second guess Haidt or anything, but the thought that entered my mind is the individual vs. collective moral framework. Maybe this is a different way of phrasing “liberty vs oppression,” but I think it may be distinct.

Here in the US, we tend to understand the world as individuals, with individual liberties, pursuing individual gain for ourselves and a small inner circle (the family typically). We tend to have little concern for the collective, for harmony, the greater good.

Other societies (mainly in the Asia, Africa and Latin America) have a much stronger orientation toward the collective good. You as an individual matter, but mainly as part of the harmonious whole, not as a discrete entity that exists independent of the community around you. A collectivist orientation is more respectful and conformist, more interdependent and collaborative.

Maybe this is where you’re going with your next column. I feel like this “individualist vs collectivist” orientation spills over into the six moral tastes.

That’s exactly right, and Haidt does talk about research on individualistic vs socio-centric societies before he gets to his own research on moral foundations.

Probably better to second guess me rather than Haidt! I’m glossing over a lot of this stuff in my posts, so I definitely recommend the curious to read the book and bask in the details and nuance that I am surely butchering for brevity. 🙂

WEIRD societies are just that, weird. And part of why they’re weird is that they have enshrined an ethic of individual liberty, rather than a collectivist approach that prioritizes the community, or at least the family. Even within liberal societies, though, there are more traditional communities (those with broad moral profiles), and they tend to be more collectivist, more socio-centric, than their educated urban cosmopolitan neighbors. Though perhaps any American will be more individualistic and less socio-centric than rural India or Nepal.

As you suggest, individualistic communities tend to place the Liberty/Oppression foundation (along with Care/Harm and Fairness/Cheating) as especially sacred for their moral order. Collectivist communities still care about fighting against oppression, but they will be more willing to sacrifice individual liberty or wellbeing for the greater community good than us WEIRD folks.

My next post will be about the social dynamics of moral tribes, no matter what the moral profile looks like.

Very fascinating stuff, Phylum! Given me a lot of food for thought. I’m going to study what I “taste!”

Great, thanks! I hope to stimulate. And certainly hope my food for thought didn’t turn anyone away from eating chicken…