“Oh, boy.”

“Here it comes.”

“What miserable pretentious drivel does he have for us today?”

But, just stay with me…

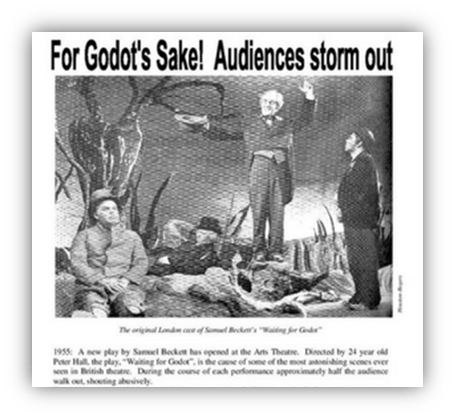

When Samuel Beckett debuted his first stage play in Paris in 1953, a large part of the audience exited the theater after the first act.

When the English version of the play debuted in London, the audience heckled and jeered before exiting early.

One person shouted near the start: “This is why we lost the colonies!”

Okay, great. So a weird, avant garde performance gets scandal points by angering its audience. Nothing new here.

But wait:

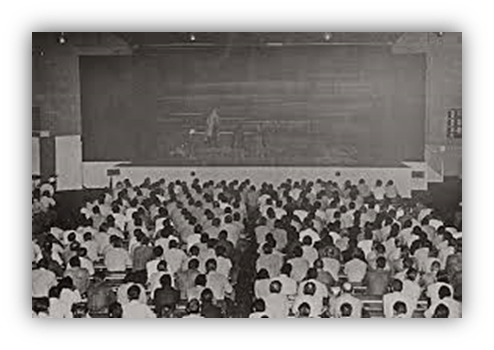

In 1957, Beckett’s play was shown to the inmates of San Quentin State Prison in Texas.

This was the first play to be shown at the prison in more than 40 years. What did these men, these convicted criminals, think of the controversial new work?

An avant garde play in which, to quote Beckett’s script: “Nothing happens. Nobody comes. Nobody goes. It’s awful.”

Well…the inmates loved it.

So why did the cultured theatergoers of Paris, London, Miami, and elsewhere respond so negatively to Beckett’s play? And what did the prisoners see in it that few else seemed to see?

This anecdote sheds some light: When the theater producers were setting up the stage within San Quentin, the set and lighting designer realized that he had neglected a crew of inmate volunteers who had been working on tying up the cyclorama. These men had finished their task, and were sitting on the scaffolding, quietly waiting for further instruction.

He apologized for keeping them waiting for so long, but the men thought nothing of it: “It’s okay, we’ve got lots of time.”

When the rest of the world saw Waiting for Godot, they grew confused and irritated by what they couldn’t understand.

When those inmates saw Waiting for Godot, they found that their own reality was captured quite well.

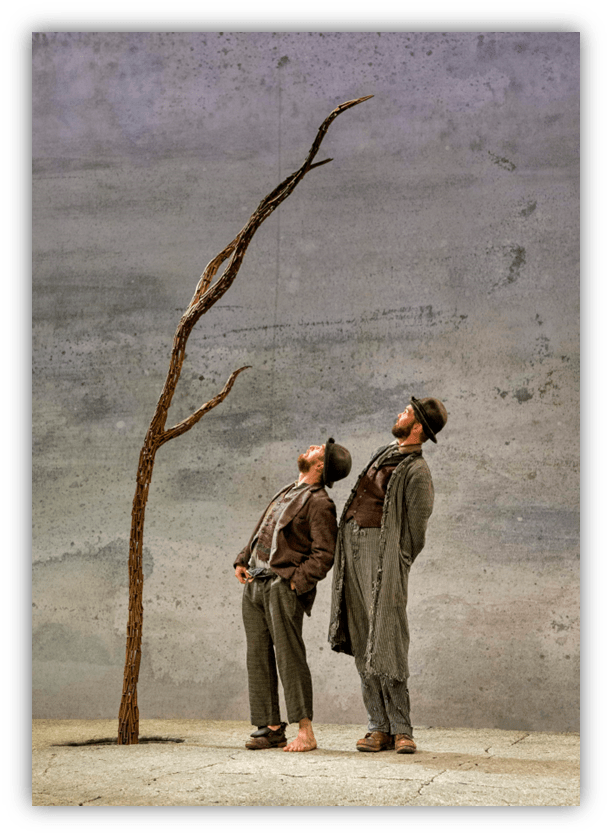

If you’re not familiar with the play, it centers around two men, standing around and waiting. For someone named Godot, obviously. The set is nothing but rubble, save for one leafless tree. The men pass the time by telling stories and bickering.

They have trouble remembering things, their sense of time and perspective hopelessly atrophied by endless waiting.

Has it been weeks? Years? Decades? Who knows? They even contemplate suicide more than once, as a way to pass the time. It’s funnier than it sounds, actually.

A few other people drift in and out of the story: a dignified man and his slave, a messenger boy with news that Godot has again been delayed. In one sense, these encounters help the two men kill some more time.

But in the play’s second act, things go from strange to outright surreal. The man and his slave, as well as the messenger boy, have no memory of meeting the two main characters before. What’s more, they have assumed completely different personas.

No matter how one interprets this narrative trick, it serves to quash any hopes of the men’s situation ever reaching a resolution. And instead, it infuses the story with a deep sense of futility. As if they were indeed sentenced to wait, on and on, in perpetuity. Forever.

Time does in fact pass, as evidenced by the lone tree, which manages to sprout a few leaves.

But for these men, nothing will ever change. The play ends pretty much as it begins, with the men insisting that they will finally leave, all while standing there doing nothing. Nothing beyond waiting, that is.

I watched Waiting for Godot for the first time not too long ago, via the film version, while at home. And: it made me feel like I was losing my mind.

There’s plenty of funny banter peppered throughout the story to lighten things a bit. Not to mention some literal gallows humor. But more often than not, the story pushed me into uncomfortable places. The incoherence of the dialogues. The uneasy silences. The constant uncertainty and ambiguity. The rapid shifts from mirth to misery.

And, most of all, the complete absence of any resolution to the men’s predicament. All of this raked at my mind. I felt like the men were two damned souls trapped in some absurd hell, and I was trapped with them.

(Still, what if this hell reflects something that we all try to escape in our everyday lives?)

But first! A distraction by way of some background information:

Samuel Beckett was born in Dublin, Ireland, but he bounced around the major cities of Europe in his young adulthood, where he sustained himself by teaching and writing.

He settled in Paris, where he befriended James Joyce, another expat creative from Dublin.

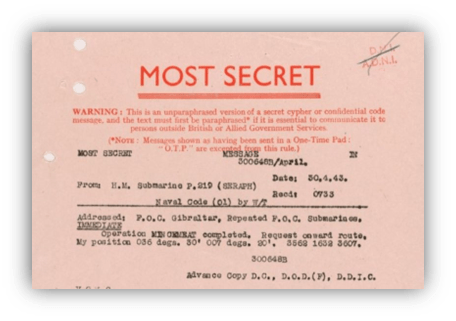

Later, when Germany invaded France, everything went into chaos. Beckett and his wife could have fled to Ireland, but they joined the French resistance.

They worked as couriers within the unit Gloria SMH. They translated and relayed messages to and from British Special Operations.

This unit was betrayed by an enemy in their midst, so the Becketts found themselves fleeing Paris to escape the gestapo. They wandered the French countryside, searching for safe harbor, not knowing who would be friendly or who might be allied with the Nazis.

This was a surreal time for the couple. One of endless uncertainty, endless waiting for something to happen, whatever that might be.

After the war, daily life in France resumed its appearance of normalcy. And Beckett began to feel as if this normal life was just a facade. A series of mundane, distracting lies to paper over harder truths.

Yet he continued his writing career.

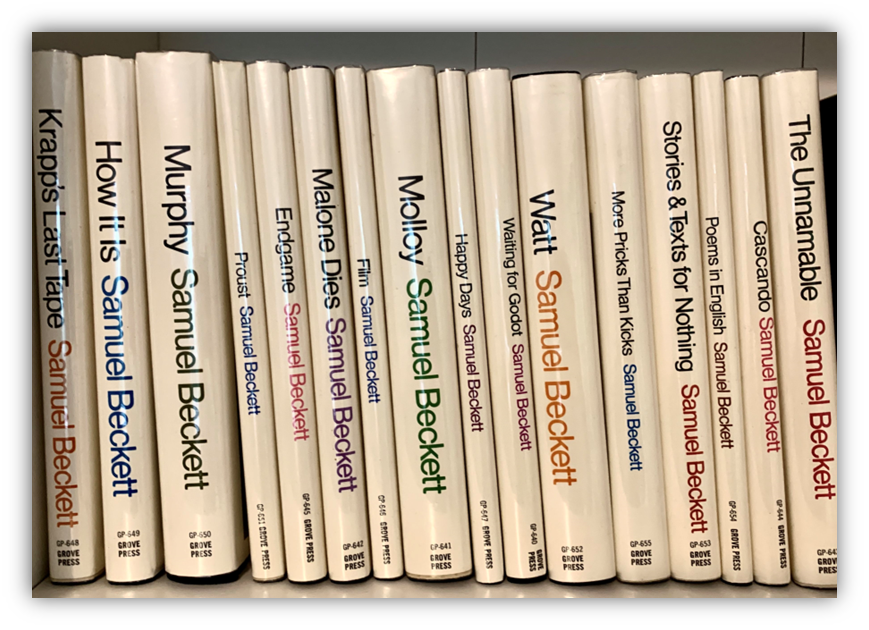

His early works were close to those of his friend Joyce: ambitious attempts to synthesize human culture into a dizzying, intricate narrative showstopper. But Beckett wanted to take a different path, to find his own voice as a writer.

He did so by stripping away the pretensions of his writing. Cutting everything down to the absolute core. Simple, plain, everyday speech. The barest bones of a premise. And compelling characters with personalities that stand out, despite not having much of a plot to showcase them.

The resulting play was so spare and unadorned that prison inmates could easily connect with it.

As for Finnegan’s Wake? The inmates might take solitary confinement instead.

Like James Joyce and Virginia Woolf, I think Beckett was a genius of human psychology.

Through their more ornate experimental prose, those earlier authors conjured up realistic streams of everyday thought. And they also alluded to more painful deeper layers that the stories’ characters did not wish to access. Beckett took this same psychological dynamic and made it the focus of his play. Yet through his hyper-minimalist style, he found a way to force audiences to sit with their own uncomfortable thoughts. To reckon with their own distracting mental banter, and what it often covers up.

Importantly, though: Beckett’s play wasn’t an act of malice. Waiting for Godot is sometimes characterized as a practical joke.

Something that treats its audience as if it were suckers.

Like the Dadaists following World War I, Beckett had indeed developed a more cynical view of human society after WWII. But despite all that, he was still rather generous as an artist. He was inviting his audience on a guided tour of sorts. A carefully designed surreal experience, so we can better understand ourselves.

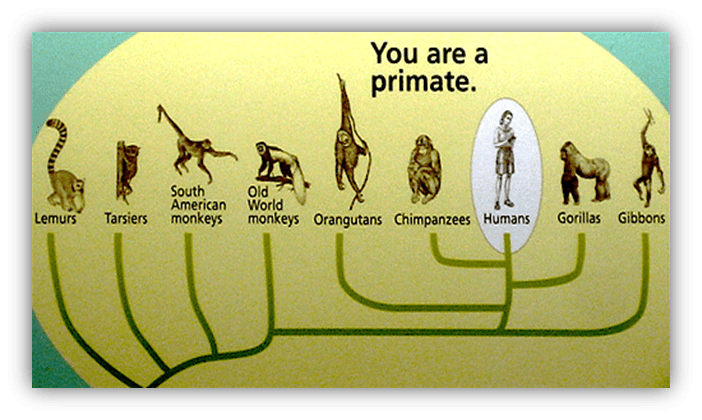

We humans often forget that we are primates. Or, we simply don’t like to acknowledge it. But the fact remains that our thinking has many aspects to it that reflect that deeper ancestry.

Monkeys and apes are foragers, constantly looking around for fruits, stalks, and other things to grab and eat. Most of them navigate through the trees, and so the need to constantly look ahead and to think ahead is paramount to primate survival.

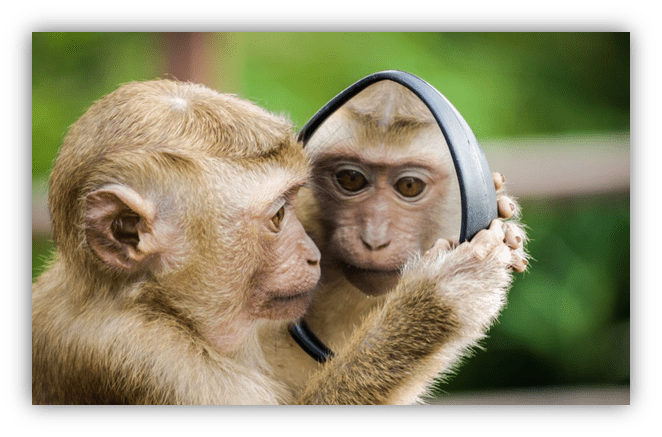

Our own constant flitting from one thought to another is one example of our “monkey minds” at work. We’ll never escape it completely, and that’s probably a good thing.

But one result of it is that we tend to distract ourselves from deeper anxieties that we have. Fears of loss, fear of loneliness, fear of death. Or despair at a world that can seem cruel, or confusing, or meaningless.

Waiting for Godot makes you sit with those feelings, for nearly two hours. It lures you in with rapid, silly banter—perfect for our monkey minds. But soon our monkey minds go crazy. We keep looking for the next piece of information, the next step forward in the story…and yet nothing reliable comes. All we get is futility, incoherence, and dread.

And yet oddly enough, it’s the gallows humor that makes it all more humane. Far from a cruel prank, the play highlights the toughest aspects of the human condition. Yet throughout it all we can share a laugh at how absurd it all is. And even find a hint of hope despite the darkness. As they say in the play:

Estragon: “I can’t go on like this.”

Vladimir: “That’s what you think.”

Beckett is revered as the progenitor of what we now call the Theater of the Absurd. An informal movement of playwrights who sought to highlight the inherent absurdity of existence, especially in modern life.

Now, seven decades later, we live our lives in a hyper-modern society, with an omnipresent culture industry. Needless to say, it has become easier than ever to distract ourselves with comforting amusements. To gorge our monkey minds on a ceaseless stream of sights and sounds as sweet as the juiciest fruits in the jungle.

Dig in, I say.

And enjoy. But once in a while, maybe try something more medicinal. More therapeutic.

You’ll thank me.

Here’s a quote I like from the graphic artist Alan Moore, made in 2003, on the nature of art:

“In latter times, I believe artists and writers have let themselves be sold down the river. They’ve accepted the prevailing belief that art and writing are merely forms of entertainment.

They are not seen as transformative forces that can change a human being, that can change a society. They are seen as simple entertainment.

Things with which we can fill 20 minutes, half an hour, while we’re waiting to die.”

Alan Moore “The Mindscape of Alan Moore” – 2003

Whatever its other meanings may be, Waiting for Godot is all about waiting to die.

It’s a long, tedious, desperate wait. It’s so long that we grow conscious of that wait. There are distractions aplenty, but they all prove flimsy and fleeting.

What we’re left with is endless, almost timeless waiting.

Waiting around for that uncertain end to come swooping in for us. That’s the reality that we all try to avoid.

Yet it’s good for us to sit with that reality. If only for a while. And try to process the feelings we ascribe to it.

Just as ice cold showers provide our primate brains with benign stress that can help treat mood disorders, so I think that Beckett’s plays provide benign stress conditions that help us process the existential angst that underlies our everyday thinking.

We don’t need to spend years locked in a literal prison to get the benefit of a changed perspective. You could try Zen meditation, or mindfulness training.

Or maybe just an hour or two safely trapped in an unnerving limbo, via an absurdist play.

As a wise man once said: “Freedom of mind comes to those…“

Let the author know that you liked their article with a “Green Thumb” Upvote!

Thoughtful stuff as ever. I read quickly so I have to make an effort to slow down sometimes and make sure i’m in the moment rather than mentally flicking onto what’s next in my reading pile. At least now i know its the monkey in me to blame. Totally agree that there’s times when escapism is necessary but it’s good at others to engage your brain and confront the uncomfortable.

Samuel Beckett trivia (one for thegue); he’s the only Nobel laureate to have played 1st Class cricket. A game that non fans may find akin to waiting for Godot if forced to contend with an interminable 5 day match time, especially when beset by rain delays.

And on the topic of sport, finally a chance to share this short of Beckett and James Joyce playing golf. It does contain plenty of swearing so be warned. The makers of the Topic bar have missed a trick in not taking up the description of being ‘all fecund in its nuttiness’ in their advertising.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=kbF5hDU_F-U

That was nuttier than gizzards served with giblet soup and liver slices fried with crustcrumbs! For reasons unknown, but time will tell.

Yes, I agree. Very insightful and made me think, which can be a dangerous thing, but a good thing.

Our own constant flitting from one thought to another is one example of our “monkey minds” at work. We’ll never escape it completely, and that’s probably a good thing.

My monkey mind is on steroids. My wife showed me a list of funny quotes the other day and one of them was “Don’t walk a mile in my shoes. That’s boring. Try getting in my head for a half-hour. That will freak you right out” I identified with that immediately.

You hit on something with which we can all likely relate, and that’s the fears and anxieties we try to avoid but ultimately cannot. And it is comforting to see it portrayed as universal, and that I am not alone in the struggle. Most people would rather avoid Waiting For Godot because it forces us to confront what we try to escape, and it’s interesting that the prisoners were cool with it, because for them, it was not as easy to escape those realities. As for me, based on your description of the play, I admittedly would rather watch Waiting For Guffman, given the choice, but you brought to life some really poignant and important thoughts to ponder.

Christopher Guest is always welcome in my house.

But he just can’t bend it like Beckett…

What I know about the play is what I read here today, but it would seem that Guest may have been purposely drawing parallels with it in a roundabout way, not just riffing off the title. I could be wrong.

“ (B)end it like Beckett…”

Can I please ask for a do-over for the line in the teaser graphic? That’s the one! A 10/10, right there!

As editor, you can bend it any way you see fit!

groan

I really, really tried to understand cricket when I lived in England, but, but. Ughhh. I’d be watching and nothing would change, but suddenly everyone in the stands would start cheering. What the heck? Maybe, as an analogy for Godot, it starts to make sense.

Sports? Oh yeah, pure entertainment tickling the monkey brain.

Bit of a coincidence of timing (or is it synchronicity?) but Alan Moore was one of the people I alluded to last post who helped me understand and appreciate the often impenetrable works of Aleister Crowley.

Also, like with Glen or Glenda, I am absolutely convinced that David Lynch is a huge fan of Waiting for Godot. I haven’t yet seen or read anything to confirm this particular hunch, but…it’s pretty obvious, is it not?

This is not a topic I expected to encounter today, but I certainly resonate with it, particularly as I age and it gets more difficult to wiggle out of facing and pondering certain realities regarding mortality. I started reading a book called Small Victories by Anne Lamott and the first parapgraph of the book is

“The worst possible thing you can do when you’re down in the dumps, tweaking, vaporous with victimized self-righteousness, or bored, is to talk a walk with dying friends. They will ruin everything for you.”

Perhaps it’s going down a different path than Waiting for Godot, but ultimately leading to the same place. We’ll see.

Oh, and “This is why we lost the colonies!” just cracked me up. Classic.

Yes, having officially hit middle age, I am pondering those realities as well.

There is also something about Beckett’s writing, particularly his bouts of linguistic entropy–which occur only rarely in Godot but are amplified elsewhere in his ouevre–that really unnerves me. As I said, it made me feel like I was losing my mind. But specifically, it made me question my ability to think and understand coherently. And as such, it exposed some very real fears I have about neural degeneration and dementia.

I think part of my issue is that my life has featured some dramatic shifts that required some heavy adaptation. Learning Japanese took a lot of time and effort, but then I went to grad school and had to master experimental neuroscience. I did lab research for 10 years, but then I shifted to applied research and program evaluation for the government, which is a whole new cluster of approaches, terms, not to mention policies, etc.

While I’ve been fairly successful in my adaptation, a lot rests on it. As such, I do think there’s this underlying fear of just cracking at some point, of breaking down. I was never conscious enough of that fear to voice it until I watched Godot. I can’t say it was a fun experience to watch it, but it was incredibly enriching.

(and yet there really are plenty of funny one liners. My post doesn’t really do justice to the comedic side of the play)

Fear of dementia is right in my wheelhouse.

“This is why we lost the colonies!” amused me too. Could be taken as an affirmation that we were right to lose them if this is the sort of thing they get up to.

But much more likely the knee jerk reaction of someone shocked out of their comfortable existence and being confronted with actual ideas that require some thought. If we encourage people to think there’s no telling what that will lead to is the inference. You give them self governance and they think they own the place!

I once saw a short film called Wavelength. It’s a single shot of a room. Over the course of its 45 minutes, it very, very slowly zoomed in from a wide angle of the room to a picture of waves on the far wall. At one point, workers brought in a desk and set it against a wall. Later, someone came in and fell dead. Even later, when the camera had zoomed in too far to see the people, someone can be heard discovering the body. Aside from those three bits of action, nothing happened.

It’s an interesting film in retrospect. At the time though, it was frustrating. I’m glad I saw it because it gave me something to think about the way Godot gives you something to think about. And I got this story out of it.

Monkey see, monkey wait.

Just found a description of Wavelength on Wikipedia, and it’s a little different than I remember, but it’s been 47 years since I’ve seen it, so I forgive myself.

It sounds right up my alley.

The description actually reminds me of the film Five (Dedicated to Ozu) by the Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami.

Again, no plot as such. Just five long shots of bodies of water. But watching it changes how you watch. I began to see the scenes more as moving paintings than as narratives. Though the dance of the driftwood in the ocean tides made for some compelling drama!

But only if you’re on the right wavelength.

I’ll have to give that one a try.

Of course you can see the play, but why not live the experience yourself through the Waiting for Godot video game?

Damn. It’s not an original idea. I googled Waiting for Godot and Gilligan’s Island. Lots of people see it, even creator Sherwood Schwartz. One episode is called Waiting for Watubi. Cast Away is a better example. It turns into Waiting for Godot when Tom Hanks invents Wilson.

This was a fun read.

Waiting for Godot is a comedy. Googled Godot and Seinfeld.

Yup.

Maybe The Caucasian Chalk Circle better fits the miserablist label.

Number of laughs in Dogville: Zero.

The playing of “Young Americans” at the end of Dogville got a dark chuckle from me.

Sarah Silverman induced many dark chuckles from me. She performed a terrifying(but hilarious) monologue on Bill Maher pre-2015. Can’t find it. I presume ironical distance. I’ll never forget Maher’s other guest gesticulating rather wildly after Silverman’s set was over. I hear echoes of her themes in political discourse sans ironical distance. She had a knack of finding humor in anything. But, in retrospect, maybe there were people who never found any of it funny.

This is why she’s on TBS hosting Stupid Pet Tricks.

Sorry. To get back on topic. I’m about thirty-five pages into Waiting for Godot. It’s been awhile. It’s part of my garage collection. (I’d be thrilled if somebody stole a book. That’s the world I want to live in. It never happened.) I can feel my heart accelerating. The play is landing differently. Yikes. I get it.